Signalment:

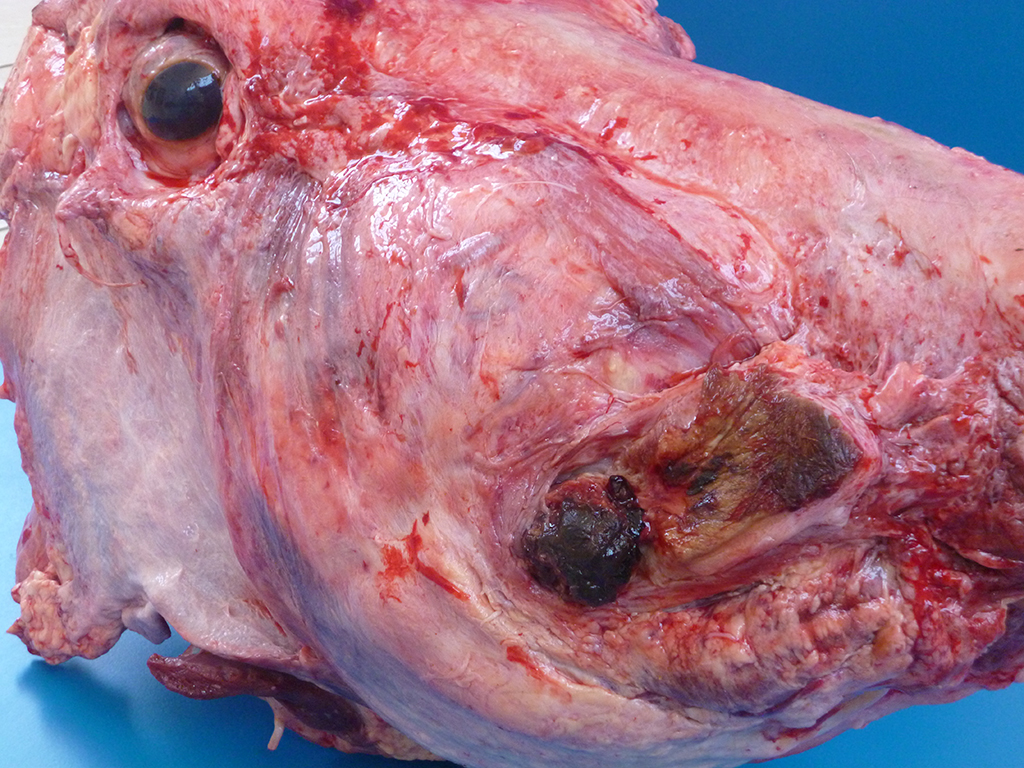

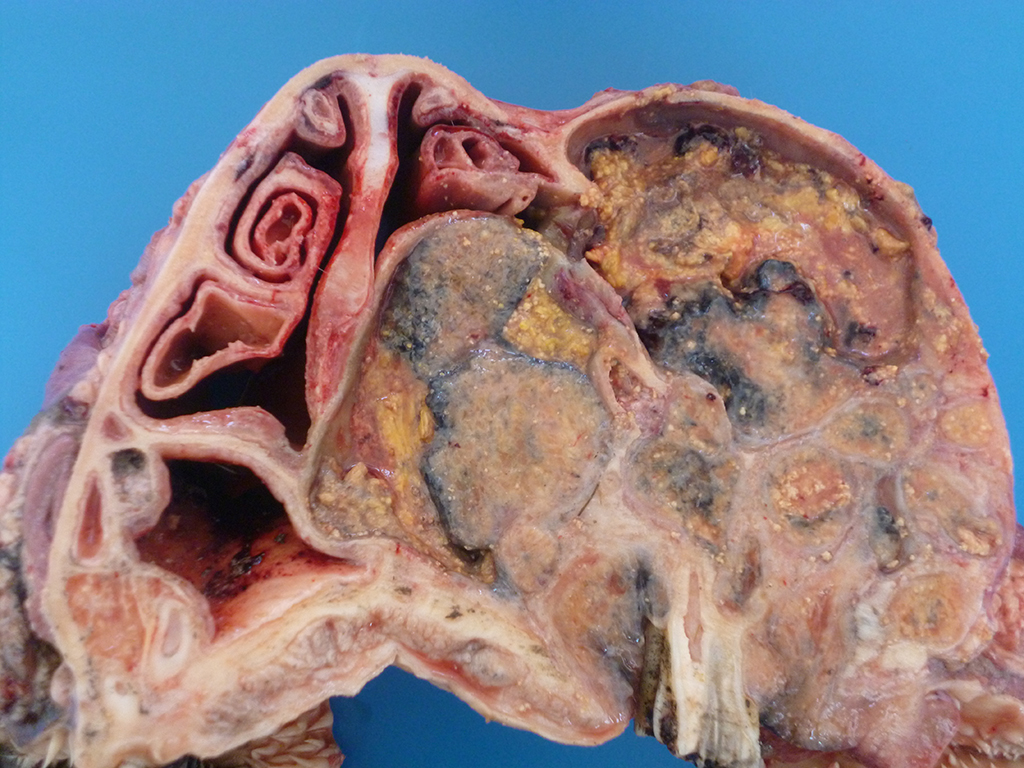

Gross Description:

