Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 7

October 17, 2018

CASE III: 15/444 (JPC 4068158-00).

Signalment: 20-year-old horse, Appaloosa, unknown sex (Equus caballus)

History: The horse was blind on the left eye, and had glaucoma that was suspected to be secondary to chronic (possibly recurrent) uveitis and posterior lens luxation. The eye was enucleated due to increased ocular pressure that could not be medically controlled, and submitted for histopathological examination.

Gross Pathology: The lens of the eye was posteriorly luxated and attached in only a few lens fibers. Other gross changes were not detected.

Laboratory results: N/A.

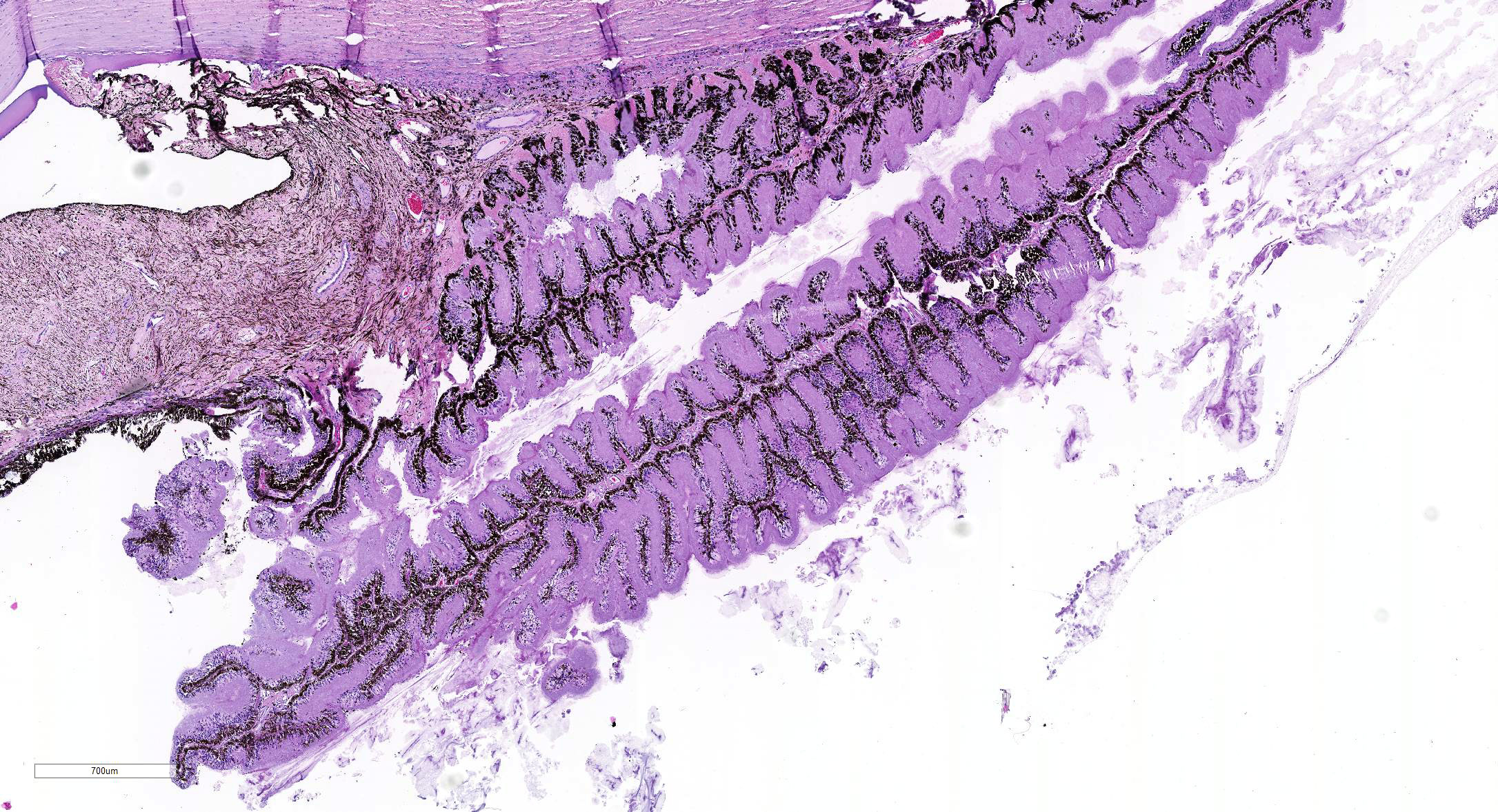

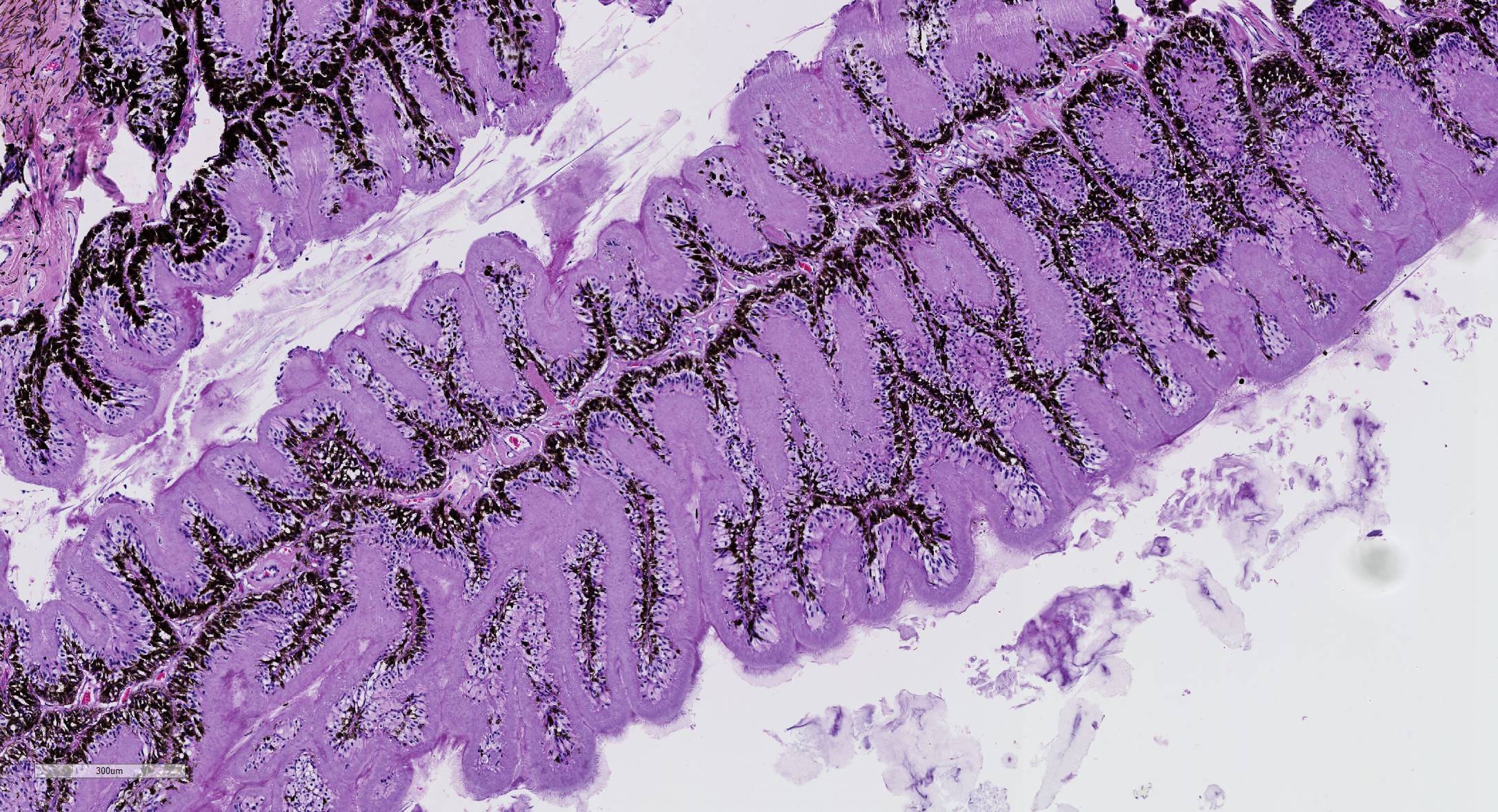

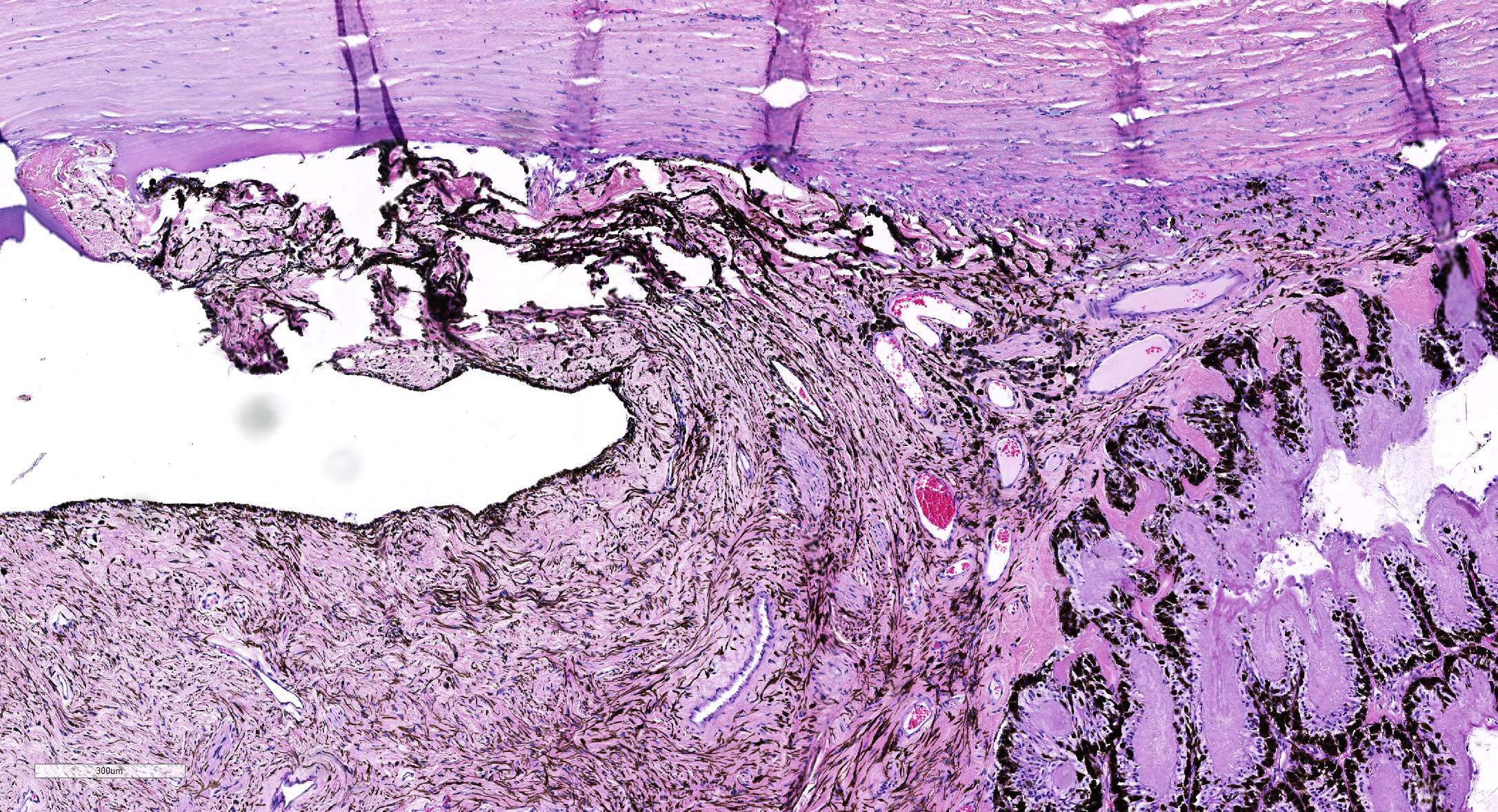

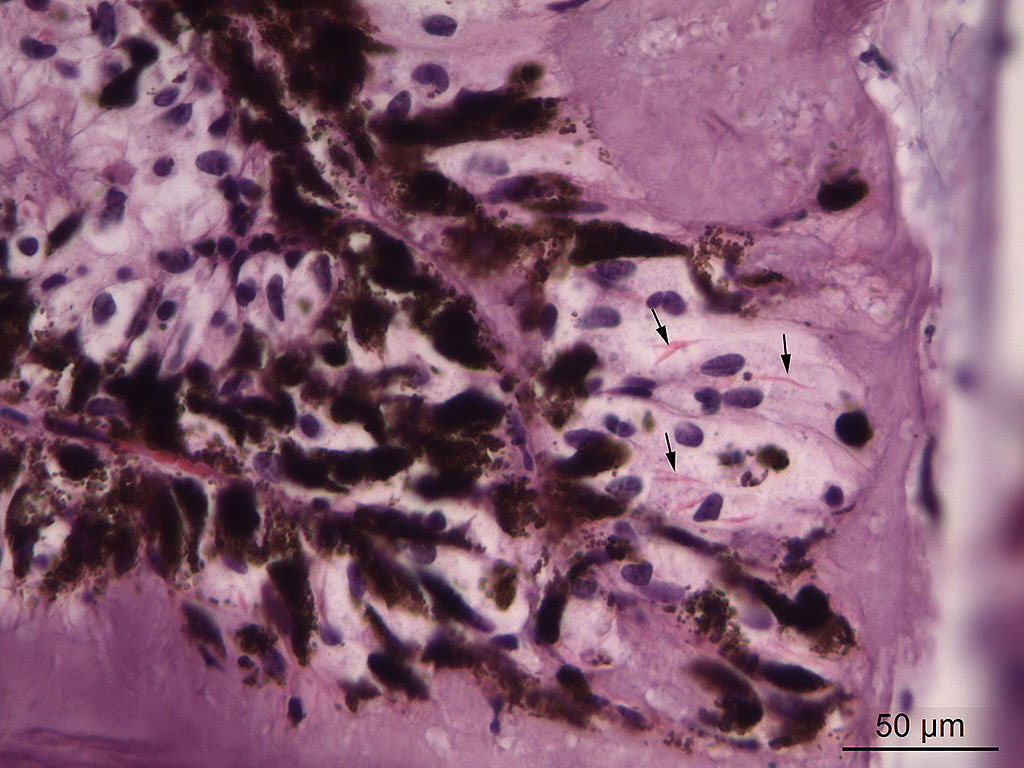

Microscopic Description: Eye, horse: In the conjunctiva, there was a mild lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. Multiple ruptures was observed in the Descemet’s membrane in conjunctiva. The filtration angle appeared to be pressed posteriorly, and consisted of compact tissue without obvious trabecular tissue. The iris appeared normal. Along the non-pigmented epithelium of the ciliary body, there was a diffuse thick membrane consisting of eosinophilic homogeneous to slightly fibrillar material. Intensely eosinophilic rod-shaped inclusions were found in some of the non-pigmented epithelial cells. There was a very mild multifocal infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the ciliary body. The retina was atrophic, with few ganglion cells, a thin inner nuclear layer that multifocally merged with the outer nuclear layer. In the lens, there was mild multifocal degenerative changes.

