Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 22

15 April, 2020

CASE I: NO-16-1279 (JPC 4099471).

Signalment: Adult male white-headed capuchin (Cebus capucinus).

History: Several New World and Old World monkeys (white-headed capuchin (Cebus capucinus), Booted macaque (Macaca ochreata), and Sooty Mangabey (Cercocebus atys)) in this primate facility had a sudden onset of severe depression, fatigue, lethargy, and sleepiness, then died within a few hours after first clinical signs.

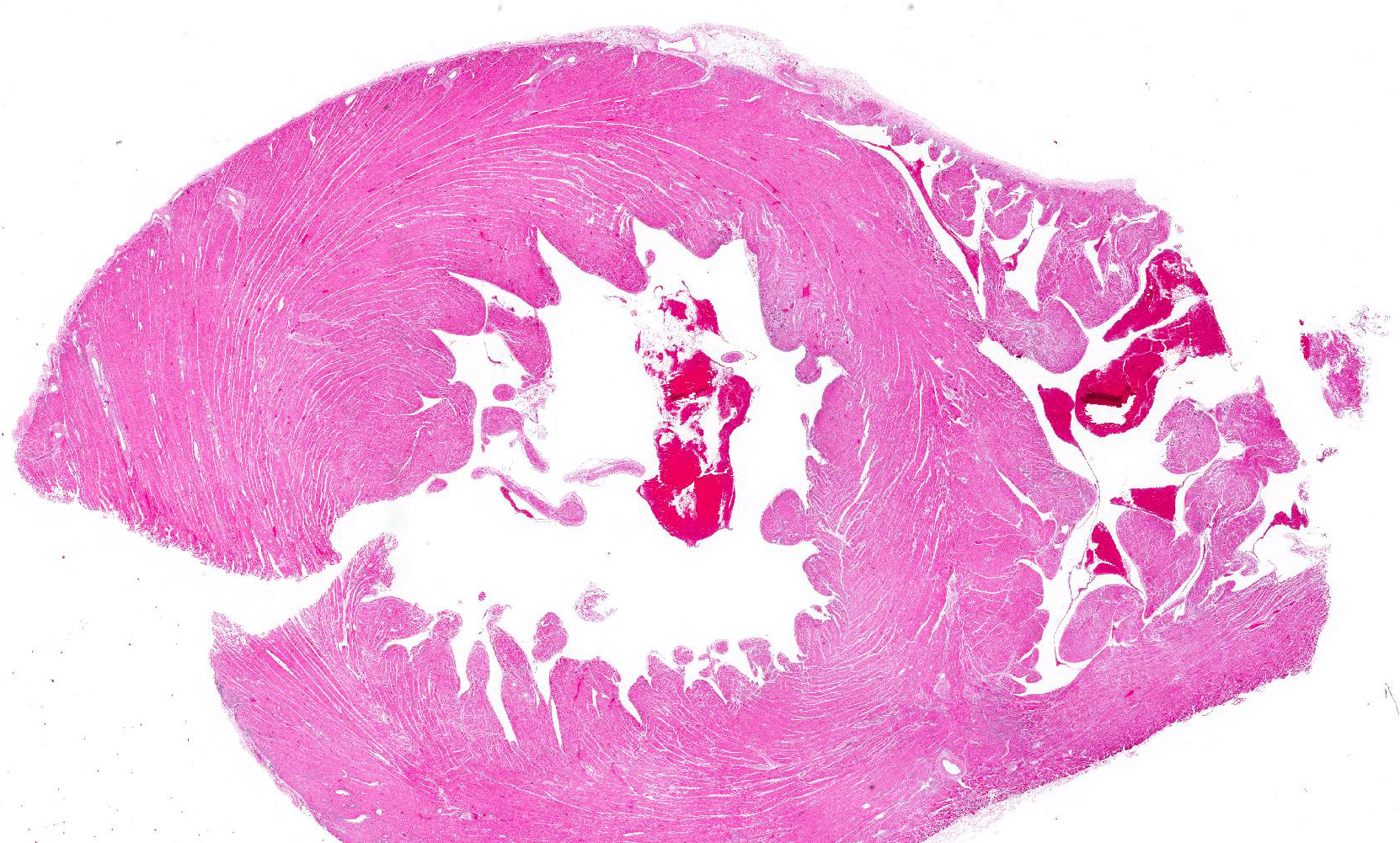

Gross Pathology: A 3.45 Kg adult male white-headed capuchin (Cebus capucinus) was in fair nutritional condition (body condition score of 4/9). Scleral and oral mucosa was diffusely pale pink. The heart was moderately enlarged and veins were dilated with clotted blood. There were multiple foci of slightly pale discoloration scattered throughout the left ventricular wall and near the heart apex. The discolored pale tan areas extended approximately 5-7 mm into the underlying myocardium. The apical region of pallor was approximately 3 mm in diameter at the epicardial surface. Lung lobes were diffusely pink; however, the right middle lobe had multifocal distinctly dull red demarcated, depressed areas.

The liver was slightly enlarged; the tip of the right lateral liver lobe extended 5-10 mm caudal to the costal margin.

Throughout the cerebrum and meninges, vessels were dilated and prominent. All other organs were grossly unremarkable.

Laboratory results:

- Bacteriology: Rare colonies of Staphylococcus aureus were isolated from submitted pulmonary tissue, and no bacterial colonies were isolated from submitted hepatic tissue.

- Virology: Virus isolation demonstrated prominent cytopathic effects from submitted fresh frozen pooled specimens including heart and brain. Encephalomyocarditis virus was detected from cell culture supernatant by PCR and confirmed by genetic sequencing. PCR to detect Herpesvirus, West Nile virus, and Francisella tularensis were negative.

