Conference 14, Case 2:

Signalment:

9-year-old male Arabian horse (Equus ferus caballus)

History:

A 9-year-old male Arabian horse from Lagoa Santa (State of Minas Gerais, Brazil), was admitted to the veterinary hospital of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) with history of acute ataxia, depression, incoordination and reluctance to move. The horse belonged to a riding school, where no other horses showed any neurological signs, and was dewormed with Ivermectin. Therapy with steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was instituted (unknow drugs and dosages) at the horse training site, and the animal was anesthetized with detomidine and ketamine for the transport to UFMG. At admission, the horse was still anesthetized. When no longer anesthetized, the horse made several unproductive attempts to stand. Neurological signs progressed over the next 24 hours to bilateral ventromedial strabismus and reduction of threat response.

Physical exam revealed hypothermia (36.1°C), dry mucous membranes, increased capillary refill time, skin ulcers secondary to decubitus in the tuber coxae, head and limbs, as well as a superficial wound in the atlanto-occipital region, probably due to previous fall.

At the veterinary hospital, intravenous (IV) fluid therapy with 7.2% hypertonic saline solution, followed by Ringer’s lactate solution dimethyl sulfoxide (IV), ceftiofur, and dexamethasone therapy was initiated. Skull radiograph showed no significant abnormalities. Due to poor prognosis and lack of response to therapy the horse was euthanized and subject to necropsy.

Gross Pathology:

The kidneys had multifocal nodules, ranging from 2 to 15 cm in diameter, elevated, white-yellowish in the center, red on the edges, and firm. In the right kidney the lesion replaced, approximately, fifty percent of the renal parenchyma, whereas in the left kidney there were multiple nodules ranging from 1 to 3 cm in diameter. Renal and internal iliac lymph nodes were moderately enlarged and firm, with undefined cortico-medullary distinction. Meninges and brain parenchyma were moderately hyperemic.

Laboratory Results:

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed no change in color (clear), protein (34.02 mg / dL) and glucose (61.5 mg / dL). A mild increase in nucleated cells were observed (20 cells / μL, reference value: 5 cells / μL). No erythrocytes, eosinophils or parasitic structures were observed.

