Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 8, Case 3

Signalment:

17-year-old, female (spayed), domestic long hair, Felis catus, feline.History:

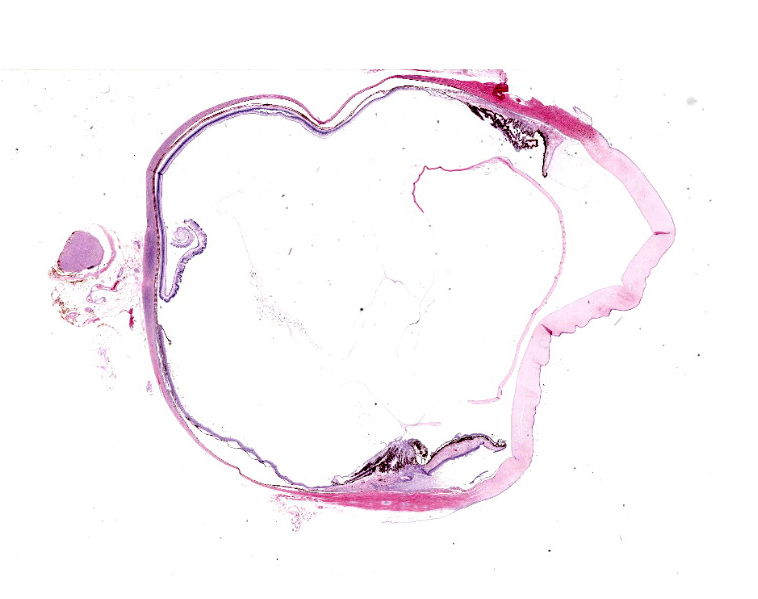

Gross Pathology: Intact globe OD submitted with no gross evidence of intraocular neoplasm.Laboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

