CASE 1: W2019 234 (4134350-00)

Signalment:

10 weeks old, female entire, mini lop, domesticated European rabbit, (Oryctolagus cuniculus)

History:

Two nine-week-old rabbits were purchased from a breeder. The next day the other rabbit in the group presented with progressive lethargy, inappetence, bradycardia, hypothermia, seizures, and recumbency and died shortly after. Four days later this rabbit was found dead with no clinical signs noticed and was submitted for postmortem examination.

Gross Pathology:

The liver was diffusely pale brown with an enhanced lobular pattern and friable texture. The spleen was enlarged 2-fold and the edge was rounded. On both kidneys there were multifocal, poorly demarcated, up to 1 mm diameter, pin-prick, red, sub-capsular foci (petechial hemorrhages).

Laboratory results:

Fresh frozen liver was submitted for rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) PCR. PCR for RHDV-2 was positive and RHDV-1 was negative.

Microscopic description:

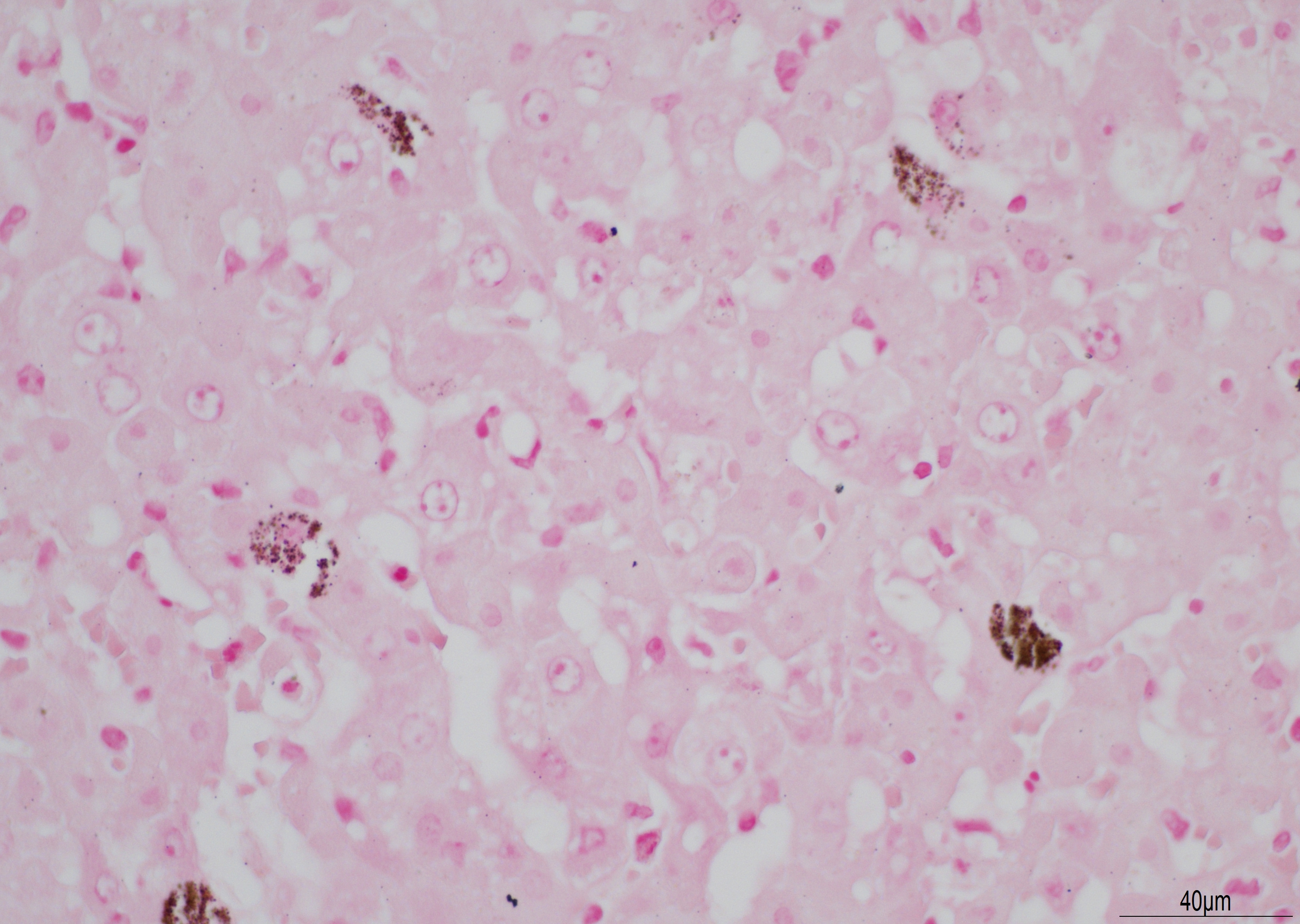

There is diffuse necrosis of periportal to midzonal hepatocytes, characterized predominantly by hypereosinophilic hepatocytes with faded nuclei (karyolysis) and retained cord architecture (coagulative necrosis). There are hepatocytes, which are multifocally dissociated from hepatic cords, that exhibit fragmented cytoplasm and karyorrhexis or pyknosis and are sometimes admixed with erythrocytes (lytic necrosis). Necrotic periportal hepatocytes infrequently exhibit numerous, variably sized, dark basophilic, cytoplasmic granules that stain positively with Von Kossa stain (calcification). There are small numbers of either individual or clustered heterophils scattered within necrotic areas. Portal areas contain moderate numbers of heterophils and small numbers of lymphocytes. In centrilobular regions there are small numbers of heterophils within sinusoids. In one section there is a focal grouping of portal areas mildly expanded by collagen bundles (fibrosis) with mild bile duct hyperplasia (this feature is not present in all sections submitted).

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

- Hepatocellular necrosis, periportal and midzonal, acute, diffuse, marked; liver, with

- Hepatitis, portal, heterophilic, acute, diffuse, moderate.

- Portal fibrosis, chronic, focal, mild; liver with

- Bile duct hyperplasia, chronic, focal, mild.

Contributor's comment:

