Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 15

22 January 2020

Dr. Cory

Brayton, DVM, PhD, DACVP, DACLAM,

Director, Phenotypic Core

Associate Professor of Molecular and Comparative and Pathobiology

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

733 N. Broadway

Baltimore MD, 21205

CASE II: MS18-3968 (JPC 4136806).

Signalment: Adult, male, albino, CYBB[ko] mouse, Mus musculus

History: NSG.Cybb[KO] mouse observed with scruffy hair coat, slightly hunched posture and pale ears. Mice of this strain have been spontaneously dying. These mice are on corn cob bedding and are provided with TMS antibiotic water. The feed is regular rodent chow and is autoclaved with the cage setup. The antibiotic water is made by sterilizing tap water in the autoclave and then adding TMS at the room in a Biological Safety Cabinet (BSC). The cages are sterile when they arrive at the room with aseptic technique used to transfer the mice from the dirty cage to the clean cage. All manipulation is performed in a BSC.

Gross Pathology: Presented for necropsy was a live adult male white mouse. The animal appeared to be in good nutritional condition. The animal had a roughened hair coat, yet was alert and active in the transport box. The animal was euthanized with CO2.

Upon opening the carcass, adequate adipose stores were observed. The subcutis was slightly tacky indicating mild dehydration. Upon opening the peritoneal cavity, the spleen was enlarged approximately three times normal size and contained multifocal to coalescing pale tan masses that expanded above the capsular surface. The liver was also enlarged approximately three times normal size with multifocal to coalescing pale tan slightly raised masses scattered throughout.

Upon opening the pleural cavity, the lungs contained numerous light red pinpoint scattered foci. There was a 1 mm in diameter clear cyst in the right caudal lung lobe.

Lesions were not observed in the brain, heart, kidneys, pancreas, the entire male reproductive tract, and the entire gastrointestinal tract that has scant ingesta/digesta throughout and multiple formed feces in the descending colon.

Laboratory results: Microbiology yielded Candida parapsilosis from the liver.

