Signalment:

Nine-year-old, female, golden retriever, (

Canis familiaris).The dog was

brought to the clinic with a history of intermittent rectal prolapse. Clinical

examination revealed a rectal mass (5 cm cranial from the anus), and the dog

was referred to the surgical excision of the mass.

Gross Description:

Rectal

mass: an oval 3x5 cm mass, on cross section light brown in color and firm

consistency.

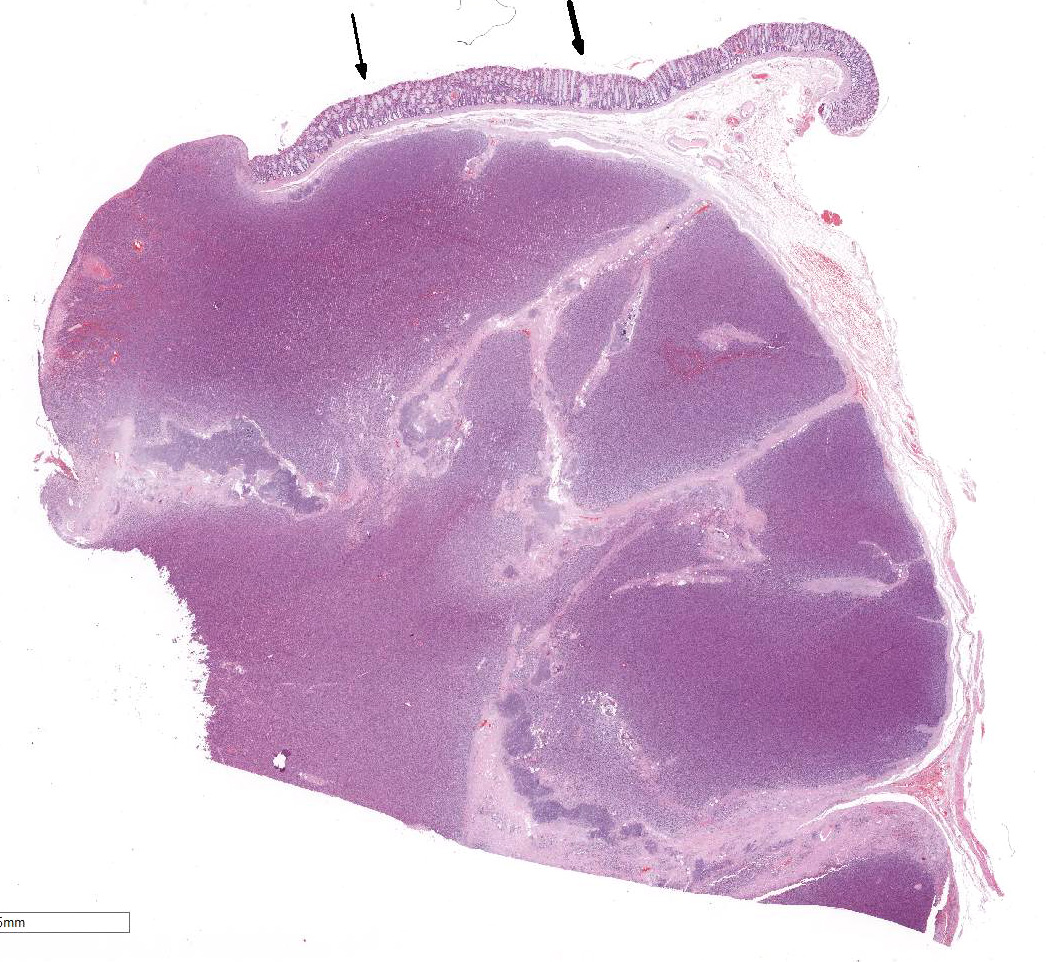

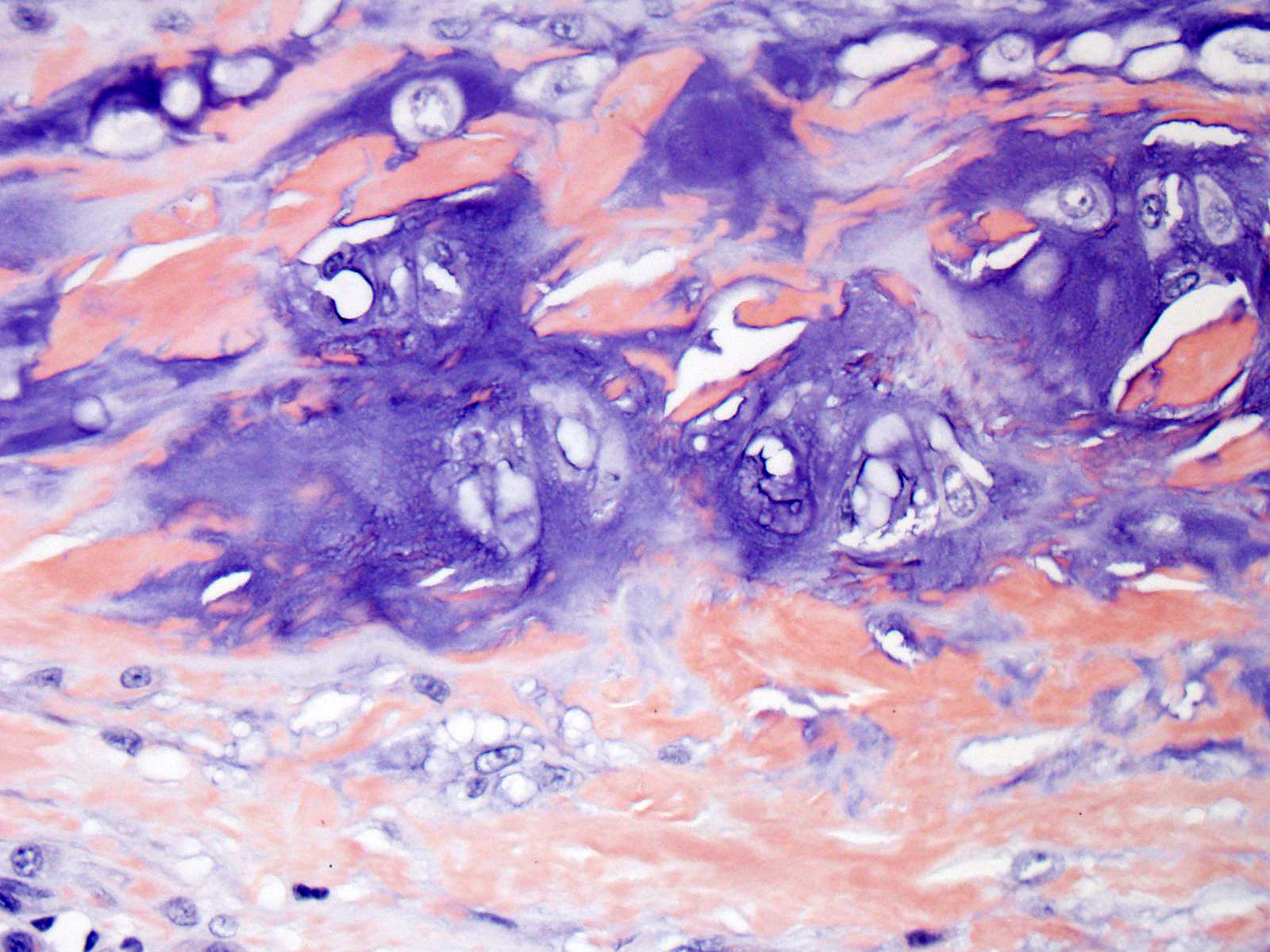

Histopathologic Description:

Rectum:

Expanding the submucosa and elevating the overlying ulcerated mucosa is a

well circumscribed, partially encapsulated, densely cellular neoplasm composed

of sheets and packets of round cells

separated by a fine fibrous stroma.

