Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 7

23 October 2019

Dr. Dalen Agnew, DVM,

PhD, DACVP

|Associate Professor

Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation

Michigan State University

College of Veterinary Medicine

East Lansing, Michigan

CASE II: 15-1137 (JPC 4066220).

Signalment: Three late term dairy goat fetuses (breed not specified)

History: Multiple late term abortions occurred in a large dairy goat herd. Submitted samples included fixed tissues, tissue pools, abomasal fluid and serum from one of the aborting dams.

Gross Pathology: The submitting veterinarian reported that the placentas had hemorrhages and pinpoint white foci on the cotyledons. Fetal spleens and livers were enlarged.

Laboratory results: Placentas were positive for Chlamydophila by antigen ELISA. PCR for Toxoplasma gondii was negative on placenta and brain. No Campylobacter was isolated and PCR for BVD was negative. FA for Leptospira was negative. A single dam serum was positive for antibodies to Coxiella but negative for Brucella abortus, BVDV and Toxoplasma. Immunohistochemistry for Coxiella burnetii on the placenta was positive.

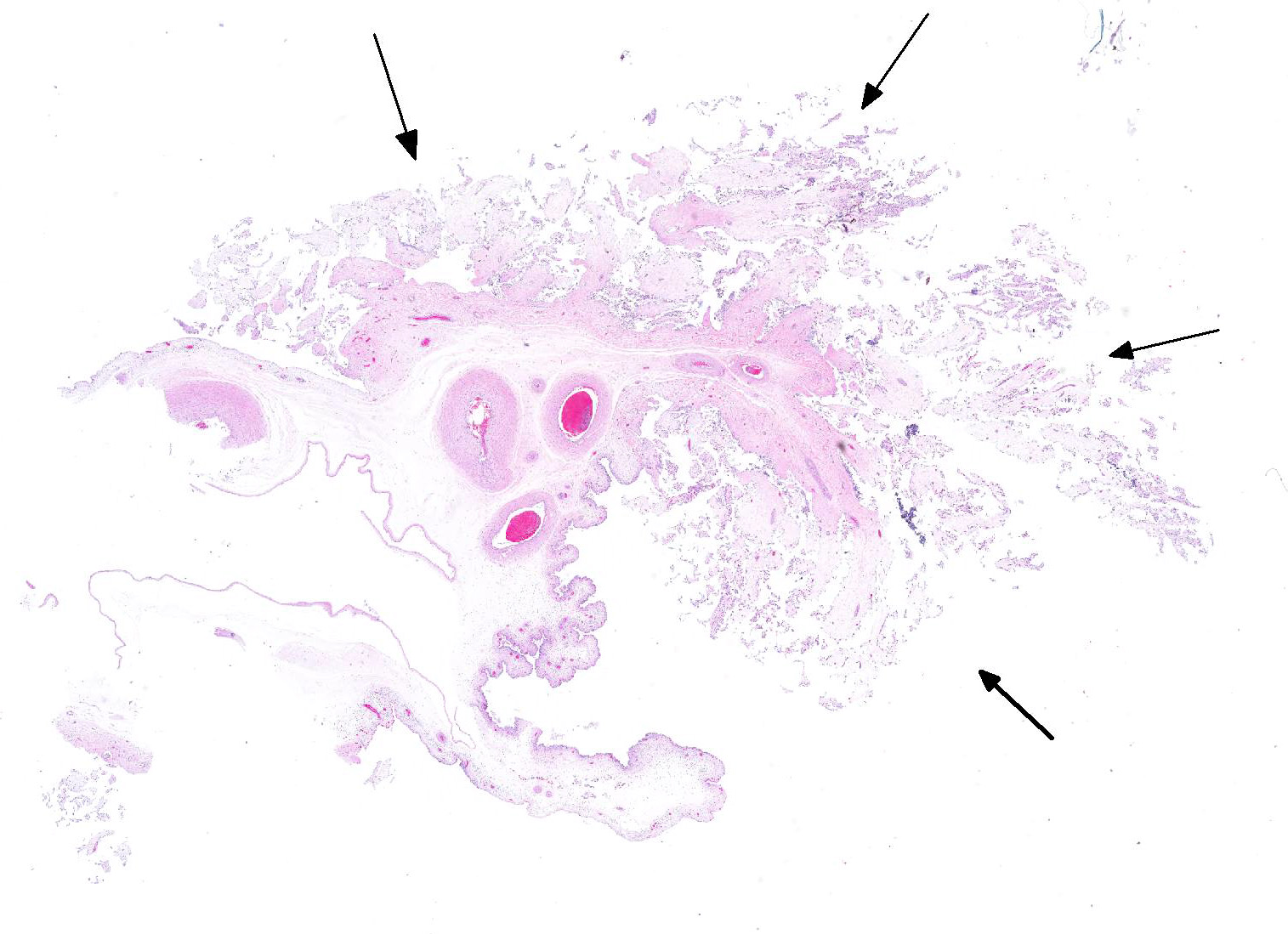

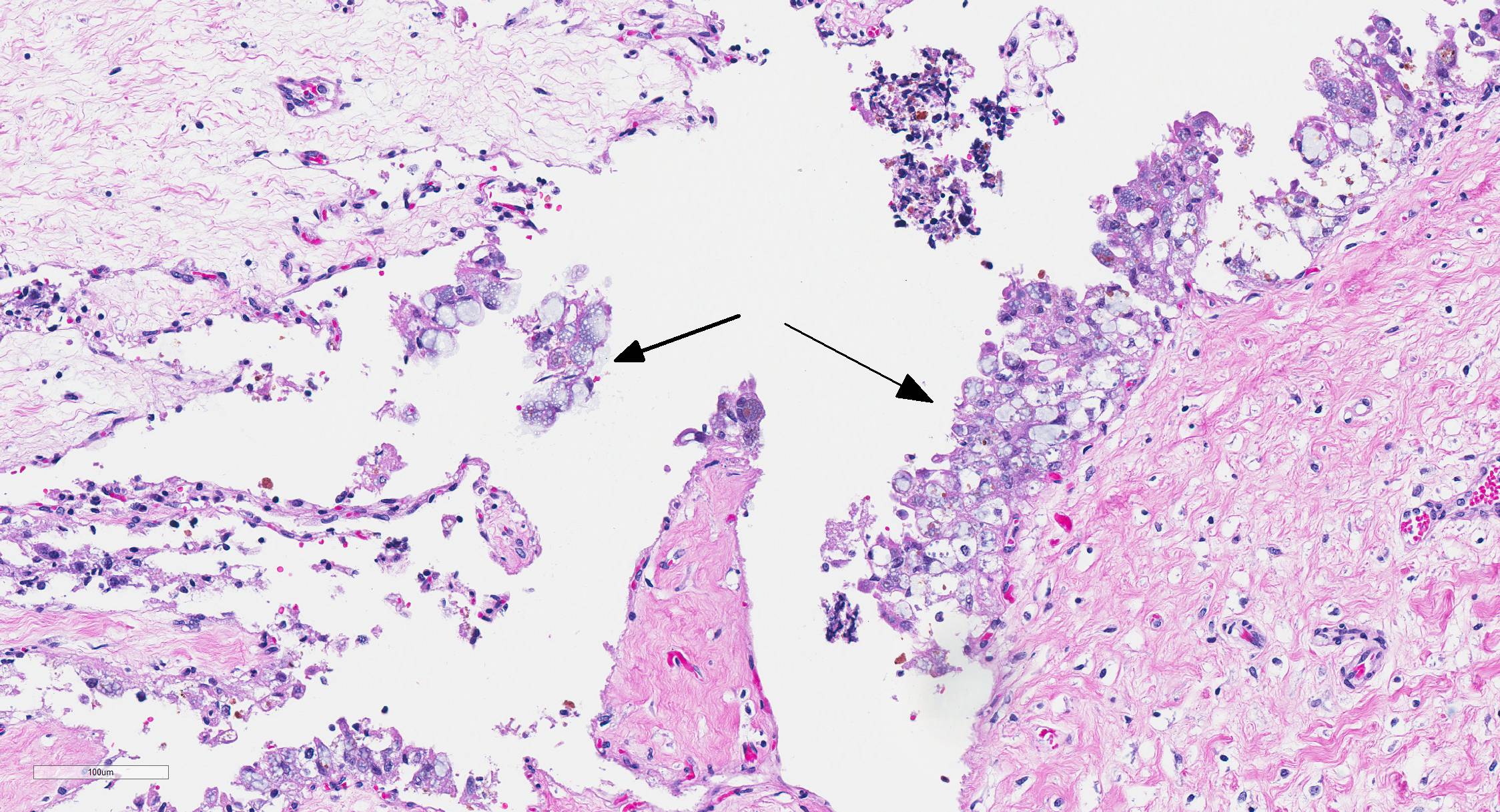

Microscopic Description:

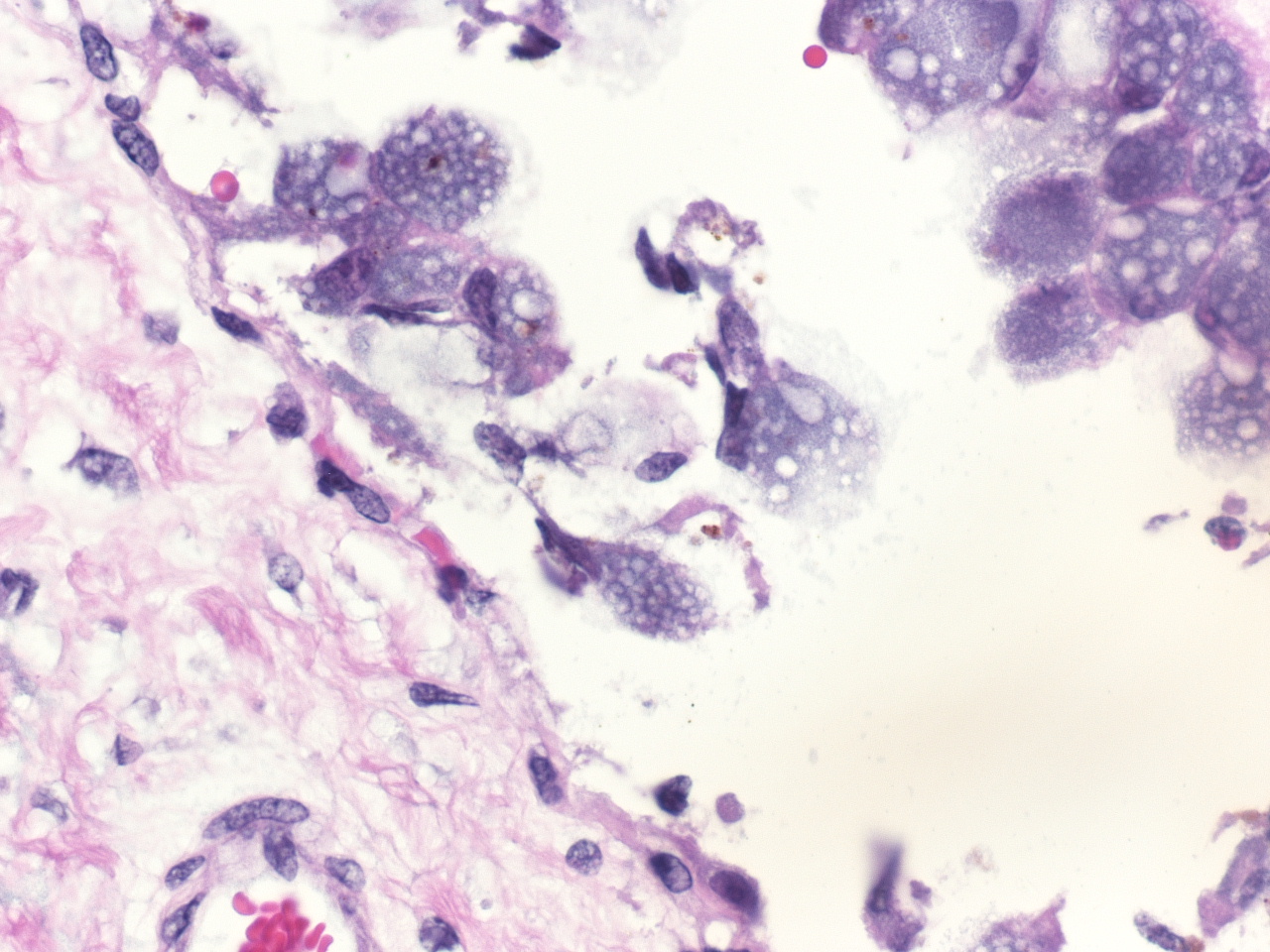

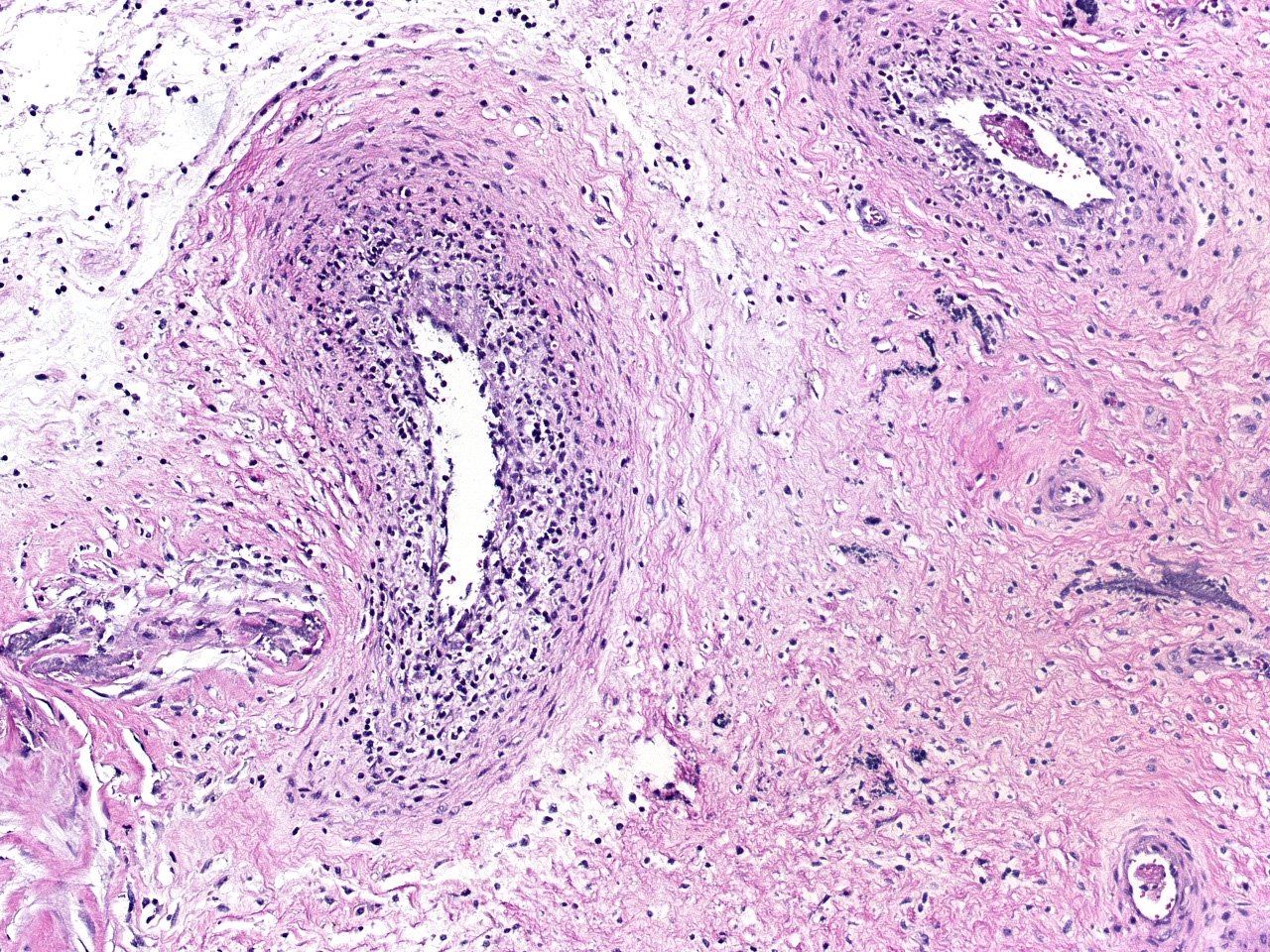

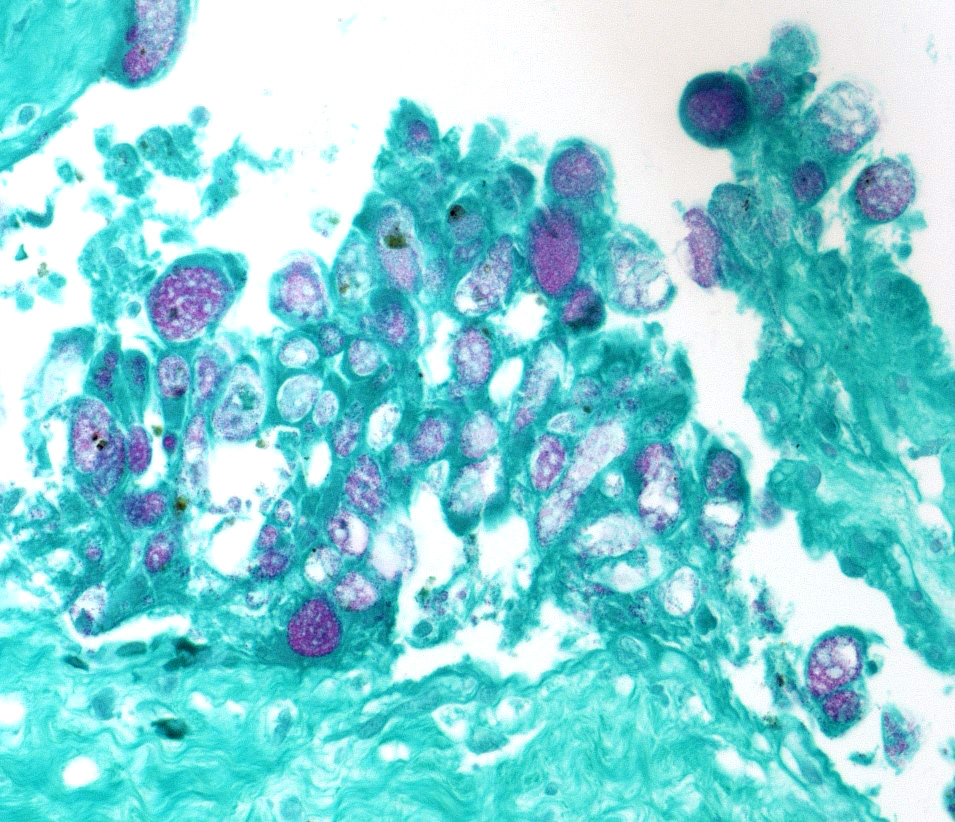

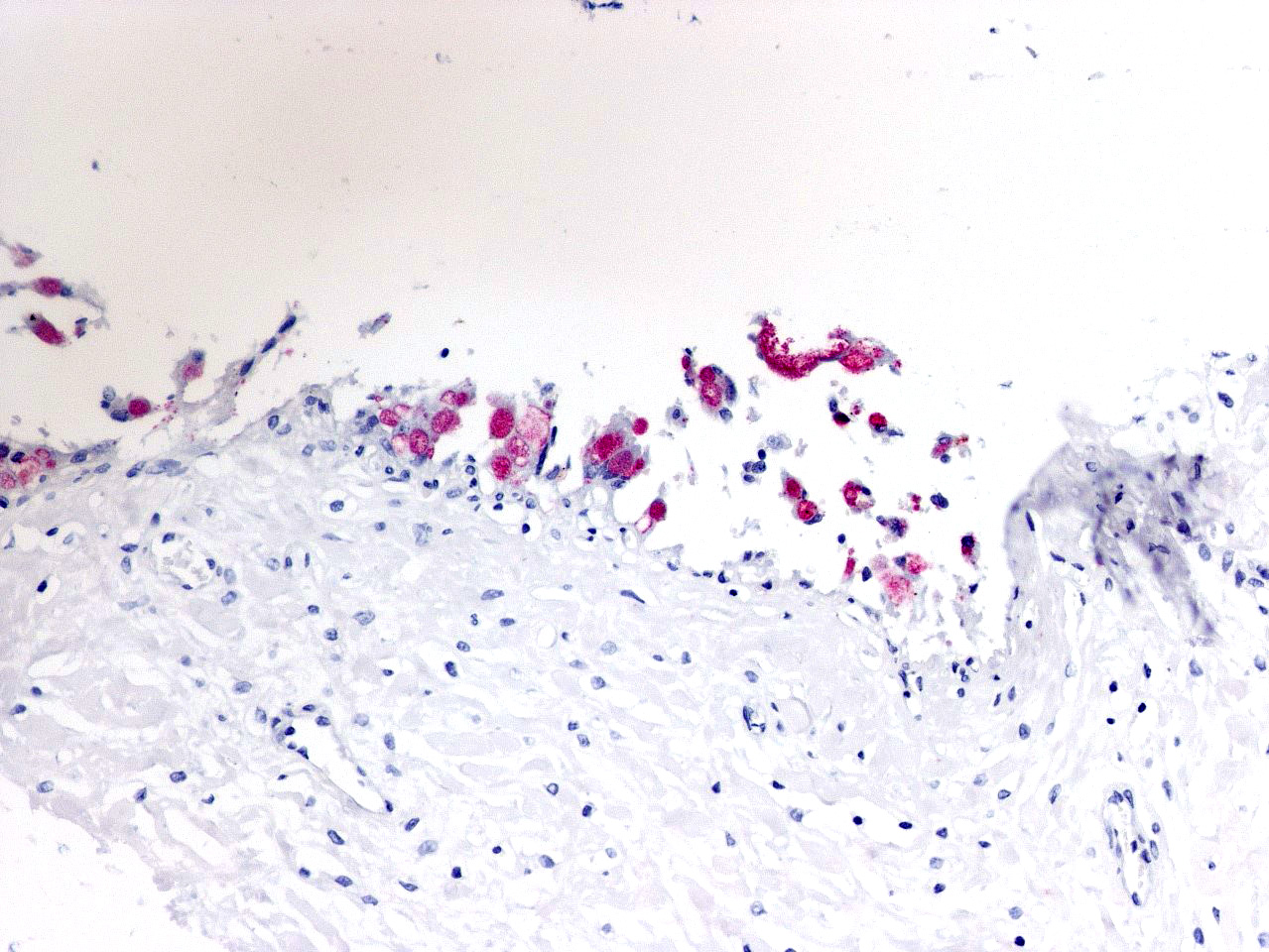

In sections of placenta from 2 fetuses, there were multifocal areas of necrosis and inflammation. Cotyledons and intercotyledonary placenta were infiltrated by neutrophils and macrophages. Fibrin admixed with degenerate inflammatory cells covered the cotyledonary surface. The intercotyledonary interstitium was infiltrated by inflammatory cells, and a few scattered blood vessels were necrotic and inflamed). Multiple chorionic epithelial cells were expanded by the presence of discreet vacuoles containing numerous bacterial organisms. Gimenez-tained sections highlighted the intracellular organisms. Gimenez-positive organisms were identified as Coxiella burnetii by immunohistochemistry.