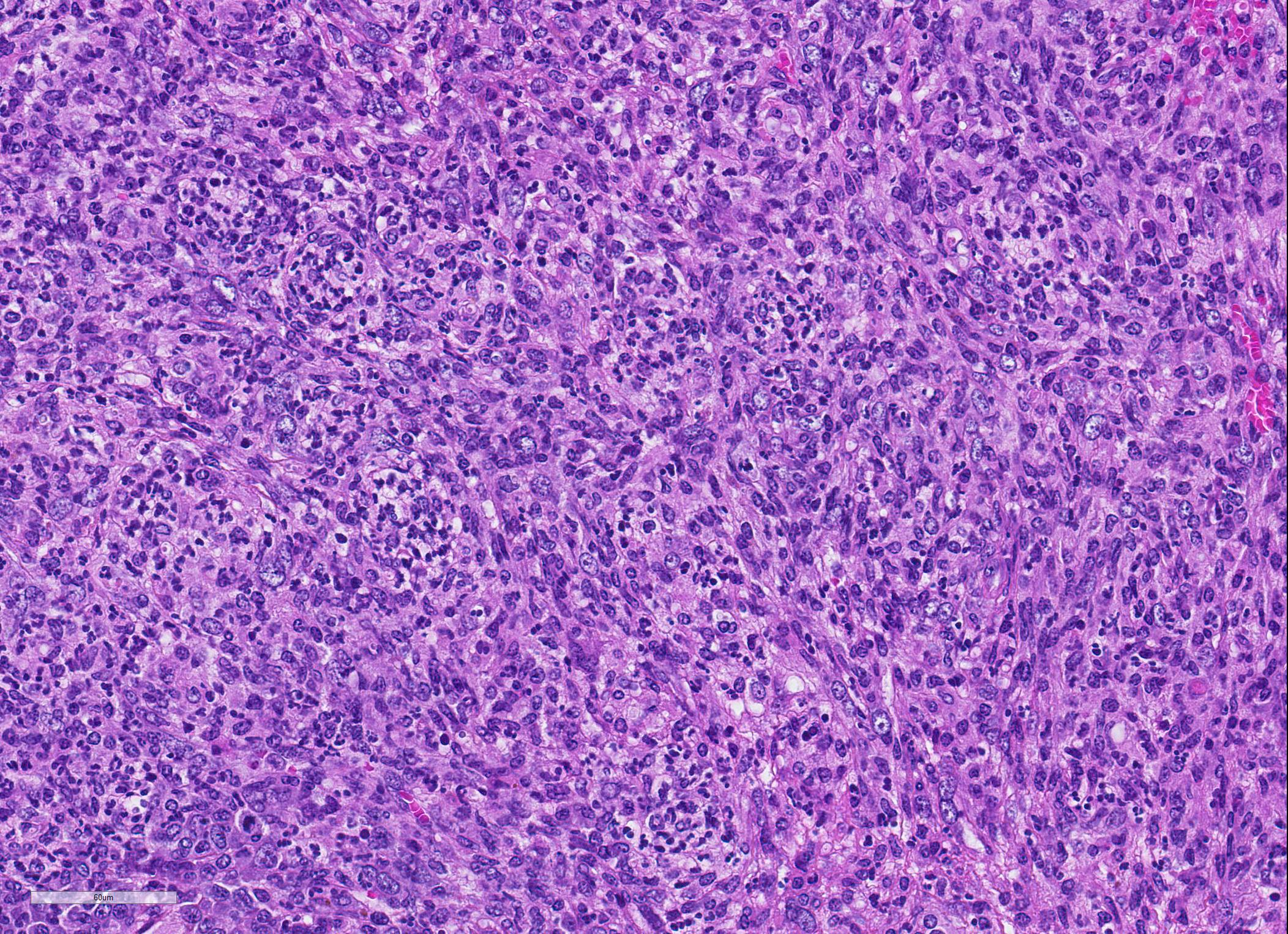

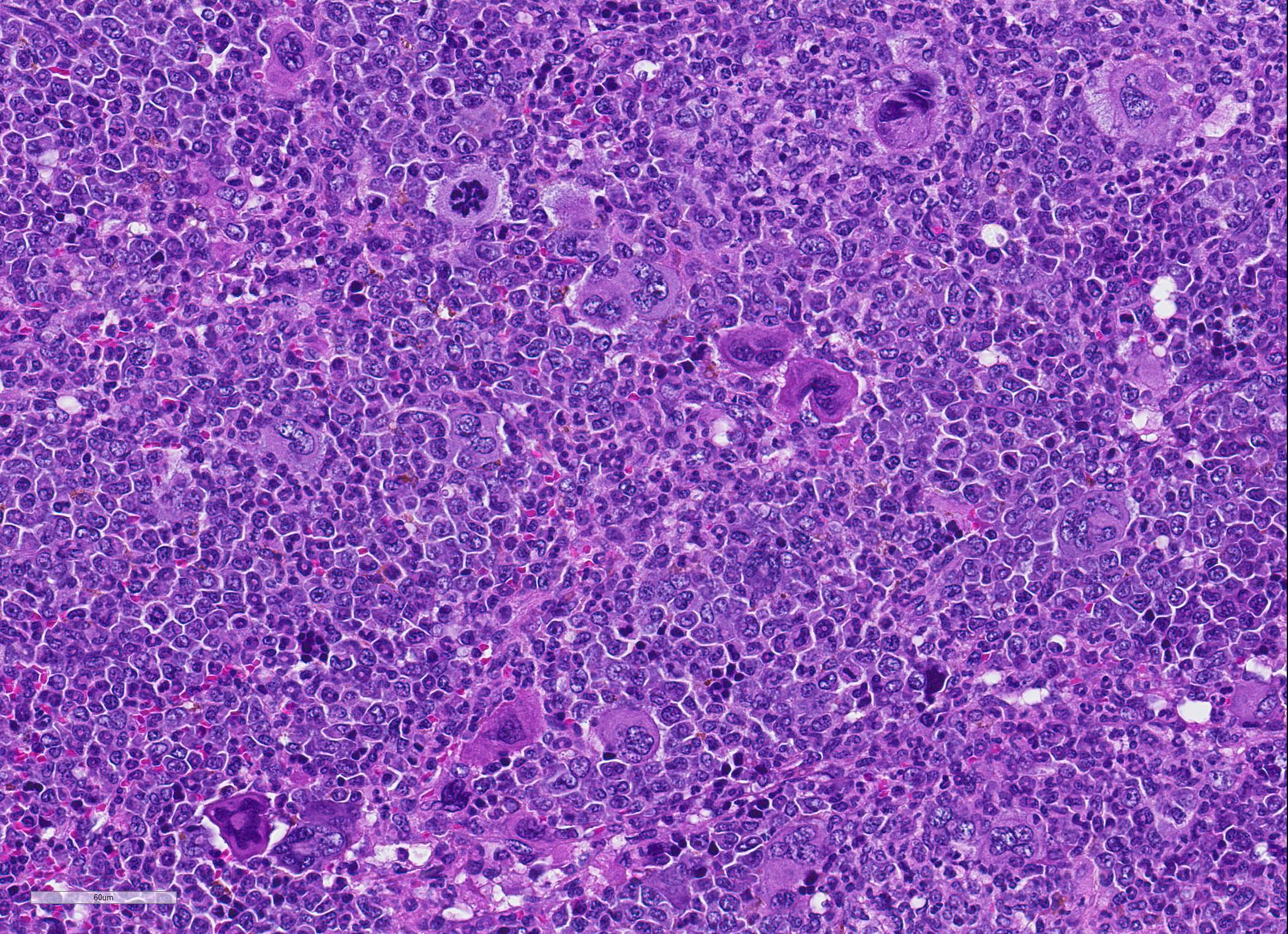

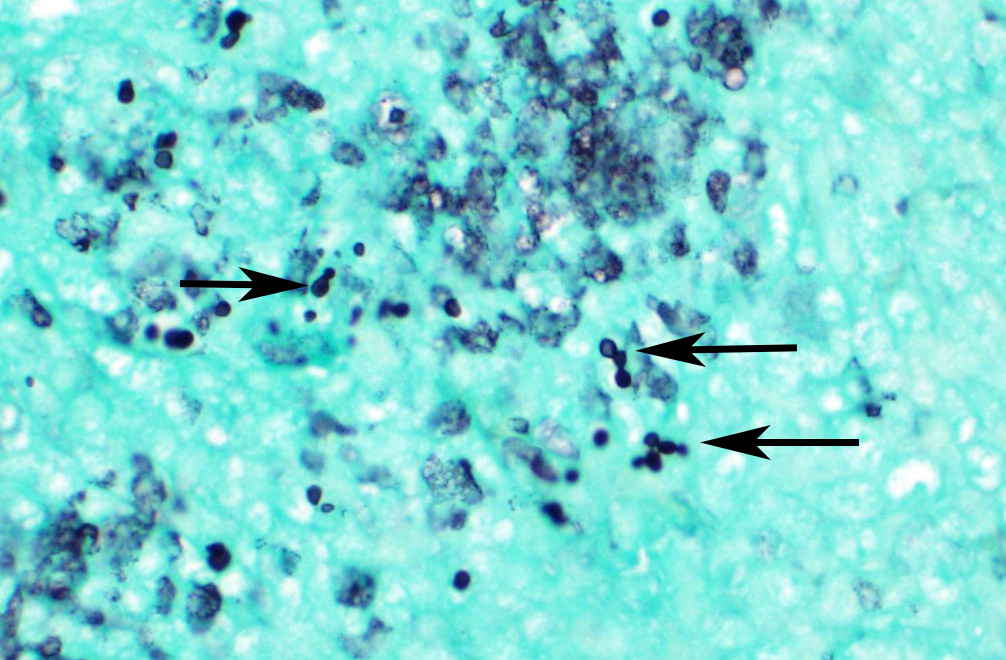

Microscopic Description: Spleen ? Multifocal to coalescing granulomas with epithelioid macrophages, many with neutrophils, and a coarse fibrous connective tissue network are observed. In a number of these are intracellular, one to a few, 1-5 um round to oval yeast organisms with a clear halo, and which a number are seen budding on PAS stain. The adjacent parenchyma has a moderate granulocytic hyperplasia. Similar lesions were observed in the liver, and yeast were observed in the liver, kidneys (tubulitis) and lungs (alveolitis).

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Spleen, splenitis, pyogranulomatous and fibrosing, multifocal to coalescing, severe, chronic with intralesional yeast, Candida parapsilosis

Contributor Comment: NSG.Cybb{KO} mice are a genetically altered mouse strain that is severely immunocompromised. NSG (NOD.Cg-Prkdscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) is a lymphocyte deficient strain, and Cybb KO (CYBB gene is located on X-chromosome, and encodes the gp91phox protein) is the most common form of Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD).12 CGD is an immunodeficiency with a defect in phagocytes (macrophages, neutrophils) to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) which are needed