Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

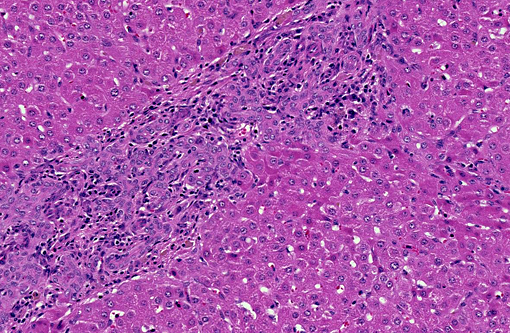

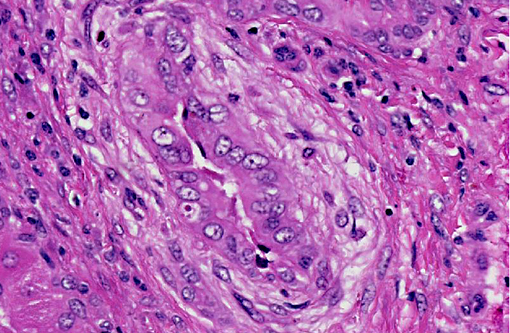

Large and medium-sized intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts are the primary target of the toxin and may become attenuated or completely occluded in severe cases. The changes in these ducts is virtually pathognomonic for sporidesmin toxicity,(3,4,6) the portal fibrosis and biliary ductular hyperplasia representing non-specific secondary changes following blockage of larger ducts.

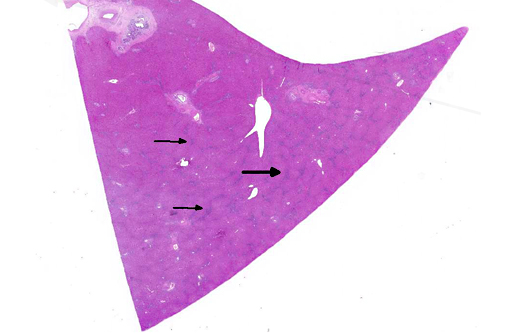

Although lesions occur throughout the liver, the left (ventral) lobe is affected more severely than the right lobe. In chronic cases, especially those where animals are exposed to sublethal doses over more than one year, the left lobe may be markedly atrophic and exist only as a fibrous remnant, sometimes containing small remnants of hyperplastic hepatocytes. In such cases, the right lobe is typically hypertrophic and the liver is rounded in shape.

Subacute sporidesmin toxicity is characterized by a marked increase in the serum activity of GGT (often well above 1000 IU/L), which remains elevated for several months following exposure to the toxin.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Phomopsin is a mycotoxin produced by the saprophytic fungus Phomopsis leptostromiformis, which commonly infects lupines; it is a potent microtubule inhibitor that results in mitotic arrest during metaphase. Thus, in addition to biliary hyperplasia and hepatic fibrosis, this condition is characterized microscopically by the presence of numerous bizarre mitoses. Phomopsin toxicosis is also associated with hepatogenous photosensitivity.(1,5) Toxic pentacyclic triterpenes (especially Lantadene A, B, and C) from the shrub Lantana camara induce hepatic cholestasis, icterus and hepatogenous photosensitization in ruminants, primarily cattle. Lantana hepatotoxicosis is distinguished histologically by megalocytosis, bile accumulation and bile duct proliferation.(5) Saponins of the South African plant Tribulus terrestris (alone or in combination with sporidesmin) are likely responsible for geeldikkop (yellow bighead) in sheep, which is characterized by hepatocyte vacuolation and Kupffer cell hyperplasia in acute toxicosis, and the presence of crystalline material within bile ducts in chronic intoxication.(5)