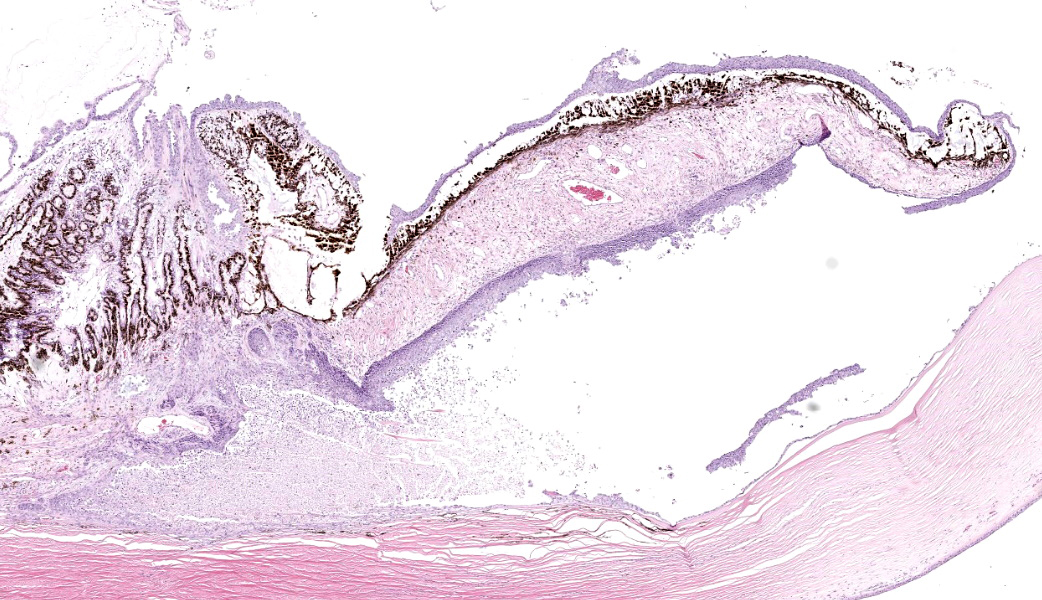

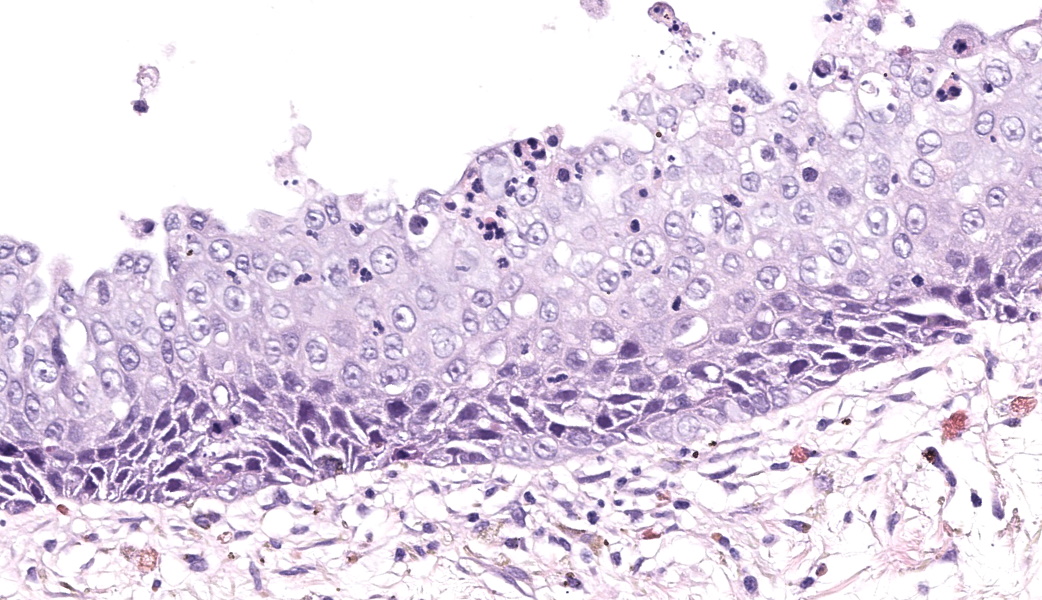

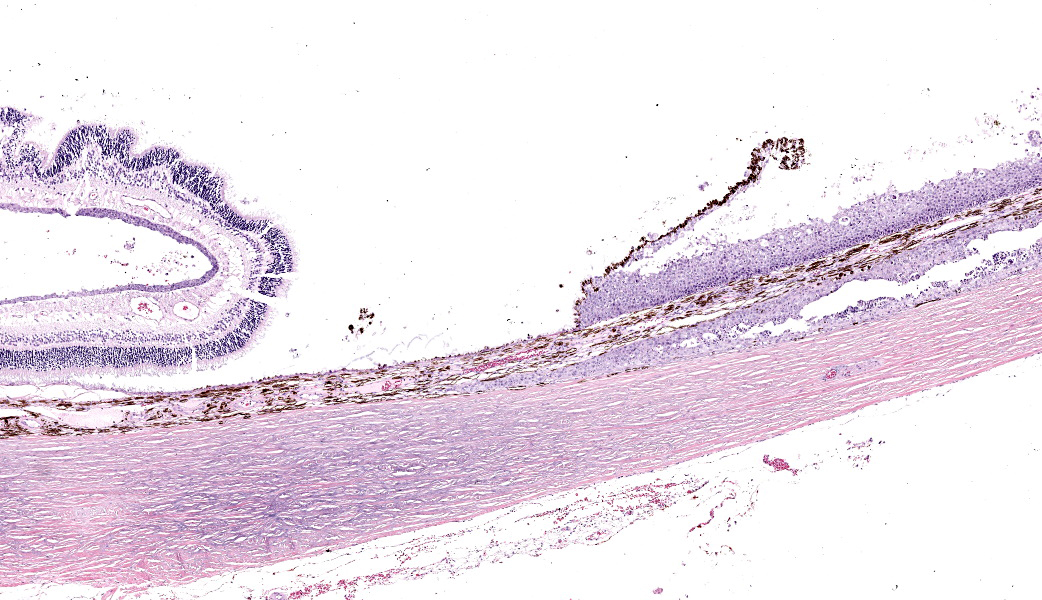

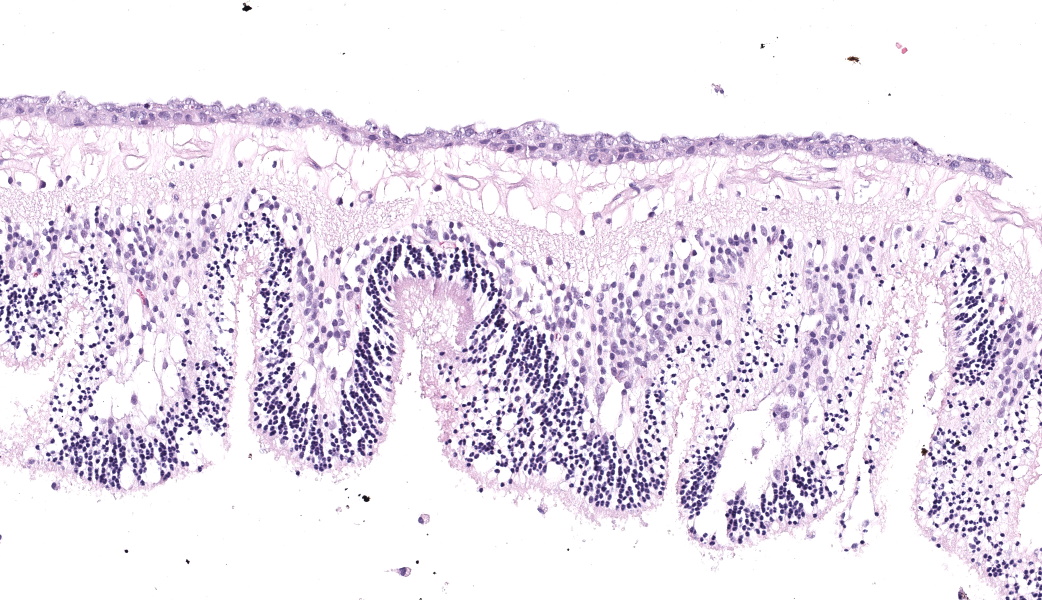

Eye: Overlying the corneal endothelium, anterior and posterior iris, portions of the lens epithelium, and the inner surface of the retina, as well as effacing and replacing the ciliary body, and occluding the drainage angle is an unencapsulated, densely cellular, infiltrative, neoplasm composed of epithelial cells arranged in broad dense cords on a moderate fibrovascular stroma. Neoplastic cells are polygonal with distinct cell borders, pronounced intercellular bridging, a moderate amount of pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, and irregularly round to vesiculate nuclei, with up to three distinct nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis is moderate. The mitotic rate is high with up to 12 mitotic figures per ten 40x HPF. Multifocally, neoplastic cells exhibit squamous differentiation. Near the optic nerve, the neoplastic cells invade the vascular and fibrous tunics, elevating and dissecting beneath the retinal pigment epithelium under a detached and coiled degenerate retina. At the caudal interior surface of the globe, there are numerous neutrophils admixed with abundant eosinophilic cellular and karyorrhectic debris and neoplastic cells infiltrate into the retinal vasculature.Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Eye: Squamous cell carcinoma, domestic long hair, Felis catus, feline.Contributor's Comment:

Generally, neoplasms within the globe may be (1) primary (arising from one of the intraocular tissues), (2) secondary (invading the globe from an adjacent tissue), or (3) metastatic (arising via hematogenous dissemination of a distant malignancy).2 Many ophthalmic tumors are histologically benign but are locally invasive and, within the confined space of the eye or orbit, can produce significant tissue distortion.5Surgical definitions which may be relevant when communicating with clinicians include: evisceration, which is the removal of the cornea and the internal contents of the eye while leaving the scleral shell of the globe and eye muscles behind; enucleation, which is the removal of the entire globe while leaving muscles that control eye movement and other orbital contents intact; and exenteration, which is the total removal of the globe and all surrounding tissues including eyelids, muscles, nerves and fatty tissues from the orbit.

