Signalment:

Gross Description:

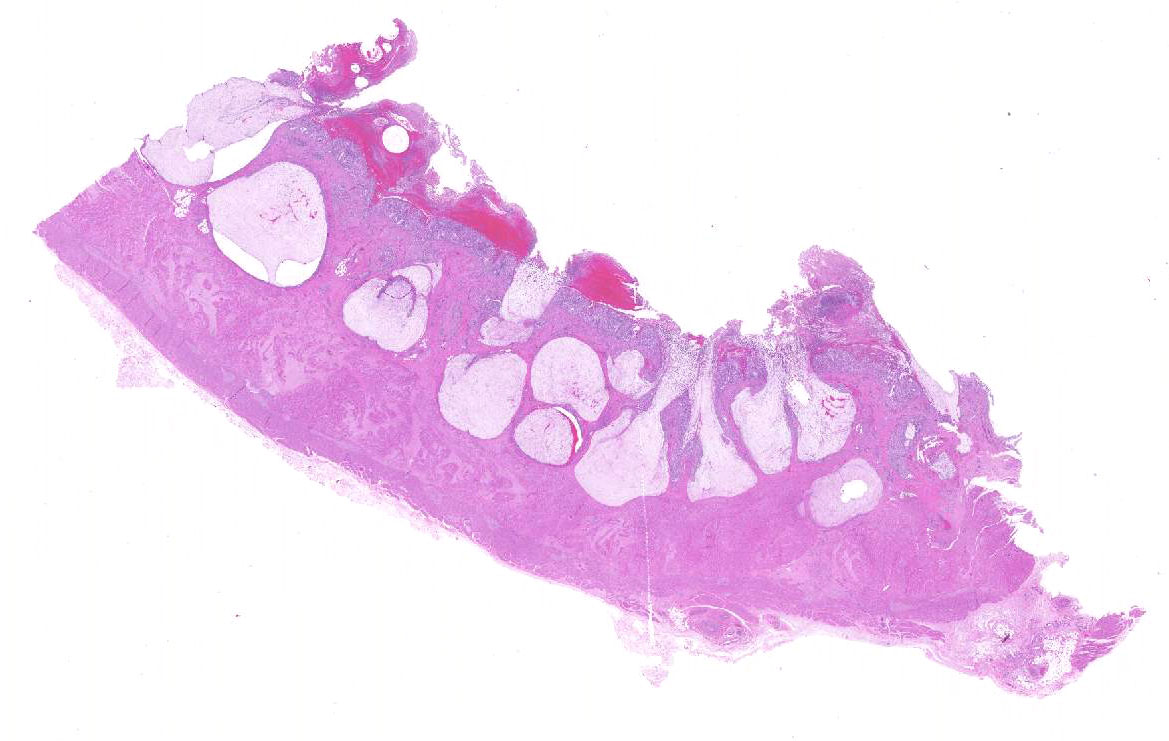

