WSC 22-23

Conference 23

Case 1:

Signalment:

16-years old, female spayed, French bulldog, Canis lupus familiaris, canine

History:

The dog was presented to the animal hospital for mass of the right eye that had grown from two months ago. Marked exophthalmos was observed in the right eye and enucleation was performed.

Gross Pathology:

Most of formalin fixed material was neoplastic tissue and normal ocular structures were unclear. On cut surface, there was scattered bleeding and necrosis in the tumor tissue.

Laboratory Results:

Microscopic Description:

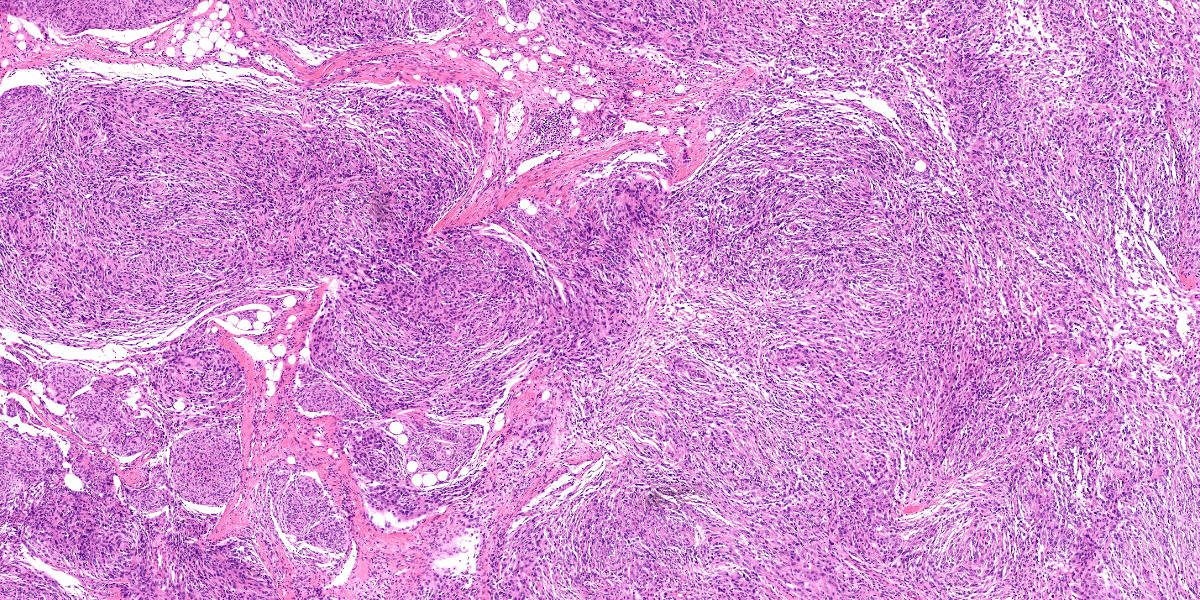

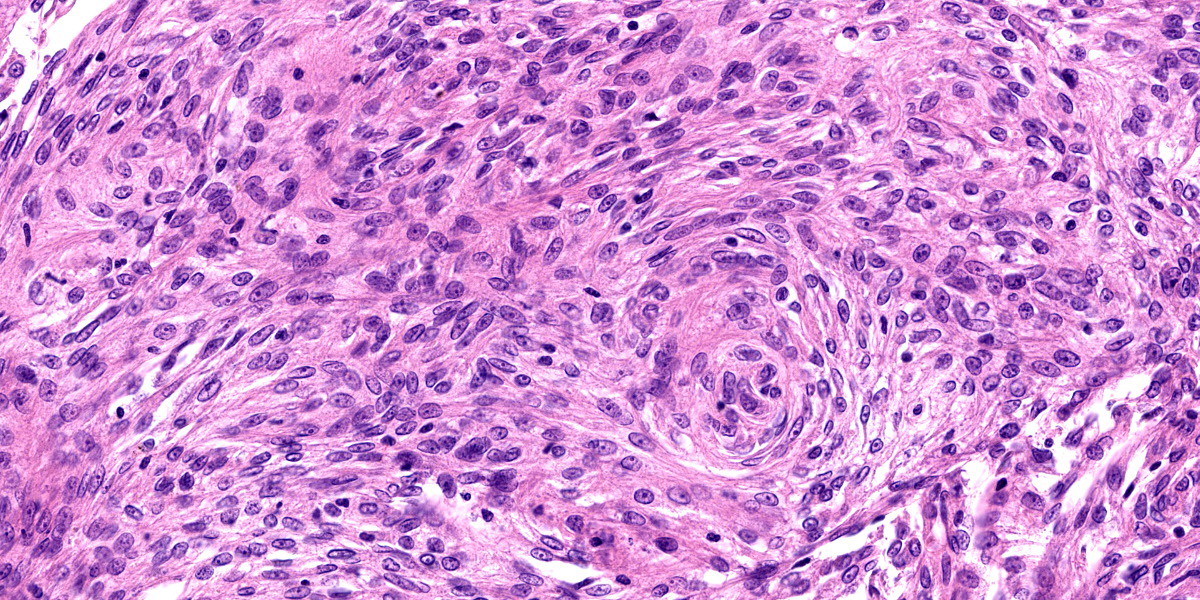

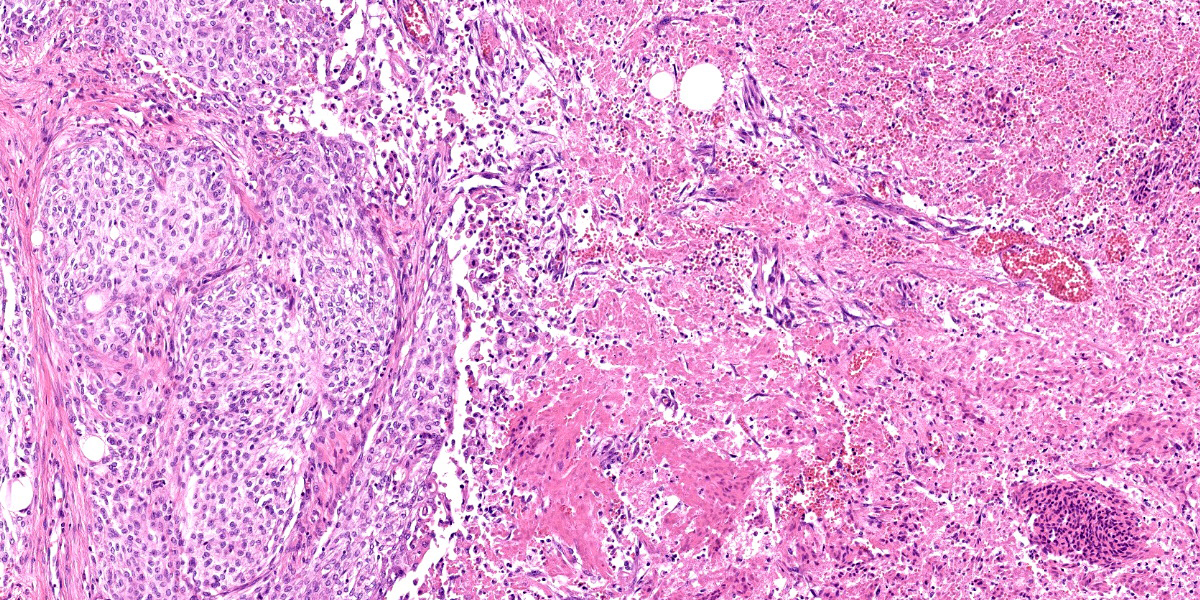

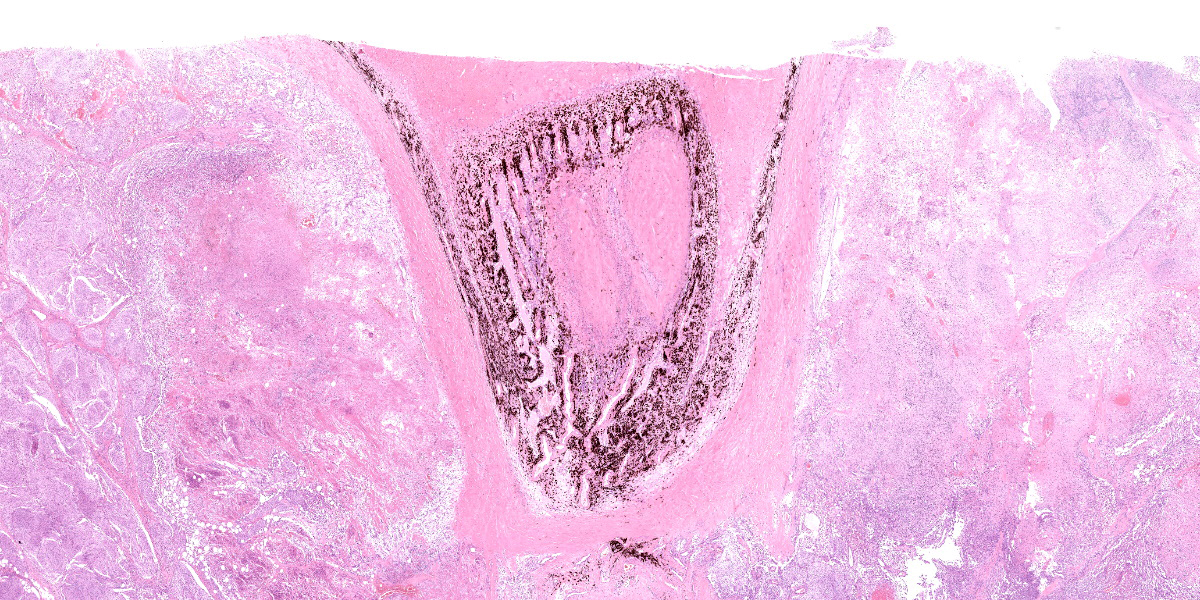

The nonencapsulated and poorly demarcated mass surrounded the optic nerve behind the globe. The mass consisted of spindle or epithelioid polygonal cell arranged in whorls, bundles or sheets, and often formed tumor islands