Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 1, Case 4

Signalment:

9-year-old, gelding, warmblood, horse, Equus caballus.

History:

This horse presented with a 1-year history of a bleeding rostral nasal mass.

Gross Pathology:

N/A

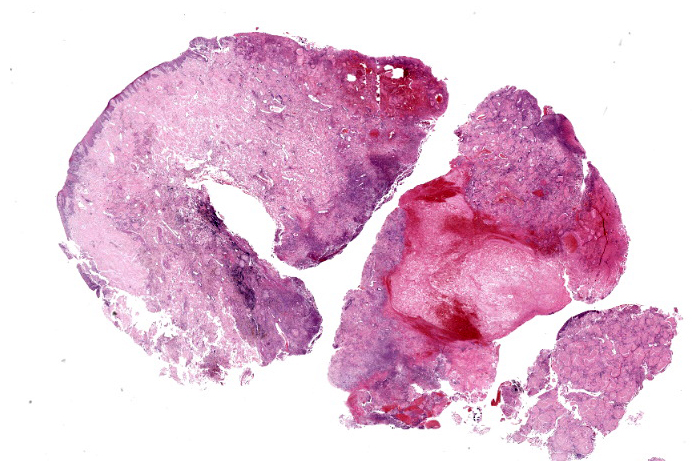

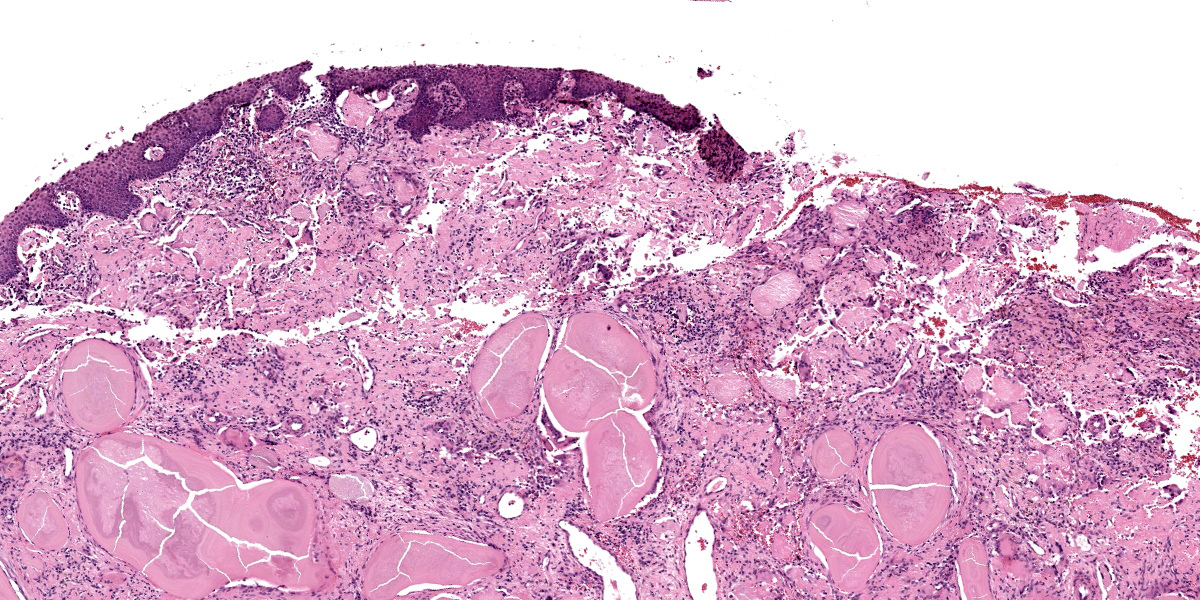

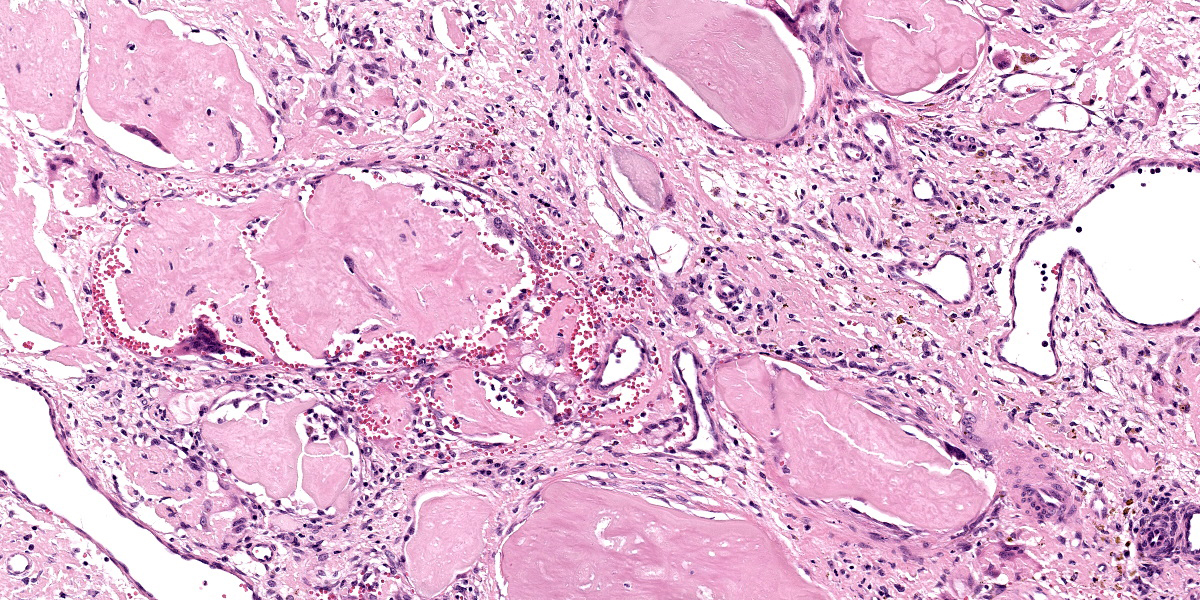

Microscopic Description:

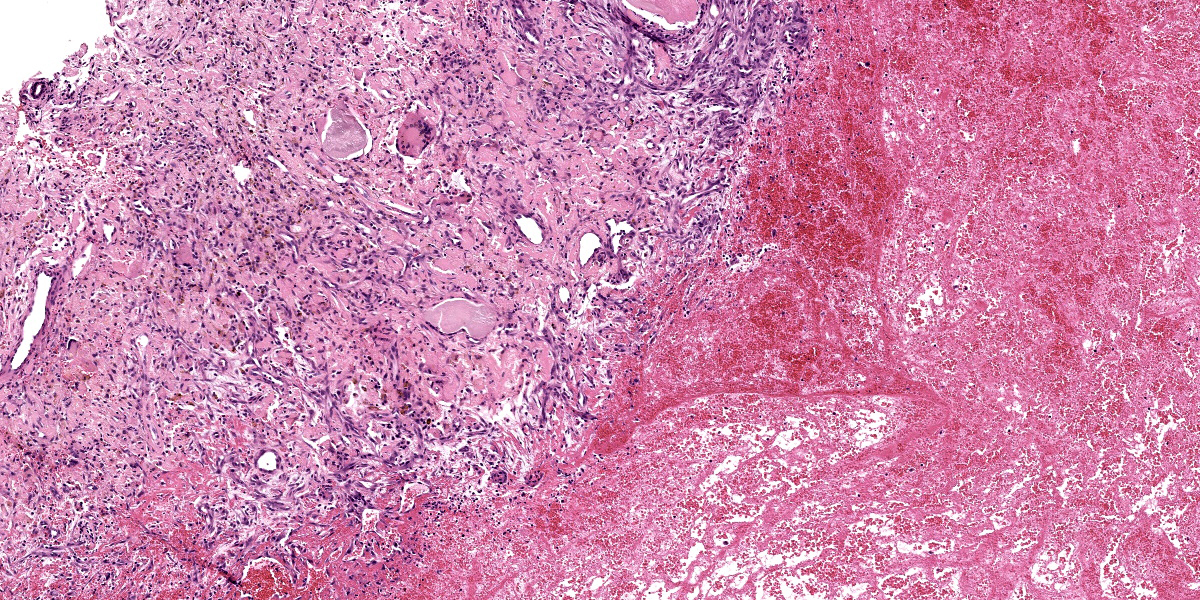

Slide A: Examined are three sections of the nasal vestibule lined by a multifocally eroded stratified squamous epithelium that has numerous individualized neutrophils percolating throughout (neutrophilic exocytosis). The vestibular lamina propria is markedly expanded by numerous, large, multinodular deposits of pale eosinophilic, amorphous, smudgy, extracellular material (amyloid). Associated with this amyloid deposition are thick anastomosing bands of fibrous connective tissue that are punctuated by plump reactive fibroblasts and branching small-caliber vessels lined by plump endothelium (granulation tissue). Numerous neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and multinucleated giant cells percolate throughout this granulation tissue and are interspersed between amyloid deposits. The vestibular lamina propria is additionally expanded by large pools of brightly eosinophilic amorphous to fibrillar material (necrosis) admixed with numerous extravasated red blood cells (hemorrhage), degenerate leukocytes, and hemosiderin and hematoidin-laden macrophages.

Slide B: Congo red: The pale eosinophilic, amorphous extracellular material stains orange-red (congophilic) and exhibits apple-green birefringence under polarized light.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Nasal vestibule: Severe, chronic, locally extensive amyloidosis with neutrophilic and histiocytic nasal vestibulitis, granulation tissue, epithelial erosion, multifocal necrosis, and chronic-active hemorrhage.

Contributor’s Comment:

Equine nasal amyloidosis is an uncommon manifestation of local amyloidosis. Its most common presentation is a single or multiple, often ulcerated, mass-like lesions in the rostral nasal cavity or nasal vestibule; however, amyloidosis can occur in any portion of the nasal cavity and can present as diffuse swelling and not a discrete mass.1,5-8,12 Concurrent cutaneous, conjunctival, and/or corneal amyloidosis has also been documented.5,12 Clinical signs often include epistaxis and larger masses may lead to respiratory difficulty and exercise intolerance.1,5-8 