Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

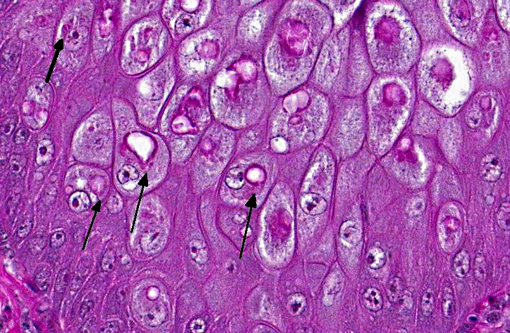

There is locally extensive, marked epithelial and epidermal hyperplasia of the conjunctiva and feathered skin. The epithelium is up to 8-10 times its normal thickness and has extensive serocellular crusting. There are foci of heterophilic infiltration and hemorrhage. Many keratinocytes have marked cytoplasmic vacuolation (ballooning degeneration) and many are expanded by 10-30 μm eosinophilic/red intracytoplasmic inclusions (Bollinger bodies). The dermis is moderately infiltrated by lymphocytes, macrophages and heterophils.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Avian or fowl pox are diseases caused by a variety or viruses of the genus Avipoxvirus, a member of the poxviridae. This DNA virus group has very large viral particles (250 to 300 nm). Avipoxvirus induces intracytoplasmic, lipophilic inclusion bodies, Bollinger bodies, in the epithelium of the integument. Their appearance is pathognomonic.3,9,10 The virus is recognized in more than 232 species of wild birds representing 23 orders, however, it is likely that many more bird species are susceptible to Avipoxvirus.(1)

Fowl pox is a slow spreading disease which may present in two forms: 1) the cutaneous form is characterized by the development of discrete nodular proliferative skin lesions on the non-feathered parts of the body, and 2) the diphtheritic form with fibrinonecrotic and proliferative lesions in the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract, mouth and esophagus. Flock mortality is usually low if the cutaneous form prevails, but it may be high with generalized infection, with the diphtheritic form, or when the disease is complicated by other infectious or poor environmental conditions.(1,3,9) In canaries and other finches, mortality can reach 80 to 100%.(1,3,9)

Avian pox is not of public health significance and it doesnt generally affect mammals.(9)

The mode of transmission is through virus carriers and contaminated environment. Mosquitoes and mites are the main vectors. Aerosols generated from infected birds, or the ingestion of contaminated food or water have also been implicated as a source of transmission.(10) The disease may have a seasonal incidence, occurring during late summer and autumn, which in some countries coincides with the peak of the mosquito season. The virus can survive in the vectors salivary glands for 2 to 8 weeks. Spread of the virus within a given bird population is triggered by close contact between birds and the formation of small traumatic lesions due to pecking on one another. During latent infection or after recovery from clinical disease, the virus is intermittently shed via the feces or the skin and feather quills.(3,9)

The clinical signs seen in the cutaneous form of pox are very characteristic, with formation of nodules that first appear as small white foci and then rapidly increase in size and become yellow. Initially there is formation of papules followed by vesicles and thickened areas. Adjacent lesions may coalesce and crust, acquiring a gray, or dark brown color. Later on, there is development of inflammation with hemorrhage and formation of a scab that sloughs off and leaves a pink scar.(3)

In the diphtheritic form, slightly elevated, white, opaque nodules develop in the mucous membranes. Nodules rapidly increase in size and often coalesce, becoming a yellow, cheesy, necrotic, pseudo-diphtheritic or diphtheritic membrane. The inflammation process may extend into the sinuses and also in the esophagus, pharynx and larynx resulting in respiratory disturbances.(9)

