CASE II: 14-699 (JPC 4074325)

Signalment:

3 y/o, female entire, German shepherd, Canis lupus familiaris (canine)

History:

This dog presented with a left hindlimb lameness, and a three week history of hesitancy to jump following a successful mating, and began a course of Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid antibiotics and Tramadol. Assessment at a referral practice the following day showed no evidence of hindlimb lameness, instead pain in the L2-L3 region, which was confirmed radiographically as a benign lucency, considered most likely an old discospondylitis lesion or Schmorl's node. Aspergillus antibody titers performed at the time were negative. In the subsequent two weeks the dog became anorexic, developed marked pain in both the lumbar and cervical spine which was refractory to multimodal analgesia, and was unable to bear weight on its forelimbs. The dog was euthanized and submitted for a complete post mortem examination.

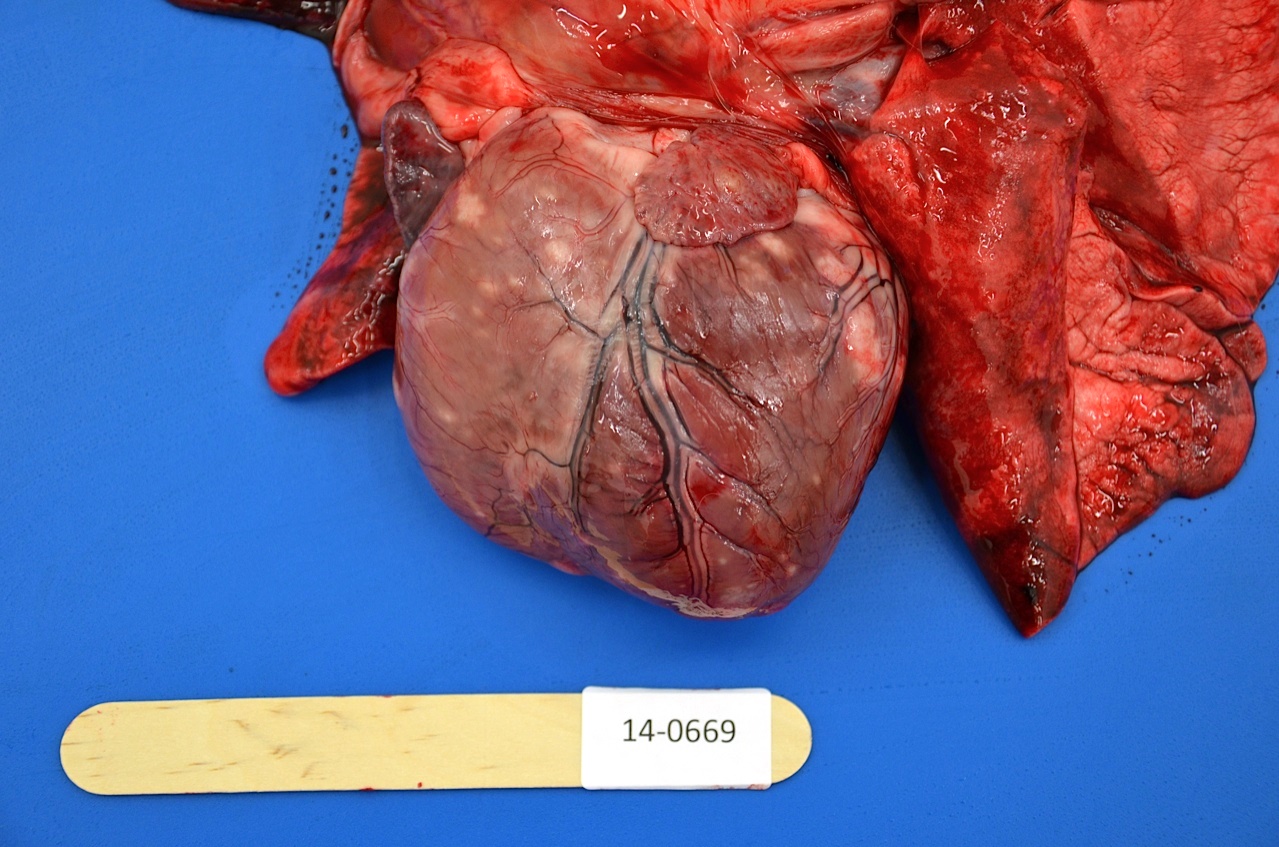

Gross Pathology:

A three-year-old female entire German shepherd dog in fair body condition was received for necropsy examination. The major finding at post mortem was pyogranulomatous discospondylitis and osteomyelitis at intravertebral space C5-C6 with bony destruction evident in the adjacent C5 and C6 vertebral bodies. Cytological examination of exudate from the C5-C6 disc space revealed neutrophilic and histiocytic inflammation admixed with numerous fungal hyphae. Disseminated granulomatous inflammatory foci were also identified in the myocardium and throughout the cortices of the left and right kidneys. There was multicentric subcutaneous, mediastinal, tracheobronchial and mesenteric lymphadenomegaly, and follicular lymphoid hyperplasia in the spleen. The uterus was gravid and four fetuses estimated at 5 weeks gestation age were present.