Grossly, the masses caused by amyloidosis can be soft to firm, are often ulcerated, and can have a smooth to waxy appearance.5-8 Histologic findings are similar amongst all described cases with the presence of eosinophilic, amorphous material, often associated with granulation tissue, hemorrhage, lymphoplasmacytic histiocytic inflammation, multinucleated giant cells, and occasionally mineralization. The histopathologic findings in this case were similar to those in previous reports.

Amyloid is an extracellular, hyalinized, proteinaceous material composed of polypeptides arranged in beta-pleated sheets forming fibrillar proteins.4 Due to the conformation of amyloid, it is resistant to degradation leading to accumulation within tissues. Thirty different types of types of amyloid fibril proteins have been discovered, but only nine have been studied in domestic animals and only two, amyloid light chain (AL) and amyloid A (AA), have been described in horses.1,2,9 Equine nasal amyloidosis is caused by accumulation of the amyloid light chain (AL) type.1

Diagnosis of amyloid is commonly achieved through histochemical staining of with Congo Red, which results in orange to red coloration that exhibits apple-green birefringence when observed under polarizing light.4 Additionally, amyloid light chain (AL) and amyloid A (AA) can be differentiated using a pre-treatment with potassium permanganate. Amyloid A (AA), when pre-treated with potassium permanganate will lose its affinity for Congo red and subsequently lacks the typical birefringent properties.10

Differentials on gross examination include fungal granuloma, ethmoid hematoma, habronemiasis, sarcoids/soft tissue sarcomas, and maxillary dental tumors that extend into the nasal cavity; however, all of these differentials can be differentiated histologically by the absence of amyloid.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences, Section of Anatomic Pathology, Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, Ithaca, New York

JPC Diagnosis:

Nasal muscosa: Amyloidosis, multifocal, severe, with fibrin thrombi, chronic hemmorrhage, and ulceration.

