Conference 14, Case 1

Signalment:

9-year-old American Quarter Horse gelding (Equus caballus)

History:

This horse was acutely recumbent and depressed with severe colic, muscle fasciculations, and hyperhidrosis. A second horse from the same group had similar, more mild clinical signs, including depression and patchy sweating. A mule from the same pasture was found dead.

Gross Pathology:

Crown-rump length was 48.5 cm. No obvious gross abnormalities were seen within the examined organs.

Laboratory Results:

Phosphine gas was detected in the gastric contents of this horse and 3 of the 7 other horses in the same group.

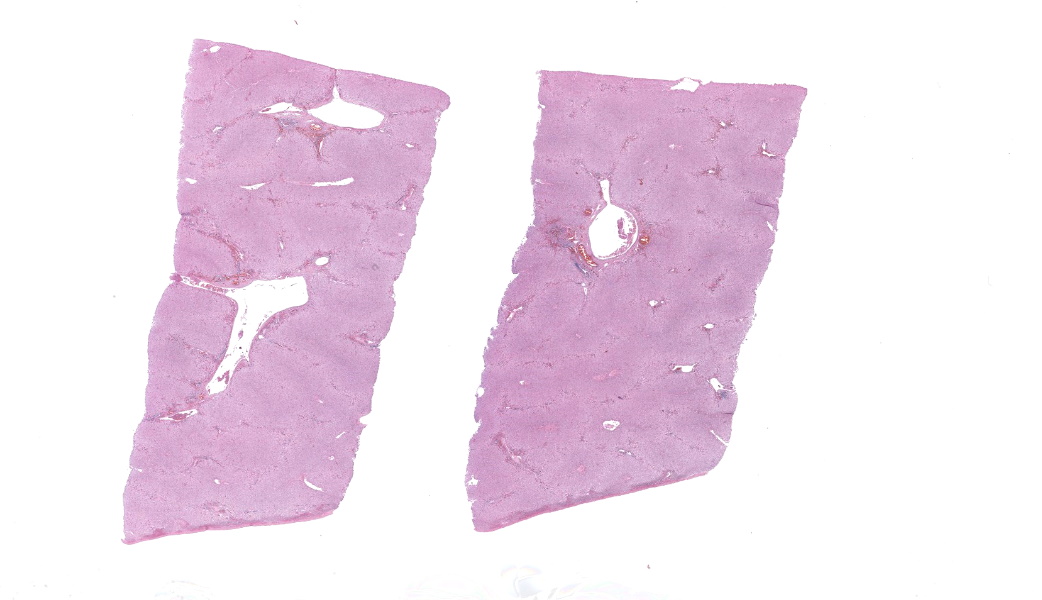

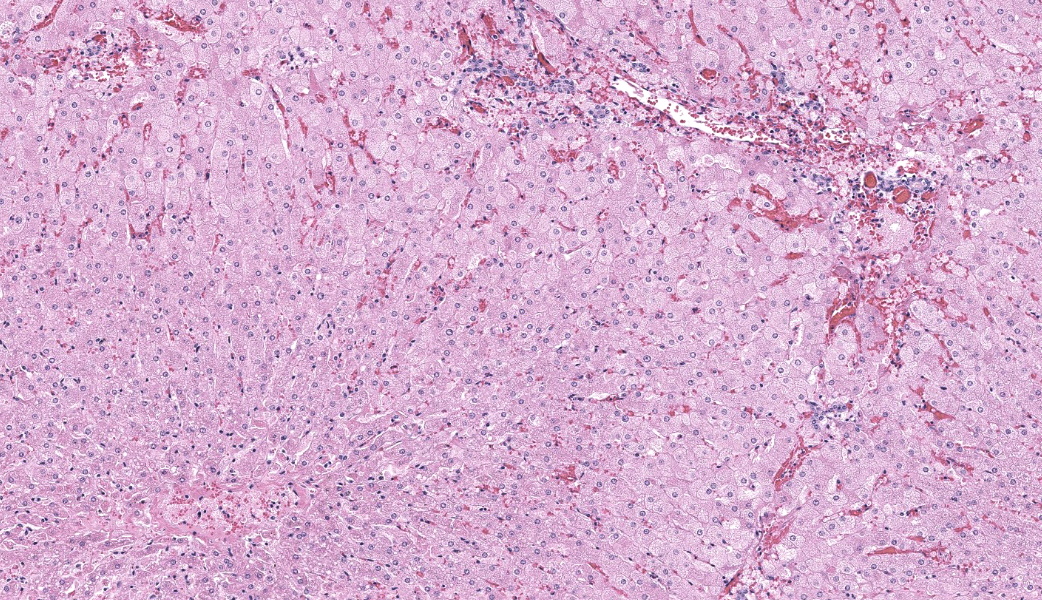

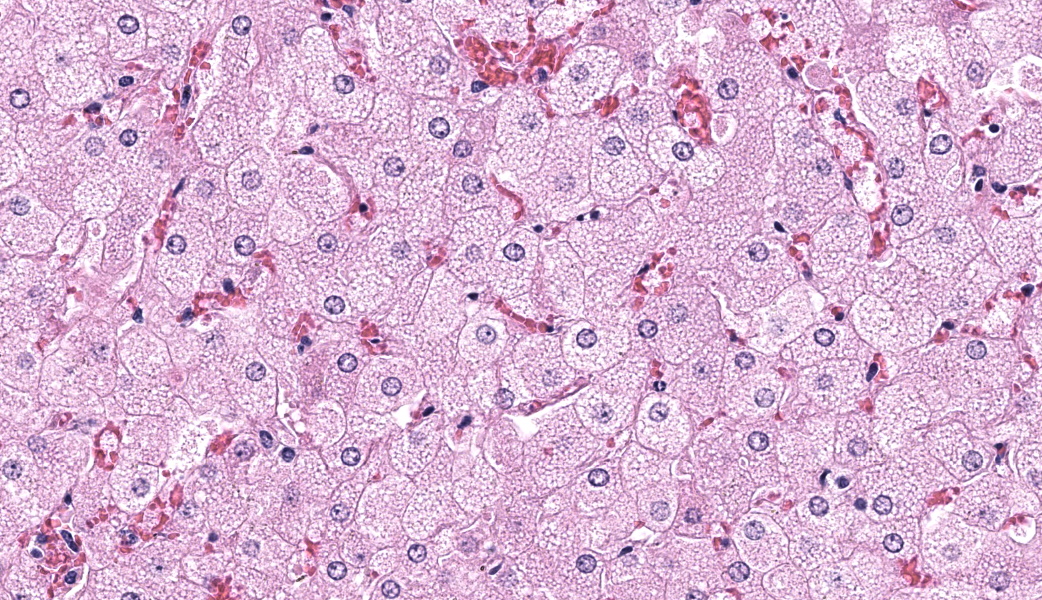

Microscopic Description:

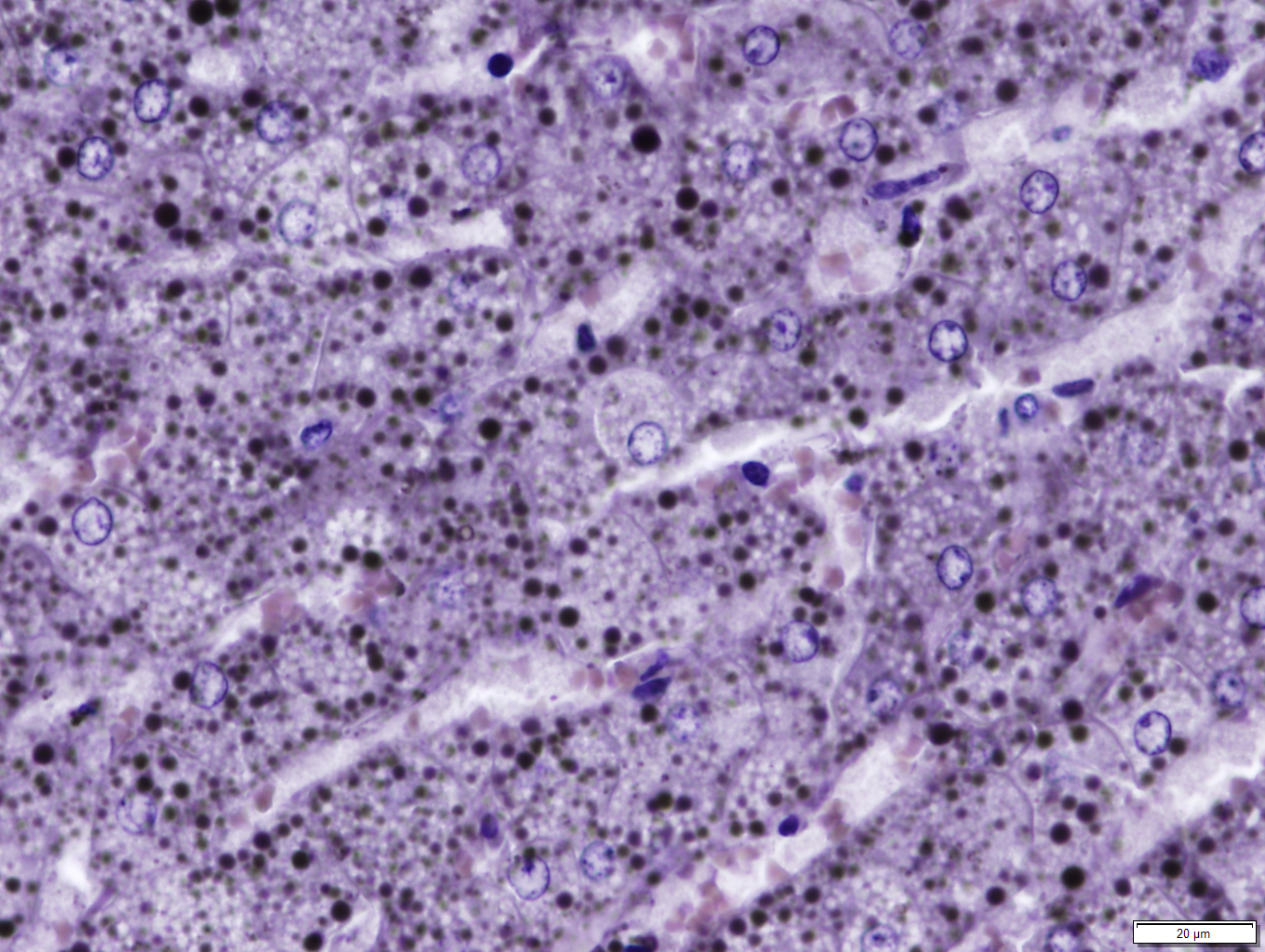

Liver: Diffusely, hepatocytes are moderately swollen and contain numerous small (~1µm) discrete to coalescing cytoplasmic vacuoles (microvesicular hepatopathy). Nuclei remain centrally located. Within the centrilobular interstitium, hepatocytes are occasionally individualized, rounded, shrunken, and/or hypereosinophilic with karyolysis (necrosis). There is mild, patchy periportal hemorrhage.