of variable size and lobules separated by fibrovascular stroma. These tumor cells had various amounts of pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with slightly distinct cell margins. The cells had ovoid nuclei with stippled chromatin and occasional clear nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anysokaryosis was mild. 11 mitotic figures were observed under 10 high-magnification fields of view. Several large to small foci of necrosis and hemorrhage were also seen. Although no tumor invasion was observed into the eye tissue, the neoplastic cells extensively invaded into peripheral adipose and muscle tissues. Clusters of neoplastic cells were seen in some lymphatic or blood vessels. The ocular structures markedly compressed by the tumor. In other specimens submitted, the corneal epithelium showed hyperplastic thickening with some small pustules and ulcer. In the substantia propria of cornea, severe fibrosis with mild hemorrhage, edema and infiltration of lymphocytes can be seen. The structures of the iris and ciliary body were collapsed, the lens and retinae were obscure.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Eye: Orbital meningioma, right eye, dog

Contributor’s Comment:

Meningioma is a common primary brain tumor in dogs (up to 45%) and cats (60%), and most intracranial meningiomas occur as well?demarcated solitary masses. However, meningioma in the retrobulbar site accounts for only 2 to 3 % of all meningiomas and develops surrounding optic nerve area with invasion into peripheral tissue.14,15 Meningioma is derived from arachnoidal cap lining arachnoid villi. In veterinary medicine, orbital meningioma is considered a primary lesion originating in meninge covering intraorbital or intracanalicular optic nerve, while in human medicine, some are observed as secondary lesion occurring intracranially and extend along the optic nerve.6,7