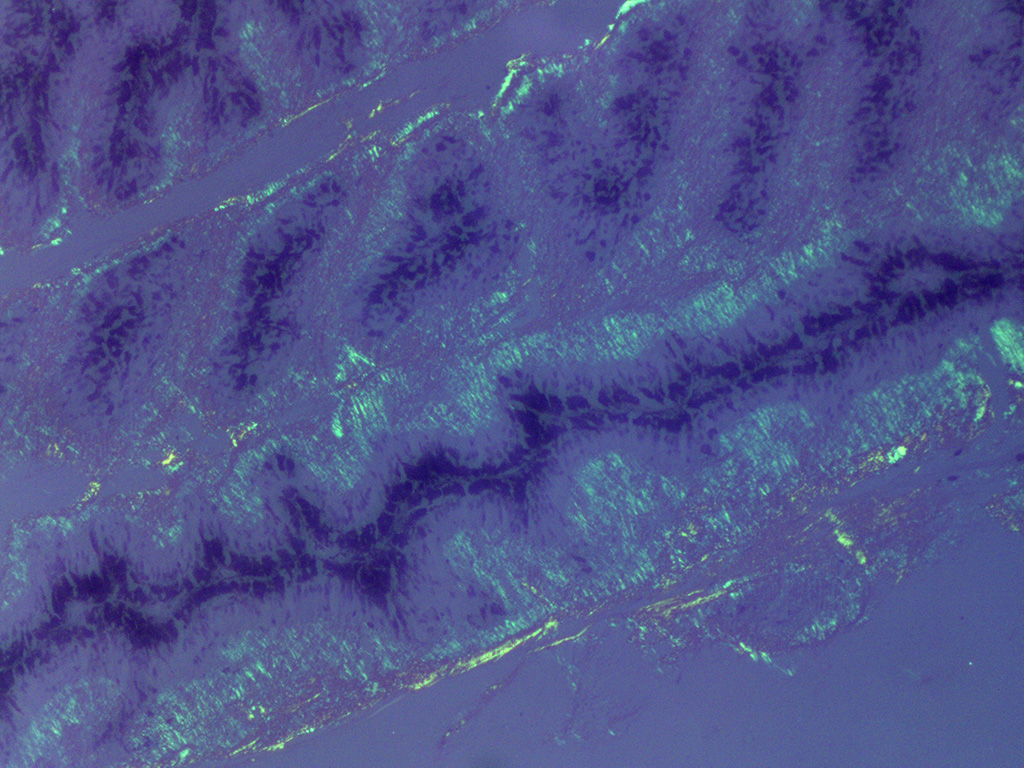

In Congo-red stained sections, there was intense positive apple green birefringence under polarized light (amyloid) in the eosinophilic membrane associated with the non-pigmented epithelium. Small amounts of positive material was also detected in the filtration angle and the iris. In some sections, there are vascular invasion in the cornea and corneal edema.

Due to the large size of the eye, pieces containing limbal cornea, iris, ciliary body and anterior sclera, choroid and retina was excised for submission for Wednesday Slide Conference. In a few sections the tip of the iris is missing in the slide, however as described above this area of the ocular tissue was without morphological lesions. The number of intracytoplasmic inclusion and inflammatory infiltrates were few, and thus not present in every slide. The main lesion, the amyloid, was extensive and is present in every slide.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Eye, ciliary body: amyloidosis, severe, diffuse with mild multifocal lymphoplasmacytic uveitis and ciliary non-pigmented epithelial intracytoplasmic inclusions

Eye: secondary glaucoma and posterior lens luxation

Contributor’s Comment: Equine recurrent uveitis is a leading cause of blindness in horses. The cause is unknown, and autoimmune disease, infection with leptospires or a stereotypic response to chronic intraocular inflammation following a variety of insults have been proposed to cause the disease.2,5,6,11,12 Inflammation in the ciliary body of this horse was very mild and consisted of multifocal infiltration of few lymphocytes and plasma cells. Another histopathologic feature of equine recurrent uveitis in the horse is rod-shaped intracytoplasmic inclusions in the non-pigmented ciliary epithelium,1,4 and although sparse, such inclusions were present in this case.

