WSC 2023-2024 Conference 5, Case 1

Signalment:

3-year-old, female spayed domestic short hair, feline (Felis catus)

History:

This patient had a history of unspecified respiratory problems and presented to the referring veterinarian in an agonal state. Prior to presentation, the cat developed sudden breathing difficulties followed by collapse.

Gross Pathology:

Gross examination reveals a carcass with a body condition score of 4 out of 5, mild dehydration and mild autolysis. The lungs have a moderate, diffuse, cobblestone appearance and are meaty with patchy red to dark red discoloration. On section, a small amount of mucoid, pale yellow material can be expressed from many bronchioles. There is a large amount of this material in the bronchi and distal two thirds of the trachea.

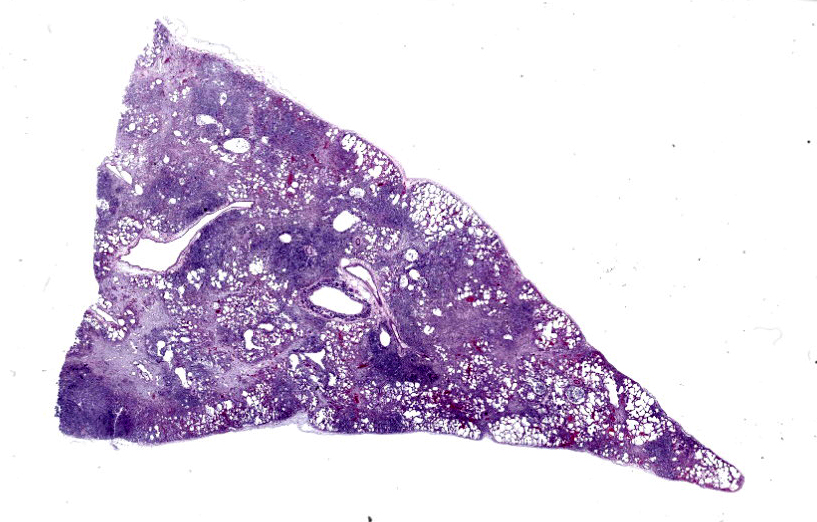

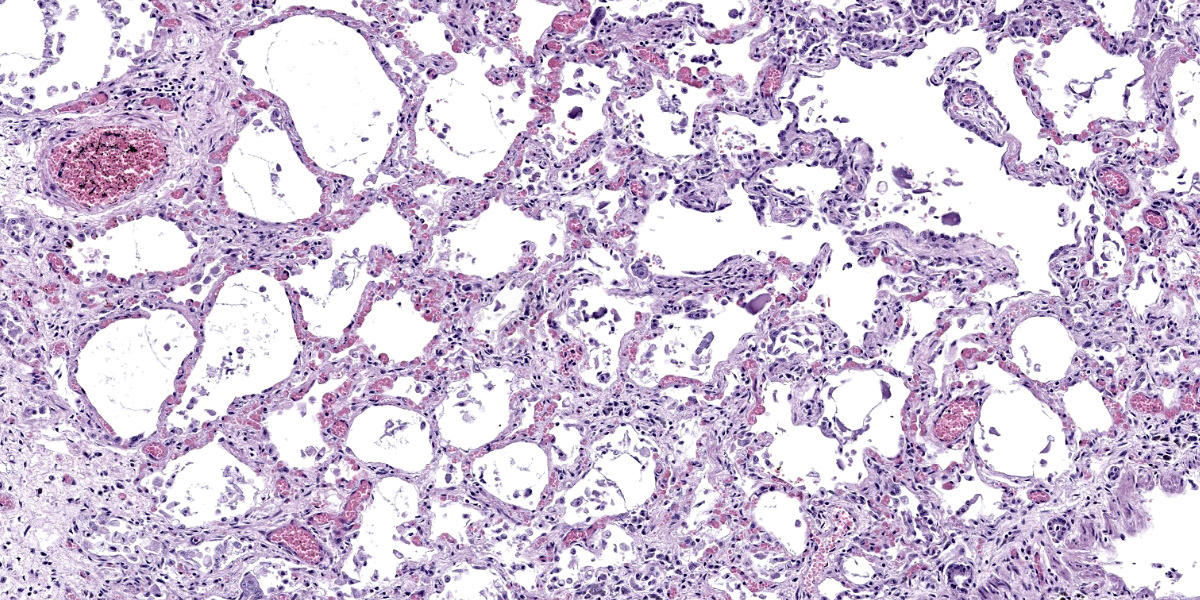

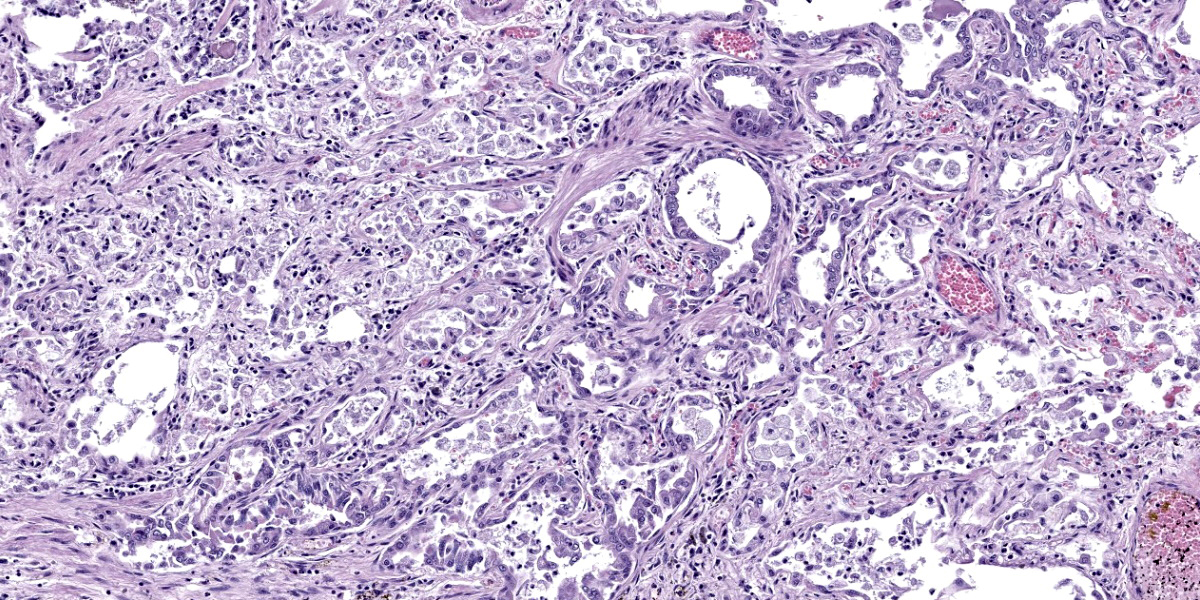

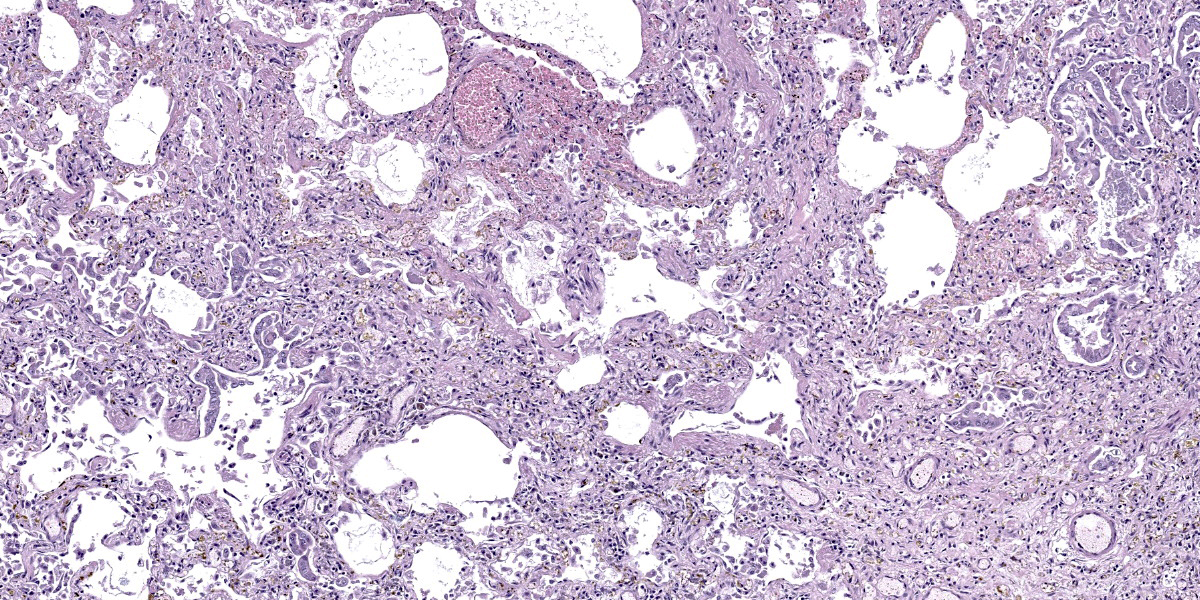

Microscopic Description:

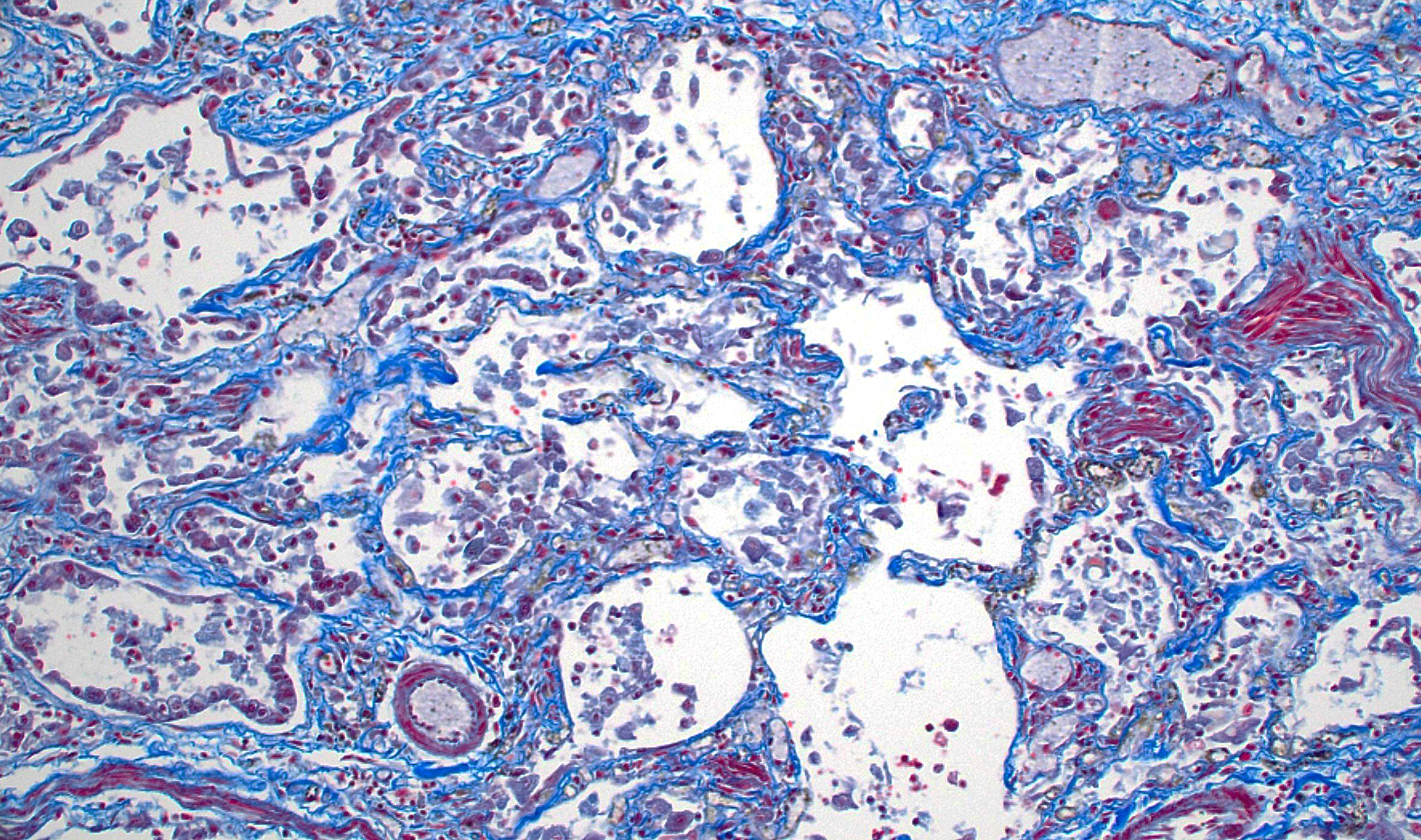

Lung: The pulmonary architecture is disrupted by widespread fibrosis affecting the axial interstitium and many alveolar septa, creating pseudolobulation with frequent multifocal alveolar emphysema (‘honeycombing’). Multiple alveolar septa are lined by pleomorphic, commonly low columnar epithelial cells with reactive nuclei (alveolar epithelial metaplasia) and there is type II pneumocyte hyperplasia. There are scattered foci of smooth muscle hyperplasia intermixed with the fibrous connective tissue. Variable cellular infiltrates, consisting mostly of neutrophils and macrophages, are present in alveoli rimming obliterated bronchioles. Bronchioles are filled with mucus and tend to be either denuded or lined by a mix of cuboidal and squamous epithelium.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung: Severe, chronic, bronchointerstitial pneumonia with marked alveolar septal and interstitial fibrosis, emphysema, alveolar epithelial columnar metaplasia, type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, and cuboidal to squamous metaplasia of bronchiolar epithelium.

Contributor’s Comment:

The histologic appearance of the lung is consistent with feline idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Key histologic features of this uncommon condition as seen here include: 1) interstitial fibrosis with foci of fibroblast/myofibroblast proliferation, 2) columnar metaplasia of alveolar epithelium with type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (in some cases, mucous cell metaplasia is also common, but not seen in our case) and 3) smooth muscle hyperplasia/metaplasia.1-3,5 This is similar to the histologic changes seen in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in humans.5 This condition typically affects middle to older aged cats, although it has also been reported in cats under three years of age.1-5 Presenting signs are largely respiratory related and include coughing, open mouth breathing, increased respiratory effort and rate, and respiratory distress.1-5 Prognosis is usually poor and most individuals pass away within a year of presenting with respiratory signs despite treatment with steroids, bronchodilators, antibiotics and diuretics.1-5 The cause for the condition is unknown, although a defect in type II pneumocyte development and function has been proposed.1,5

Contributing Institution:

Oregon State University

Corvallis, OR 97331

https://vetmed.oregonstate.edu/diagnostic

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Fibrosis, interstitial, diffuse, severe, with neutrophilic and histiocytic alveolitis, and smooth muscle and type II pneumocyte hyperplasia.

