Signalment:

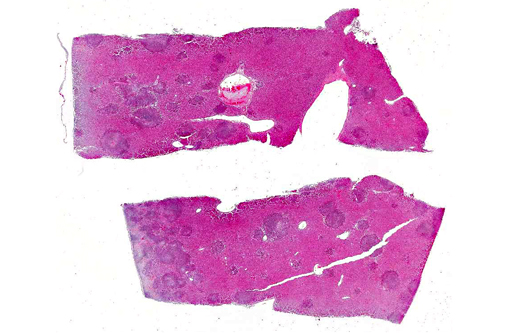

The next day, ultrasonic examination of the abdomen was made without proper results, so a laparotomy was performed. Within the abdomen there was ascites and severe multifocal necrotizing hepatitis, so a biopsy of the liver was taken. One day after the surgery the ring-tailed lemur was found dead in his cage.

Gross Description:

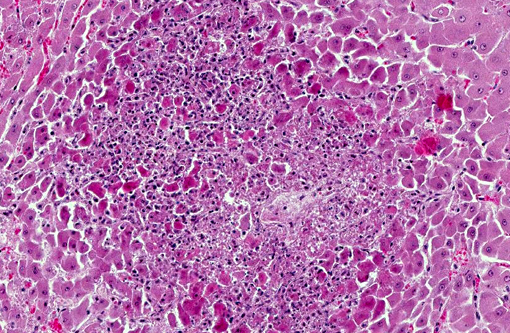

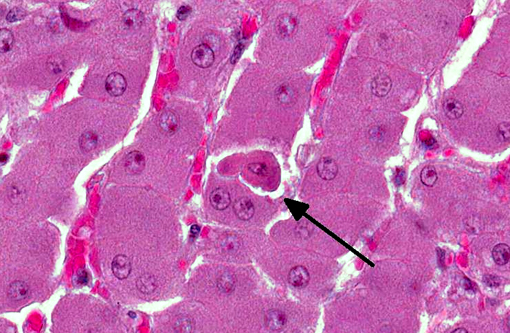

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Listeria monocytogenes was isolated from heart, lung, liver, spleen, kidney and central nervous system by bacteriological culture and confirmed by PCR.

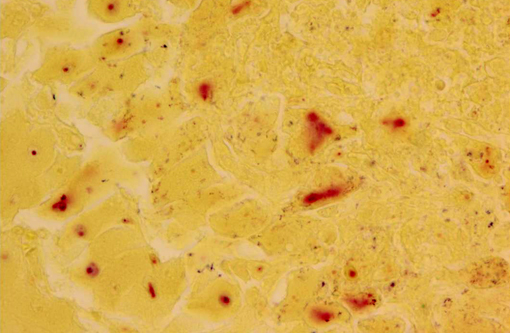

Immunohistochemistry using a polyclonal anti-Listeria monocytogenes-antibody revealed a positive reaction in liver, gallbladder, spleen, kidney, urinary bladder, large and small intestine, mesentery, pancreas, palatine tonsil, mesenteric lymph nodes and periorchium.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The disease is caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a facultative anaerobic, gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium which has the ability to invade cells and duplicate in the cytoplasm. Listeria monocytogenes is a ubiquitous pathogen; it is found in the natural microbial flora in ruminants, in the feces of birds and wild animals and it persists in the environment as a saprophyte, especially on decaying vegetation, such as inadequately soured silage. Listeria monocytogenes is known to cause three different clinical presentations. The cerebral form, with meningitis and encephalitis, is the most common in sheep. The pregnancy-associated form leads to stillbirths, abortion and premature birth. The third form is the septicemic form. Most cases of listeriosis remain clinically silent in healthy individuals.

Relatively few cases of listeriosis are reported in nonhuman primates (NHP) and there are no case reports in ring-tailed lemurs. Most of the reported incidences in NHP are accompanied by reproductive failure with abortion, stillbirth or neonatal death due to septicemia or cerebral complications.(1,6,11) There is one report of a free-living guereza in Kenya with similar pathologic findings to this case.(8)

The severe nature and rapid progression of the disease in the present case could be secondary to immune suppression, as lymphoid depletion is noted in multiple lymph nodes throughout the body.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

There is evidence that Listeria localizes to the ruminant brainstem via retrograde axonal migration along cranial nerve branches after crossing the oral epithelium, with potential spread into more rostral brain regions by intracerebral axonal migration. This is in contrast to human CNS infections where a hematogenous route is hypothesized.(3) It has also been suggested that E-cadherin (expressed by oral epithelium and Schwann cells) could bind internalin on the surface of Listeria to facilitate entry into the brainstem, however this has not yet been demonstrated.(3,4) Listerial abortions in ruminants occur during the last trimester of pregnancy with fetal infection or septicemia caused by hematogenous spread from the placenta. If the dam is infected at the beginning of the last trimester, there is rapid fetal infection and abortion with only mild maternal disease. If the infection occurs closer to parturition, dystocia with severe metritis, placentitis and septicemia are more likely.(10)

Histologic lesions of listeriosis are typically characterized by necrosis with a mild neutrophilic infiltrate.(8) Conference participants explored several potential differential diagnoses for necrotizing hepatitis in a NHP, briefly discussing Francisella tularensis, Clostridium piliforme and alphaherpesviruses. Hepatic conditions specifically reported in lemurs include cirrhosis, hemochromatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.(5,8)

References:

2. Cline JM, Brignolo L, Ford EW. Urogenital system. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T, eds. 2nd ed. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2012:524-525.

3. Disson O, Lecuit M. Targeting of the central nervous system by Listeria monocytogenes. Virulence. 2012;3(2):213-221.Â

4. Heldstab A, R+�-+edi D. Listeriosis in an adult female chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes). J Comp Pathol. 1982;92(4):609-612.Â

5. Fairley RA, Pesavento PA, Clark RG. Listeria monocytogenes infection of the alimentary tract (enteric listeriosis) of sheep in New Zealand. J Comp Path. 2012;146(4)308-313.

6. Glenn KM, Campbell JL, Rotstein D, Williams CV. Retrospective evaluation of the incidence and severity of hemosiderosis in a large captive lemur population. Am J Primatol. 2006;68(4):369-81.Â

7. Heldstab A, R+�-+edi D. Listeriosis in an adult female chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes). J Comp Pathol. 1982;92(4):609-612.Â

8. Lemoy MJ, Lopes DA, Reader JR, Westworth DR, Tarara RP. Meningoencephalitis due to Listeria monocytogenes in a pregnant rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Comp Med. 2012;62(5):443-447.Â

9. Kock ND, Kock RA, Wambua E, et al. Listeriosis in a free-ranging colobus monkey (Colobus guerezacaudatus) in Kenya. Vet Rec. 2003;152(5):141-142.

10. Nemeth NM, Blas-Machado U, Cazzini P, et al. Well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma in a ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta). J Comp Pathol. 2013;148(2-3):283-287.

11. Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:492-493.

12. Simmons J, Gibson S. Bacterial and mycotic diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T, eds. 2nd ed. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2012:105-172.Â