Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 13

2 January, 2018

CASE III: 317048 (JPC 4033739).

Signalment: 15-year-old, Clydesdale-Cob cross, male castrated, horse (Equus caballus).

History: The animal presented to the Weipers Centre at the University of Glasgow for re-evaluation of episodes of syncope that had been noted sporadically over the preceding two years. The horse had been investigated for syncope associated with polycythaemia and elevation of cardiac troponin (CTnI). Cardiac dysrhythmias had resolved over time, with correction of red cell count and CTnI levels. Since then, the horse had returned to ridden exercise with no observed collapses until one week before presentation when it went down into lateral recumbency, paddled with his front legs and chomped his lips, appearing to have lost consciousness, the eyes appeared vacant and the horse remained down for two to three minutes after which he recovered and appeared normal. On presentation the horse was bright and alert and in good body condition (613kg). The syncopal episodes had implications for horse welfare and human safety, therefore the owner elected euthanasia.

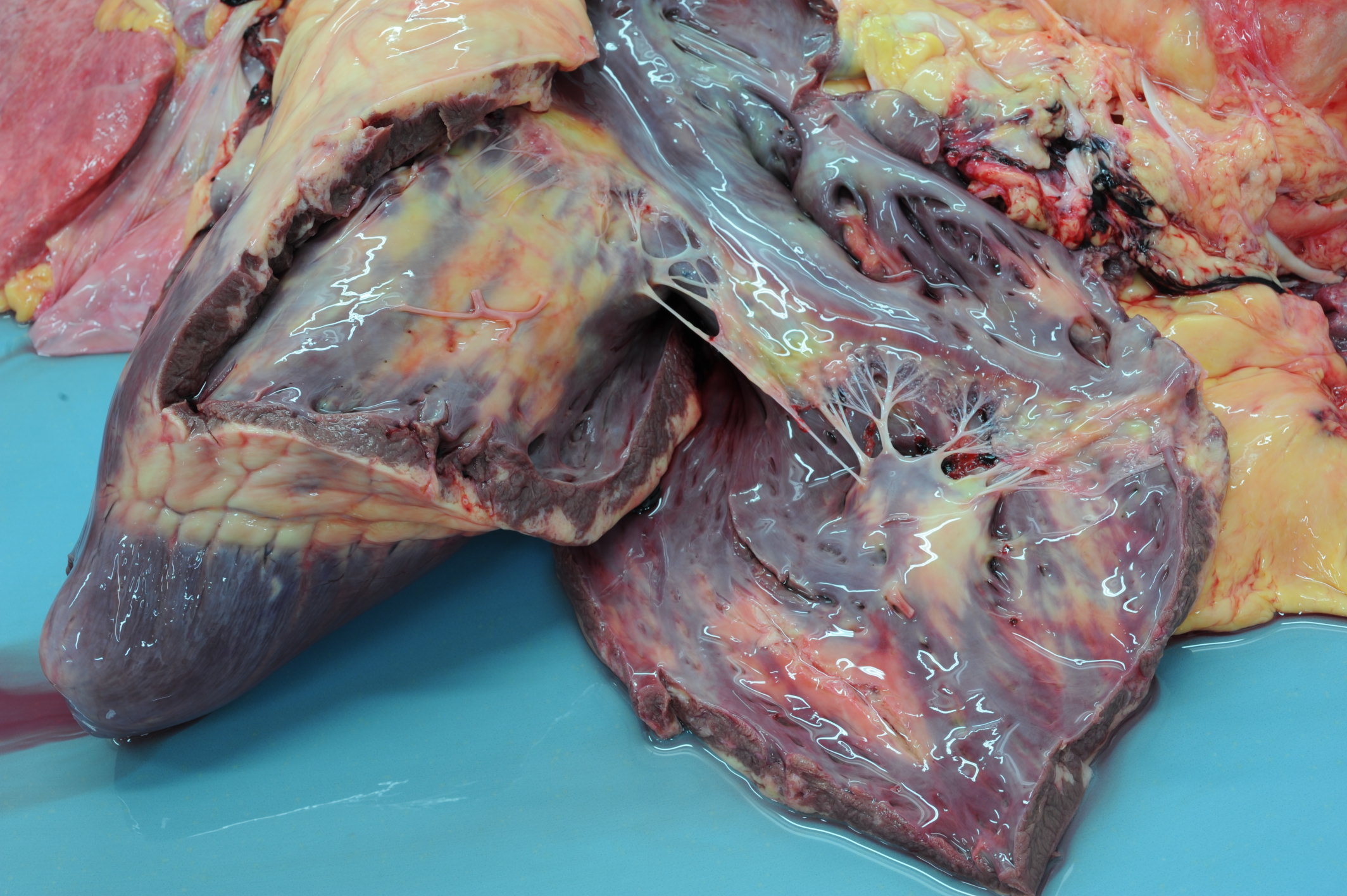

Gross Pathology: On macroscopic examination, the epicardium of the right ventricular free wall was replaced by a yellowish soft material that expanded extensively from the coronary arteries towards the center of the ventricle and was also multifocally distributed in small foci within the remaining myocardial fibers, which accounted for less than 40% of the total right ventricle. Upon opening the right ventricle, the endocardium was similarly replaced by this abnormal tissue extending multifocally up to 1cm deep into the myocardium from both the epicardium and endocardium. The left ventricle was similarly affected, with approximately 20% of the myocardial tissue being replaced by yellowish soft tissue. Small foci of this yellowish tissue were also multifocally observed in both the left and right atria. No other significant gross pathologic findings were observed in other organ systems.

Laboratory results: Haematology and biochemistry profiles were unremarkable. Serum amyloid A and fibrinogen were within normal limits. CTnI was within reference range. On ECG examination there were multiple short periods of sinus tachycardia with no apparent external stimuli and also one episode of profound tachycardia, four ventricular premature complexes were also present. Echocardiography and neurological evaluation were unremarkable.

Microscopic Description:

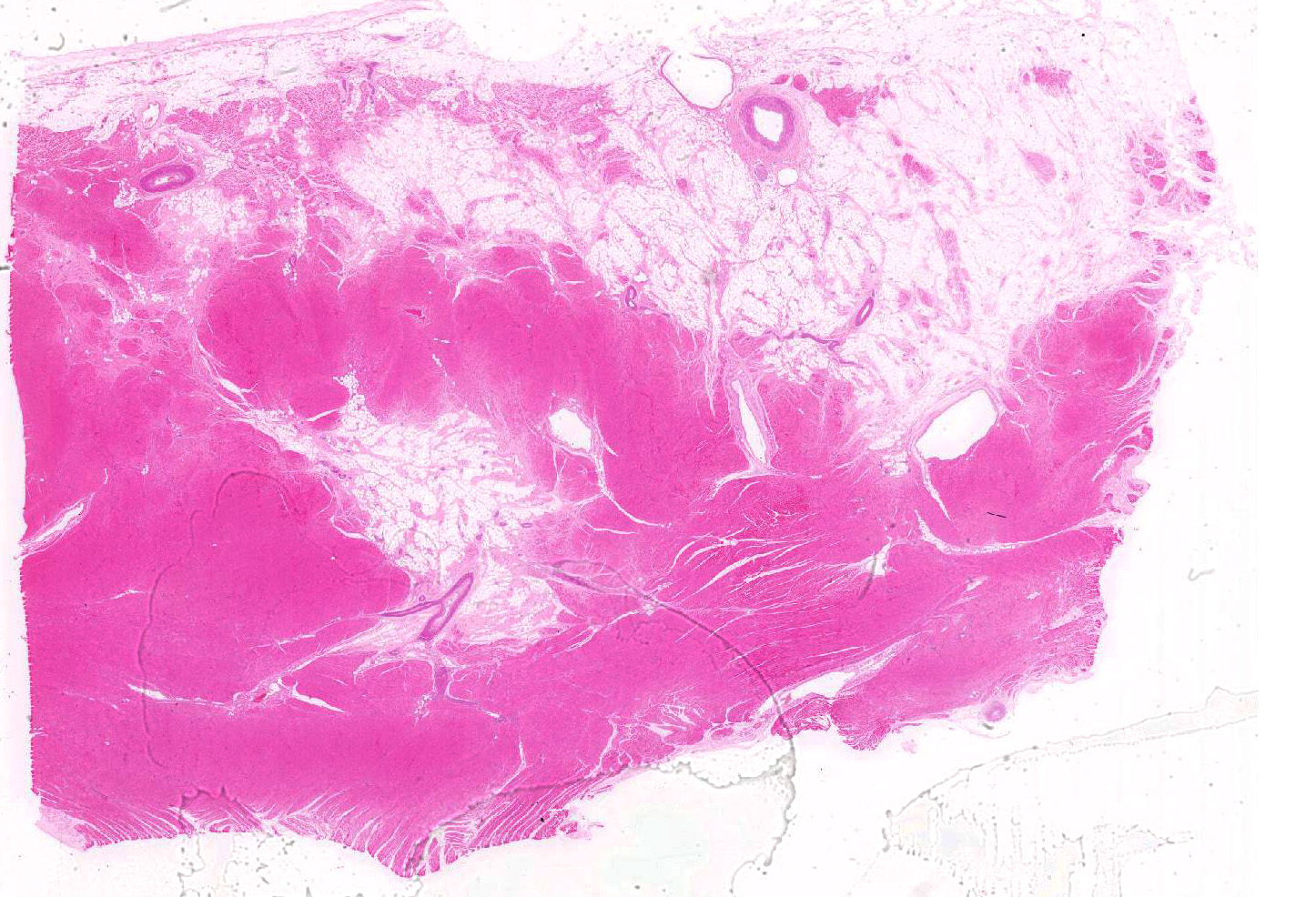

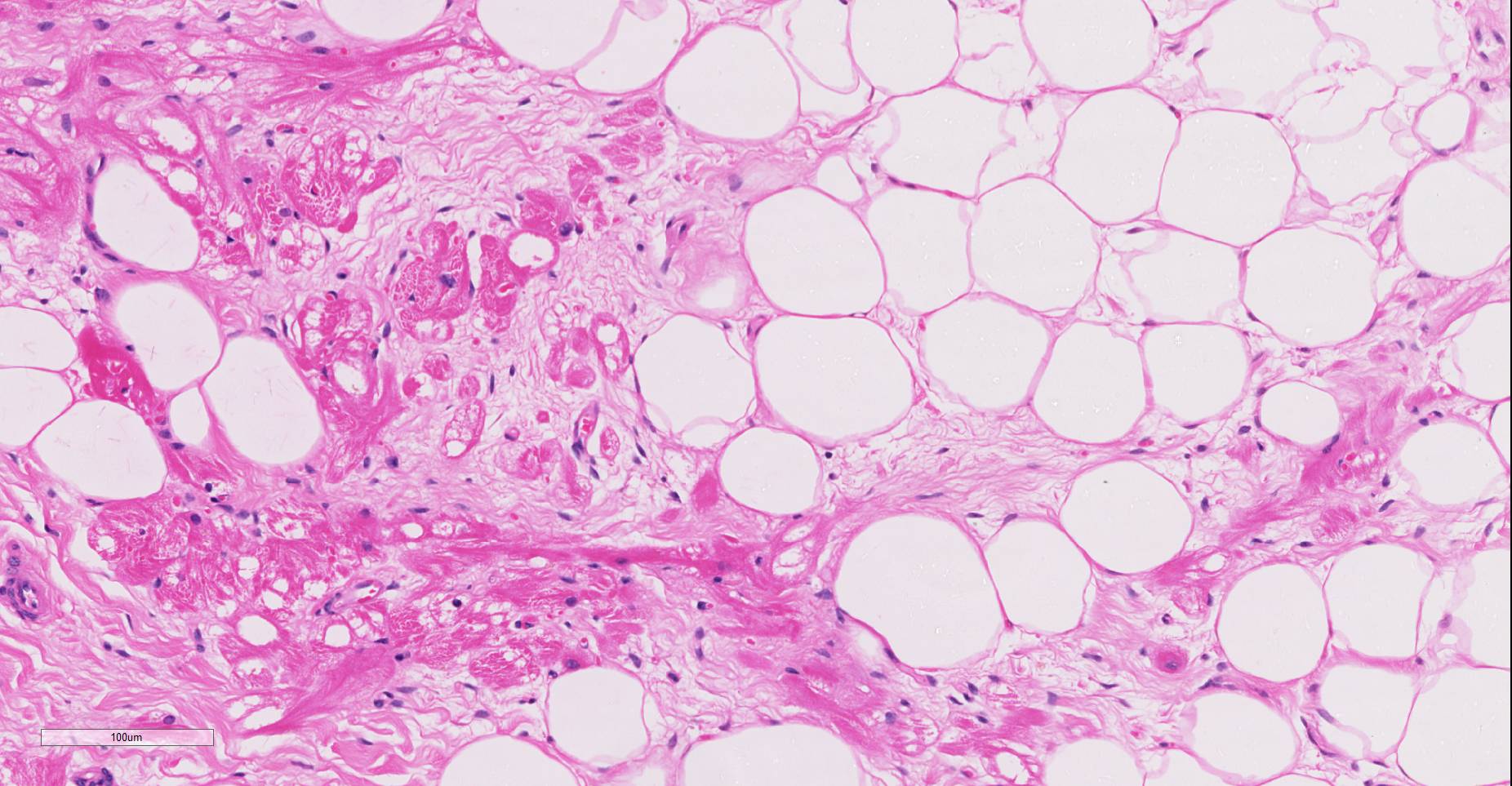

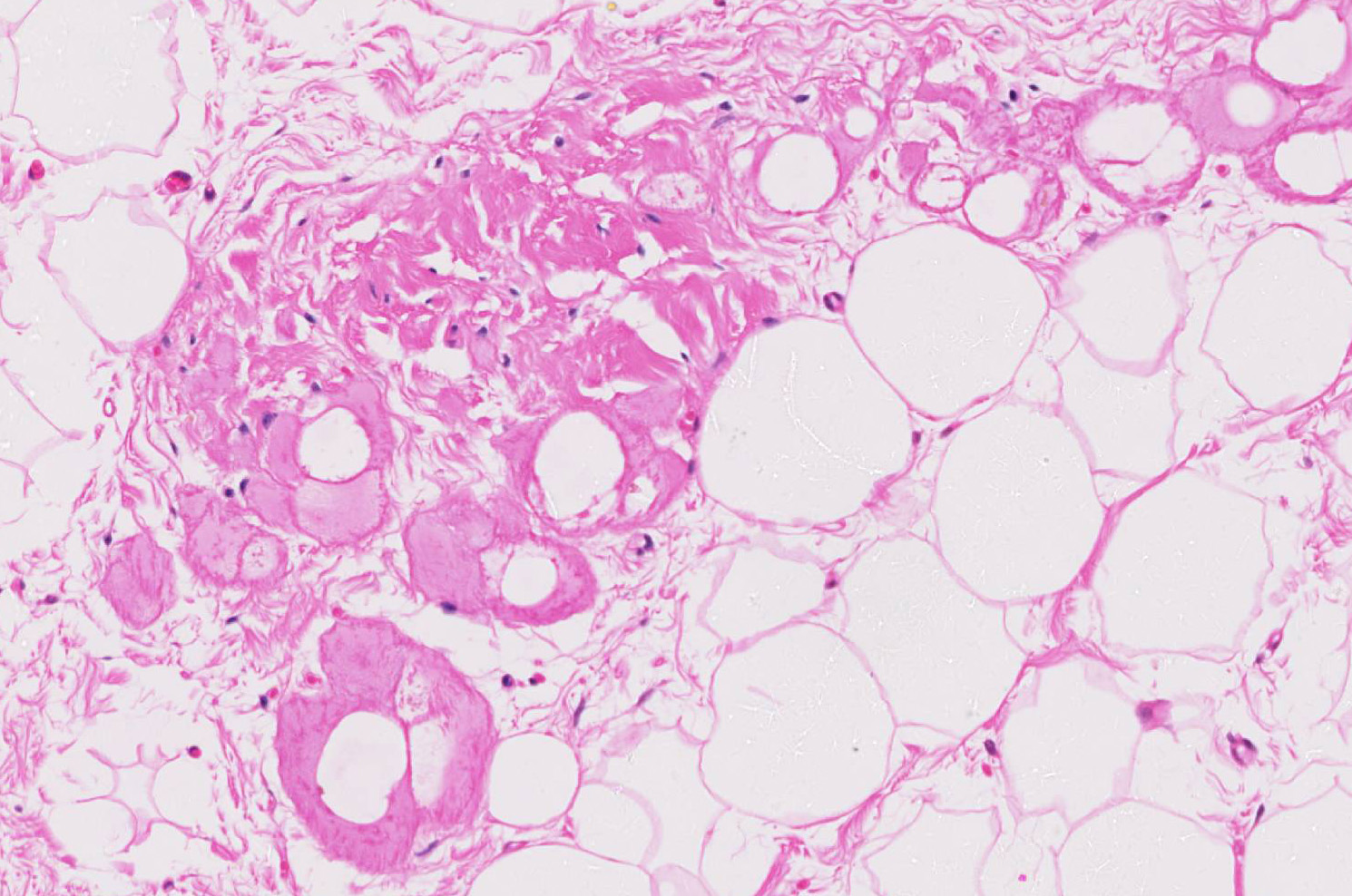

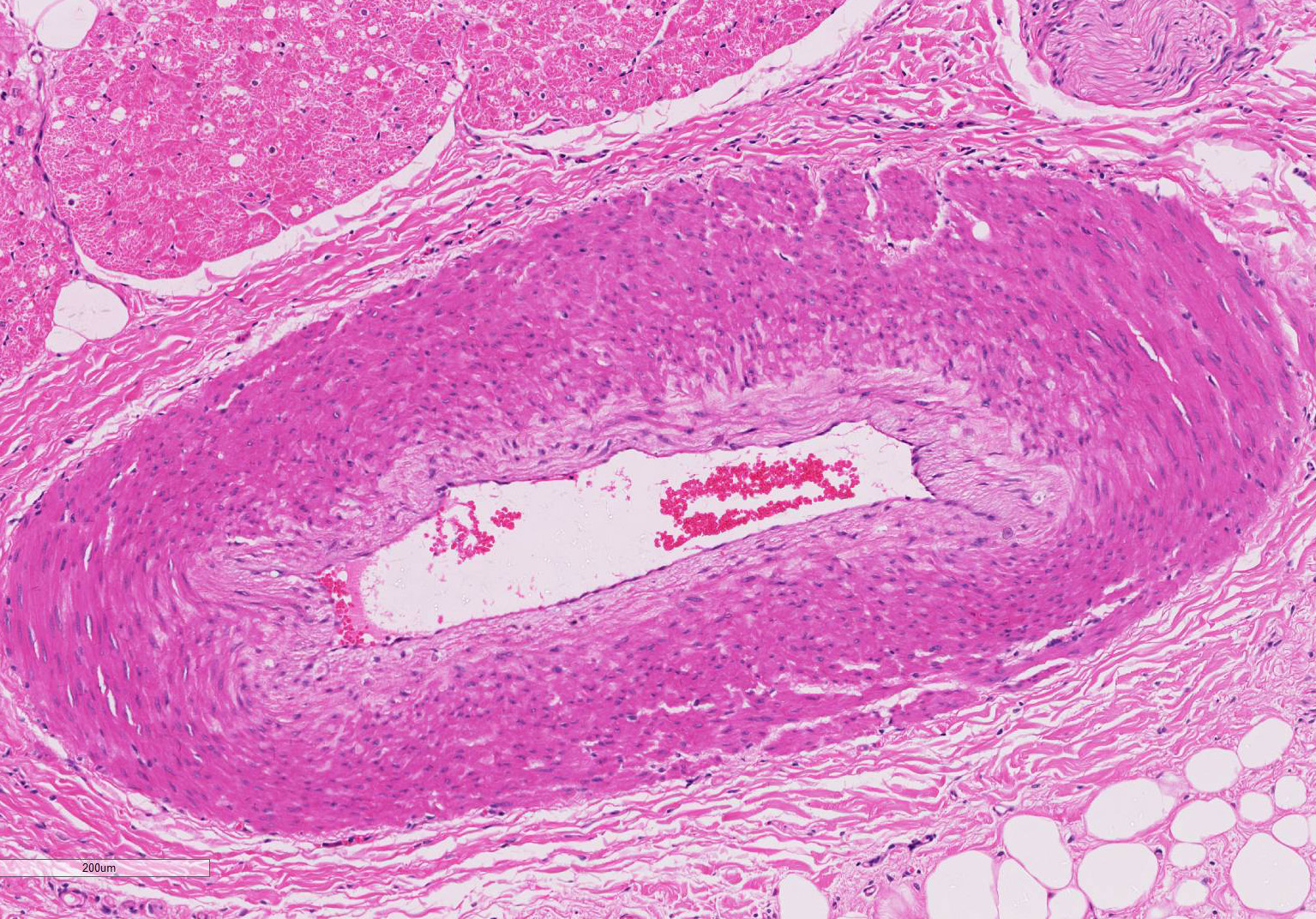

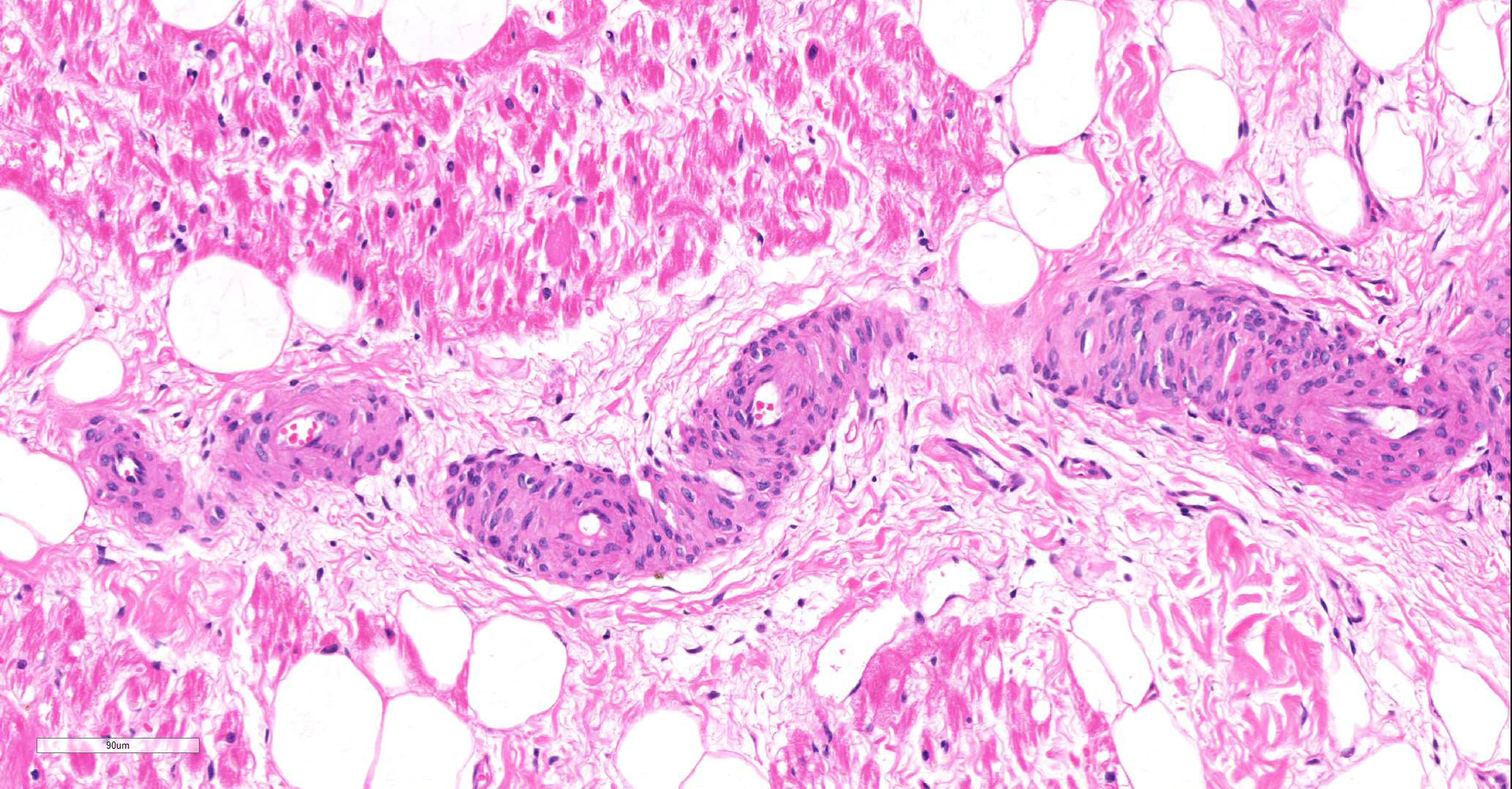

Microscopic findings were similar in both ventricles, being more extensive in the right ventricular free wall; and similar to those previously described in horses. Cardiomyocytes extensively within subepicardial zone and multifocally within the myocardial and subendocardial areas are markedly reduced in number and replaced by abundant adipose tissue intermixed with variably thickened bundles of fibrous connective tissue. Residual cardiomyocytes within the adipose tissue or surrounding it are highly vacuolated, and often with loss of myofibrils and nuclear detail (degeneration). Interspersed within the fibrous and adipose tissue infiltrate are low numbers of mononuclear inflammatory cells, mainly lymphocytes and macrophages. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain highlighted the disruption of Purkinje fibres by adipose tissue. Masson’s trichrome stain highlighted the variably thickened bundles of fibrous connective tissue dissecting the myofibers.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Myocardial degeneration, focally extensive, severe, chronic; with marked adipose tissue replacement with fibrosis, myocardium, Clydesdale-Cob cross, male castrated, horse (Equus caballus).

Contributor’s Comment: Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy is a well-recognized entity in human beings from which clinicopathological features were described in 1982.5,15 The condition has also been described in Boxer dogs1,6 and cats2 with similar gross and histological appearances; reports of this similar condition in breeds of dogs other than Boxer has also been described.9 Recently, a similar condition was diagnosed in two horses3 that died with no previous signs and in which both hearts were bearing fibro-fatty replacement similar to the case we present here.

While the two previous equine cases died without showing clinical signs, in this case there is a prolonged history of collapse and cardiac dysrhythmias. Young human cases are presented most commonly with cardiomegaly, congestive heart failure or sudden death5,14 while adult patients usually have a more extensive history of recurrent ventricular arrhythmias and ventricular tachycardia.5 Clinical signs in Boxer dogs vary widely from sudden death to congestive heart failure with or without arrhythmias6 while cats usually do not present any signs of arrhythmia and die due to congestive heart failure.2