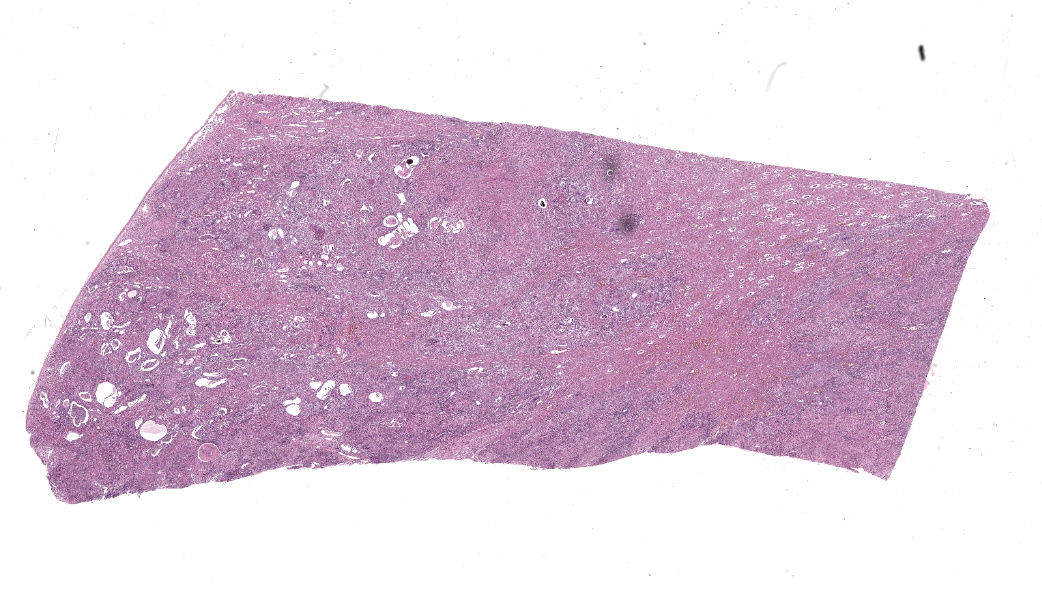

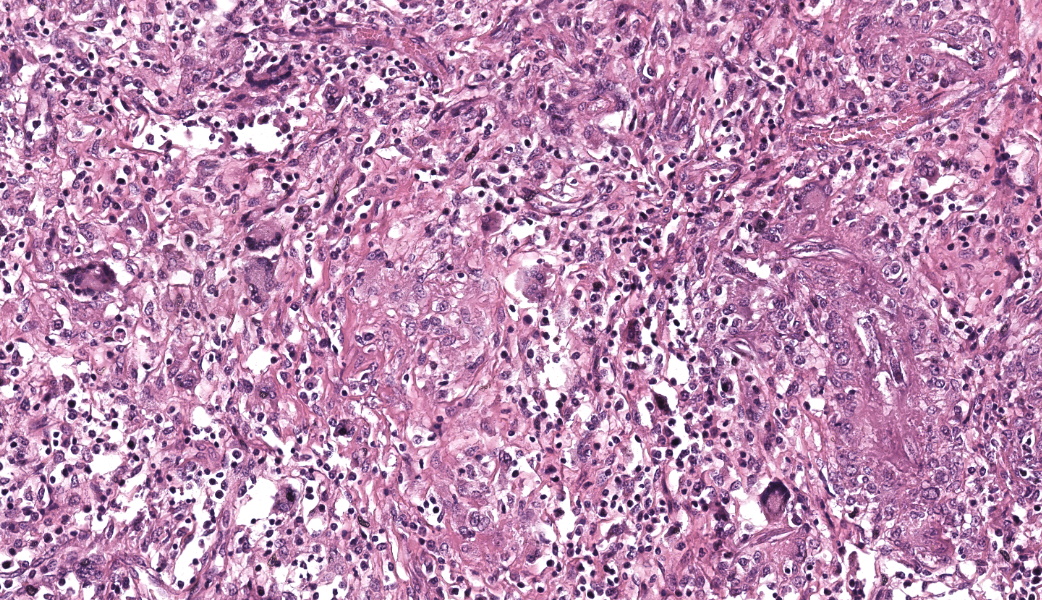

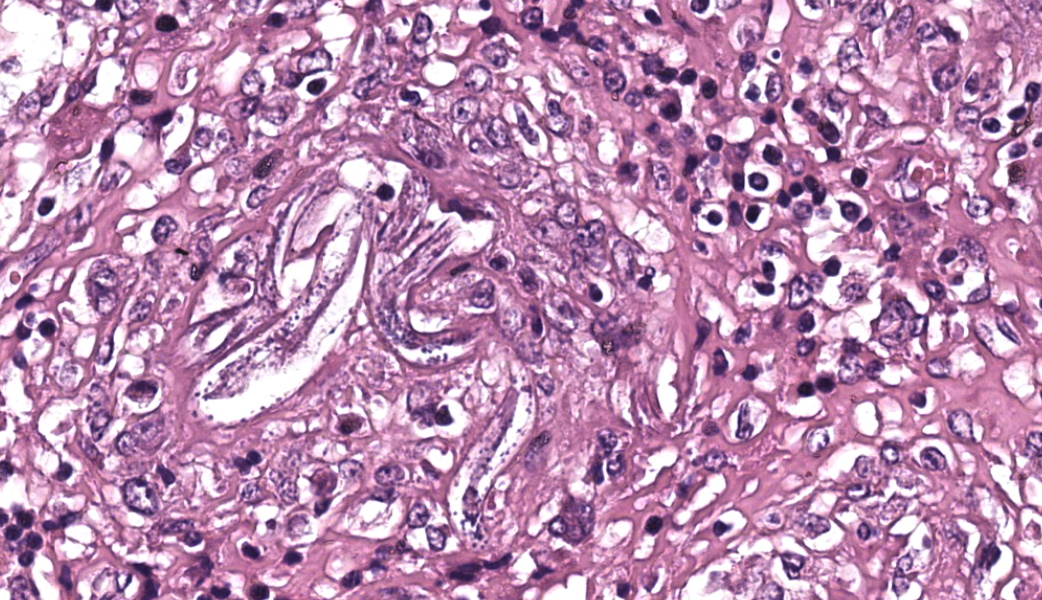

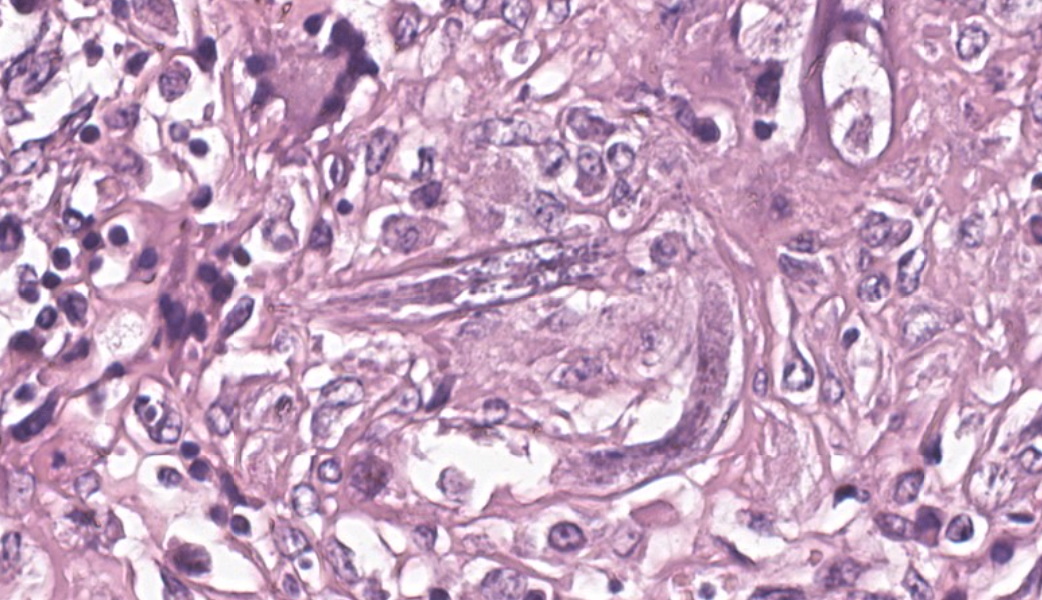

Microscopic Description:

Kidneys: Multifocal to coalescent areas of loss of normal parenchyma with replacement by severe lymphohistioplasmocytic inflammatory infiltrate, with epithelioid macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and large numbers of intralesional nematodes. Parasites were elongated, with aproximately 80 to 90 μm long (most of them fragmented), cylindrical, with sharp ends, covered by smooth cuticle, platimiarian musculature and an evident elongated and central rhabditiform esophagus, occupying the initial third of the body (morphology consistent with Halicephalobus gingivalis). Associated with these lesions there were also fibroplasia, necrosis, vasculitis and the remaining renal tubules were dilated and filled with macrophages, neutrophils, cellular debris, and numerous sections of H. gingivalis.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Kidneys: multifocal to coalescent, severe, chronic, granulomatous nephritis associated to intralesional nematodes compatible with Halicephalobus gingivalis and multifocal, severe, vasculitis, horse.

Contributor’s Comment:

H. gingivalis is a nematode, genus Halicephalobus, order Rhabditida, superfamily Rhabditoidea and family Rhabditidae that have a smooth and thin cuticle, with transverse striations, conical tail ending in fine point, elongated buccal cavity and a rhabditiform esophagus.2 It is a free-living nematode, usually found in the soil and organic matter, but its life cycle and pathogenesis are still unknown. Apparently, skin or mucosal lesions are the port of entry from where the parasite spreads by hematogenous or lymphatic route. Other

possible ways of dissemination in organs are through the optic or trigeminal nerves, and the lacrimal duct.3,7,9,10

gingivalis often infects horses. However, there are reported infections affecting zebra, calves, and humans.5,6,8 Most of the human and equine reported cases were from Europe, North America, and Northeast of Asia. Brazil have just three previously reported cases in horses, two of them with brain infection and one with granulomatous myocarditis.4,11,13 Clinical signs in infected animals reflect the distribution and intensity of the lesions. The lesions observed on the organs of this horse are compatible with other reports.6,11,13