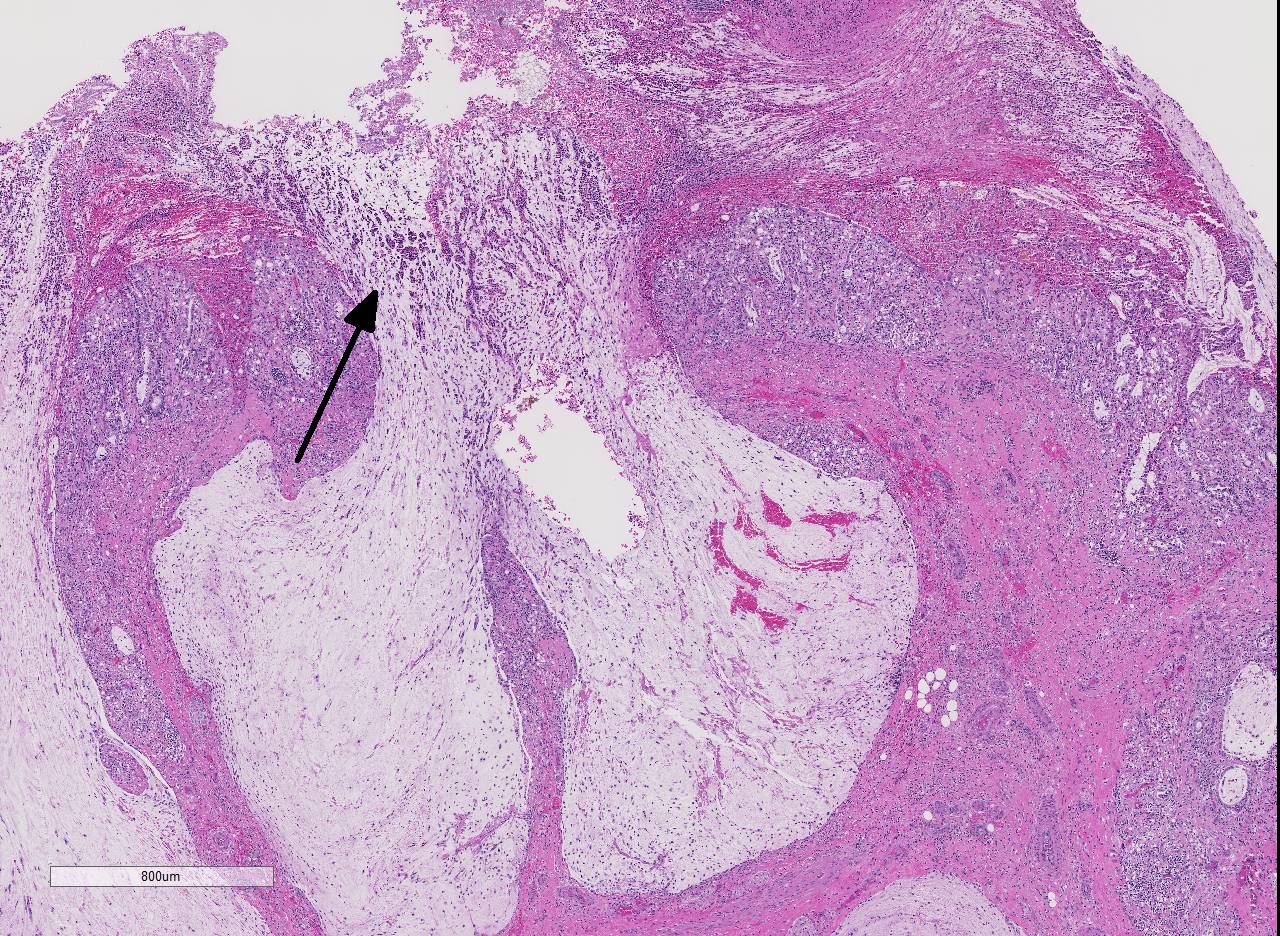

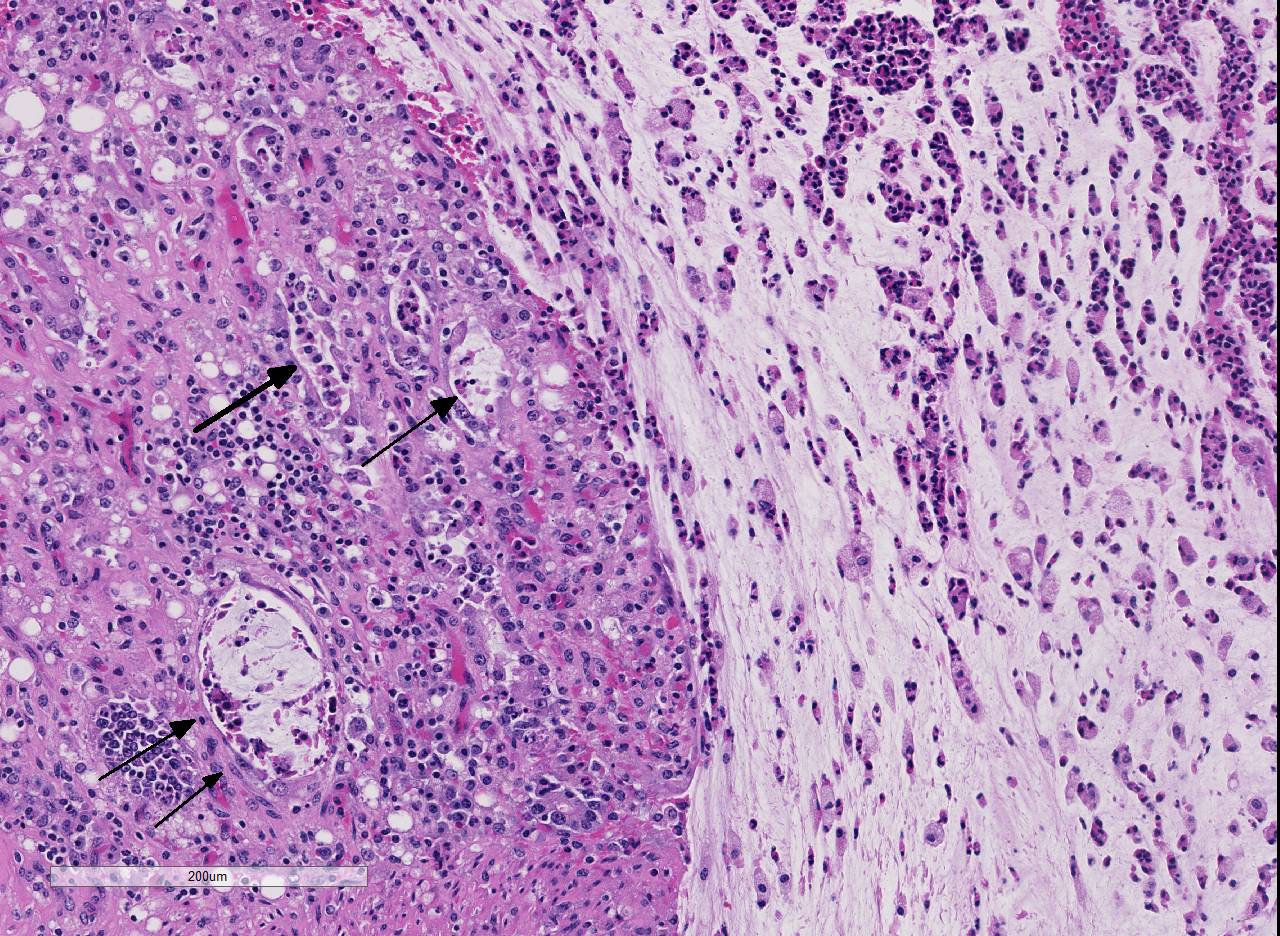