Primary intraocular neoplasia. Uveal melanocytic neoplasia (“diffuse iris melanoma” in cats and “canine anterior uveal and epibulbar melanoma/melanocytoma” in dogs) is the most common primary intraocular neoplasm, occurring roughly three times as frequently as ciliary body epithelial neoplasms in dogs and ten times as frequently as ciliary body epithelial neoplasms in cats.1-2,5 This neoplasm typically originates on the anterior surface of the iris, producing multifocal areas of pigmentation with a high potential for local invasion into the ciliary body and the iridocorneal angle.5 Common presenting clinical signs in affected cats includes hyperpigmentation of the iris, pupillary deficits, buphthalmia resulting from secondary glaucoma, and evidence of uveitis.5 Extension posteriorly to affect the choroid is rare.5 Anterior uveal melanocytomas and melanomas may extend along the anterior or posterior scleral emissaria into and through the sclera to involve the periocular tissues, and the optic nerve provides routes of egress for neoplasms in the posterior pole, but extraocular extension does not always correlate with a poor prognosis.2 Only malignant uveal melanomas and schwannomas in dogs and diffuse iris melanoma and ocular sarcomas in cats carry significant metastatic risk.2 The regional lymph nodes, liver, and lungs are the principal sites for melanoma metastasis.5 Other primary intraocular neoplasms are uncommon and include posttraumatic sarcomas of cats and rarely other species such as the rabbit, schwannomas of blue eyed dogs, astrocytomas, and primary neuroectodermal neoplasms including medulloepitheliomas and retinoblastomas in varied animal species.2 With few exceptions, the majority of primary intraocular neoplasms remain restricted to the globe and timely enucleation is curative.2 As the globe lacks lymphatics, metastasis from the intraocular tissues will be hematogenous and occurs either through the scleral venous plexus subsequent to invasion of the trabecular meshwork and sclera, or tumor invasion of the uveal and retinal vasculature.1-2

Secondary intraocular neoplasia. Aggressive malignancies of adjacent tissues may invade the eye and uvea through the cornea, sclera, or optic nerve.2 Scant descriptive literature is available; secondary neoplasia is most commonly encountered with squamous cell carcinoma of cow, horse, and cat, and nasal adenocarcinomas with orbital extension in dogs.2,4 A myxosarcoma involving the optic disc was most likely an extension from the orbit and optic nerve.2 Meningiomas of the optic nerve may extend through the lamina cribrosa into the globe.2 Other feline orbital neoplasms include zygomatic osteoma, parosteal osteoma, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, undifferentiated sarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma.4

