CASE IV:

Signalment:

9 year old, Male, Canine; Miniature Schnauzer (Canis lupus familiaris)

History:

Presumed acute abdomen. Chronic cryptorchid. Some feminization. Two abdominal masses that communicated were resected. One was at the base of the right kidney. The second seemed to be a prostatic cyst, markedly distended with exudate.

Gross Pathology:

None submitted.

Laboratory Results:

None submitted.

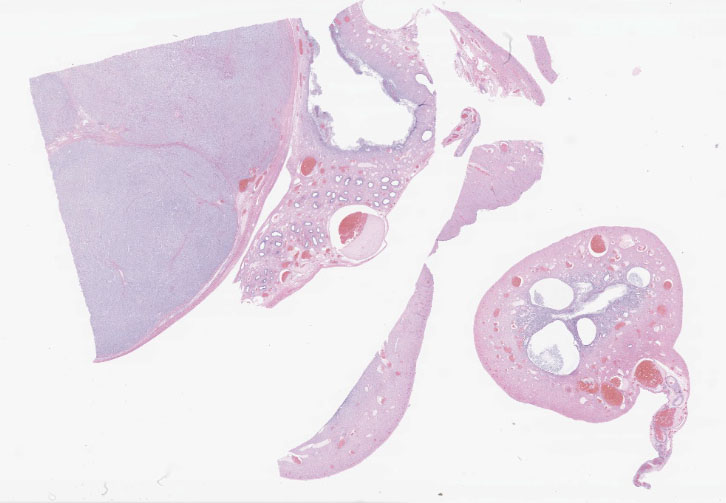

Histopathological Description:

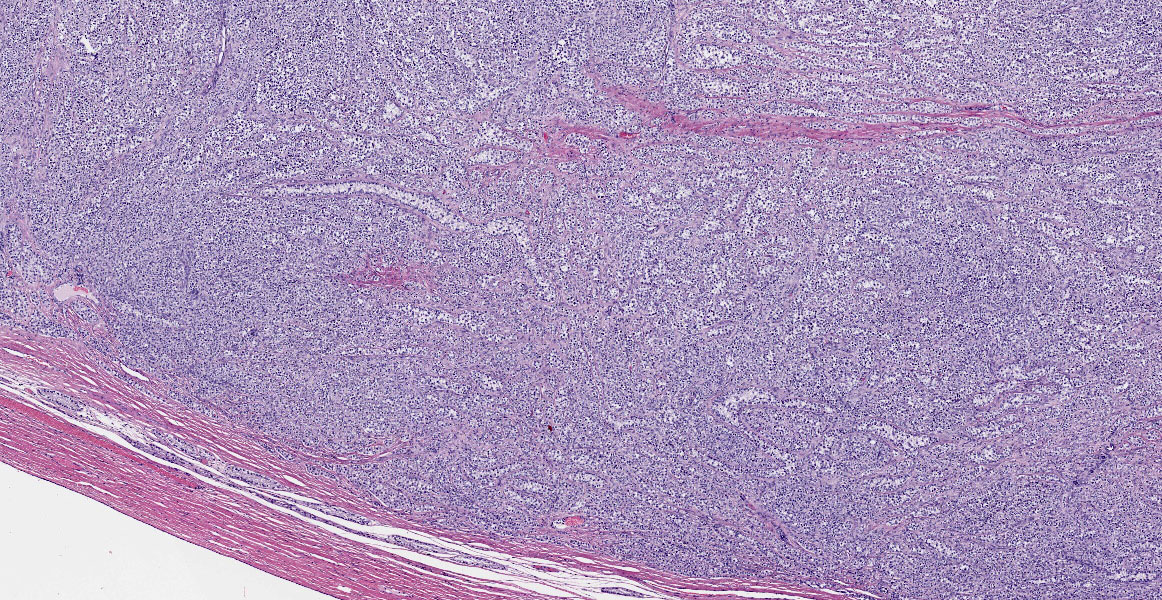

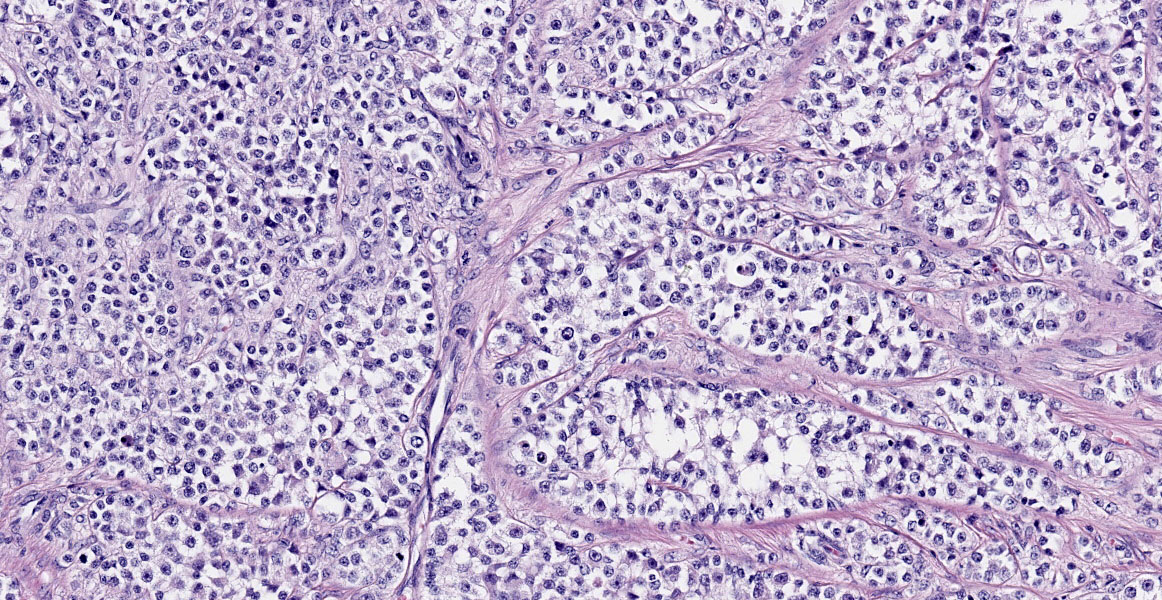

Testis:

