Signalment:

Gross Description:

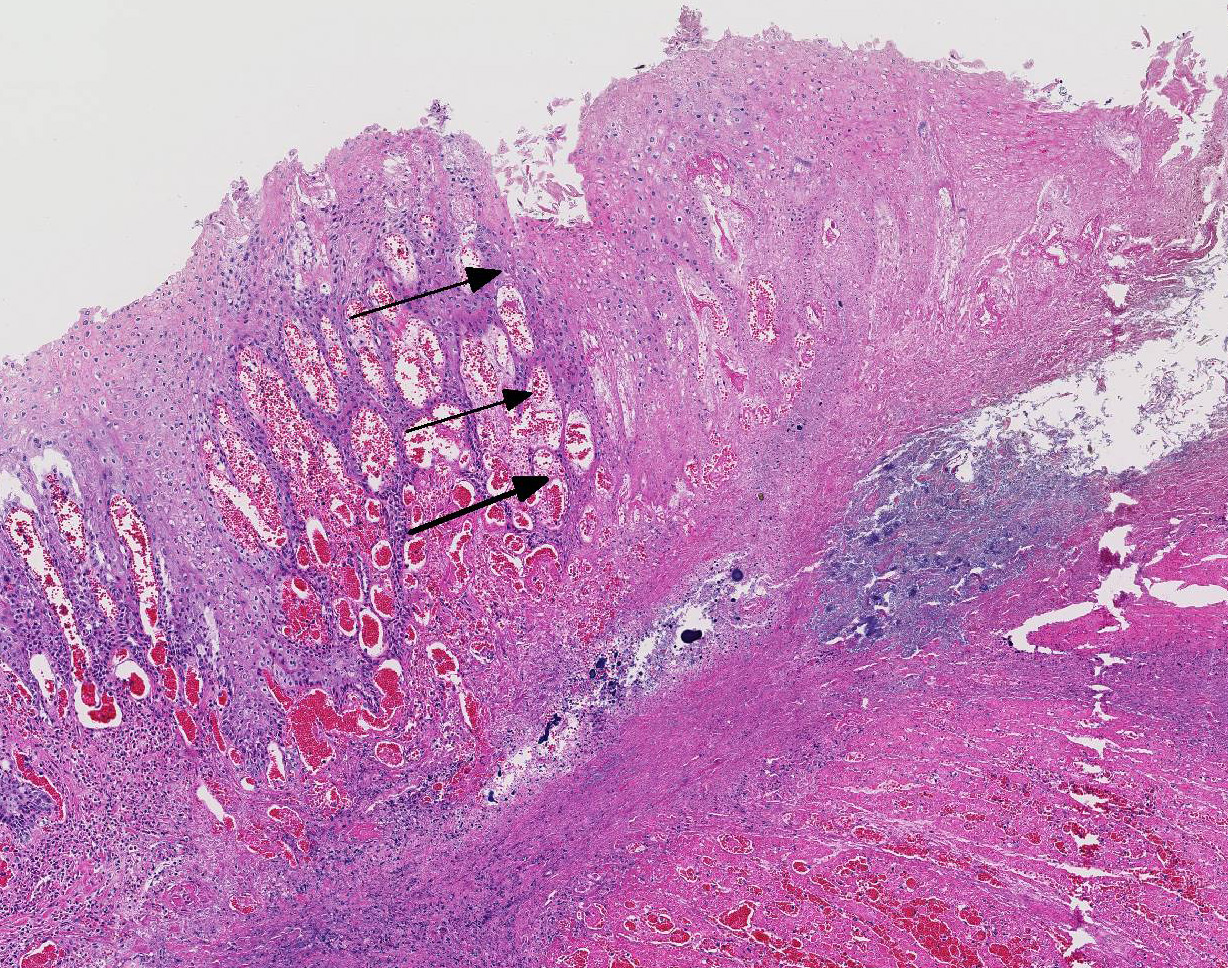

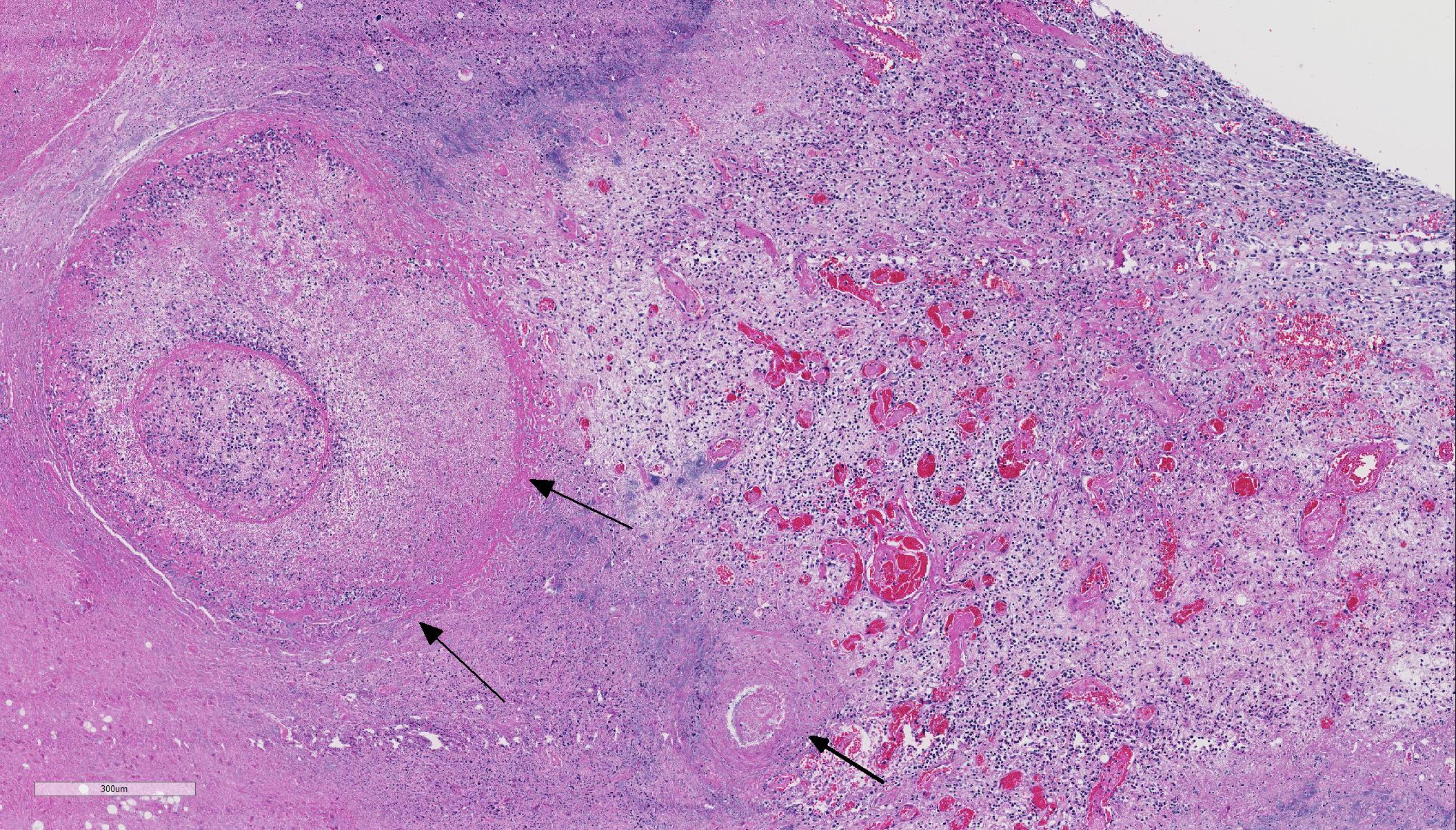