for microbicidal activity. Normally, ROS are generated by phagocyte NADPH oxidase. This enzyme is composed of 5 subunits; 2 plasma membranes and 3 cytosolic. Membrane bound are transmembrane glycoproteins (gp), one with 91kD mass called gp91phox (phox for phagocyte oxidase; also known as NOX2[neutrophil oxidase-2]) and a 22kD gp called p22phox. These two form a heterodimer. The 3 cytosolic subunits (p40phox, p47phox, p67phox) form a heterotrimer. The genes of the five components are CYBB [cytochrome b beta] located on the X-chromosome encoding gp91phox, CYBA [cytochrome b alpha]encoding p22phox, NCF1[neutrophil cytosol factor] encoding p47phox, NCF2 encoding p67phox, and NCF4 encoding p40phox.10

The most common form of CGD involves the CYBB gene (deletion, frameshift, nonsense, missense, splice site mutation) that affects mostly males because of the predominant mode of genetic transmission (X- chromosome).8 Interestingly, heterozygous mothers of affected males will carry a proportion of innate immune cells that are fully oxidase deficient. These individuals are prone to both infectious complications and autoimmune diseases. Of note, the risk of developing autoimmune disease was not at all related to degree of residual oxidase activity as it is in developing an infection. This suggests that even the presence of a minority of cells with absent oxidase activity predisposes to a dysregulated immune response in a dominant form.12

CGD appears to be a dysregulated granulomatous inflammation in various organs including the GI tract, respiratory tract, as well as the eye and urinary tract. In some patients a true autoimmune disease was exhibited; systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, Sjogren?s syndrome and atopic dermatitis. Interestingly, a large percentage of human patients did not show any evidence of infection.13

Some patients with CGD suffer from a variety of recurrent bacterial and fungal diseases. The most common bacterial infections include Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella spp., Burkholderia cepacia, Serratia marcescens and Salmonella spp.9,14 Fungal infections include Aspergillus fumigatus, A. nidulans, A. niger, A. flavus, Zygomycota (primarily Rhizopus spp.), Candida spp., Trichosporon spp., Paecilomyces spp., Scedosporium spp., Penicillium spp., Acremonium spp., Alternaria spp., Inonotus spp., Exophiala, Chrysosporium spp., Fusarium spp., Microascus spp., and Hansela spp.7,15 A. nidulans seems to have a unique interaction with CGD hosts.7 Geosmithia argillacea has recently been shown to be mistakenly identified as Paecilomyces spp. in the past.6 Dimorphic yeast form infections are exceedingly rare with only one reported case each of Coccidioides immitis,14 Histoplasma capsulatum,14 and Sporothrix schenckii.14

