Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

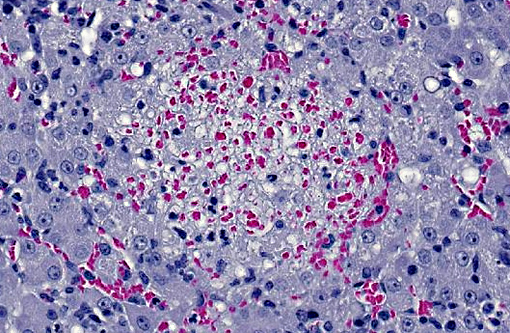

LIVER: Multifocally disrupting the hepatic parenchyma are low numbers of randomly scattered, variably sized foci of lytic necrosis characterized by loss of normal hepatic architecture and replacement by karyorrhectic debris, eosinophilic fibrillar material (fibrin), scattered erythrocytes and occasional degenerate neutrophils. Hepatocytes around the margins of necrotic foci are often swollen with vesicular nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm (degenerate). Moderate numbers of neutrophils, macrophages and fewer lymphocytes separate foci of necrosis from the surrounding normal hepatic parenchyma. Smaller foci of similar inflammatory cells without significant central necrosis are also scattered throughout. Faintly visible, slender, 4-20 μm long bacilli are rarely visible arranged in sheaves and stacks within degenerate and intact hepatocytes surrounding foci of inflammation and necrosis.

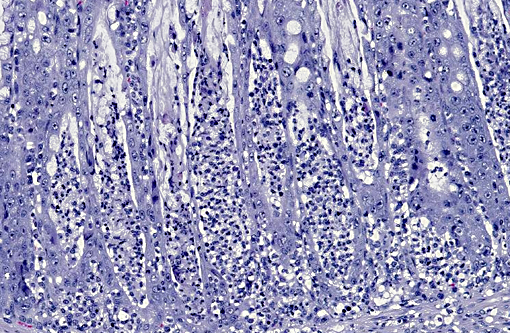

PROXIMAL COLON: The mucosa is multifocally eroded, with affected areas overlain by mats of bacteria admixed with karyorrhectic debris, mucin and degenerate neutrophils. Enterocytes are multifocally hypereosinophilic, rounded up and dissociated with pyknotic nuclei (necrosis). There is diffuse goblet cell hyperplasia. Colonic crypts contain excess mucin within which large numbers of faintly basophilic bacilli are often visible. In addition crypts multifocally contain karyorrhectic debris and degenerate neutrophils (crypt abscesses). Crypt enterocytes are multifocally crowded, with slightly basophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei and increased mitotic figures (regeneration). Moderate numbers of neutrophils and macrophages and fewer lymphocytes and plasma cells diffusely expand the lamina propria, multifocally extend into the submucosa, and rarely infiltrate the tunica muscularis.

OTHER TISSUES (not present on submitted slides): Similar, but less severe lesions to those in the colon are present in sections of ileum. A small focus of myocardial necrosis and neutrophil infiltration disrupts the left ventricular myocardium. Alveoli within the lungs diffusely contain lightly eosinophilic homogeneous material (oedema).