Orbital meningioma is characterized by proliferation in sheets or cluster of various sized epithelioid cells with glassy eosinophilic cytoplasm and may form whorls or bundles as is the intracranial cases, but psammoma bodies are rare. While chondro-osseous metaplasia is rare in intracranial meningioma, it is frequently observed in orbital meningiomas and is useful for diagnosis.13,14,18 In 3 previous cases in the Wednesday Slide Conference, epithelioid or spindle cells arranged in small lobules and whorls in 2 cases (Conference 19, 2013, Case 2; Conference 20, 2015; Case 4) , epithelioid cells arranged in nests and sheets predominated in 1 case (Conference 7, 2018, Case 4), and chondro-osseous metaplasia was seen in all cases. This case is thought to be typical orbital meningioma at the point of location and histological morphology except for the lack of chondro-osseous metaplasia.

Although immunohistochemistry is not always necessary in typical cases, it may be useful for excluding other differential diagnosis such as carcinoma. In general, neoplastic cells show positive reaction for vimentin, S100 and neuron specific enolase in varying degree, and negative for pancytokeratin and glial fibrillary acidic protein, however, cytokeratin expression was detected in few cases on a report .2,11,13,15

Orbital meningioma is slow growing and malignant variants are rarely reported. One study of 22 canine orbital meningiomas revealed that 6 of 17 recurred and furthermore 2 of them presented subsequent central blindness suggesting intracranial invasion of the tumor.10 In addition, two other reports showed distant metastasis to lung.12,16 These aggressive biologic behaviors of this tumor might be associated with stage and progression at the time of excision.

Malignancy of human orbital meningiomas are assessed by WHO grading system for intracranial meningioma, which depends on histologic subtypes and specific cytological features.6,7 In canine intracranial meningioma, application of the system has been proposed because they are likely to exhibit biological similarities to their human counterparts, but it is not yet used for orbital lesions. The number of cases of canine orbital meningioma is small and correlation be

tween grading and prognosis with both types of meningioma has not been validated, therefore the standardization of grading system in canine meningioma needs further studies using larger caseloads.1,11

This case might have poor clinical outcome such as recurring and/or extension into cranium because of the histopathological features including prominent local invasion, lymphovascular invasion and frequent mitotic figures. It was suggested that loss of the eye structure was due to compression by the neoplastic tissue and secondary inflammatory change.

Contributing Institution:

Laboratory of Pathology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Setsunan University,

45-1 Nagaotohge-cho, Hirakata, Osaka 573-0101, Japan

JPC Diagnosis:

Globe, right: Orbital meningioma.

JPC Comment:

Meningioma was last seen in the Wednesday Slide Conference in 2021-2022, conference 7, case 2: this case was an intracranial neoplasm in a cat, and the contributor and conference comments delineate the pathologic and historical aspects of this common neoplasm.

Non-orbital canine meningiomas are classified according to the 2007 WHO human grading system. The two most common types of meningioma, the meningotheliomatous (epithelioid) and transitional (mixed) types, are both considered grade I, as are fibrous, psammomatous, angiomatous, microcystic, and myxoid types.3 Grade II meningiomas include choroid and atypical meningiomas, which have a higher mitotic rate (> 4 per 10 high power fields) and hypercellularity.3 Grade III meningiomas include papillary, rhabdoid, and anaplastic forms, which have cytologic features of malignancy and greater than 20 mitotic figures per 10 high power fields.3,17 While orbital meningiomas are not graded, this week’s moderator, Dr. Jey Koehler from Auburn University, described several concerning features which could potentially be indicative of a more aggressive behavior (and would be characteristic of malignancy in a non-orbital meningioma): large areas of necrosis and regions with significant anisokaryosis and high mitotic rate.

A recent study described four cases of the uncommon rhabdoid meningioma in dogs.17 In all cases, the neoplasms were located in the olfactory or frontal lobes and were locally invasive.17 Rhabdoid cells comprised >70% of the tumor population, were arranged in sheets, and had well-delineated cell borders, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, and hyaline to fibrilliar inclusions which peripheralized the nucleus.17 On electron microscopy, these inclusions were composed of whirling intermediate filaments (consistent with a rhabdoid morphology), a network of extensive cell process interdigitations (consistent with a rhabdoid-like morphology), or abundant mitochondria (consistent with an oncocytic meningioma).