Laboratory Results:

Fungal organisms identified as Paecilomyces variotii were isolated from the vertebral disc lesion at C5-C6. Bacterial cultures from renal and vertebral lesions revealed no growth. Urinalysis (cystocentesis at necropsy) showed sub-optimal urine concentration (USG ? 1.015), a pH of 6, and was otherwise unremarkable. There were no significant findings on sediment examination.

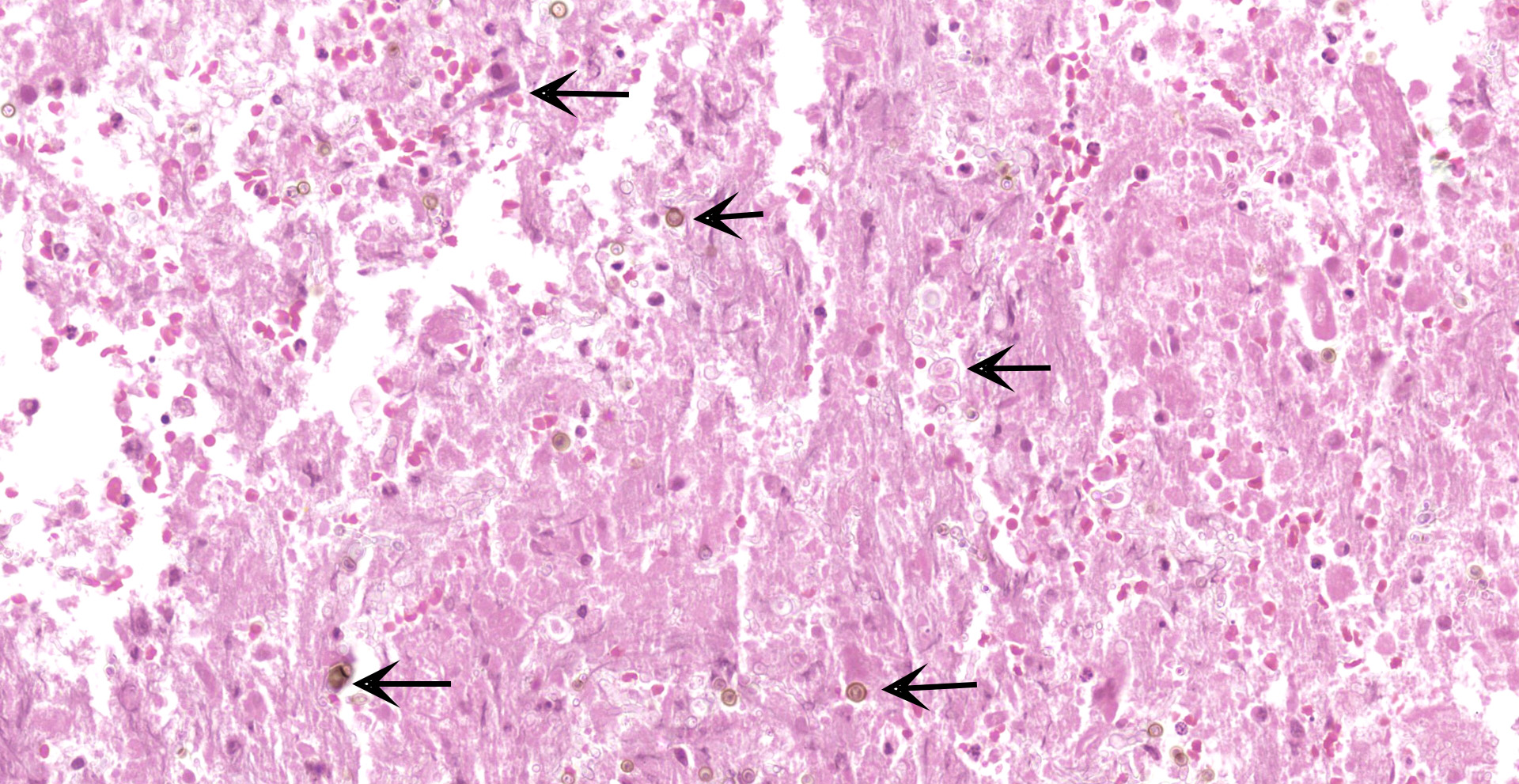

Histopathologic Description:

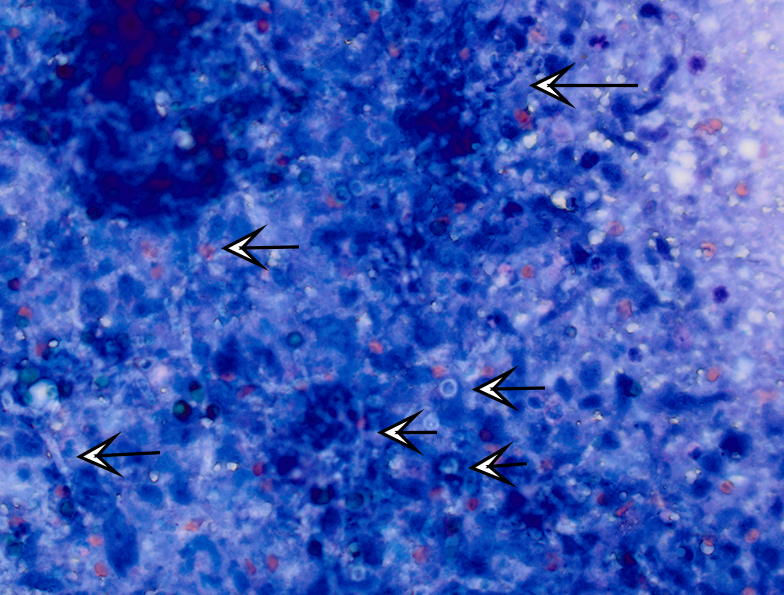

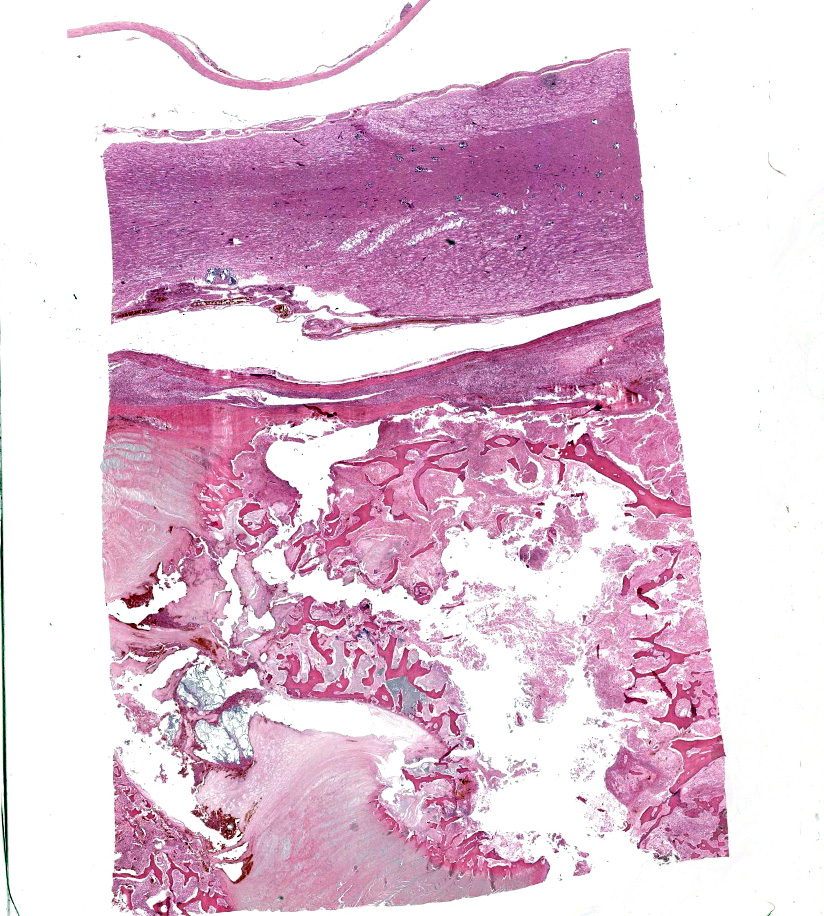

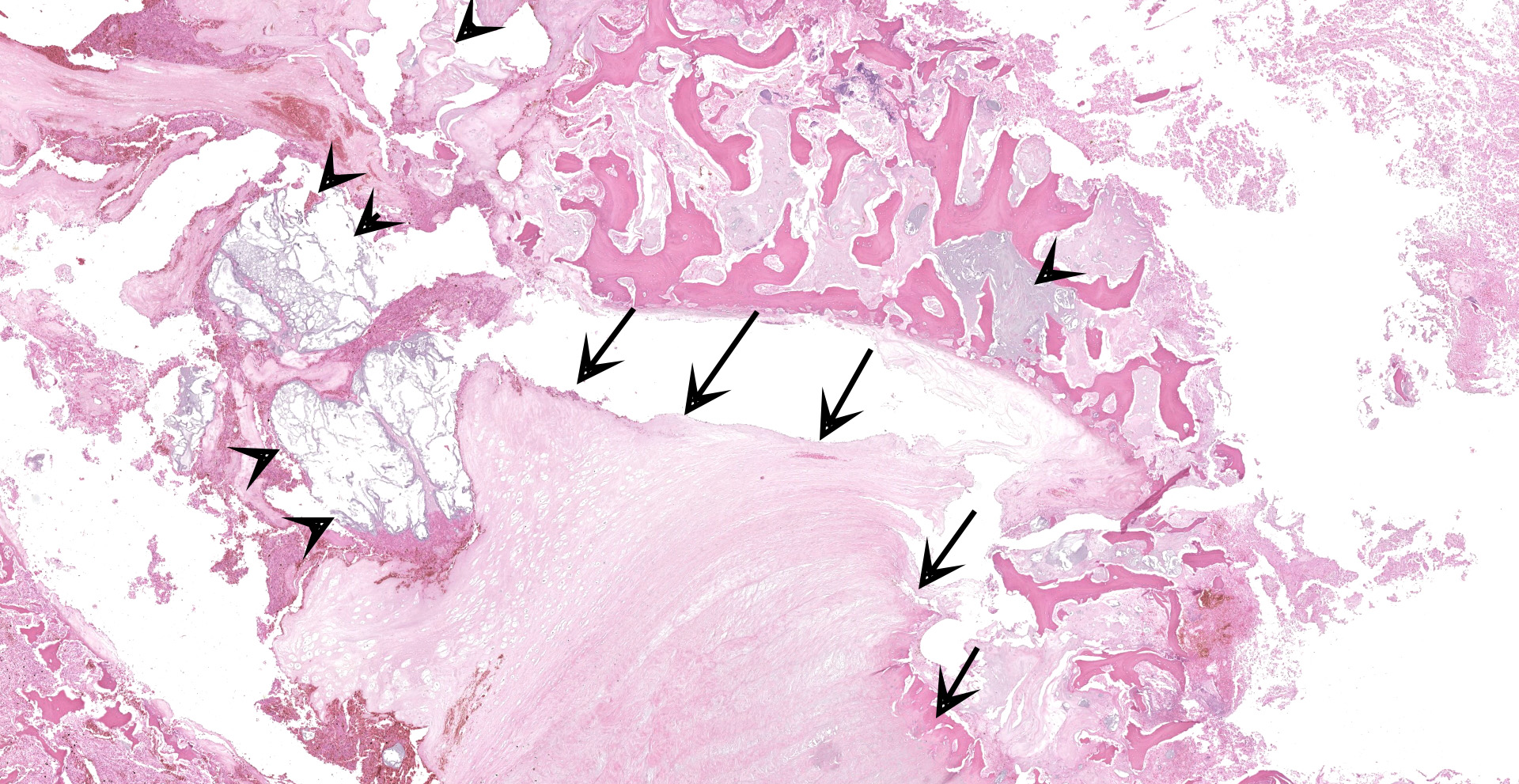

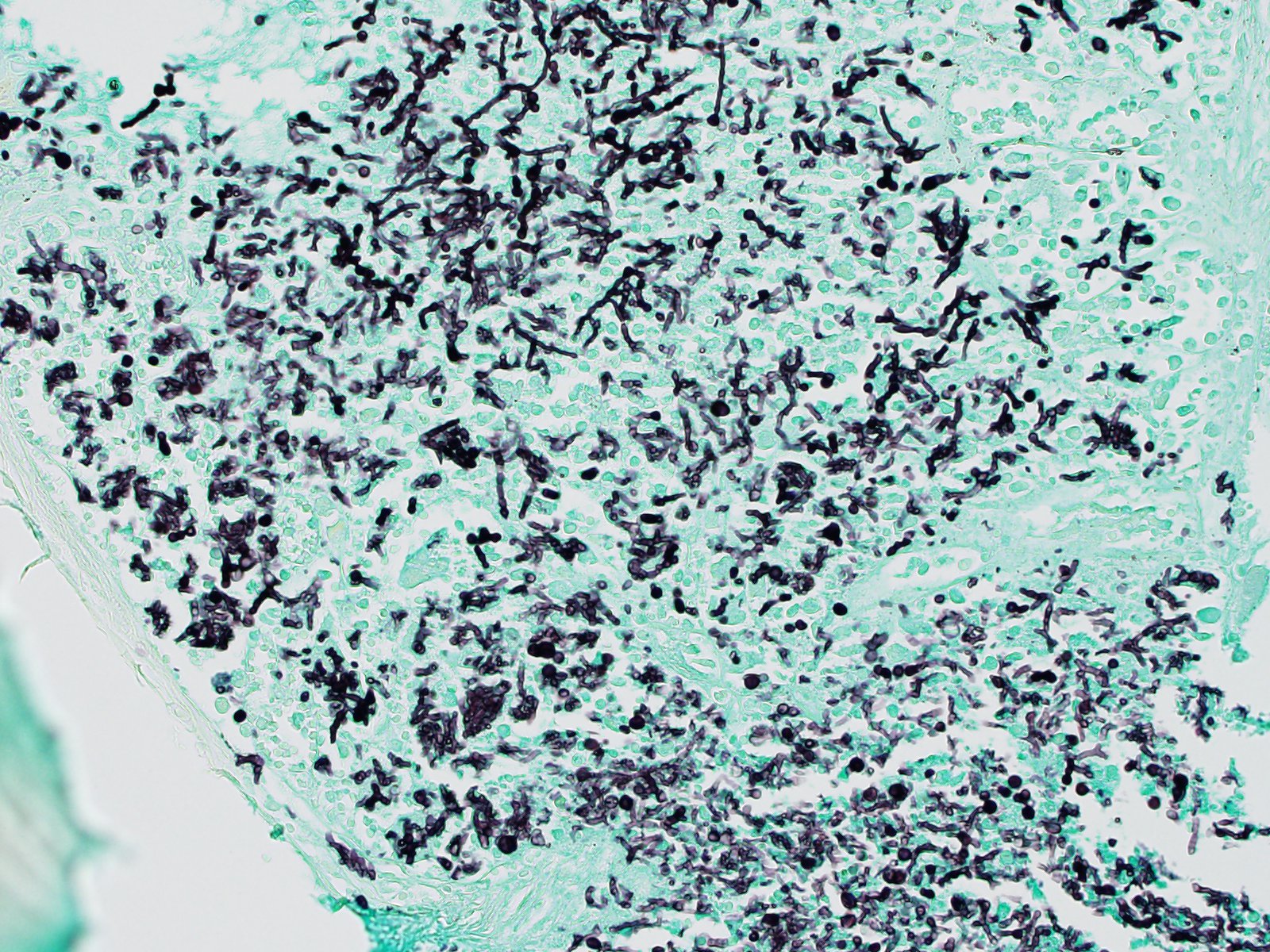

C5 and C6 vertebral bodies, intervertebral disc and spinal canal and cord (following decalcification): There is fragmentation and fibrillation of the intervertebral disc body, with expansion and effacement of the disc, marrow of adjacent vertebral bodies, and above subdural space by dense infiltrates of degenerate and non-degenerate neutrophils, macrophages, lesser lymphocytes and plasma cells, hemorrhage and fibrin. There is focally extensive loss of cellular detail and nuclear loss in trabecular bone (necrosis) and increased osteoclastic activity along the scalloped margins of thinned vertebral trabeculae in regions adjacent to inflammation (osteoclastic resorption). Refractile pale yellow-brown walled fungal hyphae are present admixed with dense inflammatory infiltrates, and PAS stain highlights extracellular and phagocytosed fragments of fungal hyphae. Hyphae are septate with non-parallel walls and occasionally show dichotomous branching and terminal budding structures (chlamydospores).