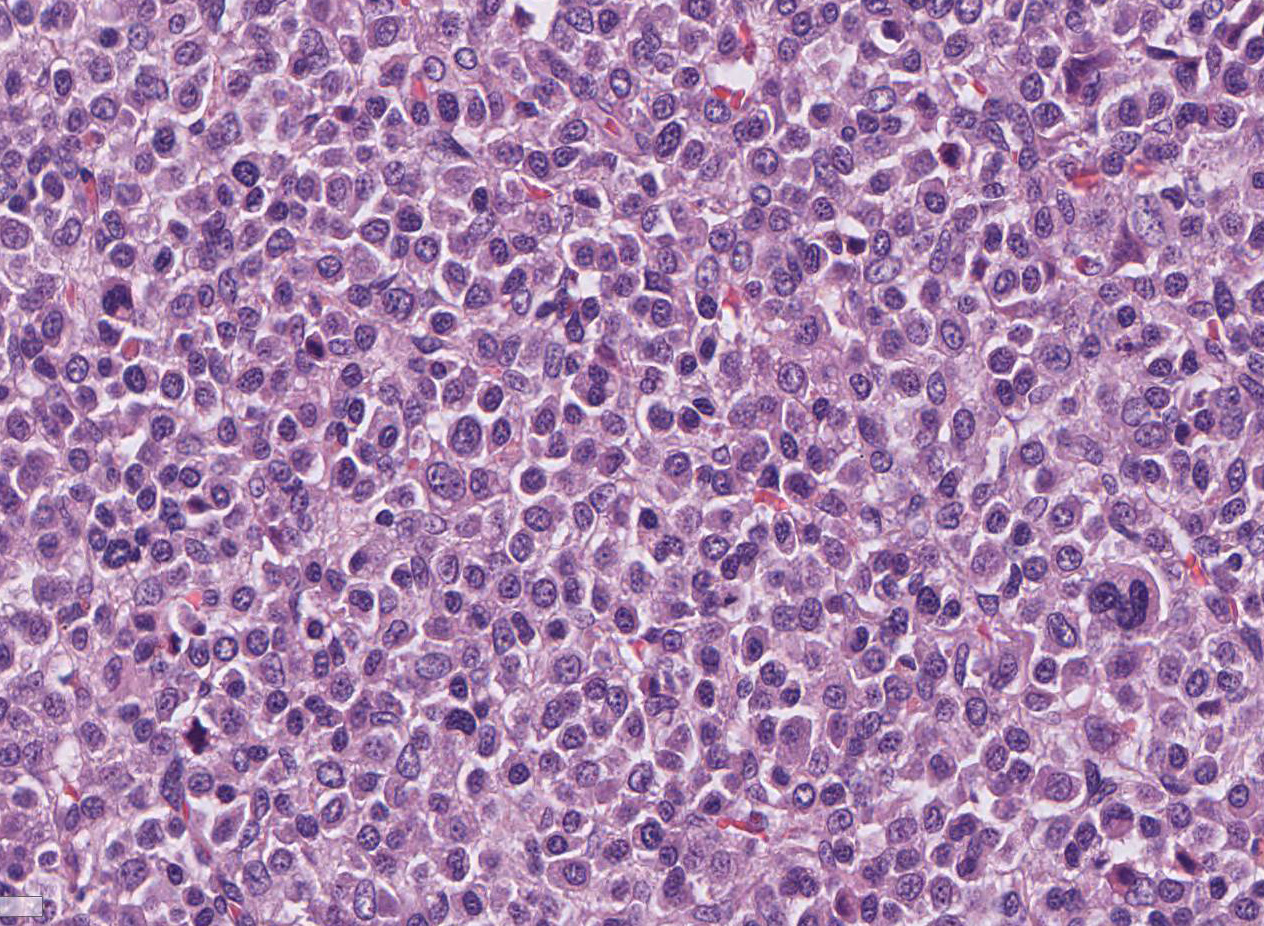

Neoplastic cells have variably distinct cell borders and moderate amounts of

eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. Nuclei are round, rarely oval, usually

eccentrically located with finely stippled to finely clumped chromatin and

usually one indistinct nucleolus. There is moderate anisokaryosis, multifocal

karyo-megaly and a moderate number of multinucleate cells. Mitotic figures

average 10 per 10 HPF. Multifocally between neoplastic cells or at the

periphery of the tumor are variably sized and shaped, extracellular deposits of

amorphous, homogenous, eosinophilic material (amyloid) with multifocal islands

of cartilage formation (cartilaginous metaplasia) that is occasionally

mineralized.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

>Rectum:

Plasmacytoma (or Extramedullary Plasmacytoma), golden retriever, canine.