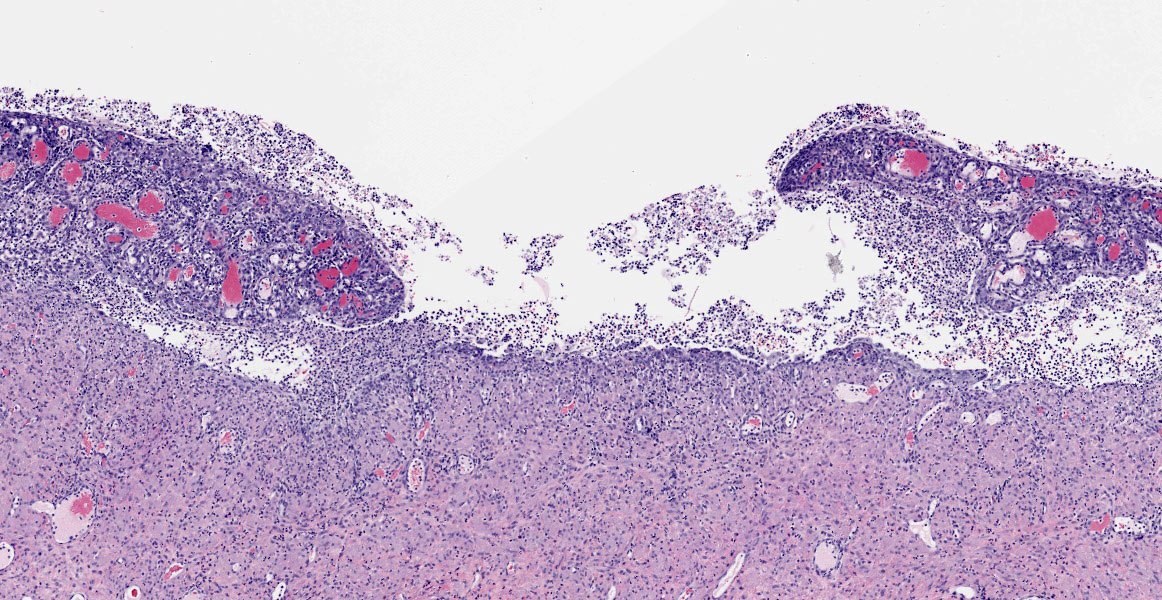

Blood vessels in the pampiniform plexus are moderately dilated. The testis is widely effaced by a highly cellular, nonencapsulated, multilobulated neoplasm composed of polyhedral cells arranged in tubules, islands, and cords separated and surrounded by dense bands of fibrous connective tissue. The neoplastic cells have moderate amounts of pale eosinophilic, variably foamy (lipid droplets) cytoplasm with indistinct cell margins and have a round to oval nucleus with coarse chromatin and up to two distinct nucleoli. The neoplastic cells occasionally palisade along the basement membrane of the tubules. Cellular and nuclear pleomorphism are mild. Mitotic figures are rare.

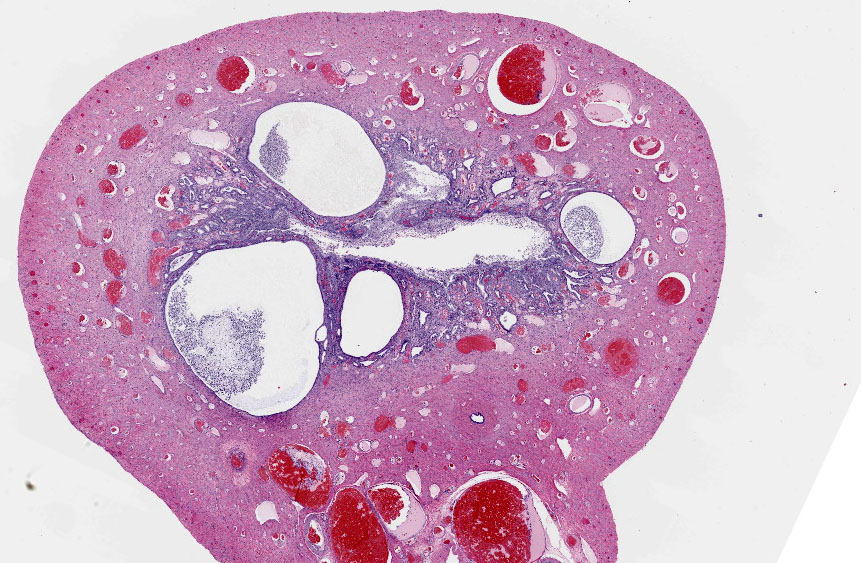

Uterus:

Adjacent to the testis, partially within and expanding the tunica albuginea, possibly into the tunica vaginalis, and also representing the separate tissue specimen, there is a smooth muscle lined tubular structure with a lumen lined by cuboidal to low columnar epithelial cells and with glandular structures within submucosal stroma, consistent with uterus. Within the lumen, infiltrating the stroma, and within multifocal variably dilated glands, there are neutrophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and foamy pale eosinophilic fibrillar material. There are areas of squamous metaplasia and erosion.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Testis: Sertoli cell tumor

Uterus: Uterus with pyometra/endometritis

Condition: Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome

Contributor's Comment:

The most common testicular tumors in dogs are: seminomas, interstitial cell tumors (Leydig cell tumors), Sertoli cell tumors, and mixed germ cell-stromal tumors. Cryptorchidism is associated with the development of seminomas, Sertoli cell tumors, and mixed germ cell-stromal tumors.1,2 Sertoli cell tumors most commonly occur in the right testis1 which is also more commonly cryptorchid than the left testis. The most common clinical signs/lesions associated with Sertoli cell tumors are gynecomastia, behavior changes,

alopecia, and bone marrow suppression.1,6 Sertoli cell tumors can be hormonally active and secrete hormones including Estrodiol 17B6 but not all patients with signs of feminization have elevated estrogen levels.1 The most common age at presentation is 10 years old, however, patients with tumors in a cryptorchid testis may present at a younger age.6 Grossly, Sertoli cell tumors are firm (due to abundant fibrous connective tissue within the mass), demarcated, variably nodular masses that can grow to very large size.1 The majority of Sertoli cell tumors are benign neoplasms1 but malignant forms can occur and may be more common in a retained testis. Histologically, intratubular and diffuse forms occur.1 Miniature Schnauzer dogs a predisposed to Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome presenting with cryptorchidism (approximately 50% cases)5, Sertoli Cell Tumor, and pyometra1, as seen in this case.

Sexual differentiation in dogs occurs in 3 consecutive events- chromosomal sex determination at fertilization, gonodal sex development (in utero), and phenotypic sexual determination.3,9 Testicular development in males requires Müllerian Inhibiting Substance (MIS) resulting in Müllerian duct regression and testosterone resulting in development of the vas deferens and epididymides.3 Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (PMDS) is considered a phenotypic sex abnormality or disorder of sexual development (DSD) and is also a type of male pseudohermaphroditism.9 Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome occurs in Miniature Schnauzers1 and other less commonly reported dog breeds5,9 and may rarely occur in cats. PMDS is due to a defect in production or function of MIS or mutated MIS receptor. A transition mutation resulting in a dysfunctional MIS receptor is the cause of the autosomal recessive condition in minature Schnauzers.7 The affected males have a normal male karyotype and male gonads, but also have a uterine body, uterine tubes, and cranial vagina.9

Pyometra is either acute or chronic inflammation of the uterus resulting in a purulent exudation. It can be open (open cervix with secondary bacterial infection) or closed and aseptic. Male patients with PMDS have no cervix or caudal vagina so the pyometra is aseptic and may at least in part be due to failure of drainage of luminal fluids secreted by variably dilated endometrial glands. Hormonal influence from a functional Sertoli cell tumor and variable cystic endometrial hyperplasia can contribute to the pyometra as well.

Contributing Institution:

Marshfield Vet Lab

1000 N. Oak Avenue

Marshfield WI 54449

Wennerdahl.laura@marshfieldclinic.org

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Testis: Sertoli cell tumor.

2. Uterus: Persistent paramesonephric duct, with marked suppurative endometritis and cystic endometrial hyperplasia.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a concise review male sexual development, factors associated with the development of the Persistent Müllerian Duct syndrome (PMDS), and sequela often associated with this disorder of sexual development (DSD), including testicular tumors and cryptorchidism, both of which were a subject of discussion during 21-22 WSC 14, case 1.

PMDS was first described as a rare form of male pseudohermaphroditism characterized by the presence of Müllerian Duct derivatives in humans by Nilson in 1939.8 Canine PMDS was first reported in 1976 by Brown, Bure, and McEntee, who described three cases of male pseudohermaphroditism and cryptorchidism miniature schnauzers.10 Although this XY disorder of sexual development (DSD) is most prevalent miniature schnauzers, it has since been reported other canine breeds, cats, cattle, goats, and a beluga whale.4,11