Metastatic intraocular neoplasia. It is not surprising that the extensive vascular network of the uvea renders it a prime site for metastatic disease from primary malignancies elsewhere; incidence of metastasis to the eye is less than primary uveal neoplasms but more frequent than implied by the scant literature as the majority of animals dying of widespread metastatic disease are not subjected to thorough ophthalmic clinical, postmortem, and histopathologic examinations.2 Intraocular lymphosarcoma is the most common metastatic neoplasm in the dog and cat, with shared clinical and histopathologic presentations.1,2,4 In dogs, these neoplasms occurred bilaterally, predominantly in the anterior uvea, and were diffuse large B-cell, T-lymphoblastic, peripheral T-cell not otherwise specified, and lymphocytic B-cell lymphomas.1 In cats, feline leukemia virus (FeLV)-associated T-cell lymphoma was the most common.1 Mammary carcinoma was the second most common ocular metastatic neoplasm in bitches, with a predominantly unilateral involvement of the uveal tract.1 Clinically and by gross examination, intraocular lymphosarcoma is a masquerader and may manifest as unilateral or bilateral uveitis, keratitis, retinal detachment, intraocular hemorrhage, and glaucoma, with or without observable proliferative lesions.2,4 Not uncommonly, the ocular manifestations may be the presenting sign of occult systemic disease and globes are frequently enucleated due to complicating factors but with a suspicion of intraocular neoplasia.2,4 Typical ocular presentation of lymphosarcoma in cats is a nodular iridal mass.3 The question “does unicentric intraocular lymphoma exist” often has been asked, and the response is “probably not,” with disease developing elsewhere over time.2 Additional feline tumors that are known to metastasize to the eye include fibrosarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma, mammary adenocarcinoma, uterine adenosarcoma, and adenocarcinomas of undetermined origin.4 In cats, following lymphoma, pulmonary and squamous cell carcinomas were the most common multicentric/metastatic neoplasms of the eyes.1 Pulmonary carcinoma is unusual in its capacity to colonize the vascular endothelium of choroidal retinal arteries.4 Individual cases of cholangiocarcinoma, hemangiosarcoma, and chemodectoma in the dog, as well as individual cases of mammary gland cribriform carcinoma, salivary gland carcinoma, and histiocytic sarcoma in the cat have been reported.1

Conclusion. It is a common belief among specialists in veterinary and human ocular pathology that squamous cell carcinoma cannot originate from within the globe. (J.S. Estep, personal communication; December 26, 2019) Therefore, finding squamous cell carcinoma within the globe of a living patient should prompt the pathologist to warn clinicians to perform a thorough search for the primary neoplasm elsewhere.

Contributing Institution:

Texas Veterinary Pathology Associates https://texasvetpath.com/index.htmJPC Diagnoses:

Globe: Metastatic carcinoma.JPC Comment:

This case contributor gives a thorough review of intraocular neoplasms in cats, touching on many major points of discussion during review of this case. Conference participants were readily able to reach a diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma, but not all were convinced that this was a metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) due to the lack of dyskeratosis within neoplastic epithelial cells, coupled with the lack of a primary mass found during workup. The prominent intercellular bridging between the neoplastic cells was noted by all, which can be a major feature of SCC; and squamous cell carcinomas are common tumors of the feline head; however other participants felt strongly that they could not rule out a carcinoma of other origin based on histology alone. For this reason, a morphologic diagnosis of “metastatic carcinoma” was ultimately favored by participants in this case due to the lack of clear-cut evidence of a squamous cell carcinoma on the H&E.There was no argument to be found on whether this was primary or metastatic, as the histologic evidence was strongly supportive of a metastatic process (i.e., the neoplasm primarily found within the highly vascular choroid and uvea, intravascular neoplastic cell emboli, etc.). The secondary changes in the eye were also discussed and it was concluded that this eye had glaucoma secondary to the neoplasm, evidenced by the retinal ganglion cell degeneration and loss with tapetal sparing, occlusion of the drainage angles by both the neoplasm and inflammation, buphthalmia (enlarged globe, attenuated and degenerative corneal epithelium, scleral thinning), and perivascular edema of the aqueous veins that drain the trabecular meshwork of the drainage angle.

During conference, yet another opportunity arose to briefly discuss common intraocular neoplasms of cats. Key nuggets from this discussion include the fact that cats can develop primary uveal schwannomas similar to those seen in blue-eyed dogs, the most common metastatic neoplasm of the eye in cats is lymphoma, and most other metastatic tumors to the eye in cats are carcinomas that most often affect the posterior uvea.1,2