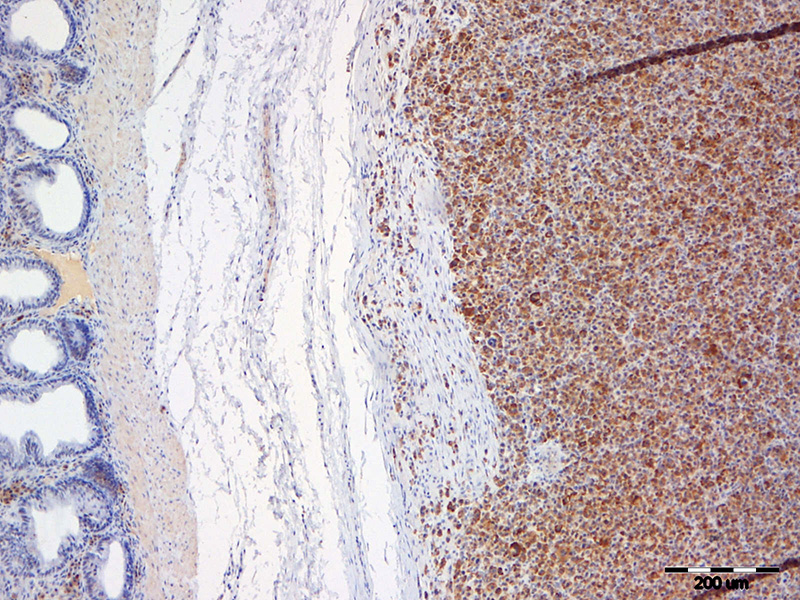

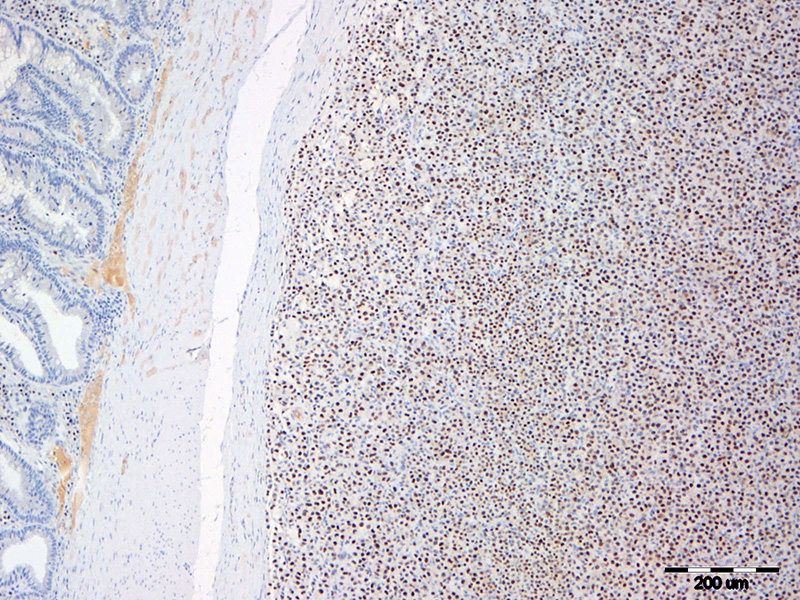

Lab Results:

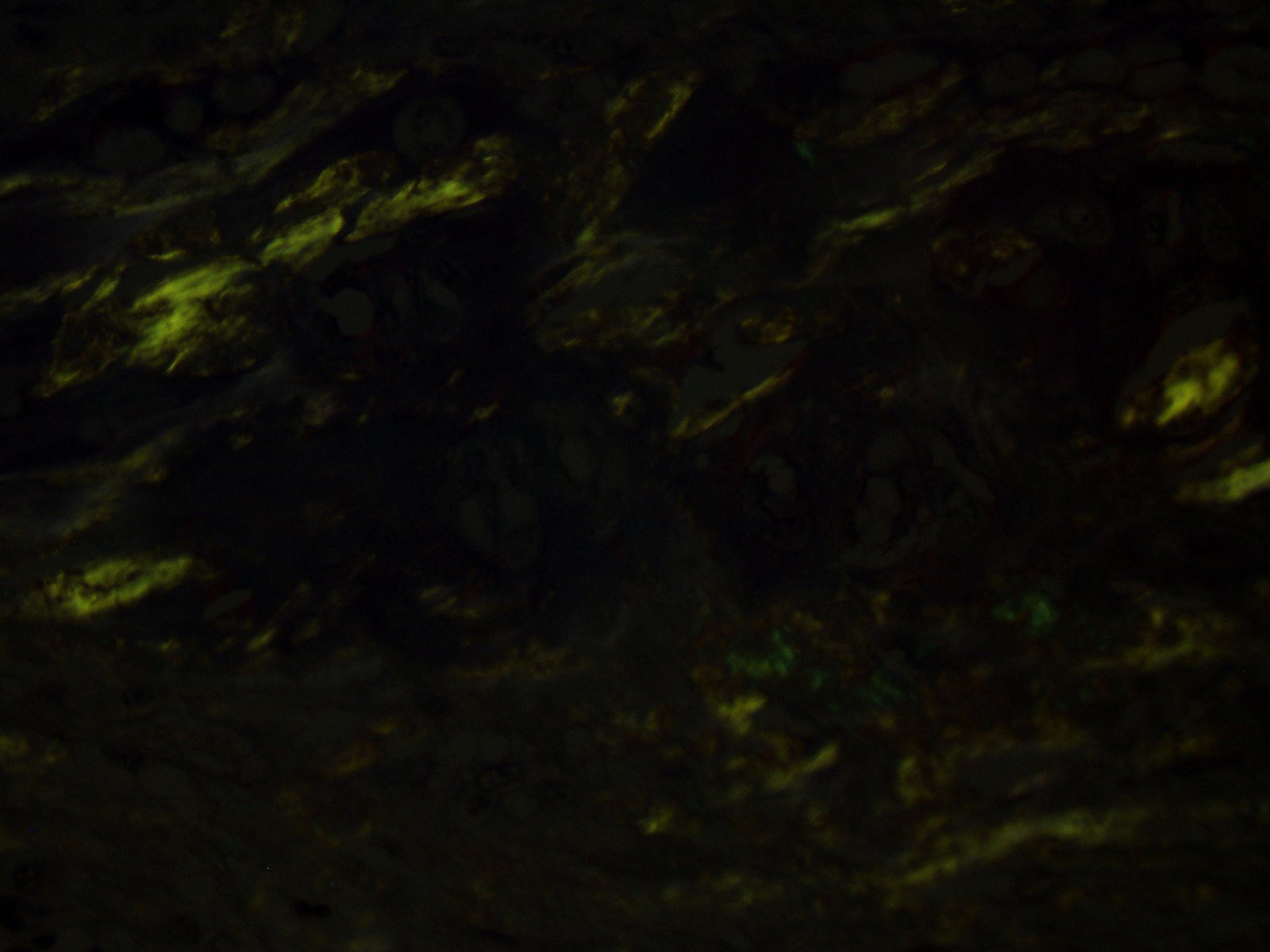

Immunohisto-chemistry antibodies

against CD 3, CD79 and MUM1 were applied. The tumor was CD79 and MUM1 positive,

and CD3 negative. Congo red stain revealed amyloid deposits at the periphery of

the tumor.

Condition:

Extramedullary plasmacytoma

Contributor Comment:

Extramedullary

plasmacytoma (EMP) is a relatively common tumor in older dogs and occur most

frequently on the skin and mucous membranes, but has been reported in other

areas such as the brainstem, spinal cord, lymph nodes, abdominal viscera,

genitalia, and eyes.

2,9

Plasmacytomas of

the lower gastrointestinal tract are uncommon neoplasms in dogs, and rare in

cats and other species. They are encountered most frequently in the submucosa

of the distal colon and rectum of dogs, where they are associated with signs of

large bowel diarrhea and bleeding

5. Gastrointestinal EMP has also

been reported in other sites, including the esophagus, stomach and small

intestine.

10

Histologically

they resemble plasmacytomas of the skin, oral cavity or larynx. The tumor is

formed by solid packets of pleomorphic round cells with various degrees of

plasmacytoid maturation, especially at the periphery of the tumor. There is a

frequent nuclear hyperchromasia and convolution. The cells are typically

arranged in solid endocrine-like packets and there may be AL amyloid deposition

among the tumor cells. The majority of the tumor growth is submucosal. A small

proportion exhibit more aggressive behavior, including invasion of tunica

muscularis, and some spread to regional lymph nodes and spleen.

9

Canine EMP histological typing system has been established and is helpful

diagnostic tool, although the types cannot be used for a tumor grading system.

4

An unusual

finding in plasmacytomas is the presence of cartilage and bone in close

association with amyloid deposits. Meta-plastic bone and cartilage have been

described in two canine intestinal EMPs

5 and in human amyloidosis of

tongue

11 and myelomas.

1 The exact pathogenesis of

chondroid metaplasia in amyloidosis is not clearly described. Ramos Vara and

colleagues hypothesized that in amyloidosis the inducing stimulus for bone

formation is the amyloid deposits, with resultant stimulation of mesenchymal

precursor cells to

differentiate into cartilage- and bone-forming cells under the influence of

soluble factors liberated by histiocytic and other cells.