JPC Comment:

Feline idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (FIPF) is one of several pulmonary diseases of veterinary importance that are characterized by fibrosis of the alveolar septa. Others include pulmonary fibrosis of West Highland Terriers, canine pulmonary fibrosis disease of unknown etiology, and equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis, a helpfully named disease associated with equine herpesvirus-5.

As the contributor notes, the key histologic findings of FIPF include interstitial fibrosis with foci of fibroblasts or myofibroblasts, honeycombing of alveoli with alveolar epithelial metaplasia, and alveolar interstitial smooth muscle metaplasia.1 These changes occur without a significant interstitial inflammatory infiltrate. The expansion of alveolar septa by fibrous connective tissue and smooth muscle leads to decreased pulmonary compliance, and the resulting pattern of respiratory distress is typically inspiratory or mixed inspiratory/expiratory. This distinguishes FIPF clinically from the more common bronchial-centered disorders in cats, such as asthma and chronic bronchitis, which are characterized by expiratory distress.1

Definitive diagnosis of FIPF requires the demonstration of the previously described architectural and fibrous changes via histopathology. Published cases that include radiographic results report pronounced patchy to diffuse changes on thoracic radiographs, but the described changes are nonspecific and a mix of radiographic patterns has been described.1-3 Bronchioalveolar lavage and fine needle aspirates can be used to rule out infectious causes for the clinical signs, but are unable to rule in a diagnosis of FIPF.1

While ante-mortem pulmonary biopsy can be useful for definitive diagnosis, care should be taken as up to 24% of cats in one study had concomitant pulmonary neoplasia, typically in areas of marked fibrosis.1,4 This association is also seen in human cases of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and when sampled as part of ante-mortem biopsy, pulmonary malignancy may complicate recognition of the concurrent FIPF which is often the primary cause of respiratory symptoms.1,4

Standard empiric therapies for feline respiratory disease, such as corticosteroids, rarely result in clinical improvement of FIPF patients, and a robust understanding of the disease pathogenesis is needed before therapeutic targets can be identified. Future treatments are likely to be focused on pharmacologic modulation of fibroblast-pulmonary parenchymal cell interactions, including TGF-β antagonists, inhibition of collagen-synthesis enzymes, and matrix metalloproteinase activity enhancement.1

This week’s conference was moderated by MAJ Alicia Moreau, Chief of Education and Training and the Joint Pathology Center. MAJ Moreau discussed the terminology used to describe this condition in the veterinary literature. Of particular interest was the use of the term “alveolar epithelial metaplasia,” which is often used as a key histologic feature of this entity. Participants felt this term was inconsistently or rarely defined in the literature, but in practice is often used to mean type II pneumocyte hyperplasia. Similar inconsistencies were noted with the term “honeycombing,” which is defined differently depending on the source; however, most definitions contemplate confluent airspaces lined by cuboidal or hyperplastic epithelium and surrounded by fibrosis.

Conference participants felt that the defining histologic characteristic of this condition was the abundant fibrosis. Consequently, the JPC morphologic diagnosis leads with fibrosis while still acknowledging the mild inflammatory infiltrates present within the alveoli.

References:

- Cohn LA, Norris CR, Hawkins EC, et al. Identification and characterization of an idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-like condition in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2004; 18(5):632-41.

- Evola MG, Edmondson EF, Reichle JK, et al. Radiographic and histopathologic characteristics of pulmonary fibrosis in nine cats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2014; 55(2):133-140.

- Le Boedec K, Roady PJ, O'Brien RT. A case of atypical diffuse feline fibrotic lung disease. J Feline Med Surg. 2014; 16(10):858-863.

- Reinero C. Interstitial lung diseases in dogs and cats part I: the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Vet J. 2019; 243: 48-54.

- Williams K, Malarkey D, Cohn L, et al. Identification of spontaneous feline idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: morphology and ultrastructural evidence for a type II pneumocyte defect. Chest. 2004; 125(6): 2278-2288.