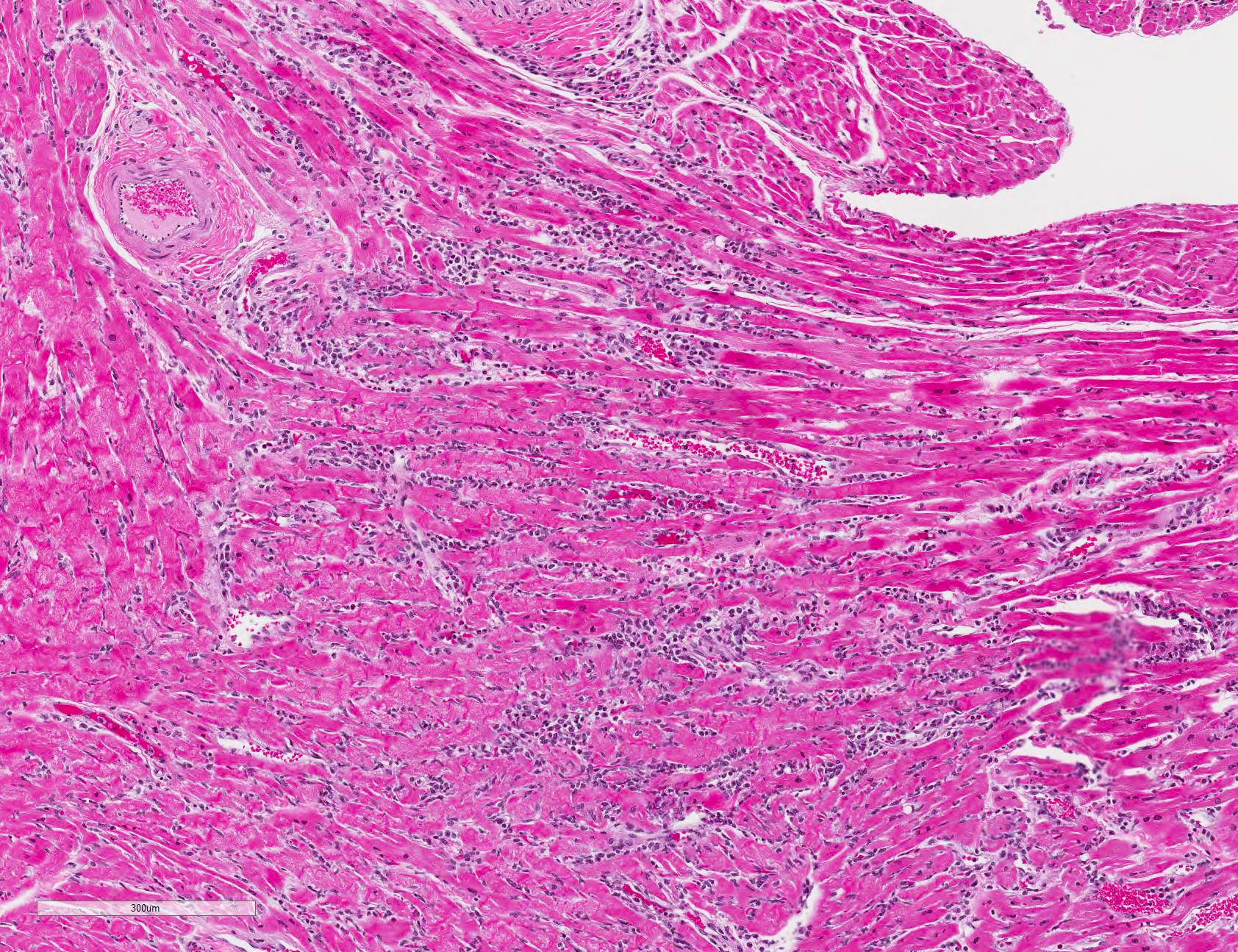

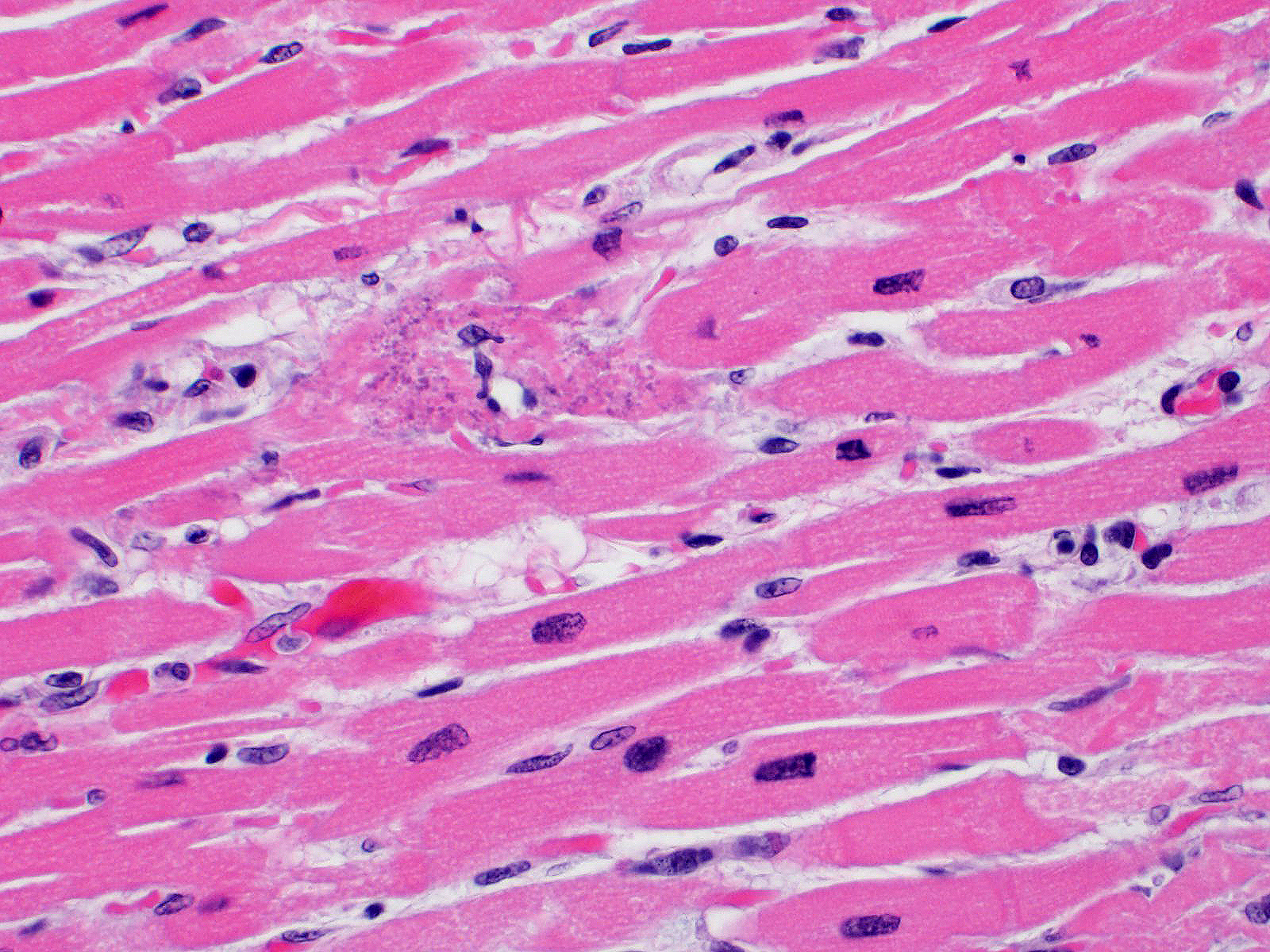

Microscopic Description: All representative sections of the heart contain similar inflammatory processes and will be described collectively; however, the degree of severity varies between sections. Multifocally, within examined sections of left and right cardiac ventricles, there are variably dense interstitial infiltrates of mixed inflammatory cells dissecting around the myocardial fibers and surrounding occasional vessels in some areas. These leukocytes include lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes mixed with fewer neutrophils. The affected cardiomyocytes are variably degenerating or necrotic characterized by hypereosinophilia, loss of cellular detail, formation of contraction bands, and nuclear pyknosis and karyorrhexis. In some areas, there is intracytoplasmic and extracellular basophilic granular mineralization.

Contributor?s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Heart: Myocarditis, necrotizing, moderate to severe, multifocal to coalescing

