Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 7, Case 3

Signalment:

A 13-year-old, neutered male, German Shepherd dog (canis familiaris)

History:

The patient had a history of hip dysplasia clinically diagnosed when the animal was 7-years-old and a fully excised mast cell tumor when this dog was 10-years-old. This animal always had good body condition. Animal was found dead without premonitory signs.

Gross Pathology:

The body had good post mortem preservation and good nutritional status, with ample deposits of adipose tissue in the subcutis and body cavities. There were large amounts of fibrin and alimentary contents in the abdominal cavity. In the gastric wall, a focal perforated transmural ulcer was identified in the fundic area. The lungs were red and wet. The myocardium was slightly pale and the coronary blood vessels visible on the epicardium were thickened with a yellow, irregular plaque-like lesions. No significant findings in other internal organs.

Microscopic Description:

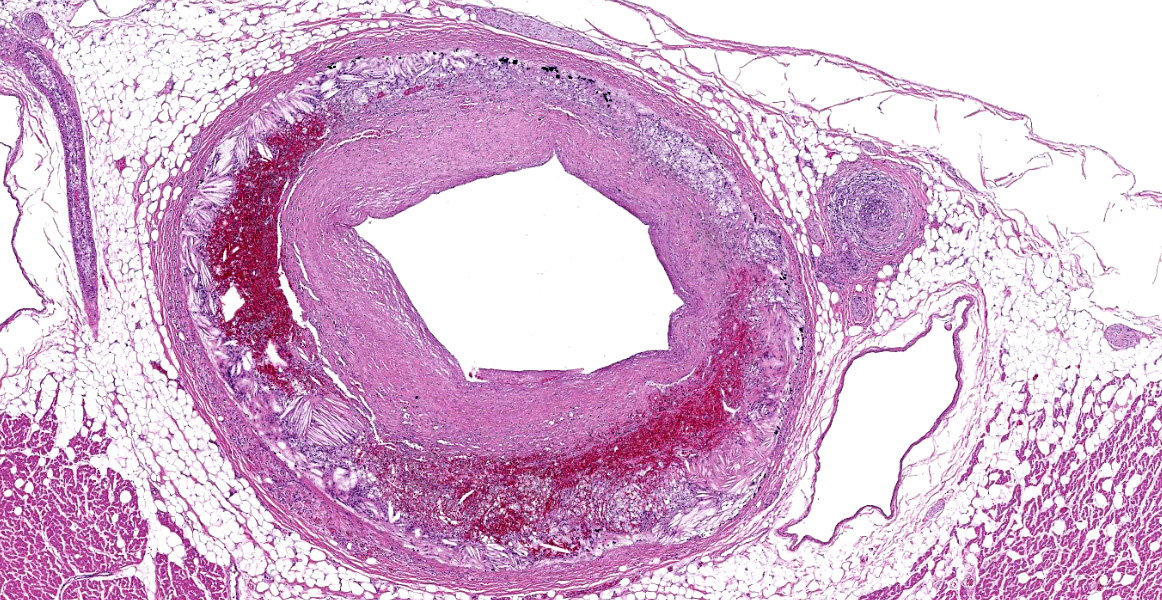

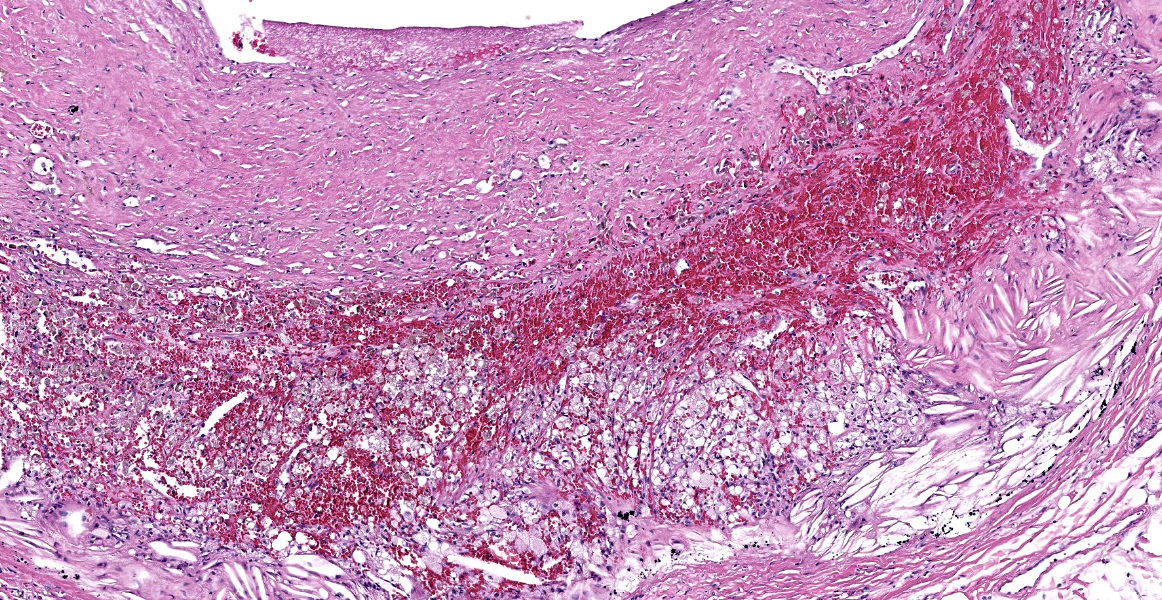

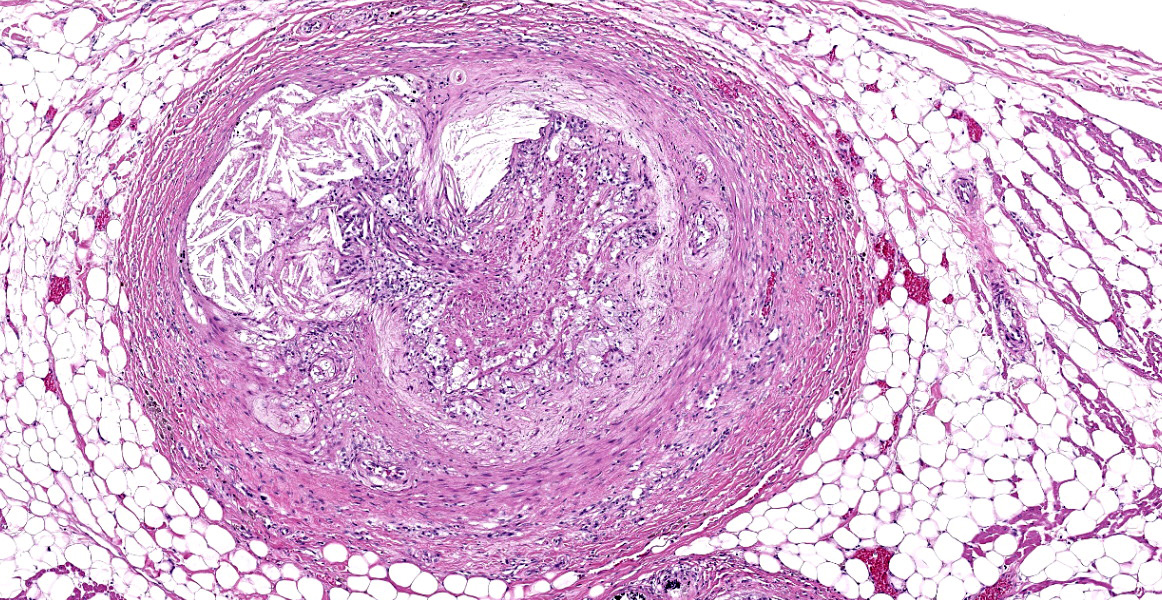

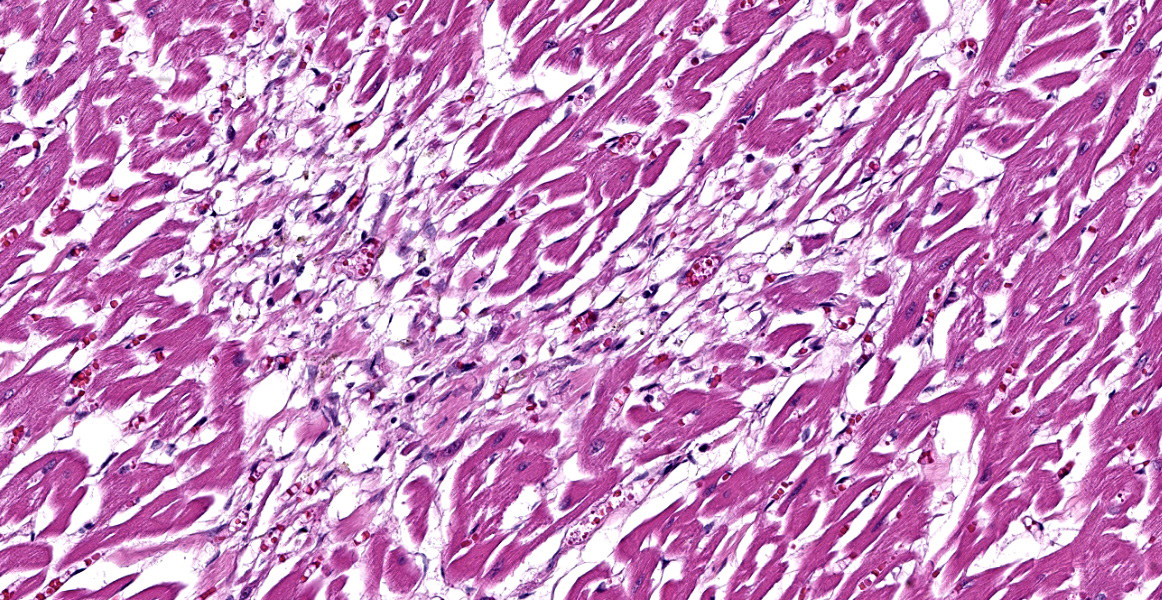

Heart, right and left ventricle: The most significant findings were identified in large and medium size arteries located in all layers of the heart. They all exhibit severe atheromatosis, characterized by the presence of numerous cholesterol clefts and foamy macrophages within the sub intima and/or in the adventitia of the vessels. In these areas, there are variable amounts of fibrin within the sub intima (fibrinoid necrosis) and also attached to the endothelial surface (thrombosis), and extensive hemorrhages and numerous hemosiderin laden macrophages. Some vessels are completely occluded with this inflammatory reaction. In the myocardium, multifocal areas of interstitial fibrosis are noted. In the sample collected from the right ventricle, there are numerous adipocytes tracking along the vessels in the myocardium (likely as a reflection of body condition).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis: Heart: Atherosclerosis, severe, multifocal, with foamy macrophages, cholesterol clefts and multifocal mild myocardial fibrosis.

Contributor’s Comment:

Multiple vessels in different organs (including the stomach, kidney, brain, lung, liver and small intestine) displayed atherosclerosis. This vascular lesion probably predisposed to an area of gastric ischemia/hypoxia, with consequent necrosis and rupture of the stomach. The cause for atherosclerosis in this patient could not be elucidated, due to the absence of antemortem blood studies. No significant gross or histologic findings were identified in the thyroid gland, adrenal gland, or pancreas.