Histopathology usually reveals epithelial hyperplasia (in both diphtheritic and cutaneous forms), with cell swelling, associated inflammatory changes, and typical large, solid or ring-like, eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions known as Bollinger bodies.(3,9,10) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) may also reveal definite proof of Avipoxvirus infection, demonstrating the typical particles within inclusion bodies. Avipoxvirus identification may also be carried out by negative staining electron microscopy with 2% phosphotungstic acid (PTA) on infected cells.(10)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Conference participants briefly discussed the differential diagnosis for gross findings associated with the diptheritic form of avian pox, including Gallid herpesvirus-1 (infectious laryngotracheitis), Capillaria annulata or C. contorta, Trichomonas gallinae, Candida albicans, Aspergillus spp., and vitamin A deficiency. Rule outs for the cutaneous form include dermatophytosis (Trichophyton megninii or T. simii), papillomavirus and the mite Knemidokoptes gallinae.(3,4) These conditions can generally be differentiated microscopically; histochemical staining with giemsa highlights the prominent intracytoplasmic Bollinger bodies associated with avipoxvirus, while herpesviral infection results in intranuclear viral inclusions. Identification of yeast, hyphae or pseudohyphae (in cases of candidiasis or aspergillosis), arthrospores (dermatophytosis), trichomonads, nematode adults, larvae or eggs (capillariasis), arthropod segments (knemidokoptosis), or squamous metaplasia of glandular epithelia (vitamin A deficiency) is suggestive of one of the alternative etiologies enumerated above.(2,5,7-9,11)

Table 1: Select genera of the family Poxviridae.4,6

| Genus | Virus/Disease | Major Hosts |

| Orthopoxvirus | Vaccinia virus Buffalopox/Rabbitpox virus* | Numerous: cattle, buffalo, swine, rabbits |

| Cowpox* | Rodents (reservoir), cattle, cats, elephants, rhinos | |

| Camelpox | Camels | |

| Ectromelia (Mousepox) | Mice, voles | |

| Monkeypox* | NHPs, squirrels, anteaters | |

| Capripoxvirus | Goatpox | Goats, sheep |

| Sheeppox | Sheep, goats | |

| Lumpy skin disease virus | Cattle, cape buffalo | |

| Suispoxvirus | Swinepox virus | Swine (vector= Hematopinus suis) |

| Leporipoxvirus | Myxoma virus | Rabbits (Oryctolagus & Sylvilagus spp.) |

| Rabbit fibroma virus, Hare fibroma virus | Rabbits | |

| Squirrel fibroma virus | Grey and red squirrels | |

| Avipoxvirus | Fowlpox, canarypox, quailpox, etc | Chickens, turkeys, peacocks, etc. |

| Parapoxvirus | Caprine parapoxvirus (Orf; contagious ecthyma)* | Sheep, goats |

| Bovine parapox (bovine papular stomatitis virus)* | Cattle | |

| Pseudocowpox* | Cattle | |

| Sealpox* | Seals | |

| Parapoxvirus of red deer | Red deer | |

| Molluscipoxvirus | Molluscum contagiosum virus* | NHPs, birds, dogs, kangaroos, equids |

| Yatapoxvirus | Yabapox virus & tanapoxvirus* | NHPs |

| Unclassified | Squirrel poxvirus, fish (carp edema), horsepox |

References:

1. Bolte AL, et al. Avian host spectrum of avipoxviruses. Avian Pathology. 1999;28:415-432.

2. Charlton BR, Chin RP, Barnes HJ. Fungal infections. In: Saif YM, ed. Diseases of poultry. 12th ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 2008:1001-1003.

3. Gerlach H. Viral diseases. In: Harrison and Harrisons Clinical avian medicine and surgery. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1986:409-414.

4. Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Rakich PM. Skin and appendages. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. New York, NY: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:664-673.

5. Guy JS, Garcia M. Laryngotracheitis. In: Saif YM, ed. Diseases of poultry. 12th ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 2008:137-147.

6. Hargis AM, Ginn PE. The integument. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:1020-1024.

7. Hinkle NC, Hickle L. External parasites and poultry pests. In: Saif YM, ed. Diseases of poultry. 12th ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 2008:1015-1018.

8. McDougald LR. Histomoniasis (blackhead) and other protozoan diseases of the intestinal tract. In: Saif YM, ed. Diseases of poultry. 12th ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 2008:1100-1103.

9. Tripathy DN, Reed WM. Pox. In: Saif YM, ed. Diseases of poultry. 12th ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 2008:291-303.

10. Weli SC, Tryland M. Avipoxviruse: infection biology and their use as vaccine vectors. Virology Journal. 2011;8:49-63.

11. Yazwinski TA, Tucker CA. Nematodes and acanthocephalans. In: Saif YM, ed. Diseases of poultry. 12th ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 2008:1028-1029.