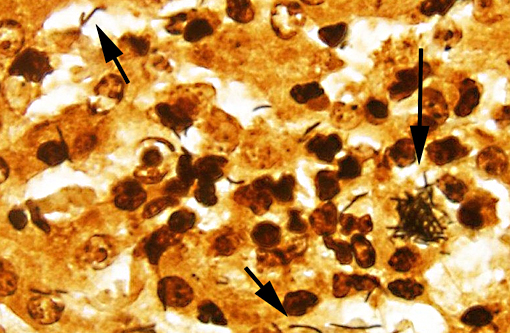

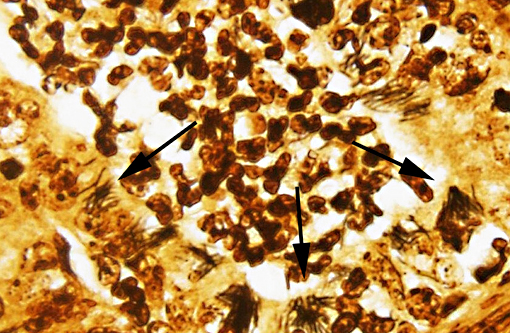

SPECIAL STAINS: Low to moderate numbers of slender, silver positive, 4-20 μm long bacilli arranged in criss-crossed stacks are visible within hepatocytes surrounding foci of necrosis in the liver on Warthin-Starry stained sections. The bacteria are difficult to discern with Gram stain. Myriad silver positive, 4-20μm long bacilli arranged in sheaves and crisscrossed stacks are visible within colonic crypts and within crypt enterocytes, and occasionally within the lamina propria on Warthin-Starry stained sections.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

LIVER: Moderate, subacute, multifocal, necrotizing and suppurative hepatitis with intracellular argyrophilic bacilli.

COLON: Severe, subacute, multifocal, necrotizing and suppurative colitis with crypt abscesses, goblet cell hyperplasia and myriad intralesional argyrophilic bacilli.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Tyzzers disease is a commonly fatal disease of primarily young animals caused by the gramnegative anaerobe Clostridium piliforme. Spontaneous disease is reported in a range of wild(9,10) and domestic(4,5,6) species, but is particularly well-recognized in laboratory animals (mice, rats, rabbits, gerbils, hamsters and guinea pigs)(8) and foals.(1) Rare cases are reported in cats.(4,7) Disease usually occurs as isolated cases or epizootics with low morbidity and high mortality. Antemortem clinicopathologic findings vary between species. Reports in kittens describe diarrhea, emaciation and depression,(4) while foals developed lethargy, recumbency, fever and seizures, metabolic acidosis, hypoglycemia and increased liver enzymes.(1) Definitive diagnosis is often possible based on characteristic gross and histologic lesions, with silver-positive bacterial rods visible in histological sections of affected liver. Serological tests, PCR and EM have also been utilized in the diagnosis.(1,4,5,9) The organism is extremely fastidious and culture is unrewarding.(7)

Among rodents, B6 mice are resistant to infection compared to CBA/N and DBA/2 mice, and Blymphocyte function appears to be particularly important in disease resistance.(8) Infected rats may develop a characteristic megaloileitis.(8) Gerbils are recognized to be highly susceptible to Tyzzers disease and are a useful sentinel animal to detect its presence in research facilities.(8) In rabbits, outbreaks are characterized by profuse diarrhea and high mortality among weanlings. Surviving animals may develop stenosis of the intestinal tract.(8)

The pathogenesis of Tyzzers disease is only partially elucidated. It is thought that rodents and rabbits may be an important source of infection through shedding of spores in feces.(8,12) The spores may remain infective in contaminated environments for up to a year.(8) Ingested spores are carried through the digestive tract into the small intestine and are able to penetrate mucosal epithelial cells and replicate within them.(12) Bacteria may reach the liver by penetrating capillaries within the lamina propria that drain into the portal venous system, or within macrophages (leukocyte trafficking).(12) Once in the liver, the bacteria penetrate sinusoidal endothelial cells and adjacent hepatocytes and replicate within them.(12) Lysis of infected cells results in the characteristic areas of lytic necrosis, which may be seen grossly as multiple 2-3mm yellow-grey foci scattered throughout the hepatic parenchyma.(8,12)

Predisposing factors are an important consideration and are frequently reported in cases of Tyzzers disease.(3,4,6,8) Stress associated with weaning, overpopulation, poor hygiene, immunosuppression due to disease or corticosteroid treatment, and concurrent infections are possible contributing factors.(8) Kittens with Tyzzers disease in one report were co-infected with feline panleukopenia virus.(4) In reports of Tyzzers disease in dogs, previous or concurrent infection with distemper, parvovirus and coccidia were described and likely contributed to susceptibility to Tyzzers.(3,6)