Diagnosis of H. gingivalis infection based on direct detection of larvae by CSF analysis has been previously reported.1 However, there are no studies demonstrating a correlation between larval detection in CFS and the brain lesions. Detection of larvae in the urine of infected horses has been also reported, suggesting that it can be a route of elimination to the environment, which is compatible with the abundant amount of nematode inside renal tubules found in the histopathology of this horse.7,12 This horse was dewormed with Ivermectin. Some reports suggest that this drug or the recommended dose to treat gastrointestinal parasites are not effective against H. gingivalis, and no other chemical therapies have been described for this infection.3,9,11

Contributing Institution:

Escola de Veterinária, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais – www.vet.ufmg.br

JPC >Diagnoses:

Kidney: Nephritis, granulomatous, chronic-active, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with adult and larval rhabditid nematodes and eggs.

JPC Comment:

This is a great example of a classic entity in horses. The contributor’s comment covers most of what was discussed regarding H. gingivalis. A few points of note from this conversation are that, as a reminder, the neutrophils most of our routine large animal species (equines and bovines, especially) are more eosinophilic that in small animals and can be mistaken for eosinophils. Remember, in horses, their eosinophils are prominent and look like raspberries! Additionally, H. gingivalis, al-though commonly associated with the oral cavity, facial bones, kidneys, and brain, can cause lesions anywhere throughout the body. Dr. Engiles told participants of a recent case she had of H. gingivalis infection in the cannon bone of a horse where the parasites had migrated into the bone hematogenously. The horse’s presenting complaint was just “lameness.” This was an important lesson in not pigeonholing oneself and remaining open-minded about possible diagnoses.