JPC Comment:

Conference 1 concludes with a relatively straightforward case. The thick squamous epithelial layer that lacks underlying hair follicles helps to place the tissue as the nostril (specifically within the nasal vestibule). The contributor provides a nice description of the features of this case and reviews the salient points of equine amyloidosis as well. The diagnosis of amyloidosis was readily confirmed as the eosinophilic extracellular material was strongly congophilic and sharply birefringent under polarized light. There was discussion among conference participants about the degree of hemorrhage and fibrin present in this case. The major takeaway was that these changes were the direct result of amyloid being deposited within the walls of blood vessels and not just in the lamina propria as is more readily apparent.

This case is an example of immunoglobulin-derived (AL) amyloidosis which is rare in animals though relatively common in humans.11 Other reported causes of primary amyloidosis include immune dyscrasias such as extramedullary plasmacytomas and multiple myeloma where overproduction of immunoglobulin light chains (or fragments) by plasma cells coalesce to form insoluble fibrils.1,11 One case of systemic AL amyloidosis secondary to multiple myeloma in a horse has been described to date.3 In contrast, secondary (reactive; AA) amyloidosis is more common in veterinary species and familial forms of AA amyloidosis have also been described. Reactive amyloidosis occurs secondary to chronic inflammatory stimulus and production of serum amyloid A protein, or less commonly, due to nonimmunocyte dyscrasia or idiopathic causes.11 Renal and/or hepatic involvement with deposition of extracellular amyloid A protein disrupts normal function and eventually may cause organ failure; others tissues may similarly be affected.11 This is seen in both domestic animals as well as captive wildlife species such as flamingos and cheetahs among many others. Familial forms of AA amyloidosis occur in Shar Pei dogs and Abyssinian cats, though other breeds have also been identified.11

Amyloidosis has been a frequent feature in slide conferences over the years, though horses are not as well represented as the dog in this regard. Ocular amyloid secondary to recurrent uveitis (‘moon blindness’) was covered in Conference 7, Case 3, 2018-2019 and represents AA amyloid. Cutaneous amyloidosis in the horse represents a localized AL amyloidosis that is distinct from the nasal form.

References:

- Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:483.

- Johnson KH, Westermark P, Sletten K, O'brien TD. Amyloid proteins and amyloidosis in domestic animals. Amyloid. 1996 Jan 1; 3(4):270-89.

- Kim DY, Taylor HW, Eades SC, Cho DY. Systemic AL amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma in a horse. Vet Pathol. 2005 Jan;42(1):81-4.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Diseases of the Immune System. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2021:259-264.

- Mould JR, Munroe GA, Eckersall PD, Conner JG, McNeil PE. Conjunctival and nasal amyloidosis in a horse. Equine Veterinary Journal. 1990 Sep;22(S10):8-11.

- Nappert G, Vrins A, Doré M, Morin M, Beauregard M. Nasal amyloidosis in two quarter horses. The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 1988 Oct;29(10):834.

- Portela R, Dantas A, Melo D, Marinho J, Neto P, Riet-Correa F. Nasal Amyloidosis in a Horse. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Pathology. 2012; 5: 86-88.

- Shaw DP, Gunson DE, Evans LH. Nasal amyloidosis in four horses. Veterinary Pathology. 1987 Mar;24(2):183-5.

- Sipe JD, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, et al. Amyloid fibril protein nomenclature: 2012 recommendations from the Nomenclature Committee of the International Society of Amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2012;19(4):167-70.

- Van Rijswijk MH, van Heusden CW. The potassium permanganate method. A reliable method for differentiating amyloid AA from other forms of amyloid in routine laboratory practice. Am J Pathol. 1979;97(1):43-58.

- Woldemeskel M. A concise review of amyloidosis in animals. Vet Med Int. 2012;2012:427296.

- Østevik L, Gunnes G, de Souza GA, Wien TN, Sørby R. Nasal and ocular amyloidosis in a 15-year-old horse. Acta Vet Scand. 2014 Aug 27;56(1): 50.