Signalment:

11-year-old Saddlebred gelding, horse,

Equus caballus.This horse was referred to Purdue University Veterinary Teaching Hospital after being rescued from a barn fire. The horse had been treated with intranasal oxygen by firefighters, with dexamethasone and furosemide by the attending veterinarian. Of four other horses in the barn, two died and two remained stable.

On admission, the horse had marked respiratory distress (manifested by nostril flaring, increased abdominal efforts, and cyanotic mucous membranes) and evidence of pulmonary edema (frothy nasal discharge and bilateral crackles on thoracic auscultation). It also had tachycardia with hypovolemia and marked hypoxemia. Despite supportive treatment, the horses condition did not improve, so it was humanely euthanized.

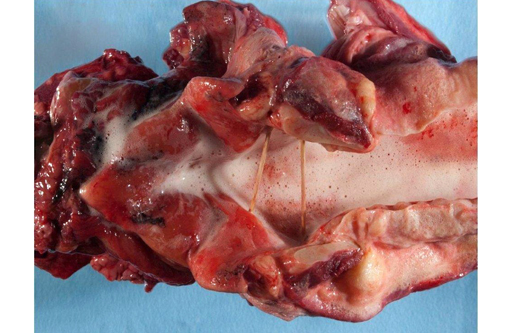

Gross Description:

The nasal and pharyngeal mucosa was diffusely thickened, dark red to green, wet, and glistening with streaks or mats of black granular material. The larynx was diffusely thickened by edema with streaks or specks of black granular material on the mucosal surface. The tracheal lumen was filled with clear frothy fluid; tracheal submucosa was diffusely expanded with transparent yellow edema fluid. The lungs were heavy, wet, and non-collapsing. On cut section, abundant clear colorless to red frothy fluid flowed from the airways and pulmonary parenchyma. Aggregates of black fibrillar to granular specks were in the pulmonary parenchyma and tracheobronchial lymph nodes. The pericardium contained approximately 50 ml of serosanguineous fluid.

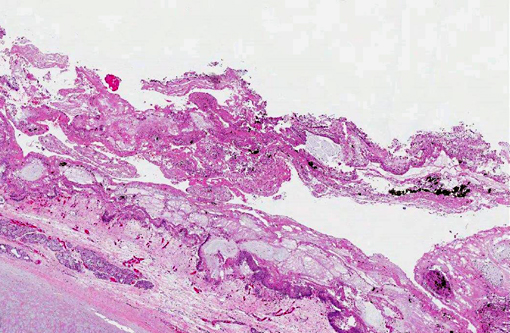

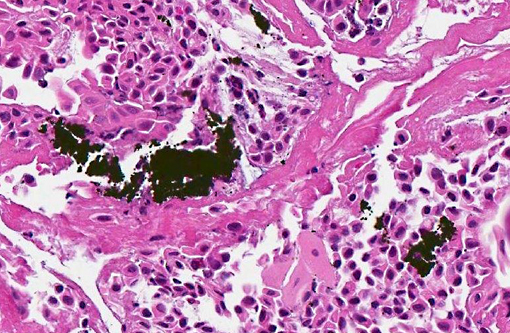

Histopathologic Description:

Pharyngeal and laryngeal mucosa is eroded or ulcerated with fibrinosuppurative exudate, free erythrocytes and carbon particle accumulation. The propria-submucosa is expanded by poorly stained edema fluid and variably sized aggregates of neutrophils. Blood vessels are distended with blood. Lymphatic vessels and some glands and ducts contain numerous neutrophils and macrophages. The remaining epithelial lining has a few necrotic ciliated epithelial cells with pyknosis and hypereosinophilic cytoplasm. In the lung (not included in the submitted slide), bronchi and bronchioles were partially or totally obstructed by thick, amphophilic mucus mixed with black carbon particles, numerous leukocytes, including neutrophils, mast cells, and eosinophils, and sloughed epithelial cells. The associated bronchial/bronchiolar epithelium was multifocally attenuated or sloughed. The interlobular septa were diffusely expanded by poorly stained edema fluid.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Necrotizing pharyngitis and laryngitis with intralesional carbon particles.

Condition:

Smoke inhalation

Contributor Comment:

Inhalation of smoke and associated gases in a closed space can cause severe acute respiratory injury, which is a major cause of death in fires.(2,4,5,6) The severe acute respiratory injury that occurs in barn fires can be explained through three pathophysiological mechanisms; direct thermal injury, carbon monoxide intoxication, and chemical irritation.(4,6) Thermal injury causes local edema, necrosis, inflammation and upper airway obstruction by direct insult to the microvasculature and coagulation of tissue.(6) Carbon monoxide, which is produced by incomplete combustion, leads to delayed or interrupted oxygen delivery due to low blood oxygen content, which can lead to pulmonary vasoconstriction and hypoxia.(4,6) The severity of the chemical insult depends on the burned products, which may include hydrogen cyanide, hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, or aldehydes. These compounds initially induce mucosal hyperemia, but as long as the carbon particles containing the chemical remain on the mucosal surface, they can cause severe inflammation and mechanical pressure resulting in peribronchial edema or mucosal sloughing and necrosis. The damage to respiratory mucosal epithelium also results in decreased mucociliary transport and clearance of bacteria or foreign material in the airways.(4,6)

JPC Diagnosis:

Pharyngeal and laryngeal mucosa: Necrosis, multifocal to coalescing, with marked edema and numerous aggregates of carbon particles.

Conference Comment:

Conference participants found tissue identification somewhat difficult, as much of the respiratory epithelium has been effaced by necrosis. Discussion centered on classification and morphology of direct thermal injury. Direct thermal burns are classified into the following categories based on the depth of their involvement: superficial burns are restricted to the epidermis; partial thickness burns involve the dermis; and in full thickness burns there is damage to subcutaneous tissue or underlying muscle tissue. Grossly, partial-thickness burns are pink, blistered, and painful; whereas full thickness burns are white, charred, and non-painful due to the destruction of nerve endings in the tissue. As seen in this case, thermal burns are characterized histologically by coagulative necrosis that is often sharply demarcated from vital tissue.(3)

Conference participants also discussed the phases of injury associated with smoke inhalation, noting that during the early phase (first 24 hours) of smoke inhalation, there is acute pulmonary insuffiency due to bronchoconstriction and upper airway damage. This is followed within the next 24 to 72 hours by the middle phase, characterized by the development of pulmonary edema and laryngeal reflux. The pulmonary edema obstructs nasal passages and can lead to pneumonia. During the late phase, bronchopneumonia develops and worsens due to several factors, including the loss of protective barriers such as mucociliary clearance and surfactant as well as the blockage of effective inflammatory response owing to compromised blood flow in the area.(3)

References:

1. Hanson RR. Management of burn injuries in the horse.

Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2005;21:105-123.

2. Kirkland KD, Goetz TE, Foreman JH, Francisco C, Baker GJ. Smoke inhalation injury in a pony.

J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 1993; 3:83-89.

3. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. Environmental and nutritional diseases. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, eds.

Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010: 421-422.

4. Marsh PS. Fire and smoke inhalation injury in horses.

Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2007;23:19-30.

5. McFarlane D. Smoke inhalation injury in the horse.

J Equine Vet Sci. 1995;15(4):159-162.

6. Norman TE, Chaffin MK, Johnson MC, et al. Intravascular hemolysis associated with severe cutaneous burn injuries in five horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;226(12):2039-2043.