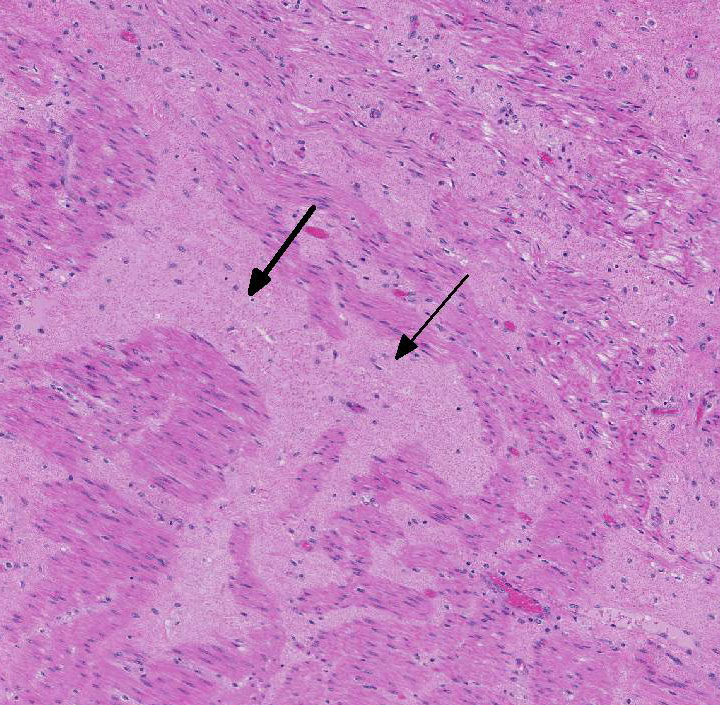

Histopathologic Description:

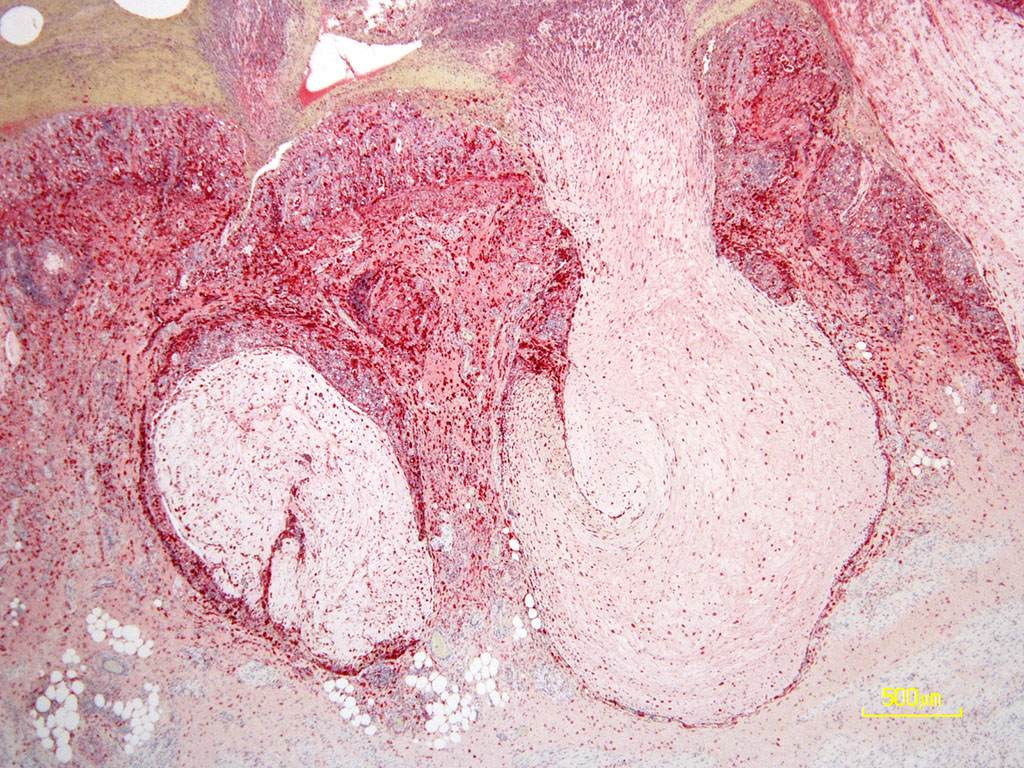

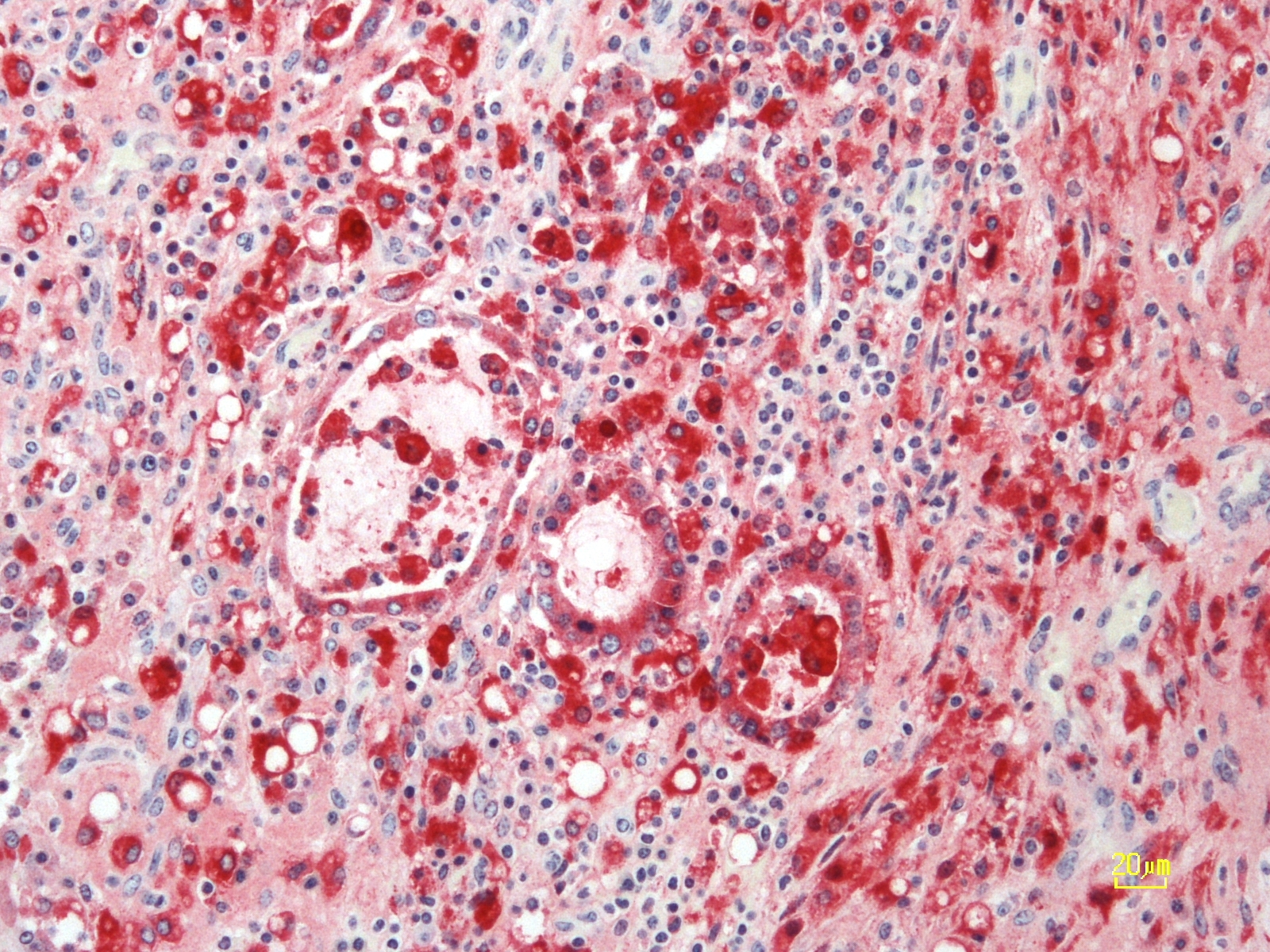

The overlying mucosa is diffusely eroded and covered by a thick layer of necrotic cellular debris admixed with numerous degenerate neutrophils, abundant fibrin, large numbers of extravasated erythrocytes, and rare bacterial colonies. The tunica muscularis is expanded by moderate amounts of edema and fibrin.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The pathogenesis and the clinical manifestations of BVDV infection in cattle are dependent on the age, immune status as well as the biological properties of the infecting strain.3 Previously described cp and ncp biotypes are closely associated with two fundamentally different forms of infection in cattle; either transient or persistent. In areas where BVDV infection is endemic, acute infection with ncp BVDV results in transient viremia with mild clinical signs that include low-grade fever, diarrhea and coughing. The infection is cleared within a few days and the seropositive animals are protected from re-infection for life. In contrast, fetal infection within second to fourth months of gestation results in immunotolerance and lifelong persistent infection. Persistently infected (PI) calves develop severe clinical disease referred to as mucosal disease that is characterized by widespread necrosis of the alimentary mucosa and lymphoid tissues. Mucosal disease only develops in PI cattle and is the result of persistent infection with a ncp strain followed by a subsequent post-natal infection with a cp strain that arise from mutation/s in already persisting ncp strain. The ability of the ncp strain to inhibit the induction of type-I interferon (IFN) in the fetus is generally believed to enable the virus to establish persistent infection. Research in last decade has identified two candidate genes that interfere with host cells IFN induction namely Erns, a structural glycoprotein with RNase activity and Npro , an N-terminal autoprotease.2