Contributor?s Comment: Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) is a small non-enveloped single-stranded RNA virus, classified as a member of family Piconaviridae, genus Cardiovirus. The virus is known to cause myocarditis and encephalitis in a variety of domestic mammals including pigs and several zoo and wildlife species including non-human primates.1,3,5,6,12 EMCV infection is also sporadically reported in humans, although the vast majority of cases are mild and asymptomatic.10

Rodents are considered to be reservoir hosts for EMCV in some studies,1,5 though studies have associated EMCV inoculation with severe to fatal myocarditis and necrotizing pancreatitis in Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) as well as acute orchitis in Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus).7,8

Infected non-human primates have a rapid disease course including severe depression and lethargy progressing to acute heart failure and death within 24 hours of clinical presentation. In some cases, the affected animal may suffer from progressive respiratory distress prior to death.2, 5 As in this case, gross findings are typically limited to the heart as evidenced by pale white discoloration or variable petechial and ecchymotic hemorrhage.1,2,5 Hydropericardium, hydrothorax, pulmonary congestion, and ascites may be observed in some cases. 2,3 The principal histologic findings of EMCV-infected non-human primates include multifocal regions of myocardial degeneration and necrosis with associated variable degrees of lymphocytic to mixed interstitial inflammatory infiltrates.

Neural lesions are uncommon in non-human primates, which suggests a cardiotropic nature of the virus in these hosts;4 however, some studies showed neurotropism of this virus in naturally and experimentally infected animals.1,6 Other infectious diseases that can be associated with myocarditis in non-human primates include West Nile virus, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Borrelia burgdorferi.

Contributing Institution:

Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health and the Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, College of Veterinary Medicine, Michigan State University. 4125 Beaumont Rd. Lansing, MI 48910 www.animalhealth.msu.edu; www.pathobiology.msu.edu

JPC Diagnosis: Heart: Myocarditis, necrotizing and lymphocytic, random, multifocal, moderate, with lymphocytic epi- and endocarditis.

