Signalment:

Gross Description:

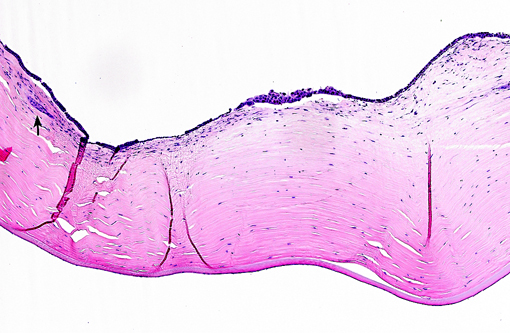

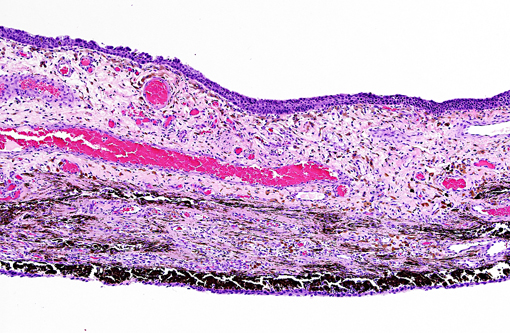

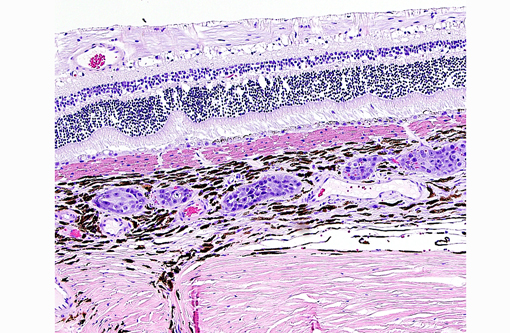

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Eye, Metastatic carcinoma.

2. Cornea, severe and diffuse ulcerative and collagenolytic keratitis with axial facet lesion formation.

3. Retina, Marked and diffuse ganglion cell layer atrophy.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Table 1. Cases of feline metastatic tumor to the eye on the COPLOW database

| Cases | % | |||

| Feline ocular tumors (total) | 4,542 | |||

| Feline metastatic tumors to the eye | 580 | 12% of total cases | ||

| 1. Lymphomas | 423 | 72% of metastatic cases | ||

| 1. Non-lymphoma | 157 | 28% of metastatic cases | ||

| a. Undifferentiated neoplasia | 05 | 3.1% of non-lymphomas | ||

| a. Sarcoma | 25 | 15.9% of non-lymphomas | ||

| a. Carcinoma | 127 | 81% of non-lymphomas | ||

| - Undifferentiated carcinoma | 74 | 58.2% of carcinomas | ||

| - Pulmonary carcinoma | 24 | 18.8% of carcinomas | ||

| - Squamous cell carcinoma | 24 | 18.8% of carcinomas | ||

| - Mammary carcinoma | 03 | 2.3% of carcinomas | ||

| - Anal sac adenocarcinoma | 01 | 0.7% of carcinomas | ||

| - Uterine carcinoma | 01 | 0.7% of carcinomas | ||

Common morphologic features of metastatic neoplasia in cat eyes include(1):

- Uni- or bilateral uveal metastases.

- A tendency to affect the choroid more often than the anterior uvea.

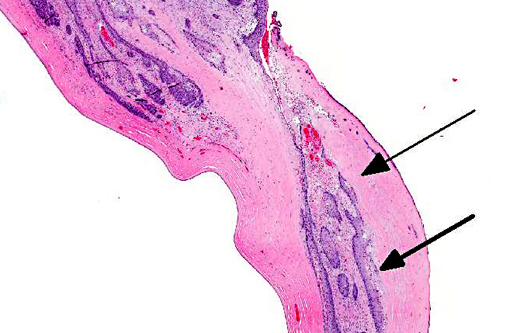

- When the anterior uvea is affected, neoplastic cells line or carpet the surfaces of the iris and ciliary body.

- Extensive and widespread invasion of blood vessels.Â

- A pattern of choroidal infarction with characteristic, wedge-shaped areas of tapetal discoloration and profound vascular attenuation visible on funduscopy.