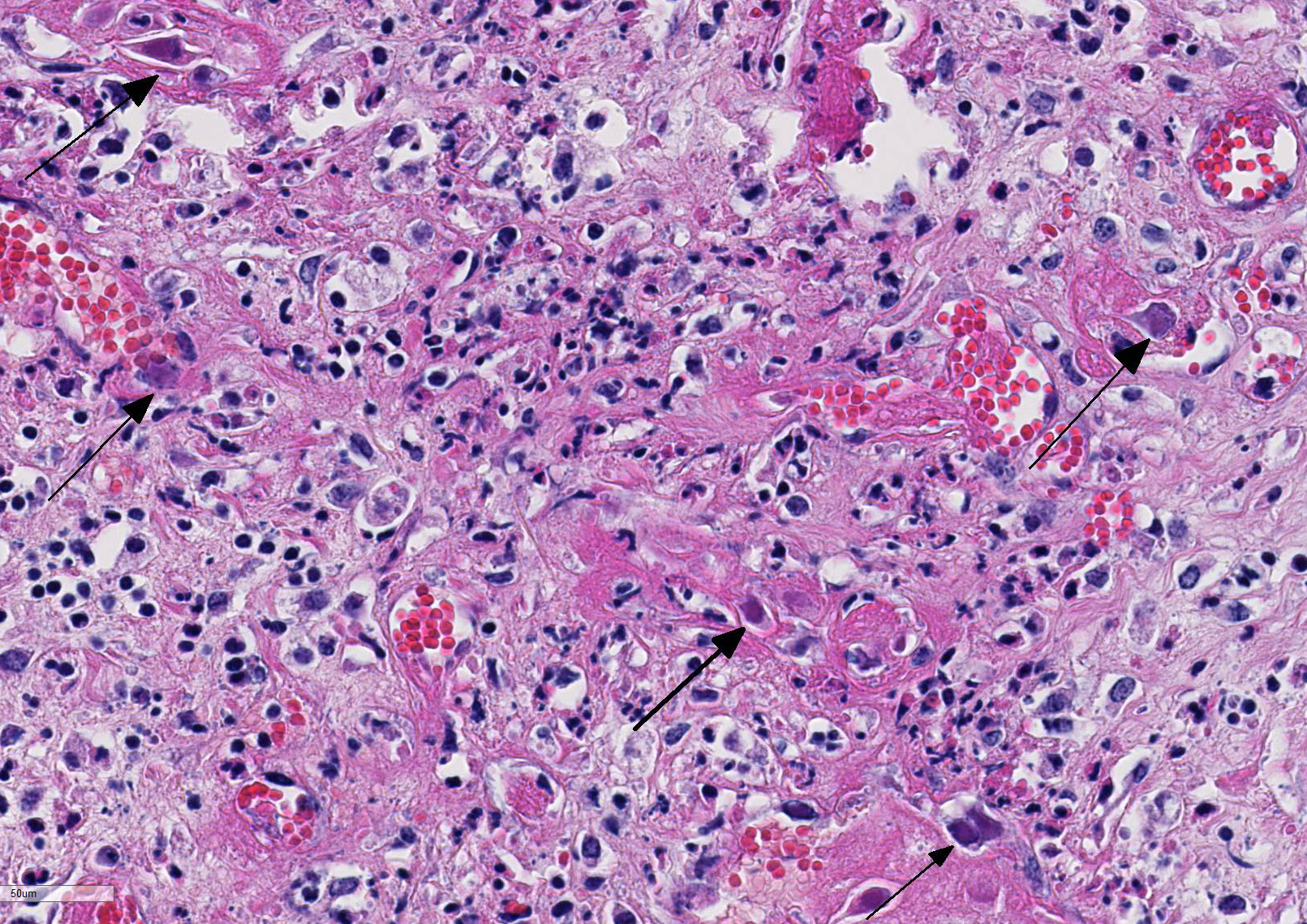

Histopathologic Description:

Microscopic diagnoses of tissues not submitted: Bronchopneumonia, suppurative and necrotizing, subacute, moderate, with mild lymphoid hyperplasia.

