Signalment:

Gross Description:

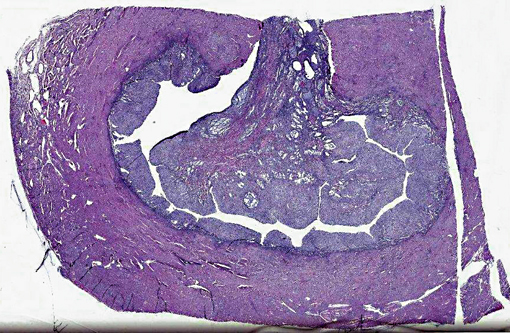

1. Vaginal mass: 4.8 x 3.2 x 2 cm multilobular dark red/black mass.Â

2. Uterus and ovaries: serosa: multiple dark red/black foci.Â

3. Uterus Lumen. 1.9 x 2.8 x 1.9 white, firm polyploid intrauterine mass.Â

4. Omentum: 6.5 x 5.5 x 3 cm round mass with numerous fingerlike projections covered by a smooth surface found in the omentum.Â

5. Omentum: 2 cm smaller mass.

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Intra-uterine mass, endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS), high grade.

2. Omental masses, metastatic ESS.Â

Lab Results:

| Parameter | Normal Range | Feb 2010 | Apr 2010 |

| WBC | 5.5-19.0 x 103/mL | 21.9 | 4.0 |

| Total protein | 7.8-9.6 g/dl | 5.1 | 6.1 |

| BUN | 8-20 mg/dl | 25 | 24 |

| Albumin | 3.1-5.3 g/dl | 3.0 | 3.8 |

| AST | 14-30 U/L | 22 | 40 |

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

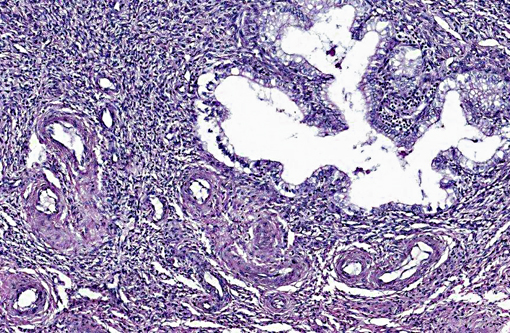

A uterine tumor in a 25-year-old chimpanzee, presented to necropsy for tuberculosis, was comprised of cells similar to proliferating endometrial stroma, and contained medium sized muscular arteries, as well as a fibrillar lattice around the cells.(20) The cells, arranged in cords, clumps and swirls, had lightly basophilic, ovoid to spindle-shaped nuclei with an indistinct nucleolus, and a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm. (20)

In the mouse, ESS is not uncommon. It is found within the wall or protruding into the lumen of the uterus. Murine ESS may arise within benign, endometrial stromal polyps.(13,15) These polyps may contain foci of greater malignancy, characterized by mitosis, cellular atypia, vascular deformation with hematoma or hemorrhage, and necrosis.(13) As in other species, ESS is arranged in sheets with whorls or fascicles of intersecting, spindle-shaped cells with indistinct borders and marked cellular pleomorphism.(15) Giant cells may be seen, though most cells are oval, fusiform cells with scanty basophilic cytoplasm and spherical nuclei with dispersed clumps of chromatin.(13) The neoplastic cells may be surrounded by a fibrillar and collagenous matrix.(3) Metastases may occur in the myometrium, cervix, and other abdominal structures.(15) ESS can be modeled in vivo using mice with mutations in p53 genes, which are treated with mutagens such as N-ethyl-N-nitrosurea (ENU).(9)

ESS has been reported in a 12-year-old, domestic shorthair queen presenting with depression, anorexia, panting, vomiting and a purulent vaginal discharge. A 3 x 10 cm solid mass was palpated in the abdomen, and radiographs demonstrated different sized masses less than 1.5 cm in the lungs.(19) The intra-abdominal mass showed both endometrial stromal and smooth muscle cells with focal tumor cell necrosis. The stromal cells had small, ovoid and spindle-shaped cells with scant cytoplasm, arranged in a diffuse pattern, with prominent vasculature.(19) The cells showed moderate nuclear pleomorphism and no mitotic figures. Neoplastic cells were also seen within blood and lymphatic vessels. Endometrial stromal cells stained positive with Vimentin.(19)

In captive African hedgehogs, Atelerix albiventris, submitted to IDEXX and Zoo/Pathology services for routine pathology, ESS was the second most commonly diagnosed uterine tumor, and was often found during hysterectomies.(16) Vaginal bleeding (13/15 animals), hematuria for two days to six months (11/15), as well as weight loss (5/12), were reported.(16) The ESS tumors were similar to adenosarcomas (the most common tumor), except they did not contain a tubular epithelial component. ESS tumors were dense, polyploid nodules of 1-15 mm in diameter, and often were locally invasive. The stromal cells contained mitotic figures, formed fascicles and whorls, and were supported by fibrovascular stroma.(16)

In summary, ESS are formed from the glandular epithelium or connective tissue stroma.(5) The tumors are tan to grey, and extend by polyploid growth into the endometrial cavity, the myometrium and myometrial vessels.(1,8,12) The cells are small, resembling the proliferative phase of endometrial stroma.(1,5) They often encircle small and medium size muscular arteries.(5) ESS is usually aggressive, with local recurrence and metastases.(10) The current classification system states tumors previously called high-grade ESS are now called poorly differentiated or undifferentiated uterine sarcomas.(1) The undifferentiated tumors invade the myometrium, have severe nuclear pleomorphism, high mitotic activity and/or tumor cell necrosis.(8) Immunohistochemical staining has shown endometrial stromal sarcomas to be positive for CD 10 and uniformly negative for CD 34.(2,8) The tumors lack estrogen and progesterone receptors.(18)