The most striking lesion was the thick eosinophilic membrane associated with the non-pigmented ciliary epithelium that was confirmed to be amyloid in Congo red stained slides viewed under polarized light. This finding is by some authors considered to be specific for equine recurrent uveitis and diagnostic for the condition.4,13 The ocular amyloid in two horses suffering from equine recurrent uveitis was characterized immunohistochemically and by mass spectrometry to be localized ocular AA amyloid.9 Several morphologic features in the ciliary body in the eye from this horse was consistent with equine recurrent uveitis: amyloid deposition - lymphoplasmacytic uveitis and intraepithelial eosinophilic rod shaped inclusions - although the two latter were very mild.

Contributing Institution:

Institute of Basic Sciences and Aquatic Medicine,

Norwegian University of Life Science, School of Veterinary Medicine www.nmbu.no

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Eye, surface of ciliary body: Amyloidosis, diffuse, severe.

- Eye, iris: Anterior synechiae with occlusion of the iridocorneal angle.

JPC Comment: Ocular amyloidosis is an uncommon finding in the horse; to date, all reported cases of intraocular amyloid have been associated with equine recurrent uveitis. Conjunctival amyloid has also been identified in the horse eye, most often in conjunction with nasal amyloidosis.10

Several syndromes have been identified with amyloidosis in the horse. Systemic amyloidosis occur secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions, horses used for the production of immunoglobulins, and neoplasia. Reactive systemic amyloidosis (seen in chronic inflammatory conditions and immunoglobulin-producing horses) results from the production of excessive serum amyloid A (SAA), and deposition of the non-degradable protein within tissues. SAA is preferentially deposited in the liver but may also be seen in the spleen, kidneys, GI tract, adrenal glands, and lymph nodes. Systemic amyloidosis resulting from the deposition of amyloid light chains (AL) is rare in the horse and has been seen in association with multiple myeloma.6

There are several forms of localized amyloidosis in the horse as well. Nasal amyloidosis results from the nodular deposition of AL amyloid within the nasal cavity and elsewhere in the respiratory system. These deposits may result in epistaxis, stertor, exercise intolerance, and nasal obstruction. Conjunctival amyloid deposits have been seen in two cases. Progression to systemic AL amyloidosis has not been reported in the horse.10

A final type of localized AL-amyloidosis seen in the horse is cutaneous amyloidosis (and has also been documented in man, dogs, and cats. In the horse, these nodules are most often seen within the panniculus of the head, neck, shoulders and chest, and may be associated with granulomatous dermatitis and panniculitis.8 They may wax and wane, and of the cases that have been associated with extraskeletal plasmacytoma and lymphoma, a pathogenesis for most cases has not yet been identified. They are occasionally seen with other forms of localized amyloid, but not with systemic forms of amyloid in the horse.8

According to the pathologists of the Comparative Ocular Pathology Laboratory of Wisconsin (COPLOW), equine recurrent uveitis (ERU) is the most common cause of cataract, glaucoma, phthisis bulbi, and blindness in the horse. It is characterized by recurrent bouts of inflammatory disease resulting in progressive ocular degeneration. Its pathogenesis has not been definitively established, although previous infection with various Leptospira serovars, breakdown of the ocular-blood barrier, and autoimmunity all play a significant part. The involvement of Leptospira sp. is a well-known yet often inconsistent finding, and the latter two factors are likely the most important driver in this disease. Appaloosas have a yet undefined breed predisposition.3

Affected eyes have a wide range of morphologic appearances, but the following have been noted with regularity in this condition: lymphoplasmacytic uveitis with lymphoid follicle formation; lymphocytes and/or plasma cells within the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium; eosinophilic linear inclusions within the cytoplasm of nonpigmented ciliary body epithelial cells, amyloid; and the deposition of a cell-poor hyaline protein on the inner surface of the nonpigmented ciliary body epithelium.4 A wide range of non-specific secondary changes may be seen in affected eyes, including cataracts, anterior and posterior synechiae, iridal fibrovascular membranes, retinal degeneration and attachment, and optic neuritis.4

On a cellular level, the distribution of lymphocytes is characteristic of a TH1-like inflammatory response with a predominance of CD4 plus T cells and increased transcription of IL-2 and interferon gamma. Retinal autoantigens, including intra-photo receptor binding protein, cellular rectum aldehyde binding protein, recover in, and retinal S antigen have been demonstrated in experimental models and spontaneous cases of the ERU.4

The presence of corpora nigra (a normal structure in the eye of the horse which assists in filtering light coming into the globe) is useful in orienting horse eyes, as they are primarily found in the dorsal iris leaflet.