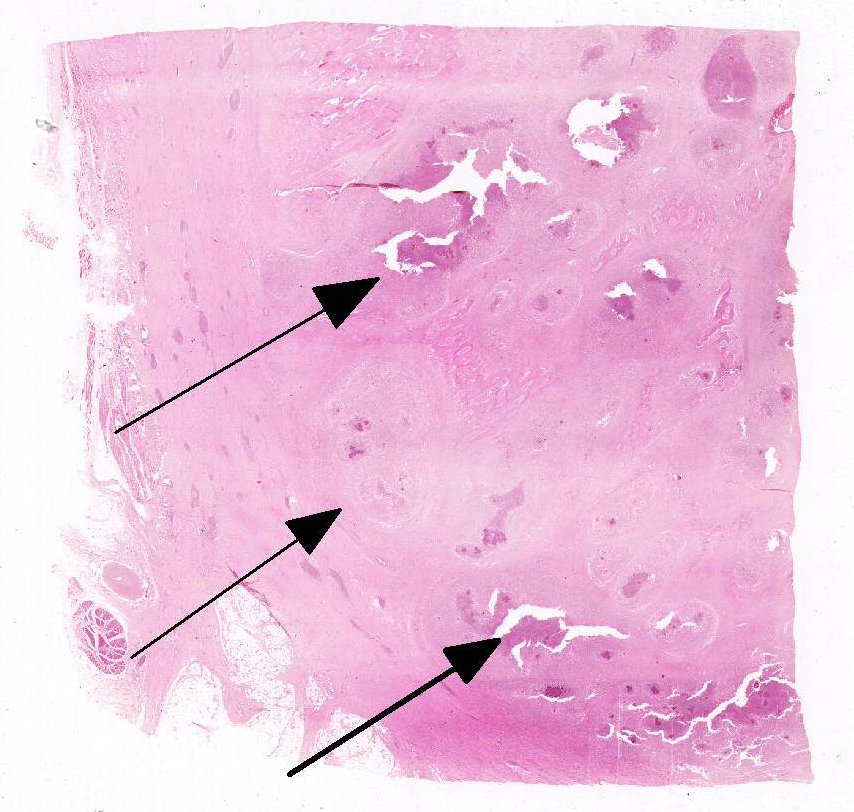

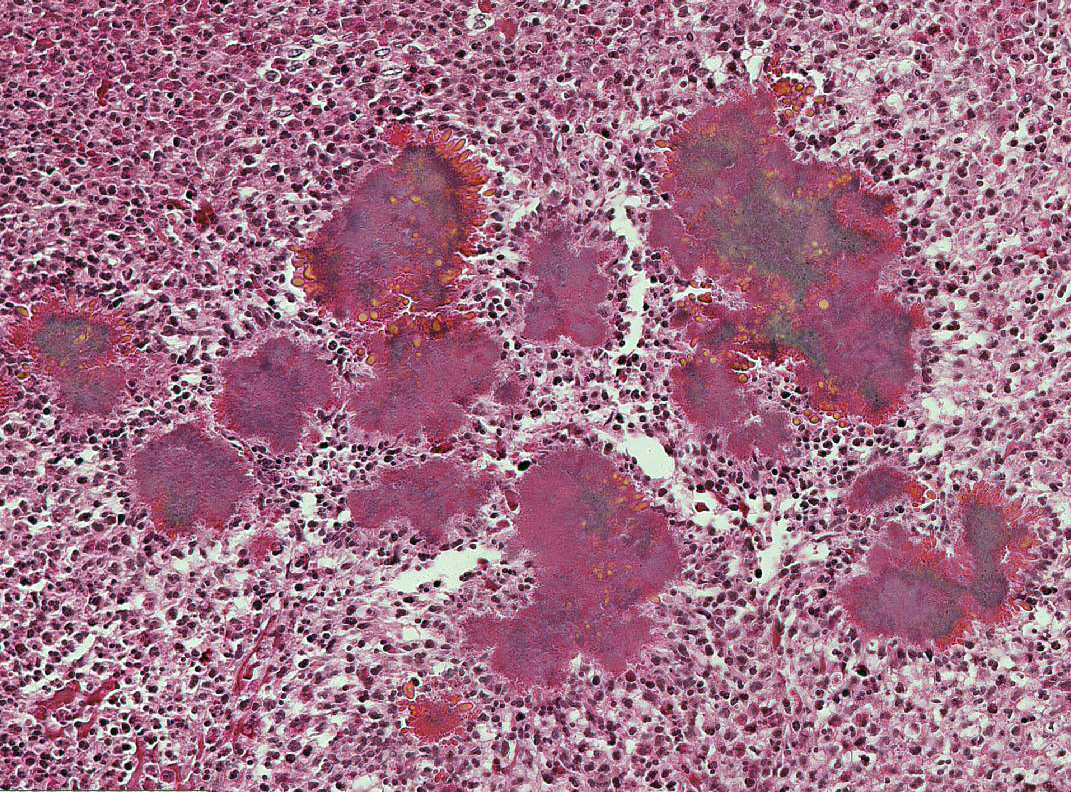

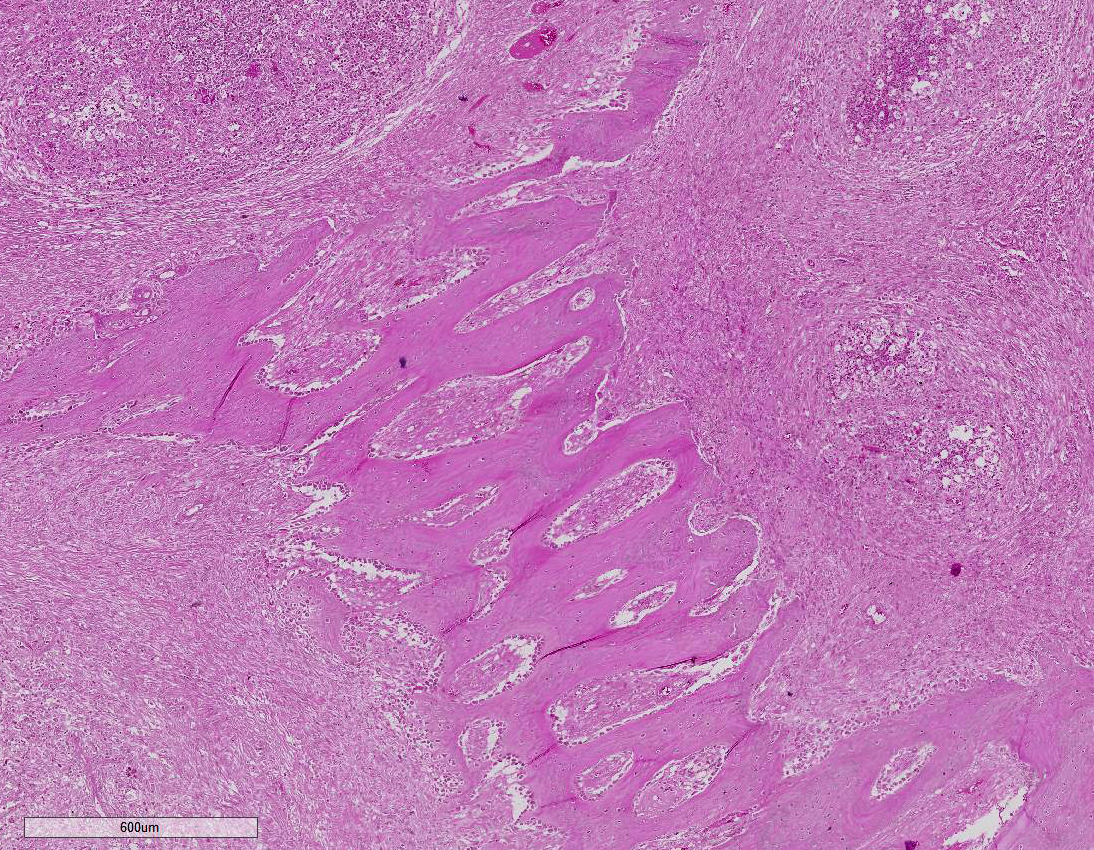

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Maxillary pyogranulomatous osteomyelitis, castrated male, mixed breed, bovine.

Etiologic diagnosis: Bacterial osteomyelitis.Etiology: Actinomyces bovis

Name of the condition: Actinomycosis.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Although actinomycosis has been described in cattle at unusual sites such as the penis and in the maxilla, as in the case presented here, the classical presentation in cattle is in the mandible and rarely in the maxilla.9,12 It is likely that the reason the mandible is the preferred site is because the direction of vegetal fibers being chewed is downwards forcing the fiber between the teeth and the gums, providing an entrance for the bacterium and resulting initially in a dental alveolitis.

Lesions of actinomycosis grow slowly over time5,12 and the involvement of the bone and muscle tissue becomes so marked that it interferes with feeding,9 which would explain the emaciation of the ox of this report. In osteomyelitis caused by actinomycosis, initially there is development of suppurative sinus tracts in the medullary spaces of the bone leading to multiple foci of