Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

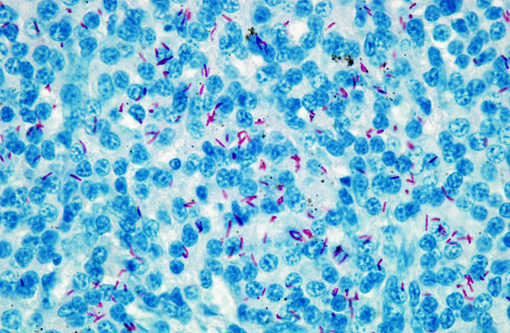

In Xenopus tropicalis, M. szulgai and M.liflandii have been described as a systemic disease and M.gordonae as a disease of the integument until now.(3,11,5,12) M.gordonae is considered as an occasional human pathogen, especially in immunocompromised patients.(1,9) It has been associated with granulomatous skin lesions or with disseminated lesions.(1,9)

In our case, Mycobacterium gordonae has been isolated from internal organs (spleen and liver) and therefore associated with a systemic disease.

The source of the infection has not yet been identified.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

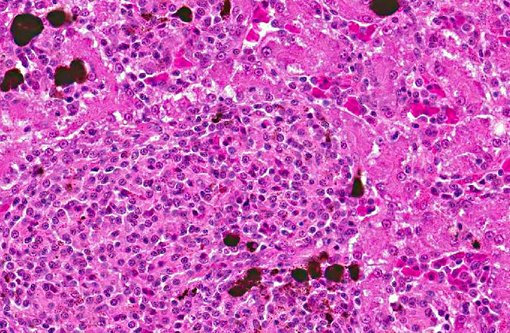

Participants also discussed the role of melanomacrophages in amphibians. Amphibians, like reptiles and fish, have aggregates of phagocytic macrophages within several organs (liver, spleen, and kidney of fish; liver and spleen of amphibians and reptiles).(7) Systemic inflammation can cause these macrophages to proliferate and develop aggregates in other organs as well, such as the atrium of fish. Macrophages within these aggregates often contain melanin granules, as well as hemosiderin and lipofuscin. While melanomacrophage aggregates are sometimes considered metabolic dumps, the melanin granules are thought to play a role in the production of free radicals and microbial killing.(8,13) In fish, melanomacrophage aggregates have been shown to function as primitive analogues to lymphoid germinal centers, trapping antigens and immune complexes. In higher fish, amphibians and reptiles, melanomacrophage aggregates may have a capsule.(13)

Lastly, participants noted the presence of few hepatocytes with eosinophilic intracytoplasmic vacuoles. These were likened to the postmortem vacuoles described in mice that result from plasma influx into the cytoplasm, as such, they were considered clinically insignificant to this case.(7)

References:

2. Beran V, Matlova L, Dvorska L, Svastova P, Pavlik I. Distribution of mycobacteria in clinically healthy ornamental fish and their aquarium environment. J Fish Dis. 2006;29:383-93.

3. Chai N, Deforges L, Sougakoff W, Truffot-Pernot C, De Luze A, Demeneix B. Mycobacterium sulzgai infection in a captive population of African clawed frogs (Xenopus tropicalis). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2006;37:55-58.

4. Ferreira R, Fonseca L, Alfonso A, Da Silva M, Saad M, Lilenbaum W. A report of mycobacteriosis caused by Mycobacterium marinum in bullfrogs (Rana catasbeiana). Vet J. 2004;171:177-180.

5. Fremont-Rahl JJ, Ek C, Williamson HR, Small PLC, Fox JG, Muthupalani S. Mycobacterium liflandii outbreak in a research colony of Xenopus (Silurana) tropicalis frogs. Vet Pathol. 2011;48:856-867.

6. Green S, Lifland B, Bouley D, Brown B, Wallace R, Ferrel J. Disease attributed to Mycobacterium chelonae in South African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis). Comp Med. 2000;50:675-679.

7. Li X, Elwell MR, Ryan AM, Ochoa R. Morphogenesis of postmortem hepatocyte vacuolation and liver weight increases in Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicologic Pathology. 2003;31:682688.

8. Roberts RJ. Fish Pathology. 3rd ed. New York: WB Saunders; 2001:30-31.Â

9. Rusconi S, Gori A, Vago L, Marchetti G, Franzetti F. Cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium gordonae in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient receiving antimycobacterial treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1490-1.Â

10. Schwabacher H. A strain of mycobacterium isolated from skin lesions of a cold-blooded animal, Xenopus laevis, and its relation to atypical acid-fast bacilli occurring in man. J Hyg (Lond). 1959;57:57-67.

11. Sanchez-Morgado J, Gallagher A, Johnson L. Mycobacterium gordonae in a colony of African clawed frogs (Xenopus tropicalis). Lab Anim. 2009;43:300-303.

12. Suykerbuyk P, Vleminckx K, Pasmans F, Stragier P, Ablordey A, Tran H, et al. Mycobacterium liflandii infection in European colony of Silurana tropicalis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:743-746.

13. Terio KA. Comparative Inflammatory Responses of Non-Mammalian Vertebrates: Robbins and Cotran for the Birds. In: ACVP and ASVCP, eds. 55th Annual Meeting of the American College of Veterinary Pathologists (ACVP) & 39th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Pathology (ASVCP). Middleton WI: American College of Veterinary Pathologists & American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology. Internet Publisher: Ithaca, New York: International Veterinary Information Service. http://www.ivis.org/proceedings/ACVP/2004/Terio/IVIS.pdf Accessed online 1 February 2013.Â