PMDS may arise due to either lack of anti-Müllerian hormone or a faulty receptor. In miniature schnauzers, PMDS is most commonly attributed to a cytosine to thymine nonsense autosomal recessive mutation in exon 3 of the gene encoding the anti-Müllerian hormone type II receptor (AMHR2).7,10 Homozygous dogs therefore lack functional receptors for anti-Müllerian hormone, resulting in failure of Müllerian duct regression and the formation of derivatives such as oviducts, uterus, cervix, and a cranial vagina, which may insert into the prostate. However, these female reproductive tract structures are internal and the dog exhibits a male phenotype.10

As noted by the contributor, approximately 50% of cases are either uni- or bilaterally cryptorchid. Despite being fertile, unilateral cryptorchid males are generally removed from the breeding pool. However, hetero- and homozygous female carriers, in addition to the remaining 50% of homozygous males with normal descended testicles are fertile.10

A 2018 study10 investigating the prevalence of the AMHR2 mutation in miniature schnauzers found 1.9% of 216 randomized samples were homozygous for the AMHR2 mutation, while 27.3% (n=59) were heterozygous. However, it is worth noting all the DNA samples used in this study were obtained from a single regional laboratory and may therefore reflect prevalence in a single geographic region rather than amongst the breed as a whole.10

PMDS is associated with significant morbidities, including increased risk of testicular tumors in cryptorchid males, as well as pyometra, both of which are demonstrated in this case. Additional pathologic conditions associated with PMDS include hydrometra, urinary tract infections, and prostatitis. Responsible breeding programs are therefore desirable in regard to the prevention of whelping additional puppies affected by PMDS. However, implementation of this concept would be a challenge given 100% of female and heterozygous males and approximately 50% of homozygous males are phenotypically normal. Therefore, development of a commercially available test for the AMHR2 mutation may be beneficial for the future of this breed.10

References:

1. Agnew DW, MacLachlan NJ. Tumors of the genital system. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals, 5th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2017:706-711.

2. Liao AT, Chu PY, Yeh LS, et al. A 12-Year Retrospective Study of Canine Testicular Tumors. J Vet Med Sci 2009 Jul; 71(7):919-23.

3. Meyers-Wallen VN. Genetics of Sexual Differentiation in Dogs and Cats. J Repr and Fert. 1993 Feb; 47:441-52.

4. Nogueira DM, Armada JLA, Penedo DM, Tannouz VGS, Meyers-Wallen VN. Persistent Mullerian duct Syndrome in a Brazilian miniature schnauzer dog. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2019;91(2):e20180752

5. Park EJ, Lee SH, Jo YK, et al. Coincidence of Persistent Mullerian Duct Syndrome and Testicular Tumors in Dogs. BMC Veterinary Research 2017; 13:156.

6. Post K and Kilborn S. Canine Sertoli Cell Tumor: A Medical Records Search and Literature Review. Can Vet J 1987 Jul; 28(7):427-431.

7. Pujar S, Meyers-Wallen VN. A Molecular Diagnostic Test for Persistent Mullerian Duct Syndrome in Miniature Schnauzer Dogs. Sex Dev 2009; 3:326-328.

8. Ren X, Wu D, Gong C. Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome: A case report and review. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14(6):5779-5784.

9. Silva P, Uscategui RA, Gatto IR, et al. Evidence of Persistent Mullerian Duct Syndrome in a Yorkshire Terrier. Rev Colomb Cience Pecu 2018; 31(4):315-319.

10. Smit MM, Ekenstedt KJ, Minor KM, Lim CK, Leegwater P, Furrow E. Prevalence of the AMHR2 mutation in Miniature Schnauzers and genetic investigation of a Belgian Malinois with persistent Müllerian duct syndrome. Reprod Domest Anim. 2018;53(2):371-376.

11. Stimmelmayr R, Ferrer T, Rotstein DS. Persistent Mü̈llerian duct syndrome in a beluga whale Delphinapterus leucas. Dis Aquat Organ. 2019;136(3):273-278.