The gross findings described in this case correlate with gross findings for RHDV-2 reported in the literature including a pale, friable liver with enhanced lobular pattern, splenomegaly, and renal petechiae.8 Gross findings may vary in severity and can include splenomegaly, petechial or ecchymotic hemorrhages in various organs, hemorrhage within body cavities and/or pulmonary hemorrhage and oedema.1 The most significant microscopic finding reported for RHDV-2 is periportal hepatocellular necrosis with varying degrees of severity, from scattered, individual necrosis of periportal hepatocytes to more diffuse, zonal necrosis, as in this case. Other reported findings include heterophilic infiltration of portal areas and hepatic parenchyma.8 Calcification of individual hepatocytes has not been reported in experimentally infected rabbits, although it has been reported in hares infected with European brown hare syndrome virus, a Caliciviridae closely related to RHDV. In these cases, the cytoplasmic granules corresponded ultrastructurally to mitochondrial calcification.6 The focal portal fibrosis and bile duct hyperplasia is considered most likely to be an unrelated finding in this case. The diagnosis can be confirmed by detection of RHDV-2 RNA in tissues or body fluids, ideally within fresh liver or spleen. RT-PCR is a rapid, highly sensitive method of detection that is readily available in Europe.5

RHDV is a member of the Lagovirus genus in the Caliciviridae family, along with European brown hare syndrome virus. Caliciviridae are positive sense, single stranded RNA viruses enclosed in an icosahedral capsid. A new, distinct variant of RHDV, named RHDV-2 or Lagovirus europaeus/GI.2/RHDV2/b, was first detected in France in 20107 and subsequently in other mainland European countries and Great Britain.10 By 2018 it had been detected in Africa, Oceana, western Asia, and North America affecting both domestic and wild rabbits.9 While some of the earliest RHDV-2 strains in France were reported to have a mortality rate of 20-30%, more recent strains in Europe and Australia have mortality rates of 70-100%.4 Unlike RHDV-1, kittens are highly susceptible to RHDV-2.8 Transmission can be direct through contact with infected rabbits shedding virus in secretions or via a fecal-oral route. Indirect transmission can occur via contaminated fomites such as food, bedding, clothing or equipment or via mammalian, avian or blood-feeding insect vectors.1 The RHDV virus binds host-cell histo-blood group antigens (HBGA) on the surface of upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract epithelial cells. After internalization and desencapsidation the positive sense RNA viral genome proceeds to translation and replication. The virus targets the liver rapidly following infection and replicates within hepatocyte cytoplasm. Structural protein VP10, which is translated from open reading frame 2 (ORF2), promotes apoptosis and so contributes to the cytopathic effects of the virus.1

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Medicine,

The Queen's Veterinary School Hospital, University of Cambridge.