This cardiomyopathy is a human familial condition of autosomal dominant inheritance with various degrees of penetrance.4 Mutations in genes involved in cell adhesion complexes such as desmoglein-2 (GSG2) or plakophilin-2 (PKP2) have been found to be associated with ARVC in humans1, which supports the hypothesis that this condition is caused by inadequate cell-to-cell adhesion between cardiac myofibers leading to detachment of cardiomyocytes, cell death and replacement by adipose tissue with fibrosis.4 Several desmosomal genes and the cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2) gene (involved in excitation–contraction coupling across the ventricles and mutated in some unique forms of human ARVC) have been investigated in boxer dogs with no positive relationship established.7,8,16 This could be, however, due to the substantial genetic heterogeneity of the disease.

With only three cases reported in horses, it is difficult to determine correlation between sex, age or exercise. However, the three cases were all male horses of heavy breeds (Clydesdale and Cob) in the same geographic region, which could possibly indicate a genetic relationship as is observed in many human cases.14

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Diagnostic Services, School of Veterinary Medicine

College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow

Bearsden Road

G61 1QH

Glasgow, United Kingdom

JPC Diagnosis:

Heart, ventricle: Fibrofatty infiltration, subepicardial and myocardial, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with cardiomyocyte, atrophy, and loss.

JPC Comment:

The uncommon syndrome of humans and Boxer dogs (often referred to as “Boxer cardiomyopathy”) of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy is poorly named, as the evolving literature has identified cases in which degenerative lesions (and subsequent generation of arrhythmias) may arise in the atria and frequently, the left ventricle.

While mutations in several desmosomal genes have been identified as causative in the human condition, and a loss of desmosomal integrity has been identified in affected Boxers, mutations of desmosomal genes have not yet been identified in the Boxer model.10 Striatin, a scaffolding protein localized to intermediate filaments and the intercalated disk has been proposed as a potential cause in the Boxer. Decreased Wnt signaling in the myocardium of genetically engineered mouse models of ARVC appears to be responsible for increased myocardial adipo- and fibrogenesis, stimulating abnormal cell proliferation and differentiation as a result of beta-catenin accumulation in the cytoplasm of cardiac progenitor cells. Abnormal levels of beta catenin and mislocalization of this protein as well as striatin have been identified in affected Boxers.10