The genus Halicephalobus is derived from the Greek roots “hyalinos”, “kephalon”, and “lobos”, meaning “transparent head lobe”. This apparently refers to the clear, lobed head structure of the adult nematode seen on stereomicroscopy. You’ll have to ask the parasitologists on that one. For H. gingiavlis, the specific species epithet originates from its initial identification in the oral cavity of a horse. Stefanski was the first person to describe the nematode in 1954 when he found worms in a gingival granuloma in a horse in Poland.9 H. gingivalis has also been referred to as Micronema deletrix or H. deletrix over the years.2,9

In all cases of H. gingivalis in both humans and animals, only parasitic female adults, larvae, and eggs have been isolated from hosts. This strongly suggests that H. gingivalis can reproduce parthenogenetically, which is known to occur in other rhabditid nematodes. H. gingivalis is primarily considered a pathogen of horses and other equids but is also known to affect humans and was recently reported in ruminants.5,9 Transmammary infection from mare to foal has also been reported once.9

References:

- Adedeji AO, Borjesson DL, Kozikowski-Nicholas TA, Cartoceti AN, Prutton J, Aleman M. What is your diagnosis? Cerebrospinal fluid from a horse. Vet Clin Pathol. 2015; 44(1):171-2.

- Anderson RC, Under KE, Peregrine AS. Halicephalobus gingivalis (Stefanski, 1954) from a fatal infection in a horse in Ontario, Canada with comments on the validity of deletrix and a review of the genus. Parasite.1998; 5:255-61.

- Brojer JT, Parsons DA, Linder KE, Peregrine AS, Dobson H. Halicephalobus gingivalis encephalomyelitis in a horse. Can Vet J. 2000;41:559-61.

- Cunha BM, França TN, Miranda IC, Santos AM, Seixas JN, Pires APC, Santos BBN, Peixoto PV. Miocardite granulomatosa em cavalo por Halicephalobus gingivalis ( deletrix) - Relato de caso. Rev Braz Med Vet. 2016;38(2):113-16.

- Enemark HL, Hansen MS, Jensen TK, Larsen G, Al-Sabi MNS. An outbreak of bovine meningoencephalomyelitis with identification of Halicephalobus gingivalis. Vet Parasitol.2016;218:82-6.

- Isaza R, Schiller CA, Stover J, Smith PJ, Greiner EC. Halicephalobus gingivalis (nematoda) infection in a grevy's zebra (Equus grevyi). J Zoo Wild Med. 2000;31(1):77-81.

- Kinde H, Mathews M, Ash L, Leger JSt. Halicephalobus Gingivalis ( Deletrix) infection in two horses in southern California. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2000;12(2):162–5.

- Lim CK, Crawford A, Moore CV, Gasser RB, Nelson R, Koehler AV, Bradbury RS, Speare R, Dhatrak D, Weldhagen GF. First human case of fatal Halicephalobus gingivalis meningoencephalitis in Australia. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1768-74.

- Onyiche TE, Okute TO, Oseni OS, Okoro DO, Biu AA, Mbaya AW. Parasitic and zoonotic meningoencephalitis in humans and equids: Current knowledge and the role of Halicephalobus gingivalis. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2017 Dec 29;3(1):36-42.

- Pearce SG, Bouré LP, Taylor JA, Peregrine AS. Treatment of a granuloma caused by Halicephalobus gingivalis in a horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219(12):1735-8.

- Rames DS, Miller DK, Barthel R, Craig TM, Dziezyc J, Helman RG, Meale R. Ocular Halicephalobus (syn. Micronema) deletrix in a horse. Vet Pathol. 1995;32(5):540-2.

- Sant’Ana FJF, Júnior JAF, Costa YL, Resende RM, Barros CSL. Granulomatous meningoencephalitis due to Halicephalobus gingivalis in a horse. Braz J Vet Pathol. 2012;5(1):12-5.

- Taulescu MA, Ionicã AM, Diugan E, Pavaloiu A, Cora R, Amorim I, Catoi C, Roccabianca P. First report of fatal systemic Halicephalobus gingivalis infection in two Lipizzaner horses from Romania: clinical, pathological, and molecular characterization. Parasitol Res. 2015;115(3):1907-2103.

- Vasconcelos RO, Lemos KR, Moraes JRE, Borges VP. Halicephalobus gingivalis ( deletrix) in the brain of a horse. Cienc Rural. 2007;37(4):1185-7.