Microscopic examination of additional tissues: Granulomatous or pyogranulomatous inflammation with intralesional fungal organisms were present in the myocardium, kidneys, spleen, mediastinal, mesenteric and subcutaneous lymph nodes, myocardium, adrenal glands, pancreas and liver.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

C5 and C6 vertebrae and intervertebral disc space: Pyogranulomatous and fibrinous discospondylitis, osteomyelitis, osteolysis and meningitis with intralesional fungal hyphae

Contributor's Comment:

Discospondylitis and osteomyelitis with concurrent disseminated systemic fungal infection was the cause of illness in this pregnant female dog, and organisms isolated from the C5-C6 intervertebral disc were identified as Paecilomyces variotii. Disseminated fungal disease is not an uncommon finding in German Shepherd Dogs (GSDs), although bacterial causes of discospondylitis are far more common across all breeds, particularly Staphylococcus aureus and S. pseudintermedius.2 Paecilomycosis is also an uncommon cause of canine systemic mycosis, with the main fungal agent being Aspergillus terreus, and less commonly A. deflectus, A. flavus, A. flavipes, and other genera such as Acremonium, Penicillium and Chrysosporium.8 Paecilomyces is one of several causes of hyalohyphomycosis, a term referring to local or disseminated granulomatous disease caused by opportunistic, non-pigmented, hyphal fungal organisms.9 Although rarely pathogenic, Paecilomyces spp. are an important albeit infrequent cause of morbidity in dogs, reptiles and humans, and have also been noted in cats, horses and rodents.1,6,7,14,15 The species P. variotii has been isolated from canine, equine and rodent patients.7,12 Paecilomyces spp. are common environmental filamentous saprophytic fungi found airborne, and in soil, vegetative material, dust and food products worldwide, as well as being part of the normal microflora of canine hair.1,2,6,7,9,12,14,15 Consequently interpretation of positive cultures is somewhat subjective given the possibility of contaminants, which may contribute to Paecilomyces being over looked as an aetiological agent.2,6,7 In addition culture is typically poorly sensitive, possibly because of poor tissue concentrations of fungus in accessible areas.7

Paecilomyces spp. are anamorphic ascomycete molds, and are close relatives of Penicillium spp.7 Their mycelia have yellow-brown, broad, branching, septate hyphae, leading into smooth walled conidiophores bearing wide-based, long necked phialides which often bend away from the main axis, and themselves bear ellipsoidal smooth-walled conidia.6,11 Chlamydospores, the result of asexual or less commonly sexual reproduction, may also be present either singularly or in short chains, and are brown, roughened, globose and thick-walled.11 Their morphology may be confused with Aspergillus spp. and Candida spp., hence fungal culture is always recommended.14 The Paecilomyces genus is comprised of 15 different species including P. variotii (several spelling variations exist in literature), viridis, tenuipes, sinensis, pericinus, marquandii, lilacinus, javanicus, fumosoroseus, flavinosus, carneus, canescens and aerugineus. The majority of these species have been isolated from human and veterinary patients, most frequently P. variotii and P. lilacinus.9 Speciation of Paecilomyces is important in clinical cases because it carries therapeutic implications, with P. variotii susceptible to most common antifungals, and P. lilacinus highly resistant.2

Clinical paecilomycosis ranges from mild to severe localized infections such as keratitis, endocarditis, sinusitis, nephritis and pneumonia, to disseminated infections with fungemia.7 Granulomatous or pyogranulomatous nephritis, myocarditis, splenitis, lymphadenitis, pancreatitis, adrenalitis and hepatitis noted in this case is consistent with haematogenous seeding of a systemic fungal infection. The most common presentation of paecilomycosis in dogs is discospondylitis with or without dissemination.6,7

Foley et al. (2002) conducted a review of paecilomycosis in dogs at the University of California Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital between 1980 and 2000 (10 dogs) as well as case reports in veterinary medical literature (9 dogs): German Shepherd Dogs (GSDs) (8/19) and females (16/19) were over represented. The exact mechanisms for these gender and breed predispositions are unknown, although in general both female dogs and GSDs have increased rates of fungal diseases.2,6,7,14,15 Proposed mechanisms in GSDs include depressed local cellular responses, and IgA dysregulation resulting in decreased mucosal immunity.15 The role of immunomodulation due to pregnancy in this dog is uncertain; in humans, pregnancy is a reported risk factor for development of disseminated coccidiomycosis.3,10,16

Most canine patients in the 2002 review study had discospondylitis with (7/19) or without (6/19) disseminated fungal infection, with the remainder having disseminated or localized mycosis in other locations, including the liver, spleen, visceral or peripheral lymph nodes, and the kidneys.6,7,9 The primary lesion of systemic paecilomycosis is usually not determined although authors in previous case reports have suspected cutaneous or mucosal wounds.2,6,8 An unusual presentation was documented in a 2008 case report, in which a 4-year-old spayed female mixed-breed dog with disseminated Paecilomyces variotii developed generalized calcinosis cutis, a phenomenon only previously reported in three dogs with blastomycosis.9