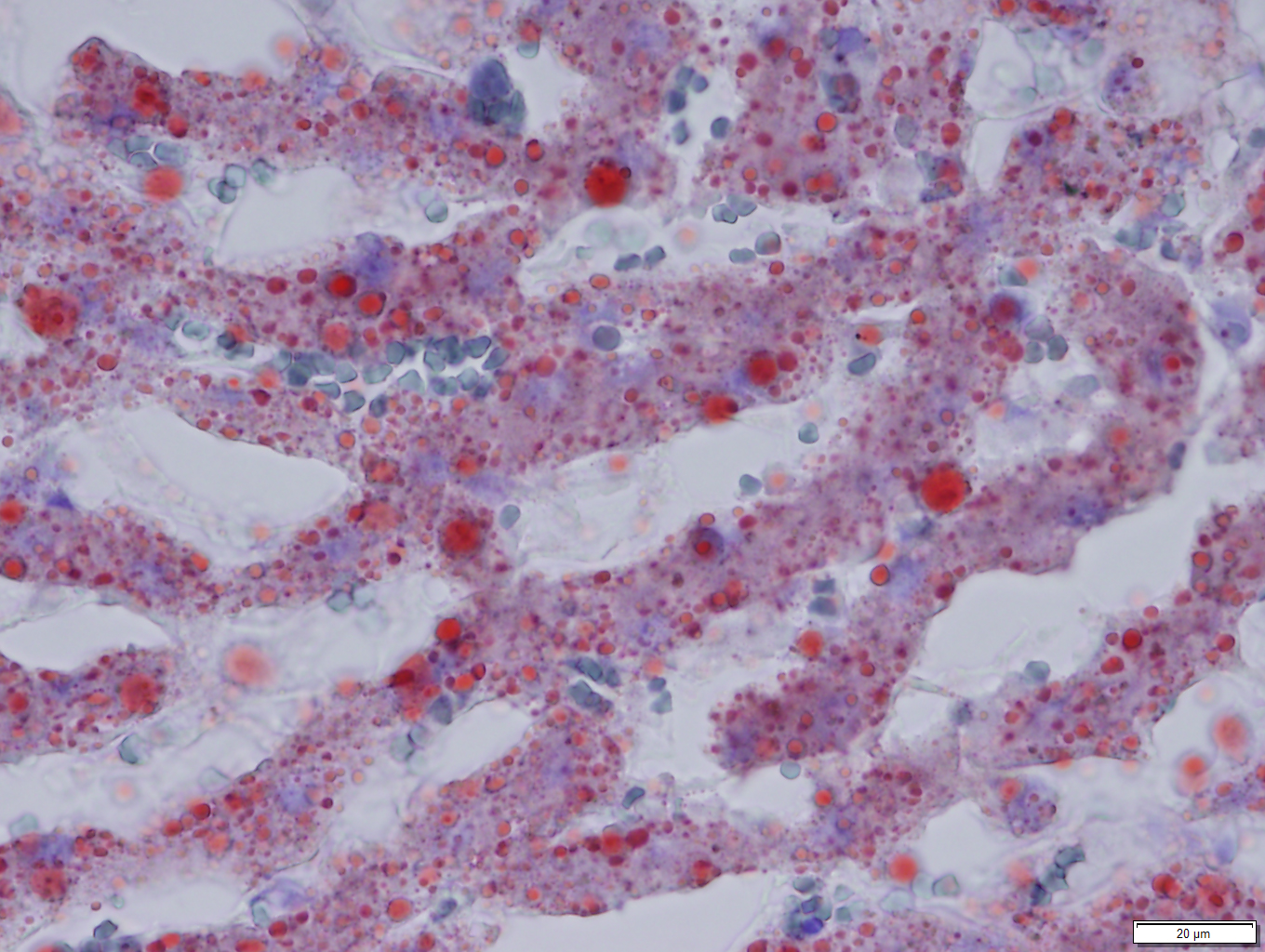

Special stains:

Osmium tetroxide post-fixation revealed prominent staining of microvesicular lesions, confirming the vacuoles as lipid droplets.

Oil Red O revealed prominent staining of microvesicular lesions, again confirming the vacuoles as lipid droplets.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Liver: Microvesicular hepatopathy, moderate, acute, diffuse, with mild centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis.

Contributor’s Comment:

Phosphine toxicosis was suspected based on recent use of grain-based zinc phosphide rodenticide to control a colony of black-tailed prairie dogs on a 200-hectare pasture. This suspicion was confirmed by the presence of phosphine gas in the stomach contents of this horse and 3 additional horses in the same group. Phosphine gas is a toxic metabolite of metallic phosphides, including zinc phosphide rodenticide and aluminum phosphide insecticide. It is readily produced in the acidic environment of the stomach and inhibits cytochrome C oxidase, thereby blocking mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and resulting in rapid energy depletion.1 Metallic phosphides pose a threat to a wide variety of non-target mammalian and avian species, and are particularly dangerous to horses and other equids which cannot vomit.