Other lesions (not submitted) included multifocal gliosis within sections of cerebrum in two of the fetuses. No organisms were identified histologically. Sections of livers, lungs, spleens and kidneys had no histologic lesions.

Contributor´s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Multifocal necrotizing placentitis with vasculitis and intracellular bacterial organisms (Coxiella burnetii)

Contributor Comment: Coxiella burnetii is a well-recognized cause of abortion in sheep goats and, to a lesser extent, cattle.9 In one large study of goat abortions, C burnetii was second only to Chlamydia psittaci (Chlamydophila abortus) in numbers of cases of bacterial abortion in goats.6 Infected animals remain as a reservoir, shedding large numbers of organisms during subsequent abortions or at normal parturitions. Organisms are also shed in feces and milk,3 Ruminant reservoirs are the major source of infection in people, in whom the organism causes the zoonotic disease Q fever.1 Although cattle are major shedder of C burnetii, especially in milk6, the organism is not a major abortifacient in that species.5

Transmission is by inhalation or fecal-oral routes. Infected animals may abort in late gestation or give birth to weak kids. Fetal lesions are minimal but gross evidence of placentitis is present.9 Characteristic histologic lesions are necrotizing intercotyledonary placentitis with intracellular organisms; vascultitis is less prominent than in chlamydial placentitis. Both C burnetii and C abortus are Gimenez-positive. In this case, since antigen ELISA for Chlamydophila was positive, immunohistochemistry was needed to identify the organisms as C burnetii. C abortus should also cause multifocal necrosis in fetal liver and spleen, which was not seen in this case. This case was also interesting in that cerebral glial nodules suggested Toxoplasma infection, but PCR for T gondii on placenta and brain was negative.

The human disease Q fever, caused by infection with C burnetii, was first reported in Australia in 1935 but has a worldwide distribution.1. Only 40% of infected people show any clinical signs. The more common acute disease manifests as flu-like symptoms, pneumonia or hepatitis; chronic infections manifest primarily as endocarditis.2 Most reported cases are of the acute disease. Cases in the US are most often reported from western and plains states where ranching and rearing of cattle are common. Cases are most commonly reported in spring in summer, coinciding with birthing season for ruminants. Incidence of disease increases with age and persons with immune compromise, or those in contact with livestock are at higher risk.

C burnetii is an obligate intracellular organism in the order Rickettsiales. It infects monocytes and macrophages and survives within the acidic environment of the phagosome. Intracellular survival depends upon inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion. Control of the infection requires intact cell mediated immunity; lymphocytes of people with chronic infections fail to proliferate in response to C burnetii antigen, whereas lymphocytes of people with acute infections do respond.2

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology, and the Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-7034

JPC Diagnosis: Chorioallantois: Placentitis, necrotizing, diffuse,

severe, with multifocal moderate vasculitis, and numerous intratrophoblastic bacilli.

JPC Comment:

Coxiella burnetii, the causative agent of Q fever, is a bacterium whose wall is similar to that of a gram-negative bacillus; however, its wall does not stain with Gram stains, requiring a Gimenez stain to disclose its location.4 As an obligate intracellular parasite, it produces a reproductive vacuole that resembles a phagolysosome with an acidic pH, acid hydrolysates, and cationic peptides. To survive in this harsh environment, it has developed important buffering strategies, including the production of basic proteins, sodium-proton exchanges to combat oxidative stress ,and osmoprotectants to prevent osmotic damage.4 In vitro experiments have determined that there are actually two variants of the coccobacillus, a reproductively active "large-cell variant" which is the replicative form, and an environmentally stable small cell variant, which has numerous cross-links in its peptidoglycan wall to give it additional resistance to environmental stresses such as dessication, chemical, and heat stress.4