Localized paecilomycosis in dogs has been reported in the skin, nasal cavity, inner ear, prostate and bladder.7,9 A recent case report described an unusual presentation of localized paecilomycosis; a six-year-old entire female GSD with bilateral obstructive pyelonephritis caused by Paecilomyces bezoars, without concurrent disseminated disease.15 In this case fungal infection was first identified using a pyelocentesis sample for urine sediment examination, and confirmed with urine culture. In a similar case of paecilomycosis in a 3-year-old castrated male GSD, also involving both kidneys, a cystocentesis sample was similarly use to reach a definitive diagnosis.6 Interestingly in some cases, such as the case presented here, urine sediment and urine culture results are negative, despite the presence of fungal organisms in both kidneys.2

Patients with paecilomycosis sometimes have concurrent, possibly predisposing conditions, with examples in literature including immunosuppressive corticosteroid therapy, neoplasia, skin trauma, diarrhoea and otitis.7,15 By contrast in man paecilomycosis is usually accompanied by an underlying immunosuppressive disorder, facilitating spread from localized areas of infections, which in humans are usually contaminated wounds or prosthesis implants.1,9,14,15 Paecilomycosis associated with pneumonia, discospondylitis or disseminated infection carries a grave prognosis, with reported mortality rates ranging from 57-100%.5,15

Contributing Institution:

The University of Adelaide, Roseworthy, South Australia. https://www.adelaide.edu.au/vetsci/

JPC Diagnosis:

Cervical vertebral body and adjacent inter-vertebral disk: Discospondylitis, pyogranu-lomatous, diffuse, severe with numerous intra- and extracellular pigmented fungal conidia and hyphae.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an outstanding and thorough review of the host range, risk factors, pathogenesis, clinical signs, gross and histologic features, and comparative pathology associated with paecilomycosis.

Interestingly, the first published case of a disseminated canine mold infection (DCMI) was attributed to Paecilomyces spp. in a Weimaraner in 1971, despite the now known overrepresentation of German shepherd dogs (GSDs) and Aspergillus spp. The first DCMI case reported in a GSD was in 1978 and attributed to Aspergillus terreus.5

Similar to as reported in the contributor's comment, a 2018 review5 of 112 cases of DCMI found GSDs to be predisposed, with the breed representing 67.8% of the cases. Furthermore, 89.7% of infections in this breed were attributed to Aspergillus section Terrei, which includes A. terreus sensu stricto, A. carneus, A. niveus, A. alabamensis, and A. terreus var. aureus. These species are morphologically identical and require molecular techniques for speciation. Across all breeds, females are at increased risk for DCMI, while sterilization is not associated with significantly increased risk in either sex. A wide age range (1-13 years) was affected, with the average age of infection reported to be 4.3 years.5

DCMI is thought to undergo dissemination primarily via the hematogeous route, which is facilitated by specialized structures produced by each organism. Paecilomyces spp. produce conidia in vivo, known as 'adventitious forms'. Similarly, A. terreous, as well as other fungi in sections Flavipedes and Jani produce structures known as 'accessory spores' or 'aleuriospores', which differ from phialidic conidia by growing directly on hyphae in both culture and infected tissue. It is believed these structures enter systemic circulation and subsequently arrest in capillary loops and other regions with reduced speed of blood flow, likely explaining why the kidneys and vertebrae are frequently affected in cases of DCMI.5

In addition to domestic and laboratory species, paecilomycosis has been identified in multiple wildlife species. Reptiles appear to be particularly susceptible, with confirmed infections reported in an American alligator (Alligator mississipiensis), an estuarine crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), a spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus), 2 Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus), 4 carpet chameleons (Chameleo lateralis), 2 Aldabra giant tortoises (Geochelone gigantea), and several green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) hatchlings. Proposed risk factors associated with infections in these species include stress of shipping with chameleons, skin trauma with crocodilians, and excessively cold water with green sea turtle infections. Reptiles are most commonly infected by P. lilacinus.7

Interestingly, Paecilomyces spp. have been identified as a source of numerous bioactive products, with 223 metabolites identified in one recent report4, including highly toxic linear peptides known as leucinostatins, paeciloquinones (tyrosine kinase inhibitors), macrocyclics, and trichothecans. Therefore, there is tremendous potential associated with genus Paecilomyces in regard to the development of applications such as antimicrobials, antivirals, nematicidals, and free radical scavenging.4 In addition to producing potentially useful compounds, some species having been found to have potentially useful applications in regard to agriculture, including both P. farinosus and P. fumosoroseus. Both of these species are known to infect insect and arachnid hosts, with the latter having been evaluated as a biological agent to suppress agricultural pests such as Russian wheat aphid and silver-leaf whiteflies.7