In humans, expression of Ki-67, a marker of proliferation, and osteopontin, a cytokine with multiple activities important in tumor progression, are highly correlated to the histologic grade and recurrence rate of meningiomas.8 Janssen et al recently evaluated 35 canine meningiomas and found that neither Ki-67 nor osteopontin were correlated with histologic grading according to the WHO classification system for human meningiomas.8

Meningiomas have a characteristic cytologic appearance, and samples may be obtained via impression smears or crush preparations of biopsy or by fine needle aspirate.4,5 As on histology, samples from meningiomas may demonstrate whirling or acini formation and psammoma bodies on cytology. Additionally, neoplastic cells may have intracytoplasmic nuclear invaginations or an elongate nucleus with a longitudinal, dark blue linear bar imparting a “coffee bean” appearance to the nucleus.4,5 These characteristic nuclei can be seen on histology throughout the neoplasm in this case as well.

Another primary neoplasm of the optic nerve described in dogs is an ocular astrocytoma.9 This may arise in the optic nerve or within the retina and can lead to retinal detachment.9

References:

- Avallone G, Rasotto R, et al. Review of Histological Grading Systems in Veterinary Medicine. Vet Pathol. 2021;58(5):809-828.

- Barnhart KF, Wojcieszyn J, et al. Immunohistochemical staining patterns of canine meningiomas and correlation with published immunophenotypes. Vet Pathol. 2002;39(3):311-21.

- Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie, MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, Vol I. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2016:396-398, 494.

- DeLorenzi D, Mandara MT. The Central Nervous System. In: Raskin RE, Meyer DJ, eds. Canine and Feline Cytology. 3rd St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2016: 396-400.

- Gould A, Naskou MC, Brinker E. What is your diagnosis? Impression smear from a dog with an intracranial mass. Vet Clin Pathol. 2022; 00:1-5.

- Grossnilaus HE, Eberhart CG, Kivelä TT. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Eye. 139.

- Jain D, Ebrahimi KB, et al. Intraorbital meningiomas: a pathologic review using current World Health Organization criteria. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(5):766-70.

- Janssen J, Oevermann A, Walter I, Tichy A, Kummer S, Gradner G. Osteopontin and Ki-67 expression in World Health Organization graded canine meningioma.

- Labelle P. The Eye. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: 2022. 1423.

- Mauldin EA, Deehr AJ, et al. Canine orbital meningiomas: a review of 22 cases. Vet Ophthalmol. 2000;3(1):11-16.

- Montoliu P, Añor S, et al. Histological and immunohistochemical study of 30 cases of canine meningioma. J Comp Pathol. 2006;135(4):200-7.

- Pérez V, Vidal E, et al. Orbital meningioma with a granular cell component in a dog, with extracranial metastasis. J Comp Pathol. 2005;133(2-3):212-7.

- Regan DP, Kent M, et al. Clinicopathologic findings in a dog with a retrobulbar meningioma. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011; 23(4):857-62.

- Richard RD. Tumors of the Eye. In: Meuten DJ, ed., Tumors in Domestic 5th ed. Ames, IA. Wiley Blackwell. 915-916.

- Robert JH, Andrew WB, et al.: Tumors of the Nervous System. In: Meuten DJ, ed., Tumors in Domestic 5th ed. Ames, IA. Wiley Blackwell. 864.

- Schulman FY, Ribas JL, et al. Intracranial meningioma with pulmonary metastasis in three dogs. Vet Pathol. 1992;29(3):196-202.

- Tabaran AF, Armien AG, Pluhar GE, O’Sullivan MG. Meningioma with rhabdoid features: Pathologic findings in dogs. Vet Pathol. 2022; 59(5): 759-762.

- Wilcock BP: Special Senses. In: Jubb Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 3. St. Louis, US: Elsevier; 2016:487-488.