Q fever, short for query fever, was first identified

by Dr. John Derrick in meat-packing workers in Queensland Australia in 1935 who

developed an acute febrile illness but were negative on blood and serologic

tests for known pathogens at the time.7 Transmission to guinea pigs

and other laboratory animals ultimately resulted in the identification of

rickettsia within the spleen. The clinical signs of Q fever-high fever,

headaches and a slow pulse resembled other rickettsial diseases of the time

including typhus and psittacosis, but lacked the rash common to the other two

diseases. 7

In humans, Q fever has been seen in all countries except New Zealand. While

ruminants have been the traditional reservoirs, in recent years, a number of

additional species have been reported as shedding the bacillus, to include cats,

marine mammals, psittacines, reptiles, and ticks.4 In the absence

of a suitable host, C. burnetii also possesses the ability to utilize

free-living amebae as a reservoir for the small-cell, vegetative form.4

Q fever is most common seen in persons who come in contact with infected

animals, including farmers, abattoir works, lab workers, and veterinarians.7

Transmission has also been seen following ingestion of raw milk or fresh goat

cheese.7 Q fever has many various acute and chronic manifestations,

or may be asymptomatic. When it became a reportable disease in the US in 1999,

case numbers increased by 250% in the next 5 years.4 While it

most often presents as an influenza-like illness, more serious manifestations,

such as pneumonia, hepatitis, or endocarditis are seen. 10

Endocarditis is the most common chronic disease associated with C. burnetii

infection in humans and has been seen following valve transplants. 10

In cases of endocarditis, as vegetation may be absent of small, resulting in a

long latent period. 10

Between 2007 and 2010, a country-wide outbreak of Q fever occurred in the Netherlands with over 40,000 cases estimated, especially in the provinces of Noord-Brabant, Gelderland, and Limburg, centers of goat farming. The outbreak coincided with a marked increase in high-intensity dairy goat farming in proximity to urban areas. On some of these farms, abortion levels due to Coxiella exceeded 60%, leading to requirements for reporting of abortions and widespread immunization of goats. With cases still on the rise, in 2008, the Dutch government was forced to slaughter over 50,000 goats in order to minimize the public health risk.

The moderator discussed the presence of a brown granular pigment within the trophoblasts. While initially interpreted as hemosiderin by most participants, he offered the possibility of meconium and uptake by the trophoblasts. He noted the unusual lack of necrotic debris between the cotyledonary villi in this particular case. He also registered, during the description in this case, a personal enmity toward the words "admixed" and "coccobacilli".

References:

1. CDC Info, Q fever, Epidemiology and Statistics update June 2019. http://www.cdc.gov/qfever/stats/index.html

2. Angelakis E and Raoult D. Q fever. Vet Microbiol 2010; 140:297-309.

3. Berri M, Rousset E, Champion JL, et al. Goats may experience reproductive failures and shed Coxiella burnetti at two successive parturitions after a Q fever infection. Res in Vet Sci 2007; 83:47-52.

4. Eldin C, Melenotte C, Mediannikov O, Ghigo E, Millon M, Edouard S, Mege JL, Maurin M, Raoult D. From ! Fever to Coxella burnetii infection: a paradigm Change. Clin Micorbiol Rev 2017; 30(1) 115-190.

5. Garcia-Ispierto I, Tutusaus J, Lopez-Gatius F. Does Coxiella burnetii affect reproduction in cattle? A clinical update. Reprod Dom Anim 2014; 49:529-535.

6. Moeller RB. Cases of caprine abortion: diagnostic assessment of 211 cases (1991-1998). J Vet Diagn Invest 2001; 13:265-270.

7. Reimer LG. Q fever. Clin Micro Rev 1993; 6(3):193-198.

8. Rodolakis A, Berri M, Hechard C, et al. Comparison of Coxiella burnetii shedding in milk of dairy bovine, caprine and ovine herds. J Dairy Sci. 2007; 90:5352-5360.

9. Schlafer DM and Miller RB. Female genital system IN Jubb, Kennedy and Palmerâs Pathology of Domestic Animals, Vol. 1, 5th Edition, GM Maxie, ed. Elsevier Saunders, Edinburgh, 2007.

10. Weiner Well Y, Fink D, Schlesinger Y, Raveh D, Rudensky B, Yinnon AM. Q fever endocarditis; not always expected. Clin Micorbiol Infect 2010; 6:359-362.