Documented lesions of phosphine toxicosis are largely nonspecific and include disseminated congestion and hemorrhage, pulmonary edema, inconsistent myocardial, renal, and/or CNS pathology and recently described microvesicular hepatic steatosis.2,3,4,5 Macrovesicular steatosis is seen in equine cases of longer duration, along with variable centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis.3 While macrovesicular hepatic steatosis is a relatively common and nonspecific lesion, microvesicular steatosis has a shorter list of differentials. Defined as multiple lipid vacuoles smaller in size than hepatocyte nuclei6, microvesicular steatosis is a feature of toxicants that inhibit fatty acid oxidation, including tetracycline, salicylates, hypoglycin A, and valporic acid, in addition to metallic phosphides.6

Phosphine gas is toxic to humans and poses a risk to medical professionals treating intoxicated patients.7 The smell of decaying fish in gastrointestinal contents, either due to phosphine gas itself or contaminants in the pesticide, should raise suspicion on postmortem examination; importantly, pathologists should take care not to inhale the odor in attempt to distinguish the gas. Detection of phosphine gas in gastric contents can be accomplished via reaction with sulfuric acid, which produces a color change that signals a positive result as a rapid, qualitative diagnostic assay.3 Gas-chromatography-mass spectrometry can be employed for confirmation.8

Contributing Institution:

University of Wyoming

Wyoming State Veterinary Laboratory

1174 Snowy Range Road

Laramie, WY 82070

JPC Diagnoses:

Liver: Hepatocellular lipidosis, microvesicular, acute, diffuse, severe.

JPC Comment:

Welcome to the second half of WSC 2025-2026! This fourteenth conference was moderated by one of our treasured regulars: Dr. Julie Engiles from the University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center! Although Dr. Engiles specializes in equine orthopedic pathology, the JPC is currently lacking equine bone cases for the WSC (the team is not-secretly hoping for more orthopedic case submissions for next year, hint, hint). As such, she led participants through an excellent equine-focused, “squishy tissue” conference.

Discussion of this first case, never seen before in the WSC, covered the ins and outs of phosphine gas poisoning and other potential differentials for acute hepatotoxins in horses. The pattern of lesion distribution in this case was, unlike most toxins that whack the liver, not focused predominantly on centrilobular hepatocytes. Many hepatotoxins are metabolized to their toxic forms by CP450 in centrilobular regions, hence why those cells end up predominantly affected. Centrilobular hepatocytes are already living on the razor’s edge of hypoxia as it is, they don’t need much to be pushed over that edge. Few toxins, however, such as phosphorus, microcystin, and phosphine gas, do not need to be metabolized to cause serious damage. Instead, they are so directly toxic that they affect whatever they come across first. In the liver, this is the periportal areas, as those are the sites of first contact in the liver for products from systemic circulation.

Other differentials for acute hepatic necrosis in horses include equine parvovirus (Theiler’s disease) and the newly described equine hepacivirus. This flavivrus is closely related to human hepatitis C virus and is currently being looked at as a potential model for Hep C studies.9

There are two main forms of phosphides that are globally available and commonly used as pesticides: aluminum phosphide (AlP) and zinc phosphide (ZnP). AlP is generally considered the more volatile of the two. It reacts violently and exothermically with any moisture/acid it comes into contact with to create highly toxic, flammable, and often spontaneously igniting phosphine gas (PH3).6 This reaction is what makes it such a potent fumigant, but also makes it extremely hazardous. It is most commonly utilized in pellet form for grain fumigation, stored food protection, and large-scale pest control. Despite its risks, it is still the most widely utilized fumigant for stored grains.1 Ingestion is the most common method of exposure in humans and animals, followed by inhalation and absorption, respectively.6 Most case reports of phosphine poisoning are from India, with many reports also from Iran, Sri Lanka, Morocco, and numerous “developed” countries.6 As recently as 2022, there was an incident of accidental phosphine gas poisoning in Delhi, where two persons died of phosphine gas exposure after sleeping in a warehouse containing AlP.12