The human literature reports early diagnosis is often a challenge, as no imaging modality is reliable preoperatively, although ultrasound and MRI may be more useful than CT.(1) After preoperative imaging for metastasis, bilateral salpingo-oorphorectomy and total hysterectomy are usually performed.(1,18) Lymphadenectomy is controversial as it may not produce a survival benefit.(1,18) Radiotherapy may decrease local recurrence.(10) Chemotherapy, as well as endocrine therapy options are also used.(10,18) JAZF1/JJAZ1, JAZF1/PHF1 and EPC1/PHF1 are cancer specific fusion genes that are being studied as diagnostic and treatment targets.(1,12) Genetic testing of the tissues is planned at a future date.Â

Survival times vary from months to years, depending on the extent and classification of the tumor. Median recurrence time is usually less than two years.(7,10) In one retrospective study, the median survival time in humans for high grade sarcomas was one year, while the median survival time for lower grades ESS was 11 years.(8) The hedgehogs reported had a mean survival time of 303 days post-surgery.(16)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

A recent study of gene expression signatures in uterine endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) and leiomyosarcoma (LMS) in humans found that genes overexpressed in ESS included SLC7A10, EFNB3, CCND2, ECEL1, ITM2A, NPW, PLAG1 and GCGR; whereas, genes overexpressed in LMS included CDKN2A, FABP3, TAGLN, JPH2, GEM, NAV2 and RAB23.(6) Many genes overexpressed in LMS included those that code for myosin light chain and caldesmon, but not the genes coding for desmin or actin. CD10 was not overexpressed in ESS. Interestingly, although CD10 was once considered specific for ESS, it has been shown to be expressed in many adenosarcomas as well as LMS and 33% of undifferentiated endometrial or uterine sarcoma. Approximately a quarter of all ESS in this study were CD10 negative, thus raising the question of the usefulness of this marker in human uterine sarcomas.(6)

References:

2. Bhargava R, Shia J, Hummer AJ, Thaler HT, Tornos C, Soslow RA. Distinction of endometrial stromal sarcomas from 'hemangiopericytomatous' tumors using a panel of immunohistochemical stains. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:40-47.Â

3. Brayton C. Spontaneous disease in commonly used mouse strains. In: The Mouse in Biomedical Research. 2nd edition. Anonymous 2nd ed. 2007: Ch 25.Â

4. Cline JM, Wood CE, Vidal JD, Tarara RP, Buse E, Weinbauer GF, et al. Selected background findings and interpretation of common lesions in the female reproductive system in macaques. Toxicologic Pathology. 2008;36:142S-163S.Â

5. Cooper TK, Gabrielson KL. Spontaneous lesions in the reproductive tract and mammary gland of female non-human primates. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2007;80:149-170.Â

6. Davidson B, Abeler VM, Hellesylt E, et al. Gene expression signatures differentiate uterine endometrial stromal sarcoma from leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(2):349-55.Â

7. D'Angelo E, Prat J. Uterine sarcomas: a review. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:131-139.Â

8. D'Angelo E, Spagnoli LG, Prat J. Comparative clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of uterine sarcomas diagnosed using the World Health Organization classification system. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1571-1585.

9. Friel AM, Growdon WB, McCann CK, Olawaiye AB, Munro EG, Schorge JO, et al. Mouse models of uterine corpus tumors: clinical significance and utility. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2010;2:882-905.

10. Gadducci A, Cosio S, Romanini A, Genazzani AR. The management of patients with uterine sarcoma: a debated clinical challenge. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:129-142.Â

11. Goodman D. Neoplastic and nonneoplastic lesions in aging F344 rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1979;48:237-248.Â

12. Kurihara S, Oda Y, Ohishi Y, Iwasa A, Takahira T, Kaneki E, et al. Endometrial stromal sarcomas and related high-grade sarcomas: immunohistochemical and molecular genetic study of 31 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1228-1238.Â

13. Maekawa A, Maita, K. Changes in the ovary. In: Uea M, ed. Pathobiology of the Aging Mouse. 1996.Â

14. Maita K, Hirano M, Harada T, Mitsumori K, Yoshida A, Takahashi K, et al. Spontaneous tumors in F344/DuCrj rats from 12 control groups of chronic and oncogenicity studies. J Toxicol Sci. 1987;12:111-126.Â

15. Maronpot RR, Boorman GA, Gaul BW. Pathology of the Mouse, Reference and Atlas. 1st ed. Vienna, IL: Cache River Press;1999.Â

16. Mikaelian I, Reavill DR, Practice A. Spontaneous proliferative lesions and tumors of the uterus of captive African hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2004;35:216-220.Â

17. Nagaoka T. Spontaneous uterine adenocarcinomas in aged rats and their relation to endocrine imbalance. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1990;116:623.

18. Reich O, Regauer S. Hormonal therapy of endometrial stromal sarcoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:347-352.

19. Sato T, Maeda H, Suzuki A, Shibuya H, Sakata A, Shirai W. Endometrial stromal sarcoma with smooth muscle and glandular differentiation of the feline uterus. Vet Pathol. 2007;44:379-382.

20. Toft JD. Endometrial stromal tumor in a chimpanzee. Vet Pathol. 1975;12:32-36.Â