Although there is great potential in regard to the ongoing discovery of positive applications of Paecilomyces, the saprophytic fungus has also been implicated with food spoilage and other detrimental effects.4 As an example, P. varioti thrives in substrates such as aviation fuel, while also producing corrosive acid metabolites and clogging filters with its mycelia. In addition, other species are known to contaminate laboratories, allegedly sterile solutions, and chlorinated drinking water.7

Participants did not observe an inflammatory process within the meninges within the section presented and therefore did not favor inclusion of 'meningitis' in the morphologic diagnosis. However, it is possible this lesion is represented in other sections due to slide variability.

Additional discussion centered on the use of the terms 'yeast', 'spore', and 'conidia' in regard to fungal propagules. Yeasts are a single celled form of fungi that produce by budding. Dimorphic fungi grow as yeast (or spherules) at 37⁰C and as molds (multicellular hyphae) at 25⁰C. Spores can be produced either asexually or sexually. Asexual spores are always formed in a sporangium and undergo cytoplasmic cleavage following mitoses. Sexual spores undergo meiosis and are associated with several unique structures such as basidiospores, zygospores, and ascospores. Conidia are similar to asexual spores in that they are always asexual in origin but never develop in a manner that involves cytoplasmic cleavage.13

Finally, several fungi (as in this case) have melanin in the cell wall of conidia, hyphae, or both. In such cases, the fungi are considered to be dermatiaceous.13

References:

1. Athar MA, Sekhon AS, McGrath JV, Malone RM: Hyalohyphomycosis caused by Paecilomyces variotii in an obstetrical patient. European Journal of Epidemiology 1996:12(1):33-35.

2. Booth MJ, van der Lugt JJ, van Heerden A, Picard JA: Temporary remission of disseminated paecilomycosis in a German shepherd dog treated with ketoconazole. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association-Tydskrif Van Die Suid-Afrikaanse Veterinere Vereniging 2001:72(2):99-104.

3. Busowski JD, Safdar A: Treatment for coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy? Postgrad Med 2001:109(3):76-77.

4. Dai ZB, Wang X, Li GH. Secondary Metabolites and Their Bioactivities Produced by Paecilomyces. Molecules. 2020;25(21):5077.

5. Elad D. Disseminated canine mold infections. Vet J. 2019;243:82-90.

6. Feigin K, Penninck D, Labato MA, Acierno M: A challenging case: A German shepherd with a decreasing appetite and azotemia. Veterinary Medicine 2006:101(2):94-+.

7. Foley JE, Norris CR, Jang SS: Paecilomycosis in dogs and horses and a review of the literature. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2002:16(3):238-243.

8. Garcia ME, Caballero J, Toni P, Garcia I, de Merlo EM, Rollan E, et al.: Disseminated mycoses in a dog by Paecilomyces sp. Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series a-Physiology Pathology Clinical Medicine 2000:47(4):243-249.

9. Holahan ML, Loft KE, Swenson CL, Martinez-Ruzafa I: Generalized calcinosis cutis associated with disseminated paecilomycosis in a dog. Veterinary Dermatology 2008:19(6):368-372.

10. Hooper JE, Lu Q, Pepkowitz SH: Disseminated coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2007:131(4):652-655.

11. Kozakiewicz Z, Uk CABI: Paecilomyces variotii. Descriptions of Fungi and Bacteria. IMI Descriptions of Fungi and Bacteria 2000(143):1427-Sheet 1427.

12. Kunstyr I, Jelinek F, Bitzenhofer U, Pittermann W: Fungus Paecilomyces: A new agent in laboratory animals. Laboratory Animals 1997:31(1):45-51.

13. McGinnis MR, Tyring SK. Introduction to Mycology. In: Baron S, ed. Medical Microbiology. 4th ed. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996.

14. Quance-Fitch FJ, Schachter S, Christopher MM: Pleural effusion in a dog with discospondylitis. Veterinary Clinical Pathology 2002:31(2):69-71.

15. Tappin SW, Ferrandis I, Jakovljevic S, Villiers E, White RAS: Successful treatment of bilateral paecilomyces pyelonephritis in a German shepherd dog. Journal of Small Animal Practice 2012:53(11):657-660.

16. Walker MP, Brody CZ, Resnik R: Reactivation of coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1992:79(5 ( Pt 2)):815-817.