In this case Candida parapsilosis was the pathogenic yeast identified. Candida species are mainly found in the gastrointestinal tract of humans9. C. parapsilosis is found frequently on the skin and hands11. Although commensal, they can become pathogenic when host defense mechanisms or anatomical barriers are compromised.10 C. parapsilosis is currently the second leading cause of candidemia which is associated with a high morbidity and mortality rate in humans.12 In CGD humans, Candida species were isolated from meningitis, fungemia, lymphadenitis.13

C. parapsilosis is actually a complex of 3 distinct genetic species: C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis.2,10 Polymorphisms in the genes COX3 (mitochondrial gene cytochrome oxidase subunit 3), SADH (secondary alcohol dehydrogenase) and SYA1 (putative alanyl-tRNA synthetase) distinguish the three species.5 Virulence of C. parapsilosis is related to factors such as cell wall constituents, adhesion to biotic and abiotic structures leading to biofilm formation, and extracellular enzymes such as aspartic proteases, phospholipases and lipases. Aspartic proteases promote tissue colonization and invasion by rupturing host mucosal membranes. They may also aid in dispersion of biofilms. Phospholipases promote rupture of host cell membranes. Lipases help with acquiring nutrition, support fungal growth, mediate adhesion to cells and tissues, and coordinate yeast interactions with enzymes and immune cells during the infectious process.11

Initial attachment of Candida to host cells is followed by cell division, proliferation (forming yeast and pseudohyphae) and subsequent biofilm formation. Biofilm formation is an important virulence factor as it confers significant resistance to antifungal therapy by limiting the penetration of substances through the matrix (water, ions, carbohydrates, proteins and nucleic acids) and protecting fungal cells from host immune responses14. Morphologically, C. parapsilosis is unable to form true hyphae, but forming pseudohyphae is associated with virulence.11

This case is somewhat baffling given that the animal was in a sterile environment with sterile bedding, caging and water yet still was exposed to Candida. However, in humans, C. parapsilosis is frequently isolated from hands and from sterile body sites. Thus, human transmission may have been possible. Overall, three mice developed similar lesions, with two having recognizable yeast organisms on histopathology. One should be vigilant and be alert for uncommon infections in a laboratory setting.

Contributing Institution:

Division of Veterinary Resources

National Institute of Health

9000 Rockville Pike

Bldg. 28A, room 107

Bethesda, MD20892

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Spleen: Splenitis, pyogranulomatous, diffuse, severe, with intrahistiocytic yeasts. 2. Spleen, red pulp: Extramedullary hematopoiesis, diffuse, severe.

JPC

Comment: The

contributor has provided an excellent review of this animal model of an

uncommon inherited primary immunodeficiency, the mechanism of the

immunodeficiency, as well as a review of Candida sp. in general as well as C.

parasilopsis, the particular pathogen in this case.

As mentioned by the contributor, chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is an

uncommon X-linked immunodeficiency in humans resulting in frequent bacterial

and fiungal infections. Patients with CGD may possess a defect in one of four

different structural proteins in NADPH oxidase.8,10 NADPH oxidase

catalyzes the transfer of a single electron from NADPH to molecular oxygen,

generating one of four reactive oxygen species, from the superoxide radical,

including the peroxynitrite anion, hydroxyl anion, hypochlorous acid, and nitryl

chloride. 8,10

The contributor mentions the many types of fungal infection which are seen in immunsuppressed individuals. The reason for this is that mononuclear phagocyte activity is the major driver of resistance to systemic mycoses. Patients suffering from systemic mycosis have shown consistent benefit from concurrent administration of macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Patients with CGD are treated with continuous antibacterial and antifungal medications, and the only current long-term treatment is allogeneic hematopoitic stem cell transplants.