Aflatoxicosis and pyrrolizidine alkaloid toxicity are less commonly associated with photosensitivity in sheep and are considered less likely causes in this case. Of the numerous types of aflatoxin reported, the most common is aflatoxin B1, which is typically produced by Aspergillus sp. Following metabolism by hepatic cytochrome p450 enzymes, in species that lack adequate glutathione-s-transferase, toxic metabolites cause multiple carcinogenic, toxic and teratogenic effects. In the liver, histological features include hepatocellular necrosis in acute cases, and hepatic fibrosis, hepatocellular megalocytosis and biliary hyperplasia in more chronic cases. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids from Senecio, Crotalaria and Heliotropium sp. are metabolized via hepatic cytochrome p450 enzymes into dehydropyrrolizidine (DHP) derivatives, which cause similar hepatic lesions to those described for aflatoxicosis. Sheep are thought to be relatively resistant to both aflatoxin and pyrrolizidine alkaloid toxicity; cattle, horses, farmed deer, and pigs are most susceptible.(1,5)

Photosensitization is generally classified into three broad categories: types 1, 2 and 3 (see included table). Type 1, or primary photosensitization occurs following ingestion of preformed photodynamic toxins, such as hypericin in St. John's Wort, fagopyrin in buckwheat, and certain drugs, including phenothiazine and tetracycline. Type 2 photosensitization is due to congenital enzyme deficiencies resulting in endogenous pigment accumulation. Bovine congenital hematopoietic porphyria results from deficient levels of uroporphyrinogen III cosynthetase, a key enzyme in heme biosynthesis. Porphyrins subsequently accumulate in dentin and bone, causing the teeth and bone to appear pink and fluoresce upon exposure to ultraviolet radiation. Porphyrins also accumulate in the skin, where they cause necrosis, likely via induction of reactive oxygen species or xanthine oxidase. Affected cattle are anemic, and the accumulated pigments are excreted in the urine, which appears brown. Bovine erythropoietic protoporphyria, on the other hand, is an autosomal recessive condition in Limousin cattle caused by a defect in ferrochelatase, which allows accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in the blood and tissue. This disease is characterized solely by the presence of photodermatitis. There is no anemia, and the teeth, bones and urine are not discolored. Facial eczema, as demonstrated in this case, is associated with type 3, or hepatogenous, photosensitization. This is the most common form. It occurs in conjunction with primary hepatocellular damage (or, less commonly, bile duct obstruction) and is due to impaired hepatic excretion of the potent photodynamic agent, phylloerythrin. Phylloerythrin is a breakdown product of chlorophyll, formed by microbes in the gastrointestinal tract and transported via portal circulation; hepatocytes normally take up phylloerythrin and excrete it into bile. In animals on a chlorophyll-rich diet and generalized hepatic damage, phylloerythrin builds up in various tissues, including the skin. The distribution of the photodermatitis is similar in all types of photosensitization; it is generally confined to sparsely-haired, lightly pigmented, sunlight exposed areas of the skin.(2)

Table: Categories of photosensitization.(2)

| Type | Causes |

| Type 1: Primary | Ingestion of preformed photodynamic toxins in plants and drugs:

|

| Type 2 | Congenital enzyme deficiencies resulting in endogenous pigment accumulation:

|

| Type 3: Hepatogenous | Build-up of phylloerythrin due to generalized hepatocellular damage or bile duct obstruction |

References:

2. Ginn PE, Mansell JE, Rakich PM. Skin and appendages. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007:623-626.

3. Mortimer PH, Stanbridge TA. Changes in biliary secretion following sporidesmin poisoning in sheep. Journal of Comparative Pathology. 1969;79:267-275.

4. Smith BL, Embling PP. Facial eczema in goats: the toxicity of sporidesmin in goats and its pathology. New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 1991;39:18-22.

5. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007:368-381.

6. Thompson KG, Jones DH, Sutherland RJ, Camp BJ, Bowers DE. Sporidesmin toxicity in rabbits: biochemical and morphological changes. Journal of Comparative Pathology. 1983;93:319-329.