The PI calves are a major concern because they shed large amounts of virus and are an important source of infection for the uninfected animals in the herd. Control programs are specifically designed to detect and eliminate PI animals. There are a wide range of diagnostic tools available to detect virus and virus-specific immune response.4 Multiple ELISA kits are commercially available for detection of BVDV-specific antibodies in various biological samples including serum and milk. These kits are cost effective and generally used for screening large herds or conducting seroprevalence studies. It is important to note that PI infected animals are seronegative. RT-PCR is now widely accepted as a standard for BVDV diagnosis while immunohistochemistry remains one of the popular methods for antigen detection from the ear notch tissue samples.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

There are basically two forms of clinically severe BVDV in cattle. The first is mucosal disease in persistently infected cattle described by the contributor. The second is the more recently recognized severe acute BVD caused by highly virulent strains of bovine pestivirus. Viruses from both BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 species can induce severe acute BVD, however, this form is usually caused by BVDV-2.2, 6 Severe acute BVD is characterized by high morbidity and high mortality in all age groups of susceptible animals and has a peracute to acute course, with fever, sudden death, diarrhea, or pneumonia. It can also be associated with thrombocytopenic syndrome characterized by severe epistaxis, hyphema, mucosal hemorrhage, and bloody diarrhea. This syndrome is typically associated with infection by non-cytopathic high-virulence BVDV-2 species.2,6 Severe acute disease resembles both mucosal disease, malignant catarrhal fever, and rinderpest virus infection grossly. Histologically, rinderpest (Paramyxoviridae, morbillivirus) is distinguished from BVDV by the presence of intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies as well as syncytial cells. Malignant catarrhal fever (Herpesviridae, gammaherpesvirus) can be distinguished from BVDV by the appearance of the lymphoid organs; involution of lymphoid tissue occurs in BVD and lymphoproliferation occurs in MCF. 6 Regardless, antigenic or molecular characterization of the virus is required for definitive diagnosis. In this case, the contributor used immunohistochemistry, which is a highly specific modality to test for BVDV antigen in affected tissue.

In addition to persistent infection, early embryonic death, and abortion, in utero infection with bovine pestivirus can induce teratogenic lesions if a fetus is infected between 90-120 days of gestation. These lesions include: microcephaly, cerebellar hypoplasia and dysgenesis, hydranencephaly, hydrocephalus, and defective myelination of the spinal cord, microphthalmia. Other reported lesions include congenital cataracts, retinal degeneration, and optic neuritis. By day 135, the fetus is immunocompetent and will produce antibodies against the virus.6

Conference participants briefly discussed the emerging atypical pestivirus known as BVDV-3 or HoBi-like virus. This strain was recently recognized in Europe in fetal bovine serum imported from Brazil, where the disease is likely endemic. The clinical disease caused by this virus closely resembles BVDV infection, including growth retardation, reduced milk production, respiratory disease, reduced reproductive performance, and increased mortality among young animals. 1,6 In addition, commercially available BVDV diagnostic tests may not be able to detect HoBi-like viruses or to differentiate between BVDV and HoBi-like viruses. Current vaccines against BDVD have very little cross-protection against HoBi-like viruses. 1,6 Emergence of this pathogen could have negative implications for control and eradication programs for BVDV worldwide.

References:

2. Brodersen BW. Bovine viral diarrhea virus infections: Manifestation of infection and recent advances in understanding pathogenesis and control. Vet Pathol. 2014; 51:453- 464.

3. Brown CC, Baker DC and Barker IK. The alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:140-147.

4. Lanyon SR, Hill FI, Reichel MP, Brownlie J. Bovine viral diarrhoea: Pathogenesis and diagnosis. The Veterinary Journal. 2014; 199: 201- 209.

5. Schweizer M, Peterhans E1. Pestiviruses. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2014; 2:14163.

6. Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM, Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6 th ed. St. Louis, MO; Saunders Elsevier; 2016:122-127.