5

JPC Diagnosis:

Colon: Plasmacytoma, extramedullary, golden retriever,

Canis

familiaris.

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides a great example of a relatively common

neoplasm in the skin or mucus membrane of dogs in an uncommon location within

the abdominal viscera. Extra-medullary plasmacytomas of the lower

gastrointestinal tract have been reported in dogs to occur most frequently in

the submucosa of the distal colon and rectum, as in this case, and are

considered a benign neoplastic proliferation of monoclonal B cells.

9

Rectal and colonic plasmacytomas represent only 4% of all extramedullary

plasmacytomas in dogs.

6 Despite the uncommon location, conference

participants identified solid packets of pleomorphic plasmacytoid round cells

with a perinuclear clearing (Golgi complex) admixed with abundant homogenous

smudgy material recognized as amyloid, commonly deposited in plasma cell

tumors. The contributor confirmed the presence of amyloid via Congo-red

staining and apple-green birefringence with polarized light. The conference

moderator also pointed out the distinctive clumping pattern of the hetero-chromatin,

giving the neoplastic cells the classic clock face histomorphology of plasma

cells.

9

The most striking feature of

this case is the prominent streaks of amyloid within and surrounding the neoplasm,

often admixed with foci of chondroid metaplasia. Amyloid is a proteinaceous

substance composed of polypeptides arranged in beta-pleated sheets and is

deposited in tissues in response to a number of pathogenic processes. Primary

systemic or immunoglobulin associated amyloid (AL) is associated with light

chains derived from plasma cells in monoclonal B cell proliferations of

extramedullary plasmacytomas or multiple myelomas. The light chains are then

converted to amyloid fibrils by proteolytic enzymes in macro-phages and

deposited within tissues.

8 As mentioned by the contributor,

chondroid metaplasia has been uncommonly reported to occur with amyloidosis

secondary to a variety of conditions, although the exact pathogenesis is

currently unknown.

3,11

Another type of amyloid is

formed secondary to a variety of chronic inflammatory conditions inciting

excessive release of serum amyloid associated (AA) acute phase protein,

predominantly by the liver under the influence of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and

IL-1. AA is then deposited in multiple organs including the spleen, pancreas,

intestinal lamina propria, lymph nodes, kidneys and liver.

7,8,9

Amyloid-beta (AB) has been found in cerebral plaques of aging humans and rhesus

macaques and is associated with Alzheimers disease. Interestingly,

neurofibrillary tangles, another feature of Alzheimers disease in humans, have

not been found in aging rhesus macaques.

7

References:

1. Karasick

DV, Schweitzer ME, Miettinen M, OHara BJ. Osseous metaplasia associated

with amyloid-producing plasmacytoma of bone: A report of two cases.

Skeletal Radiol. 1996; 25:263267.

2. Jacobs JM, Messick JB, Valli VE.

Lymphoid Tumors. In: Meuten DJ, ed.

Tumors in Domestic Animals. 4

th

ed. Iowa State Press; Blackwell Publishing; 2002: 163.

3. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ,

Affolter VK.

Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 2nd ed. Ames, IA:

Blackwell; 2005: 870-871.

4. Platz SJ, Breuer W, Pfleghaar S,

Minkus G, Hermanns W. Prognostic value of histopathological grading in

canine extramedullary plasma-cytomas.

Vet Pathol. 1999; 36: 23-27.

5. Ramos-Vara JA, Miller MA, Pace LW,

Linke RP, Common RS, Watson GL. Intestinal multinodular AL deposition

associated with extramedullary plasmacytoma in three dogs:

Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical Studies.

J Comp Path.

1998; 119: 239-249.

6. Rannou B, Helie P, Bedard C. Rectal

plasmacytoma with intracellular hemosiderin in a dog.

Vet Pathol.

2009; 46:1181-1184.

7. Simmons HA. Age-associated

pathology in rhesus macaques (

Macaca mulatta).

Vet Pathol.

2016; 53(2):399-416.

8. Snyder PW. Diseases of immunity.

In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, ed.

Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease,

6th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2017:285.

9. Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM.

Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed.

Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's

Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier;

2016:109.

10. Vail DM. Plasma Cell Neoplasms. In:

Withrow SJ, Vail DM, eds.

Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 4

th

ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007: 769-784.

11. Vasudevan JA, Somanathan T, Patil

SA, Kattoor J. Primary systemic amyloidosis of tongue with chondroid

metaplasia.

J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013; 17(2): 266-268.