Atherosclerosis is defined as a focal or multifocal thickening of the arterial walls due to the deposition of lipids, forming plaques.6,7 This condition has been associated with hyperlipidemia, which is defined as an elevation of plasma concentration of triglycerides and/or cholesterol. Hyperlipidemia can be physiologic or pathologic. Physiologic hyperlipidemia is frequently observed after meals (post prandial). Pathologic hyperlipidemia is associated with cholestasis, high fat diets, drug administration, nephrotic syndrome, lymphoma or endocrinopathies, such as hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism and diabetes mellitus.5,9,11

In domestic species, rabbits, chickens and pigs ae considered “atherosensitive”, whereas dogs, cats, ruminants and rats are considered “atheroresistant”.9 In dogs, atherosclerosis is almost always present in association with hypothyroidism or diabetes mellitus, although canine hypertension and obesity has also been associated with this condition. Spontaneous atherosclerosis has also been described but is considered extremely rare.5

The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis is not completely nor well understood.2 Dogs with hypothyroidism have increased very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), low density lipoproteins (LDL) and high-density lipoproteins (HDL). Dogs with diabetes mellitus have increased VLDL and HDL, and dogs with hyperadrenocorticism have increased LDL.1 As a result of hyperlipidemia, endothelial injury/dysfunction may occur.9 Endothelial cell dysfunction is defined as non-adaptive alteration in functional phenotype, which are fundamental in the regulation of hemostasis and thrombosis, local vascular tone, redox balance and inflammatory reaction. This dysfunction allows focal permeating, trapping and physicochemical modifications of circulating lipoprotein particles in the subendothelial space.10 This sequence of events leads to platelet adhesion, monocyte adhesion and infiltration, and insudation of lipid, as extracellular lipid or as intracellular lipid in “foam cells”. In addition, multiple growth factors and chemokines are generated by activated macrophages and endothelial cells, which activate smooth muscle cells and their precursors to promote their proliferation and synthesis of extracellular matrix in the intimal compartment. In one individual, numerous atherosclerotic plaques can coexist, and each has their own pathobiological evolution.4,9

The histopathologic lesion of atherosclerosis in dogs differs from the human counterpart, as the lesion in dogs has been described to begin in the middle and outer layers of the media and is much more frequent in small muscular arteries. The deposition of lipids in the internal layers of the media can promote disruption of the internal elastic lamina and involvement of the intima. In humans, atherosclerosis is primarily present in the intima and may extend to the tunica media and adventitia.9 Veins are not affected. Reports of immunohistochemical analysis of the atheromatous plaques in dogs conclude that lipids in the lesions contained low density lipoproteins, so they have similar features to human atherosclerotic lesions.6

Grossly, the lesions are identified as multifocal, sometimes confluent, yellow brown nodules in arterial walls in different organs. The heart, kidney and brain are usually more severely involved.9 Miniature Schnauzers (particularly females) and Shetland sheepdogs are predisposed to primary hyperlipidemia and are considered to be breeds with high risk for developing atherosclerosis.8

Atherosclerosis can be confirmed by histopathology. Nevertheless, because of invasiveness of sampling, the use of diagnostic imaging (CT scanner) may be used to assess the antemortem presence of calcified atheromatous plaques and degree of damage. This technique is useful in animals without evidence of metastatic calcification or endocrinopathy.7

Contributing Institution:

Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology

Virginia Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

205 Duck Pond Drive

Blacksburg, VA 24061.

https://vetmed.vt.edu/departments/biomedical-sciences-and-pathobiology.html

JPC Diagnosis:

Heart: Atherosclerosis, chronic, diffuse, severe with multifocal cardiomyocyte loss and fibrosis.

JPC Comment:

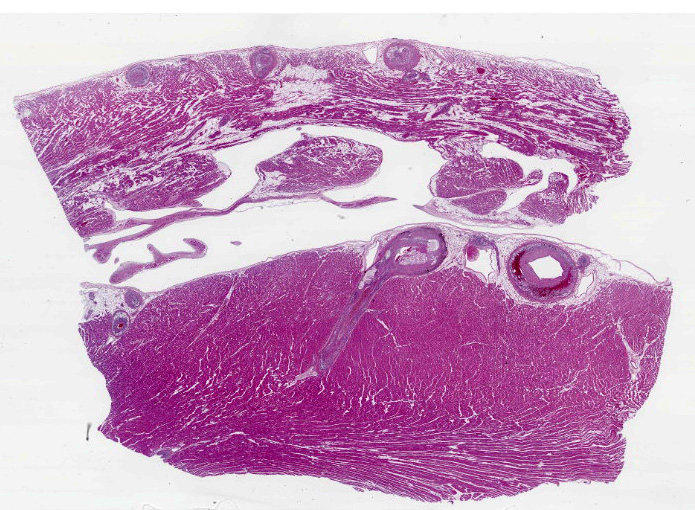

The contributor provides a detailed look at atherosclerosis that accompanies a great gross photo (figure 3-1) and a nice histology slide as well. The changes within muscular arteries are superb and are conveniently laid out both in cross-section and longitudinal section with a constellation of changes to appreciate (figures 3-2, 3-3, 3-4). Conference participants were also interested in the infiltration of adipocytes within the right ventricle and discussed the ultimate genesis. While arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is a good differential for this case due to the concurrent fibrous and fatty appearance of this section, myocytes lack active degeneration/necrosis that would be expected with ARVC. Instead, another potential explanation for these changes is ischemic injury to myocytes with loss and fibrosis – the infiltration of adipocytes in a generously apportioned (syn: extremely well-fed) reflects a race to see which entity will fill the empty space up first.

We ran Movat’s and Masson’s chromatic stains to characterize vascular and perivascular changes in this case. There is narrowing to complete occlusion of the vascular lumina (figure 3-5) with marked disruption of the tunica intima to include a focal area with fibrin and hemorrhage that may represent a true rupture of the coronary artery. Recently, a similar case of atherosclerosis was reported in a dog that lacked a history of endocrinopathy with distribution of lesions centered solely on the abdominal aorta and renal vasculature.3 The only clinical signs attributable in that presentation however were a history of hindlimb paresis and elevated renal values; primary cardiac lesions were absent grossly and histologically. Lastly, the distribution of lesions in this case (primarily subintimal) should be contrasted with atherosclerosis in birds where the lesions occur primarily within the intima as stiff plaques. For an example of recent WSC, refer to Conference 6, Case 1, 2023-2024 for a contrasting case in a saker falcon.

References:

- Barrie J, Watson TDG, Stear MJ et al. Plasma cholesterol and lipoprotein concentrations in the dog: The effects of age, breed, gender, and endocrine disease. J Sm Anim Pract. 1993; 34: 507-512.

- Boynosky NA, Stokking L. Atherosclerosis associated with vasculopathic lesions in a golden retriever with hypercholesterolemia. Can Vet J. 2014; 55: 484-488.

- Gimbrone MA Jr, García-Cardeña G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016; 118: 620-636.

- González-Domínguez, A, Tormo JR, Herrería-Bustillo, VJ. Aortic thrombosis and acute kidney injury due to atherosclerosis in a dog. JAVMA. 2024; 262(8):1-4.

- Hess RS, Kass PH, Van Winkle TJ. Association between diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism or hyperadrenocorticism, and atherosclerosis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2003; 17: 489-494.

- Kagawa Y, Hirayama K, Uchida E et al. Systemic atherosclerosis in dogs: histopathological and immunohistochemical studies of atherosclerotic lesions. J Comp Pathol. 1998; 118: 195-206.

- Lee E, Kim HW, Bae H, et al. Radiography and CT features of atherosclerosis in two miniature Schnauzer dogs. J Vet Sci. 2020; 21: e89.

- Mori N, Lee P, Muranaka S, et al. Predisposition for primary hyperlipidemia in miniature Schnauzers and Shetland sheepdogs as compared to other canine breeds. Res Vet Sci. 2010; 88: 394-399.

- Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:1-101.

- Simionescu N, Vasile E, Lupu F, et al. Prelesional events in atherogenesis. Accumulation of extracellular cholesterol-rich liposomes in the arterial intima and cardiac valves of the hyperlipidemic rabbit. Am J Pathol. 1986; 123: 109-25.

- Watson TDG, Barrie J. Lipoprotein metabolism and hyperlipidaemia in the dog and cat: A review. J Sm Anim Pract. 1993; 34: 479-487.