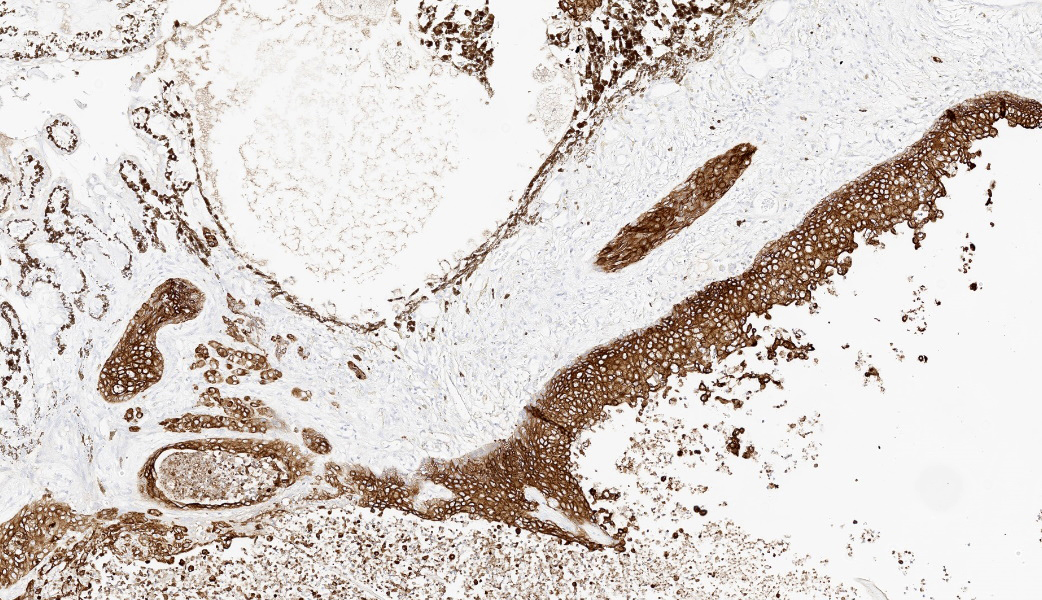

In keeping with her “games” theme, MAJ Fiddes put participants through a few rounds of “I Spy” during this case, focused entirely on the pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3) immunohistochemical stain run on this case and a few issues spotted therein. The first issue was that, while the neoplastic cells had strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity to pancytokeratin, the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) was diffusely unreactive. As it turns out, RPE is specifically reactive for CK8/18, and the pancytokeratin cocktail used by the JPC does not include these. Instead, CK8/18 is offered as a stand-alone IHC here, and its absence in the pancytokeratin would explain why the RPE was not reactive. The second issue was that the neural fibers of the optic nerve had diffuse reactivity to pancytokeratin. That’s weird, why would neural tissue be reactive to cytokeratins? Well, as fate would have it, it’s not. Pancytokeratin and GFAP are cross-reactive. GFAP is not cross-reactive with most individual cytokeratins, but is to pancytokeratin, making neural tissue appear immunoreactive to AE1/AE3!3 Between AE1 and AE3, it is the AE3 component specifically that contributes to this cross-reactivity.3 This has been demonstrated in brain and glial tissues, as well as in some retroperitoneal schwannomas. As such, interpretation of cytokeratin expression in neural tissue, including neoplasms of neural origins, should be cautiously interpreted.3 This “I Spy” game was a poignant reminder that pathologists should scrutinize IHCs and ensure good external and internal control prior to reading them out, and knowledge of what reacts to what can be critical to appropriate interpretation.

References:

- Bandinelli MB, Viezzer Bianchi M, Wronski JG, et al. Ophthalmopathologic characterization of multicentric or metastatic neoplasms with an extraocular origin in dogs and cats. Vet Ophthalmol. 2020;23(5):814-827.

- Grahn B, Peiffer R, Wilcock B. Intraocular neoplasia. In: Histologic Basis of Ocular Disease in Animals. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2019:409,433,435-436.

- Kriho VK, Yang HY, Moskal JR, Skalli O. Keratin expression in astrocytomas: an immunofluorescent and biochemical reassessment. Virchows Arch. 1997;431(2):139-47.

- La Croix NC. Ocular manifestations of systemic disease in cats. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2005;20(2):121-128.

- Willis AM, Wilkie DA. Ocular oncology. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2001;16(1):77-85.