Signalment:

Gross Description:

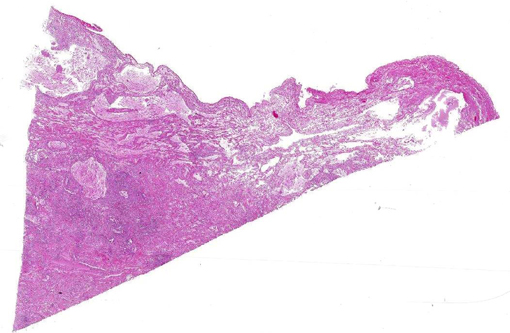

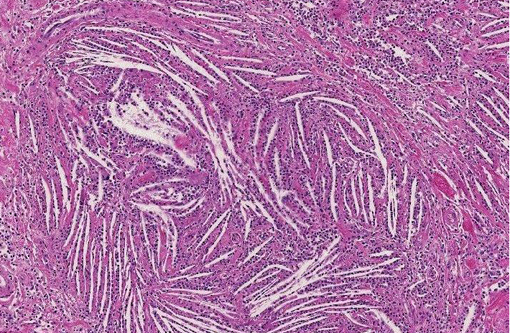

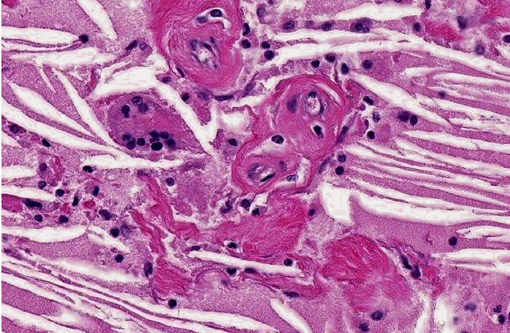

Histopathologic Description:

Changes in cerebral cortical tissue (slides not included) surrounding the dilated lateral ventricles included rarefaction and loss of nerve cell bodies immediately peripheral to the lateral ventricle space. In a number of sections, there was complete loss of the nerve cell body layer and neuropil collapse resulting in an appearance of increased blood vessels somewhat like a line of irregular granulation tissue. Random areas of spongy degeneration were noted in cortical white matter about the dilated ventricles. Additionally, the meninges sometimes contained a few inflammatory cells, predominately histiocytes, lymphocytes, and/or neutrophils.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Knowing the above chain of events is likely in many cases, then, the veterinary pathologist should preface the undertaking of an equine neurological case necropsy, with a set of all possible differential diagnoses, in addition to any previous clinical diagnosis. Many equine neurological cases, and particularly CNS cases, have overlap of signs. Even if a case has a diagnosis confirmed by reliable clinical testing, as in this case, that particular diagnosis may not be the cause of the recent chain of events that brought about the euthanasia of the horse. Finally, there are some equine neurological cases that may be a rule out diagnosis. Botulism is one disease that always should come to mind as an example of this. Because the levels of botulinum toxin required to affect and even kill a horse are so low that current modes of testing may be unable to detect, the pathologist should always have a conversation with the horse owner and clinical veterinarian, about any and all of the details of environment and husbandry that could possibly lead to a final rule-out diagnosis of botulism.

Clearly then, cholesterol granulomas should be considered as a differential diagnosis in any equine neurological case, especially those in older horses with predominantly CNS signs. In fact, it has been reported that 15-20% of old horses have cholesterol granulomas, although many may be present in the absence of clinical signs.

Cholesterol granulomas and cholesteatoma have been used in veterinary literature to describe the lesion diagnosed in this case.(2,3,4,6,7) There is some disagreement of sorts as to whether cholesteatoma should be used to describe this brain lesion, specifically found in old horses.(2) Cholesteatoma is a term also used to describe a nodular mass in the middle ear, although this aural cholesteatoma has not been reported in horses.(5) It may be a prudent move to restrict the use of cholesterol granulomas only to describe this specific entity of aged horses, rather than use cholesteatoma interchangeably with cholesterol granuloma.

Despite this sort of disagreement of terminology for equine cholesterol granulomas, the mechanism of development is basically agreed upon.(2,3,4,6,7) The exact underlying pathogenesis, however, seems to be uncertain.(7) Equine cholesterol granulomas are often described as an aging or degenerative phenomenon.(2,3,5,7) Repeated episodes of hemorrhage and/or chronic intermittent congestion, edema and congestive hemorrhage in the choroid plexuses are believed to be the pathological processes responsible for development of cholesterol granulomas of older horses.(2,3) Erythrocytes are likely the source of the cholesterol.(6) It is when hemorrhage results in formation of a hematoma, subsequently becoming organized, followed by breakdown of red blood cells to release cholesterol that the granuloma develops.(2) Cholesterol accumulation, both extracellular and within macrophages, is observed and the cholesterol itself stimulates a foreign body response or giant cell reaction,(6) resulting in developing and progressive granulomatous inflammation and fibrovascular organization.(2,3,4,6,7) Whether this is or can result from a single event or requires multiple episodes is speculative, but likely the larger cholesterol granulomas develop because of multiple events of this type.

Small cholesterol granulomas may remain clinically silent and are discovered incidentally. The larger cholesterol granulomas produce clinical CNS signs and signs can be variable and progressive. Most, if not all, of the effects of large cholesterol granulomas are caused by blockage of interventricular foramen resulting in development of internal hydrocephalus and progressive degeneration and compression atrophy of the cerebral hemispheres. Inflammation in the brain itself is usually minimal and represented as small infiltrates of macrophage, lymphocytes, and neutrophils in the meninges. It may be fortunate that even though the occurrence of cholesterol granulomas in old horses is reported to be 15-20%, the majority are found in the fourth ventricle; and, development of hydrocephalus, the usual cause of clinical signs, is limited to those in the lateral ventricles that can by location block the interventricular formen causing hydrocephalus.(3)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW. The nervous system. In: Veterinary Pathology. 6th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997:1286, 1291-2.

3. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2007:345-6.

4. McGavin DM, Zachary JF. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:47, 922.

5. McGavin, Carlton & Zachary. The nervous system. In: Thomsons Special Veterinary Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2001:448-449.

6. Moulton JE. Tumors in Domestic Animals, 3rd ed. Berekley, CA: University of California Press, 1990:647.

7. Summers B, Cummings J, de Lahunta A. Neuropathology of aging. In: Veterinary Neuropathology. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1995:49-53.