Conference 14, Case 4

Signalment:

6 year-old female Merino sheep (Ovis aries)

History:

Six of 2,300 5-6 year old first cross ewes run on improved pastures in the Cowra district of NSW were noticed to be unusually thin in late October 2014. As ovine Johne’s disease was considered a possibility, one of these ewes was euthanased and necropsied on the 26 November 2014.

Gross Pathology:

The serosa of the small intestine, caecum and colon was covered in miliary to focally extensive firm, white, raised plaques. In some areas, the plaques were as small as 1mm diameter, pinpoint lesions, whereas in others as much as 90 percent of the serosal surface was covered.

Laboratory Results:

N/A.

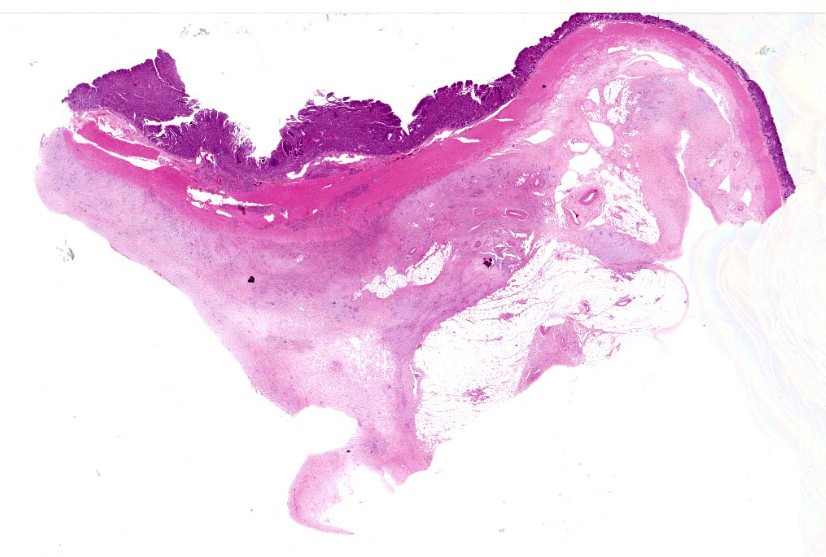

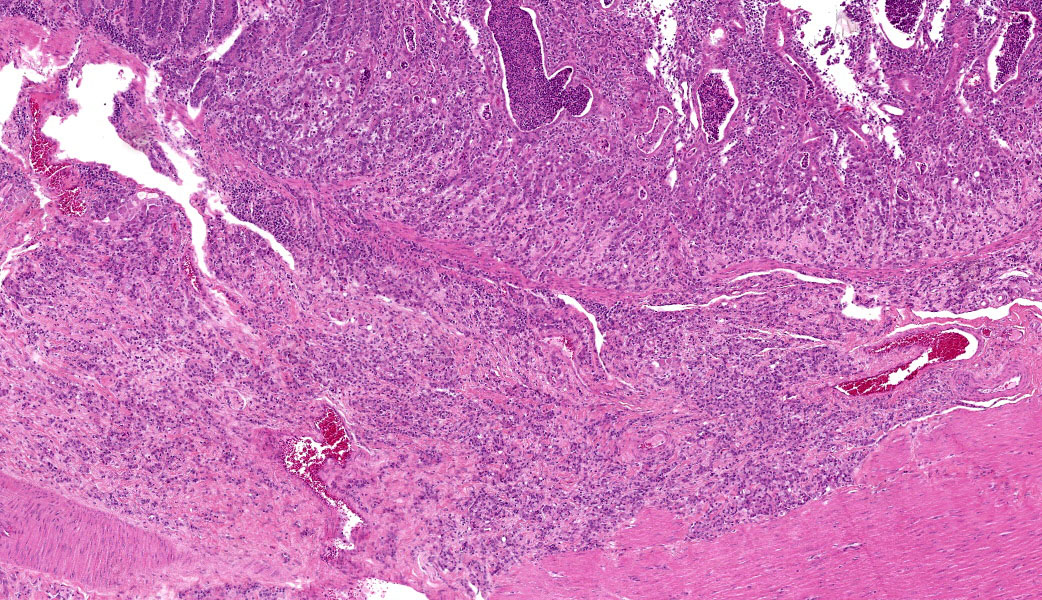

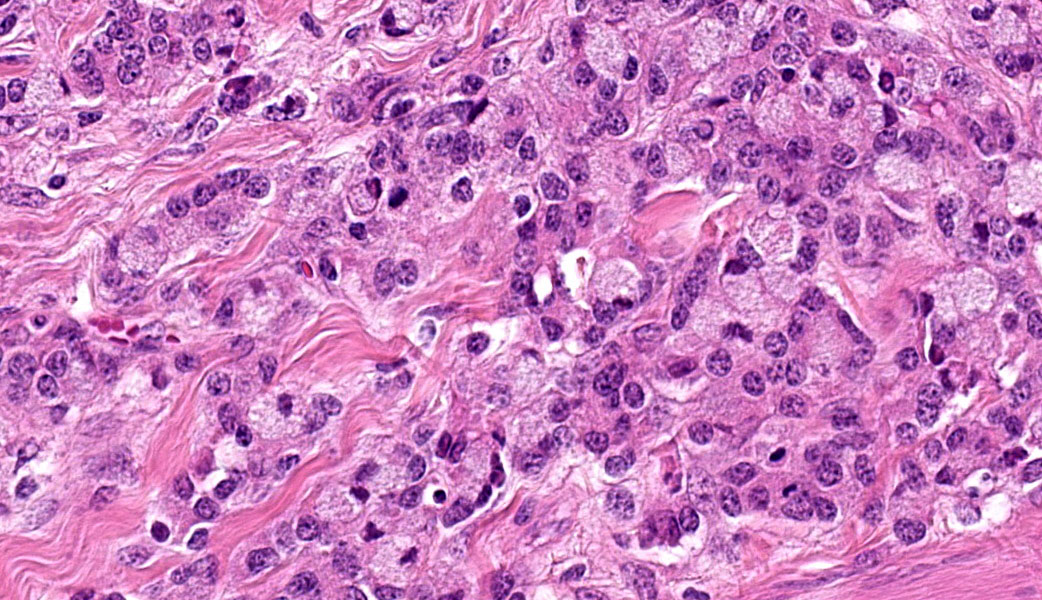

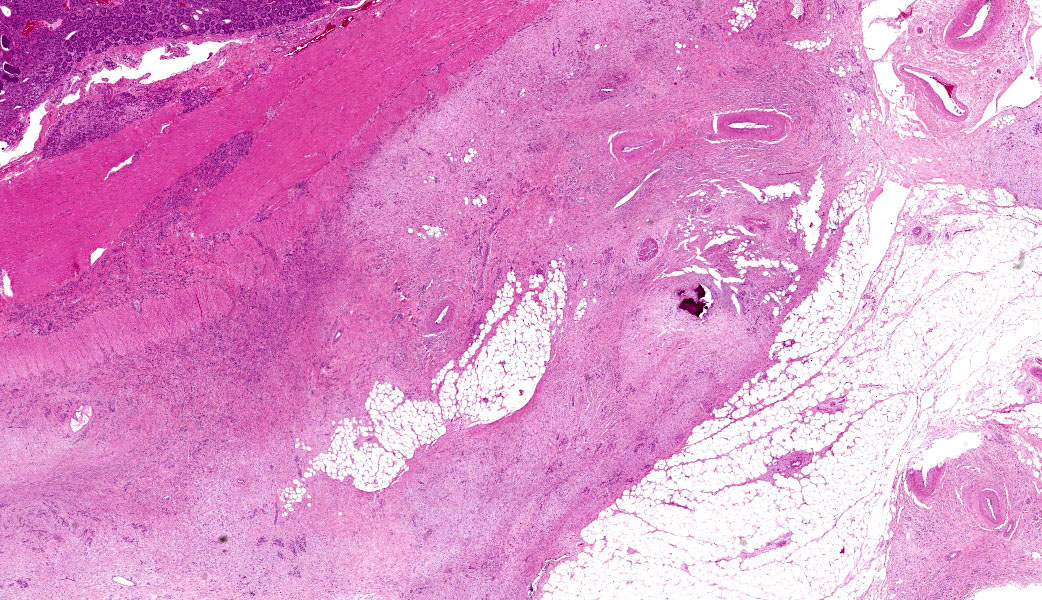

Microscopic Description:

Colon: The lamina propria, submucosa, muscularis mucosa and serosa are markedly expanded by a poorly demarcated, non-encapsulated, infiltrative neoplasm composed of two populations of neoplastic epithelial cells. The neoplastic cells occur singly and in loose packets, lobules and cords, and are supported by variable fibrous stroma containing fibrocytes, fibroblasts and a light basophilic matrix. The predominant neoplastic cell is round to ovoid, 20–50 μm in diameter, with distinct cell borders, abundant finely granular basophilic cytoplasm, peripherally located oval nuclei with lightly stippled pale chromatin and single nucleoli. The secondary type of neoplastic cell is round to oval; 15-30 μm in diameter; with distinct cell borders; moderate amounts of cytoplasm containing small eosinophilic granules; single, peripherally located, large nuclei with coarse chromatin and single nucleoli. Both sub-populations of neoplastic cells exhibit moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. Mitoses are rare (< 1 per HPF). There is moderate expansion of the adventitia of large vessels with neoplastic cells. The lamina propria propria is diffusely expanded by moderate numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, occasional macrophages and rare eosinophils. Crypts are often ectatic, lined with attenuated epithelium and containing non-degenerate neutrophils, rare macrophages and lymphocytes (crypt abscess).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Large intestine, colon: Intestinal adenocarcinoma, sheep (Ovis aries), ruminant.