ZnP, on the other hand, primarily reacts with acids rather than just any form of moisture like AlP does, enabling its use as a common bait rodenticide. As with any other form of bait rodenticide, it is not uncommon for other animals that are not the intended target to ingest the poison and end up dead. Upon ingestion by

an animal, the ZnP reacts with hydrochloric acid in the stomach to produce lethal phosphine gas that is rapidly absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract, leading to systemic toxic effects that can manifest as acute, severe cardiac arrhythmias, shock, acidosis, hepatic lipidosis (as in this case), seizures, and/or pulmonary edema.1,6

In addition to directly corrosive actions, phosphine is a potent metabolic poison that functions similarly to cyanide, disrupting cellular energy production by targeting mitochondria and inhibiting cytochrome C oxidase.1,2,6 The electron transport chain, the major producer of ATP via oxidative phosphorylation and a process in which cytochrome C oxidase is a key player, occurs on the inner mitochondrial membrane. Following their production via the Kreb’s cycle, NADH molecules enter the transport chain and donate electrons to NADH dehydrogenase (also known as complex I). From here, the electrons are passed down a series of subsequent complexes like a relay race that ultimately produce a proton gradient across the mitochondrial membrane. Once an electron reaches complex IV (also known as cytochrome C oxidase), it is combined with an oxygen molecule and protons to form water, making oxygen the final electron acceptor and enabling the continued flow of the transport chain. The resultant proton gradient powers ATP synthase which, as protons flow back into the mitochondrial matrix, converts ADP to ATP in large quantities for use in energy-driven cellular functions. Basically, if cytochrome C oxidase is unable to do its job, electrons can't reach oxygen, which causes the chain to back up with “stuck” electrons, halting proton pumping, stopping ATP synthesis, and severely depleting cellular energy, which eventually leads to cell death. This effect is particularly potent in high-energy organs like the heart, lungs, liver, and brain.

As noted by the contributor, a "rotting fish" or "garlic" smell may accompany phosphine gas at autopsy. While pure PH3 gas is odorless, the fishy smell associated with phosphine gas results from common contaminants in the gas, primarily diphosphane (P2H4) or other organic phosphine compounds. Either way, sniffing dead bodies to try and figure out, “What’s that smell?” is strongly ill-advised.

References:

- Alzahrani SM, Ebert PR. Pesticidal Toxicity of Phosphine and Its Interaction with Other Pest Control Treatments. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2023;45(3):2461-2473

- Bumbrah GS, Krishan K, Kanchan T, Sharma M, Sodhi GS. Phosphide poisoning: a review of literature. Forensic science international. 2012 Jan 10;214(1-3):1-6.

- Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals.6th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2016:273–278.

- Drolet R, Laverty S, Braselton WE, Lord N. Zinc phosphide poisoning in a horse. Equine Veterinary Journal. 1996;28(2):161-2.

- Fox JH, Porter BF, Easterwood L, Hildenbrand JR, Hélie P, Smylie J, O’Toole D. Acute hepatic steatosis: a helpful diagnostic feature in metallic phosphide–poisoned horses. JVDI. 2018;30(2):280-5.

- Gurjar M, Baronia AK, Azim A, Sharma K. Managing aluminum phosphide poisonings. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4(3):378-84.

- Nagy AL, Bolfa P, Mihaiu M, Catoi C, Oros A, Taulescu M, Tabaran F. Intentional fatal metallic phosphide poisoning in a dog—a case report. BMC Veterinary Research. 2015;11(1):158.

- Olivares CP, Martínez RR, Daba MM, Thomsen JL. Zinc phosphide poisoning in a mare. Veterinaria México. 2002;33(3):343-6.

- Pacchiarotti G, Nardini R, Scicluna MT. Equine Hepacivirus: A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis of Serological and Biomolecular Prevalence and a Phylogenetic Update. Animals (Basel). 2022;12(19):2486.

- Plumlee KH. Pesticide toxicosis in the horse. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2001;17:491–500.

- Robison WH, Hilton HW. Gas chromatography of phosphine derived from zinc phosphide in sugarcane. J Agric Food Chem. 1971;19:875–878.

- Singh R, et al. Mysterious death due to accidental inhalation of phosphine – A unique case study. Forensic Science International: Reports. 2022;5:100264.