2. Lungs: Vasculitis, mild, subacute, multifocal (no viral inclusions detected).

3. Heart: Necrotizing myocarditis, multifocal, mild, acute (no viral inclusions detected).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Bovine viral diarrhea I&II PCR of lymph node: Negative

Aerobic culture of lung: Pasteurella multocida, heavy growth

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

As is true with other adenovirus infections, young animals experience a significantly higher morbidity and mortality rate when compared to adults.1,9,11 Death can occur as rapidly as five days post-infection, but chronic cases can also occur.12,13 Acute cases usually have no symptoms or may exhibit ptyalism, diarrhea (with or without blood), weakness, lethargy, anorexia, and edema.1,9,10 Chronic infections are usually associated with ulcers and abscesses of the mouth and throat, emaciation, and/or sepsis .1,13

Disease can be systemic or local.11 Typical necropsy findings of systemic infections include severe pulmonary edema expanding the interlobular septa with ecchymotic hemorrhages of the lungs and pulmonary artery, and a hemorrhagic enteropathy characterized by hemorrhage within the lumen of the small and large intestine.12,13 Additionally, multiple ulcerative lesions of the mouth, nasal cavity, mandible, maxilla, and forestomach can be present in systemic disease.11 Local disease is restricted to the upper alimentary tract (stomatitis, pharyngitis, mandibular/maxillary osteo-myelitis, and/or rumenitis).13 In either form, secondary bacterial infections are common, primarily presenting as abscesses of the oral and nasal cavities.12-15 Secondary bacterial agents include Trueperella pyogenes, Prevotella spp., Fusobacterium necrophorum, Streptococcus spp., Pasteurella multocida, and Pepto-streptococcus spp.12-15

Histologic findings of OdAdV are predominately associated with vascular changes, including endothelial hypertrophy, fibrinoid vascular necrosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and thrombosis, with resulting mucosal ulcerations, tissue infarctions, and extensive edema.10,11 All types of vessels can be affected and endothelial cell inclusions can be seen in any tissue, with or without significant vascular changes.12,13 Animals with infection localized to the upper alimentary tract, especially in more chronic infections, can lack endothelial intranuclear inclusions and viral detection methods may be ineffective.1,11,13 Diagnosis of adenovirus infection in cervids can be accomplished by histopathology with characteristic endothelial intranuclear inclusions,11 immunohistochemistry of infected tissue,12 enzyme-linked immuno-sorbent assay (ELISA),6 serum neutralization,13 virus isolation,11 immuno-fluorescence,11 and PCR (unpublished data).

Differential diagnoses for rumen ulceration include bluetongue (BT) and epizootic hemorrhagic disease of deer (EHD), which are both associated with widespread hemorrhage, edema, necrotizing vasculitis, thrombosis, and ulceration of the alimentary tract.10 Unlike acute adenovirus infection, inclusions are not detected in tissues with either of these diseases, and additional diagnostic testing may be necessary for definitive diagnosis.10 In this case, BT and EHD were considered unlikely based on the time of year, since the insect vector (Culicoides) is inactive during the winter in Colorado. However, in the warmer season and with chronic cases of OdAdV where inclusions may not be present, all three hemorrhagic diseases (BT, EHD, and AHD) should be considered. Additional differentials for rumen ulceration include mycotic rumenitis and rumen acidosis with Fusobacterium necrophorum infection (necrobacillosis).

In this case, the cause of death was likely multifactorial: malnutrition (emaciation), Pasteurella multocida infection, and OdAdV infection. Pasteurellosis is a known cause of mortality in elk calves and can result in rapid septicemia and death.3 For this animal, it was unclear if the pulmonary vasculitis and necrotizing myocarditis were related to P. multocida infection and bacterial sepsis, OdAdV, or both. Unfortunately, the definitive role of adenovirus as a primary pathogen in elk and/or a predisposition for other infectious organisms requires further investigation.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Conference participants discussed the top two differentials for necrotizing vasculitis causing severe hemorrhagic disease in elk and white-tailed deer. Bluetongue virus (BTV) and epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus (EHD) of the genus Orbivirus and family Reoviridae, mentioned by the contributor, are the top two differentials that must be considered in cases of widespread hemorrhage, necrotizing vasculitis, edema, thrombosis, and ulceration of the alimentary tract.1,2,4,10,11-15 EHD and BTV are both spread by the salivary secretions of the biting Culicoides spp. vector. In North America, EHD is the mist significant viral disease in the highly susceptible white-tailed deer, and devastating epizootics have been reported in the United States. Elk are generally less severely affected by BTV and EHD infection. Both BTV and EHD circulate throughout North America and outbreaks often occur simultaneously.10,11-15 Interestingly, both viruses can be concurrently isolated from the same individual Culicoides vector. Conference participants also noted that malignant catarrhal fever caused by ovine herpesvirus-2, a highly pathogenic gammaherpesvirus, can also produce intestinal hemorrhage, pulmonary congestion, edema, and petechiae of the spleen, intestines, heart, and liver with lymphocytic necrotizing vasculitis, and thrombosis in cervids and should also be considered as a potential differential in similar cases.7