- Large intestine: Colitis, lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, diffuse, mild, with multifocal crypt abscesses.

Contributor’s Comment:

Intestinal adenocarcinoma is a common gastrointestinal tumour of older sheep.4,11 A wide range of neoplasms have been described in sheep, adenocarcinoma of the small intestine is reported to be the most common of these by far (Table 1).2 Most are usually discovered at slaughter as incidental findings; if clinical signs are present, weight loss and occasionally ascites are usually the only signs. In an early report of the disease, Ross (1980) reported an overall prevalence of 0.272 percent in sheep examined at abattoirs in southern NSW, and McDonald and Leaver (1965) found that 0.4 percent of all sheep on a single property and 2 percent of sheep over 5 years of age had lesions consistent with intestinal adenocarcinoma.5,12

To date, only a limited number of studies have investigated factors associated with intestinal adenocarcinoma in sheep. According to Simpson (1972), intestinal adenocarcinoma in New Zealand is more common in British breeds than in “fine wool” breeds, and is associated with increased stocking density.13 Ross (1980) reported that regional prevalence in NSW varied between 0.2 to 1.5 percent, however Simpson (1972) found that geographic variation in the prevalence of intestinal adenocarcinoma was not statistically significant.12,13 Munday et al. (2009) found no association between intestinal adenocarcinoma and herpesviruses, Helicobacter spp., or Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis in sheep in New Zealand.9

Intestinal adenocarcinomas have been reported in a wide range of animal species. 3 Ovine intestinal adenocarcinomas appear histologically similar to human colonic adenocarcinomas, although there are differences in site of primary growth, development of polyps, and site of metastasis.6 Neoplastic ovine intestinal adenocarcinoma cells grown in vitro do not express fibronectin, and have altered expression of beta-catenin, E-cadherin, cycloxygenase-2, and p53 protein.7,10 Mismatch repair protein defects do not appear to be associated with tumorigenesis.8 Other differential diagnoses for chronic ill-thrift in sheep include ovine Johne’s disease (OJD), malnutrition, balanoposthitis, cutaneous myiasis, peritonitis and pneumonia. 11 From a production and biosecurity perspective, OJD is of the most concern. The two diseases appear markedly different grossly and histologically, although the simultaneous occurrence of both diseases has been reported by Bush et al. (2006).1

Table 1: Neoplasms in sheep described at the Ruakura Animal Health Laboratory from 1955 to 1968. Adapted from Cordes and Shortridge (1971)2

|

Site of neoplasm |

No. of cases |

Diagnosis |

|

Small intestine |

143 |

Mucous-gland adenocarcinoma |

|

Liver |

12 |

Hepatoma |

|

2 |

Adenocarcinoma - possibly primary in genitalia |

|

|

Liver and/or pancreas |

15 |

Ductal adenocarcinoma |

|

Adrenal |

1 |

Cortical adenoma |

|

Pituitary |

1 |

Adenocarcinoma of pars intermedia |

|

Ovary |

3 |

Granulosa tumour |

|

Testicle |

2 |

Seminoma |

|

1 |

Sertoli cell tumour |

|

|

Kidney |

1 |

Renal adenocarcinoma |

|

3 |

Embryonal nephroma |

|

|

Epidermis |

4 |

Papilloma of skin |

|

2 |

Squamous carcinoma of mouth |

|

|

1 |

Metastatic squamous carcinoma in liver and colon |

|

|

1 |

Squamous carcinoma of ear |

|

|

Reticuloendothelial system |

32 |

Lymphosarcoma - lymphoid |

|

7 |

Lymphosarcoma - reticulum cell |

|

|

of |

1 |

Thymoma |

|

Blood vessel |

8 |

Angiosarcoma of: |

|

brain (1) |

||

|

liver (5) |

||

|

stifle joint (1) |

||

|

hock joint (1) |

||

|

Nerve |

1 |

Neurofibroma of wall of thorax |

|

Striated muscle |

3 |

Rhabdomyoma of heart |

|

Brain |

1 |

Astrocytoma |

|

Other connective tissues |

4 |

Fibrosarcoma |

|

3 |

Myxosarcoma |

|

|

2 |

Osteogenic sarcoma |

|

|

1 |

Liposarcoma |

|

|

1 |

Synovioma |

Contributing Institution:

State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

Elizabeth Macarthur Agricultural Institute

Woodbridge Rd

Menangle

NSW 2568

Australia

JPC Diagnoses:

Ileocecal junction: Intestinal adenocarcinoma.