- Orbital involvement may accompany involvement of the posterior segment of the globe.Â

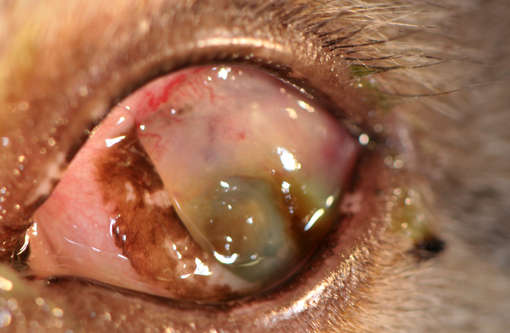

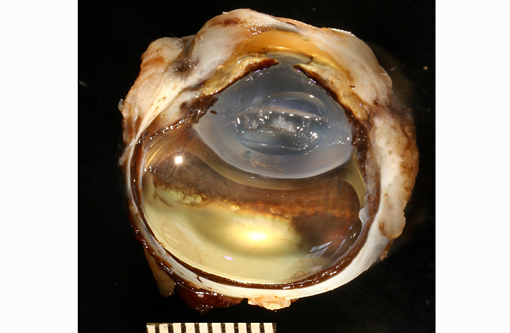

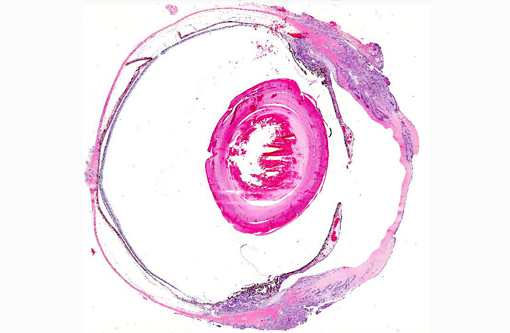

The present case shows most of the previously described common morphologic features of metastatic neoplasia. Of those features, the lining of ocular surfaces and the marked vascular invasion especially of the choroidal vessels are the most salient. Interestingly, the neoplastic cells also produce an unusual pattern of carpeting by proliferating over the ulcerated corneal surface, mimicking the corneal epithelium. The absence of the native corneal epithelium and subsequent exposure of the corneal stroma might have facilitated/stimulated neoplastic cells to proliferate in that pattern.Â

The neoplastic tissue presents classic epithelial morphology with multiple areas developing keratinization of the inner cellular layers. This feature points towards a squamous cell carcinoma, but other undifferentiated carcinomas with squamous metaplasia cannot be ruled out.

Other possible differential diagnoses include pulmonary carcinomas, primary corneo-conjunctival squamous cell carcinomas and mammary carcinomas. Metastatic pulmonary carcinomas tend to form acinar/glandular structures on the uveal tissue and/or present ciliated epithelium carpeting the ocular surfaces. Primary ocular squamous cell carcinomas in cats can invade the intraocular structures, especially the anterior chamber and uvea, but they seldom infiltrate vessels and the posterior aspect of the globe.(4) Metastatic mammary carcinoma is a remote possibility since the cat in this case is male and neutered.

The decrease number of ganglion cells in the retina confirms the clinical diagnosis of secondary glaucoma. In cats, the main histologic feature of glaucoma is loss of ganglion cells without progressive degeneration of the outer retina, as seen in dogs.(1) The majority of glaucomas in cats are secondary to other ocular diseases, most notably chronic lymphoplasmacytic anterior uveitis, systemic hypertension-related intraocular hemorrhages, and intraocular neoplasia.(1,2)

The patient in the present case was lost to follow-up before the identification of a primary tumor.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Many conference participants tentatively identified this tumor as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Ocular involvement of SCC is most common in cattle and horses, but has also been reported in cats and dogs. In all domestic species, SCC involving the ocular surface appears to have a preference for the limbus (corneoscleral junction) which is the transition zone between the corneal and conjunctival epithelial cell populations. The limbus is home to the local stem cell population; stem cells have a high proliferative capacity, are susceptible to the accumulation of oncogenic mutations, and are thought to be the source of many neoplasms. Corneolimbal SCC refers specifically to a neoplasm originating at the limbus with extension into the cornea (as opposed to originating from the corneal epithelium itself).(4) This neoplasm manifests several histologic features suggestive of corneolimbal SCC: neoplastic cells are most numerous in the sclera, ciliary body and limbus, there is fairly prominent intracellular bridging with moderate desmoplasia and there is scattered infiltration of neutrophils; however, participants did not appreciate significant dyskeratosis or formation of keratin pearls, so we are unable to definitively diagnose ocular SCC. The contributor provides a brief, but thorough differential diagnosis for the gross and microscopic lesions in this case.

References:

1. Dubielzig RR, Ketring KL, McLellan GJ, et al. Veterinary Ocular Pathology: a Comparative Review. London: Elsevier; 2010.

2. Grahn BH, Peiffer RL. Fundamentals of veterinary ophthalmic pathology. In: Gelatt KN, ed. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 4th ed. Victoria: Blackwell Publishing, 2007:411-502.

3. Wilcock BP. The eye and ear. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007:459552.

4. Scurell EJ, Lewin G, Solomons M, et al. Corneolimbal squamous cell carcinoma with intraocular invasion in two cats. Vet Ophthalmol. 2013 Feb 20. doi: 10.1111/vop.12036. [Epub ahead of print]