Interestingly,

this WSC conference submission is not the JPC?s first encounter with this

mutant strain of mouse from the National Institutes of Health, Following a

rotation at the Dept. of Veterinary Resources at the NIH, then resident Dr.

Shannon Lacy (himself a former resident coodinator of the Wednesday Slide

Conference published an article about infection seen in this same strain of

knockout mice with another saprophytic fungus, Trichosporoon beigelli.8

Like Candida, Trichosporoon is part of the normal flora of human

skin and GI tract. This was the first report of disseminated trichosporoonosis

in the laboratory mice of any immunosuppressed strain.8

The moderator noted that in this case, the yeasts in the submitted slide did

not make either pseudohyphae or hyphae, which is consistent with the

literature. C. parapsilosis apparently makes pseudohyphae in culture

and within biofilms and not in tissue. It also does not produce true hyphae.

References:

1. Antachopoulos C. Invasive fungal infections in congenital immunodeficiencies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010; 16:1335-1342.

2. Bertini A, De Bernardis F, Hensgens LAM, Sandini S, Senesi S, Tavanti A. Comparison of Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis adhesive properties and pathogenicity. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013; 303:98-103.

3. Bonassoli LA, Bertoli M, Scidzinski TIE. High frequency of Candida parapsilosis on the hands of healthy hosts. J Hosp Infect. 2005; 59:159-162.

4. Cavalheiro M, Cacho Teixeira M. Candida biofilms: Threats, challenges, and promising strategies. Frontiers Med 2018; 5:1-15.

5. De Aguiar Cordeiro R, Alencar S, de Souza Collares Maia Castelo-Branco, et al. Candida parapsilosis complex in veterinary medicine: A historical overview, biology, virulence attributes and antifungal susceptibility traits. Vet Microbiol. 2017; 212:22-30.

6. DeRavin SS, Challipalli M, Anderson V, Shea YR, Marciano B, Hilligross D, Marquesen M, DeCastro R, et al. Geosmithia argillacea: An emerging cause of invasive mycosis in human chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 52(6):e136-e143.

7. Henriet S, Verweij PE, Holland SM, Warris A. Invasive fungal infections in patients with chronic granulomatous disease. In: Curtis N, et al. eds. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Hot topics in infection and immunity in children IX. New York, NY; Springer Science;2013: 27-55.

8. Lacy SH, Gardiner DJ, Olson LC, Ding L, Holland SM, Bryant MA. Disseminated trichosporonosis in a murine model of chronic granulomatous disase. Comp Med 2003; 53(3): 303-308.

9. Rider NL, Jameson MB, Creech CB. Chronic granulomatous disease: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and genetic basis of disease. JPIDS. 2018; 7(S1):S2-S5.

10. Roos D. Chronic granulomatous disease. Br Med Bull. 2016; 118:53-66.

11. Silva S, Negri M, Henriques M, Oliveira R, Williams DW, Azeredo J. Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida tropicalis:biology, epidemiology, pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2012; 36:288-305.

12. Sweeney CL, Choi U, Liu C, Koontz S, Ha S_K, Malech HL. CRISPR-mediated knockout of Cybb in NSG mice establishes a model of chronic granulomatous disease for human stem-cell gene therapy transplants. Hum Gene Therap. 2017; 28(7):565-575.

13. Thomas DC. How the phagocyte NADPH oxidase regulates innate immunity. Free Rad Bio Med. 2018; 125:44-52.

14. Trotter JR, Sriaroon P, Berman D, Petrovic A, Leiding JW. Sporothrix schenckii lymphadenitis in a male with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease. J Clin Immunol. 2014; 34:49-52.

15. Winkelstein JA, Marino MC, Johnston RB, Boyle J, Curnette J, Gallin JI, Malech HL, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease. Report on a national registry of 268 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000; 79(3):155-169.