The veterinary literature is sparse with regard to this entity in the horse. This particular case was reported in the literature in 201512, bringing the total number of reported equine cases to three. In previous studies of cardiac muscle in several equine populations, including racing, working, and a general population, fibrofatty infiltration has not been identified as a post-mortem finding. Similar changes were noted within the right ventricle of the two other reported equine cases.12 The microscopic changes noted in this entrapped myofibers are also commonly seen in the human cases, to include cytoplasmic vacuolation and nuclear dysmorphism.11

ARVC has also been reported in two related chimps in a zoo collection (14 and 16 years of age) with no premonitory signs. A predominance of fibrofatty infiltration over the traditional interstitial fibrosis of the so-called “fibrosing cardiomyopathy”, considered the predominant form of heart disease in this species.17

A number of questions remain about the pathophysiology of this fascinating disease. Why are changes most prominent in the right ventricle? Current theory points to the thin wall and increased distensibility of the right ventricle which predisposes it to desmosomal failure;13 the identified cases of ARVC involving the atria as well as left ventricle does not put this pathogenesis into dispute. There is dispute within the literature as to whether the lesion is the result of abnormal proliferation or an aberrative repair response – earlier studies such as the one in the feline model of ARVC identified a much higher number of cases with myocardial inflammation to a level not identified in other models2; their association of inflammation and fibrofatty repair was made prior to identification of causative genes in human cases and generation of genetically engineered mouse models.

References:

- Basso C, Fox PR, Meurs KR. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy causing sudden cardiac death in Boxer dogs: a new animal model of human disease. Circulation 2004; 109:1180-1185.

- Fox PR, Maron BJ, Basso C.. Spontaneously occurring arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in the domestic cat: A new animal model similar to the human disease. Circulation 2000; 102:1863-1870.

- Freel KM, Morrison LR, Thompson H, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy as a cause of unexpected cardiac death in two horses. Veterinary Record. 2010; 166:718-722.

- Kies P, Bootsma M, Bax J, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: Screening, diagnosis and treatment. Heart Rhythm. 2006; 3(2):225-234.

- Marcus FI, Fontain GH, Guiraudon G. . Right ventricular dysplasia: a report of 24 adult cases. Circulation. 1982; 65: 384-398.

- Meurs KM, Spier AW, Miller MW. Familial ventricular arrhythmias in boxers. J Vet Intern Med. 1999; 13:437-439.

- Meurs KM, Lacombe VA, Dryburgh K, et al. Differential expression of the cardiac ryanodine receptor in normal and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy canine hearts. Hum Genet 2006; 120:111–118.

- Meurs KM, Erderer MM, Stern JA, et al. Desmosomal gene evaluation in Boxers with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Vet Res.2007; 68(12):1338-1341.

- Nakao S, Hirakawa A, Yamamoto S, et al. Pathologic features of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in middle-aged dogs. J Vet Med Sci 2011; 73(8):1031-6.

- Oxford EM, Danko CG, Fox PR, Kornrich BG, Moise NS. Change in beta catenin localization suggests involvement of the canonical Wnt pathway in Boxer dogs with arrhymogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Vet Intern Med 2014; 28:92-101.

- Pilichou K, Nava A, Basso C, et al. Mutations in Desmoglein-2 Gene Are Associated With Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006; 113:1171-1179.

- Raftery AG, Garcin NC, Thompson HT, Sutton DGM. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy secondary to adipose infiltration as a cause of episodic collapse in a horse. Irish Vet J 2015;68:24. Doi 10.1186/s13620-015-0052-3.

- Sen-Chowdry S, Morgan RD,Chaamber JC. Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: etiology diagnosis, and treatment. Ann Rev Med 2010; 61:233-253.

- Thiene G, Nava A, Corrado D, et al. Right ventricular cardiomyopathy and sudden death in young people. N Engl J Med. 1988; 318(3):129-133.

- Thiene G, Basso C. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: An update. Cardiovascular pathology. 2001; 10:109-117.

- Tiso N, Stephan DA, Nava A, et al. Identification of mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene in families affected with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 2 (ARVC2). Human molecular genetics. 2001; 10(3):189-194.

- Tong LJ, Flach EJ Sheppard MN, Pocknell A, aenerjee AA, Boswood A, Bouts T, Routh A, Feltrer. Fatal Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in two related subadult chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Vet Pathol 2014; 51(4): 858-887.