The formation of the JPC morphologic was a subject of spirited discussion. Due to the lack of significant inflammation, the term “uveitis” was not considered appropriate in this case. The combination of amyloid and crystalline inclusions within non-pigmented ciliary body epithelium in the first morphologic diagnosis above was made more out of convention than a shared pathogenesis. While references refer to the inclusions as “amyloid-like”13, amyloid is an extracellular protein, and ultrastructurally, many of these inclusions are present in the mitochondria in ciliary body epithelium. The true nature of these inclusions is yet to be determined. The second morphologic diagnosis of anterior Synechiae with drainage angle occlusion is likely the result of recurrent episodes of now-resolved inflammation and subsequent fibrosis within the drainage angle. While this change is certainly consistent with the contributor’s diagnosis of secondary glaucoma, we are unable to confirm this finding with the limited number of intraocular tissue available on the slide. While the contributor identified retinal atrophy (possibly from being able to evaluate the whole globe), the conference slides only contain peripheral retina, the evaluation of which, in the moderator’s (and JPC staff) experience, for atrophy is problematic at best.

References:

- Cooley PL, Wyman M, Kindig O. Pars plicata in equine recurrent uveitis. Vet Pathol 1990; 27:138-140.

- Deeg CA. Ocular immunology in equine recurrent uveitis. Vet Ophthalmol 2008; 11, Suppl.1,61-54.

- Dubielzig RR. The uvea. In: Dubielzig RR, Ketring KL, McLellan GJ, Albert DM, ed. Veterinary Ocular Pathology: A Comparative Review. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:245-322..

- Dubielzig RR, Render JA, Morreale RJ. Distinctive morphologic features of the ciliary body in equine recurrent uveitis. Vet Comp Ophtalmol 1997; 7:163-167.

- Frellstedt L. Equine recurrent uveitis: A clinical manifestation of leptospirosis. Equine Vet Educ 2009; 21:546-552.

- Hines MT. Immunologically mediated ocular disease in the horse. Vet Clin North Am Large Anim Pract 1984; 6:501-512.

- Kim, DY, Taylor HW, Eades SC, Cho DY. Systemic AL amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma in a horse. Vet Pathol 2005; 42(1):81-84.

- Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of domestic animals, Vol 1, 6th Philadelphia, USA: Elseviers Saunders; 2017:509-735.

- Østevik L, de Souza GA, Wien TN, Gunnes G, Sørby R. Characterization of amyloid in equine recurrent uveitis as AA amyloid. J Comp Path 2014; 151:228-233.

- Ostevik L, Gjermund Gunnes, de Souza GA, Wien TN, Sorby R. Nasal and ocular amyloidosis in a 15-year-old horse. Acta Vet Scand 2014; 56:50-59.

- Pearce JW, Galle LE, Kleiboeker SB, et al. Detection of Leptospira interrogans DNA and antigen in fixed equine eyes affected with end-stage equine recurrent uveitis. J Vet Diagn Invest 2007; 19:686-690.

- Romeike A, Brugmann M, Drommer W. Immunohistochemical studies in equine recurrent uveitis (ERU). Vet Pathol 1998; 35:515-526.

- Wilcock BP. Eye and ear. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of domestic animals, Vol 1, 5th Philadelphia, USA: Elseviers Saunders; 2007:459-552.

- Wogemeskell, M. A concise review of amyloidosis in animals. Vet Med Int 2012; Article is ID, 427296.