JPC Comment: EMCV was first identified in a captive gibbon in 1945 that died suddenly from pulmonary edema and myocarditis. Mice inoculated with edema fluid from the affected monkey developed myocarditis and hindlimb paralysis. A similar virus was isolated 4 years later in the Mengo district of Entebbe, Uganda from a paralyzed rhesus macaque which was shown to be antigenically indistinct via sero-neutralization, but both viruses were considered distinct from the Theiler?s murine encephalomyelitis virus (another cardiovirus).2 The first outbreak in swine was noted in Panama in 1958.2

Although mice are considered to be the natural reservoir,

rats are often implicated in transmission to other species, including non-human

primates and swine. Transmission is most likely the result of fecal

contamination of feeds, although horizontal transmission has been identified in

swine and suspected in non-human primates.11

This virus has been shown to infect a wide range of non-human primates,

including rhesus macaques, mandrills, chimpanzees, marmosets, owl monkeys and

squirrel monkeys. 11 There have been a number of significant

outbreaks in captive baboons, suggesting that this species may be uniquely

susceptible.11 Many infected primates are found dead with minimal

premonitory signs, or suffer from rapidly progressing biventricular heart

failure with prominent edema and froth or fluid from the nose and mouth. As

mentioned by the contributor, the clinical picture in non-human primates is

primarily that of cardiac infection, however, neurotropic strains may also

cause lymphocytic infiltrates in the cerebrum.11

Encephalomyocarditis virus will also cause cardiovascular disease in a number of other species including pygmy hippopotamuses and exotic hoofstock, lemurs, tapirs, rhinoceroses, and elephants9 (perhaps explaining the elephant?s mythic fear of the mouse.) Transmission within zoo collections is considered to be the result of fecal and infected carcass contamination of feed. Myocarditis and heart failure is always present; neurologic lesions are uncommon.9

While considered a zoonosis, disease in humans is mild and somewhat controversial. Human cell lines are readily infected. EMCV has been incriminated in a number of cases of febrile human illness with clinical signs of headache, nausea and malaise, when EMCV virus was detected using molecular techniques in the absence of other viruses. Seropositivity to EMCV has ranged from 3-15% in the general population with higher rates in humans with occupational exposure and hunters. 2

References:

1. Canelli E, Luppi A, Lavazza A, et al. Encephalomyocarditis virus infection in an Italian zoo. Virol J. 2010;7(64). Published online 2010 Mar 18.

2. Carocci M, Bakkali-Kassimi L. The encephalomyocarditis virus. Virulence. 2012;3(4):351-367.

3. Citino SB, Homer BL, Gaskin JM, et al. Fatal encephalomyocarditis virus infection in a Sumatran orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus abelii). J Zoo Animal Med. 1988;19(4):214-218.

4. Craighead JE. Pathogenicity of the M and E variants of the encephalomyocarditis (EMC) virus. Am J Pathol. 1966;48(2):333-345.

5. Jones P, Cordonnier N, Mahamba C, et al. Encephalomyocarditis virus mortality in semi-wild bonobos (Pan panicus). J Med Primatol. 2011;40(3):157-163.

6. LaRue R, Myers S, Brewer L, et al. A wild-type porcine encephalomyocarditis virus containing a short poly(C) tract is pathologic to mice, pigs, and cynomolgus macaques. J Virol. 2003;77(17):9136-9146.

7. Matsuzaki H, Doi K, Mitsuoka T, et al. Experimental encephalomyocarditis virus infection in Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus). Vet Pathol. 1989;26:11-17.

8. Shigesato M, Takeda M, Hirasawa K, et al. Early development of encephalomyocarditis (EMC) virus-induced orchitis in Syrian hamsters. Vet Pathol. 1995;32:186-186.

9. Terio KA, McAloose D, St Leger J eds., In: Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals; London: Associated Press, 2019

10. Tesh R. The prevalence of encephalomyocarditis virus neutralizing antibodies among various human populations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27(1):144-148.

11. Wachtman L, Mansfield C. Viral diseases of non-human primates. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardiff S, Morris T, eds. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. London, Academic Press 2012, pp 73-74.

12. Wells SK, Gutter AE, Soike KF, et al. Encephalomyocarditis virus: epizootic in a zoological collection. J Zoo Wildl Med. 1989;20(3):291-296.