No significant concurrent disease processes were noted in the present case, but the history of diarrhea and recovery in other kittens from the pet store suggest the possibility of an underlying infectious enteritis that was not detected by routine diagnostic screening. The stress of transport and re-homing, housing conditions and access to rodent feces may also have been factors in disease susceptibility, as kittens came from various sources and were housed in cages adjacent to rodents and rabbits. The two other kittens from the pet store that died suddenly may also have had Tyzzers disease; however, no diagnostics were undertaken on those kittens, so other causes of death cannot be ruled out.

Prevention of death from Tyzzers disease involves maximizing nutritional status, maintaining adequate hygiene of rearing areas, vaccination to prevent predisposing disease conditions, controlling wild rodents, management of parasite burdens, and prompt intensive care of affected individuals.(1,8)

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, multifocal, random, with numerous intracytoplasmic filamentous bacilli.

2. Colon: Colitis, necrotizing, diffuse, moderate, with mild mucosal hyperplasia and numerous intracytoplasmic filamentous bacilli.

Conference Comment:

Necrotizing colitis in kittens is much more common than the occurrence of Tyzzers disease in this species, thus participants also reviewed the more typical etiologies often associated with this lesion. Tritrichomonas foetus causes persistent large-bowel diarrhea in cats less than 1 year of age, with chronic colitis and variably apparent crescent-shaped organisms being the corresponding histologic findings.(2) Although feline panleukopenia virus (FPV, feline parvovirus) more commonly causes small intestinal disease, colonic lesions may also be involved. Feline leukemia virus can cause cryptal necrosis similar to FPV. The small gram-negative bacteria, Anaerobiospirillum is associated with ileocolitis in cats in which it causes crypt abscesses and may lead to septicemia or renal failure.(2)

References:

1. Borchers A, Magdesian KG, Halland S, Pusterla N, Wilson WD. Successful treatment and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmation of Tyzzers disease in a foal and clinical and pathologic characteristics of 6 additional foals (1986-2005). J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:1212-8.

2. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007;114, 227, 278-279.

3. Headley SA, Shirota K, Baba T, Ikeda T, Sukura A. Diagnostic exercise: Tyzzers disease, distemper, and coccidiosis in a pup. Vet Pathol. 2009;46:151-4.

4. Ikegami T, Shirota K, Goto K, Takakura A, Itoh T, Kawamura S, et al. Enterocolitis associated with dual infection by Clostridium piliforme and feline panleukopenia virus in three kittens. Vet Pathol. 1999;36:613-5.

5. Ikegami T, Shirota K, Une Y, Nomura Y, Wada Y, Goto K, et al. Naturally occurring Tyzzers disease in a calf. Vet Pathol. 1999;36:253-5.

6. Iwanaka M, Orita S, Mokuno Y, Akiyama K, Nii A, Yanai T, et al. Tyzzers disease complicated with distemper in a puppy. J Vet Med Sci. 1993;55:337-9.

7. Kovatch RM, Zebarth G. Naturally occurring Tyzzers disease in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1973;163:136-8.

8. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd edition, Blackwell Publishing, Ames, Iowa: 2007;57-8, 138-40, 187-8, 208, 225-6, 271-3.

9. Raymond JT, Topham K, Shirota K, Ikeda T, Garner MM. Tyzzers disease in a neonatal rainbow lorikeet (Trichoglossus haematodus). Vet Pathol. 2001;38:326-7.

10. Simpson VR, Hargreaves J, Birtles RJ, Marsden H, Williams DL. Tyzzers disease in a Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) in Scotland. Vet Rec. 2008;163:539-43.

11. Young JK, Baker DC, Burney DP. Naturally occurring Tyzzers disease in a puppy. Vet Pathol. 1995;32:63-5.

12. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infections. In: Zachary JF, McGavin DM, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2012:174.