Cambridge CB3 0ES, UK.

JPC diagnosis:

Liver: Necrosis, periportal and midzonal, diffuse, with rare hepatocellular mineralization.

JPC comment:

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) remains an important pathogen in rabbit populations, causing mass mortality events from either natural infection, or as a method of population control. Domesticated rabbits were introduced to Australia in the 19th century, and the first reported feral population of rabbits was in Tasmania in 1827. They reached areas of mainland Australia (New South Wales, Queensland) by 1886 and spread to their present-day range by 1910. As an introduced/invasive species to Australia, they are prolific procreators, compete with native wildlife for food resources, and prevent some plant regrowth by eating seeds and seedlings. Rabbits are implicated as a potential cause of extinction of several small grown-dwelling mammals, the local decimation of two plant species, and a threat to populations of small mammals, plants, and some seabirds.2

The Commonwealth Government (federal Australian Government) uses a multipronged approach to reduce the population of rabbits, including biologic pathogens, chemicals, and mechanical interventions. Chemical methods include poisoning with sodium fluoroacetate, chloropicrin, and carbon monoxide, with physical destruction of habitat and warrens also a component of control. While one biologic method of control is the Myxoma virus, they also regularly release one strain of RHDV-2. The rabbit populations have developed resistance, and research into releasing new strains is under way.2

A recent case of RHDV in a German zoo affected the population of captive mountain hares. Previous research has shown that experimental infection with GI.1 RHDV in European brown hares induces antibody production but does not result in clinical disease. Hare populations experience differing extent of disease, with many species reporting significant pathology and mortality associated with GI.2 RHDV-2 strains. Sequencing of the isolated virus confirmed a previously sequenced strain of GI.2, suggesting the importance of cross-species transmission of this virus in endemic areas.3

The basophilic stippling seen multifocally on viable hepatocytes in this slide stained positively for both Von Kossa (indicating mineral) and a Perl?s iron stain and was ultimately diagnosed as ferrugination. The cause of this is unclear and a similar change was seen in the 2019 WSC in a case of a dog with widespread necrosis due to CAV-1.

References:

1. Abrantes J van der Loo W, Le Pendu, Esteves PJ. Rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV): a review. Vet Res. 2012;43(1):12-31.

2. Australian Government, Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Feral European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). 2011. https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/7ba1c152-7eba-4dc0-a635-2a2c17bcd794/files/rabbit.pdf. Accessed on 19 Oct 2020.

3. Buehler M, Jesse ST, Kueck H, et al. Lagovirus europeus GI.2 (rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus 2) infection in captive mountain hares (Lepus timidus) in Germany. BMC Veterinary Research. 2020;16:166.

4. Capucci L, Cavadini P, Schiavitto M, Lombardi G, Lavazza A. Increased pathogenicity in rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus type 2 (RHDV2). Vet Rec. 2017;180(17):426-427.

5. Duarte DM, Carvalho CL, Barros SC, et al. A real time Taqman RT-PCR for the detection of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus 2 (RHDV2). J Virol Methods. 2015;219:90?95.

6. Gavier-Widén D. Morphologic and Immunohistochemical Characterization of the Hepatic Lesions Associated with European Brown Hare Syndrome. Vet Pathol. 1994;31(3):327?334.

7. Le Gall-Reculé G, Zwingelstein F, Boucher S, et al. Detection of a new variant of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus in France. Vet Rec. 2011;168(5):137?138.

8. Neimanis A, Larsson Pettersson U, Huang N, Gavier-Widén D, Strive T. Elucidation of the pathology and tissue distribution of Lagovirus europaeus GI.2/RHDV2 (rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus 2) in young and adult rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Vet Res. 2018;49(1):46-60.

9. Rouco C, Aguayo-Adán JA, Santoro S, Abrantes J, Delibes-Mateos M. Worldwide rapid spread of the novel rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (GI.2/RHDV2/b). Transbound Emerg Dis. 2019;doi:10.1111/tbed.13189.

10. ?Westcott DG & Choudhury B. Rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus 2-like variant in Great Britain. Vet Rec. 2015;176(3):74-76.