The conference moderator mentioned that orbivirus infection will not produce the characteristic intranuclear viral inclusion bodies of adenovirus. To further differentiate these two diseases, orbiviral disease outbreaks are usually associated with acute onset of fulminant disease with high morbidity and mortality and viral tropism for the microvasculature endothelial cells. OdAdV typically results in a more chronic onset with targeting of the larger vessels and resulting in larger areas of coagulative necrosis.1,2,4,5,10-15 Additionally, petechial and/or ecchymotic hemorrhages present at the base of the pulmonary artery has been reported to be highly characteristic and potentially pathognomonic for orbivirus infection in susceptible species. As mentioned by the contributor, diagnosis of adenovirus infection is done by a combination of testing modalities, including visualization of the characteristic endothelial intranuclear inclusions with histopathology, immunohistochemistry (IHC), virus isolation, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).11

References:

1. Boyce WM, Woods LW, Keel MK, MacLachlan NJ, Porter CO, Lehmkuhl HD. An Epizootic of Adenovirus-Induced Hemorrhagic Disease in Captive Black-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus hemionus). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2000; 31:370-373.

2. Fox KA, Atwater L, Hoon-Hanks L, Miller M. A mortality event in elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) calves associated with malnutrition, pasteurellosis, and deer adenovirus in Colorado, USA. J Wildl Dis. 2017; 53(3): DOI: 10.7589/2016-07-167. [Epub ahead of print].

3. Franson, JC, Smith BL. Septicemic pasteurellosis in elk (Cervus elaphus) on the United States National Elk Refuge, Wyoming. J Wildl Dis. 1988;24:715717.

4. Gelberg HB. Alimentary system and the peritoneum, omentum, mesentery, and peritoneal cavity. In: McGavin JF, Zachary MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2017:325-375.

5. Lapointe, JM, Hedges JF, Woods LW, Reubel GH, MacLachlan NJ. The adenovirus that causes hemorrhagic disease of black-tailed deer is closely related to bovine adenovirus-3. Arch Virol. 1999;144:393-396.

6. Lapointe, JM, Woods LW, Lehmkuhl HD, et al. Serologic detection of adenoviral hemorrhagic disease in black-tailed deer in California. J Wildl Dis. 2000;36:374-377

7. Palmer MV, Thacker TC, et al. Active and latent ovine herpesvirus-2 (OvHV-2) infection in a herd of captive white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J Comp Path. 2013; 149:162-166.

8. Shilton CM, Smith DA, Woods LW, Crawshaw GJ, Lehmkuhl HD. Adenoviral infection in captive moose (Alces alces) in Canada. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2002;33:73-79.

9. Sorden SD, Woods LW, Lehmkuhl HD. Fatal pulmonary edema in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) associated with adenovirus infection. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2000;12:378380.

10. Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:131-140.

11. Woods, LW, Swift PK, Barr BC, et al. Systemic adenovirus infection associated with high mortality in mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in California. Vet Pathol. 1996;33:125-132.

12. Woods, LW, Hanley RS, Chiu PH et al. Experimental adenovirus hemorrhagic disease in yearling black-tailed deer. J Wildl Dis. 1997;33:801-811.

13. Woods, LW, Hanley RS, Chiu PH, et al. Lesions and transmission of experimental adenovirus hemorrhagic disease in black-tailed deer fawns. Vet Pathol. 1999;36:100-110.

14. Woods LW, Lehmkuhl HD, Swift PK, et al. Experimental adenovirus hemorrhagic disease in White-tailed deer fawns. J Wildl Dis. 2001;37:153158.

15. Woods LW, Lehmkuhl HD, Hobbs LA, Parker JC, Manzer M. Evaluation of the pathogenic potential of cervid adenovirus in calves. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008;20:3337.