JPC Comment:

This last case is a classic! Many thanks to the contributor for a great submission and write-up. Most participants were readily able to reach a diagnosis of intestinal adenocarcinoma in this case due to the high mitotic rate, degree of invasion the neoplasm into abluminal tissue layers, and the striking desmoplastic response. The deep infiltration from the mucosa outwards allows for a strong argument of a primary intestinal adenocarcinoma rather than a metastatic carcinoma. Intestinal adenocarcinomas tend to invade from the mucosa deep into and run laterally through the submucosa and subsequent layers.

In sheep, the primary ruleout would be metastatic uterine adenocarcinoma, but this would more likely present on the serosal surface due to direct seeding of the abdomen (carcinomatosis) or via lymphatic spread rather than invading from the mucosa. Additionally, intestines are not a primary site for lymphatic metastases for uterine adenocarcinoma in most species; the lungs, liver, and mesentery, however, are.3 Although generally considered an incidental finding at slaughter, previous studies have demonstrated an increased incidence of intestinal adenocarcinoma in sheep in New Zealand following exposure to feedstuffs sprayed with phenoxy and picolinic acid herbicides.10

Despite being able to reach a diagnosis, most participants struggled with the specific anatomic location for this tissue. After much back and forth, the consensus amongst conference-goers was that this is likely representative of the ileocecal junction or close to it, since there are features of both small and large intestine on opposite ends of the H&E slide. While there are crypts, mucus glands, and subcutaneous fat consistent with large intestine visible on one side, there are also villi on the other, most clearly seen associated with and around the neoplasm.

Lastly, there are notable mucosal erosions with regional neoplasia-associated architecture disruption that most participants felt was likely the cause of the inflammation present in the slide rather than an additional primary enteritis. As such, this is reflected in the JPC morphologic diagnosis, which focuses solely on the neoplasm and considers the other changes to be secondary.

References:

- Bush RD, Toribio JA, Windsor PA: The impact of malnutrition and other causes of losses of adult sheep in 12 flocks during drought. Aust Vet J. 2006:84(7):254-260.

- Cordes D, Shortridge E: Neoplasms of sheep: a survey of 256 cases recorded at Ruakura Animal Health Laboratory. NZ Vet J. 1971:19(4):55-64.

- Hananeh WM, Ismail ZB, Daradka MH. Tumors of the reproductive tract of sheep and goats: A review of the current literature and a report of vaginal fibroma in an Awassi ewe. Vet World. 2019;12(6):778-782.

- Lingeman CH, Garner F: Comparative study of intestinal adenocarcinomas of animals and man. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1972:48(2):325-346.

- Maxie G: Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals: 3-Volume Set: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2007.

- McDonald JW, Leaver DD: Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine of Merino sheep. Australian Veterinary Journal. 1965:41(9):269-271.

- Munday JS, Brennan MM, Jaber AM, Kiupel M: Ovine intestinal adenocarcinomas: histologic and phenotypic comparison with human colon cancer. Comp Med. 2006:56(2):136-141.

- Munday JS, Brennan MM, Kiupel M: Altered expression of beta-catenin, E-cadherin, cycloxygenase-2, and p53 protein by ovine intestinal adenocarcinoma cells. Vet Pathol. 2006:43(5):613-621.

- Munday JS, Frizelle FA, Whitehead MR: Mismatch repair protein expression in ovine intestinal adenocarcinomas. Vet Pathol. 2008:45(1):3-6.

- Munday JS, Keenan JI, Beaugie CR, Sugiarto H: Ovine small intestinal adenocarcinomas are not associated with infection by herpesviruses, Helicobacter species or Mycobacterium avium subspecies J Comp Pathol. 2009:140(2-3):177-181.

- Newell KW, Ross AD, Renner RM. Phenoxy and picolinic acid herbicides and small-intestinal adenocarcinoma in sheep. Lancet. 1984;2(8415):1301-5.

- Norval M, Head K, Else R, Hart H, Neill W: Growth in culture of adenocarcinoma cells from the small intestine of sheep. British journal of experimental pathology. 1981:62(3):

- Radostits OM, Gay CC, Hinchcliff KW, Constable PD: Diseases caused by bacteria Veterinary Medicine: A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats, and Horses: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:920.

- Ross AD: Small intestinal carcinoma in sheep. Aust Vet J. 1980:56(1):25-33.

- Simpson BH: The geographic distribution of carcinomas of the small intestine in New Zealand sheep. New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 1972:20(3):24-28.