both bone tissue resorption and proliferation. Bone sequestration does not occur; even if the cortical bone is invaded, probably due to the progressive course of the disease.9 The small granules – known colloquially as sulfur granules – observed grossly at the center of the caseous nodules1 represents the bacterial colonies and the associated SH phenomenon and are typical of actinomycosis, although can be seen in other pyogranulomatous diseases of cattle such as actinobacillosis and sta-phyloccocosis.8 Little is known about the virulence factors of A. bovis. The interaction between ligand-receptor in the target cells, toxins, molecules in the bacterial capsule that compromise phagocytosis, and other factors are probably involved in the pathogenicity of A. bovis. It is also probable that A. bovis is capable of escaping destruction by neutrophils and macrophages and is capable of colonizing the tissue abscesses. This peculiar resistance of the agent to phagocytosis leads to the formation – around itself – of proteinaceous eosinophilic aggregates consisting of immunoglobulins, which are observed histologically as the SH reaction.13Other bacteria induce similar tissue reactions, particularly Actinobacillus lig-nieresii. However A. bovis colonies are larger and the radiating clubs in the SH reaction are shorter and less marked that in actinobacillosis, and generally localized at the periphery of the colonies.4,8,10 Ad-ditionally, actinobacillosis is a disease of soft tissues and the microorganisms of A. lignieresii, in contrast to those of A. bovis, are gram-negative.5,8 Fusobacterium nec-rophorum and other bacteria can cause osteomyelitis by direct extension of per-iodontitis; however lesions induced by F. necrophorum are usually more destructive and less proliferative.9Grossly, a lesion such as the one described here can be mistaken for - and the lesion was initially interpreted as - a squamous cell carcinoma at the slaughterhouse. Due to great extension of the lesions and the invasive characteristics of the mass reported here, an intranasal squamous cell carcinoma should be in the top of the list as a differential diagnosis at gross examination since this is one of the tumors more frequently observed in the nasal cavity or ruminants.11 At cursory gross examination, the keratin commonly formed in these tumors may resemble the sulfur granules of actinomycosis.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

References:

1. Brewer JS. Discussion and case history: Actinomycosis. Iowa St. Univ Vet. 1956; 18:145-208.

2. Craig LE, Dittmer KE, Thompson KG. Bones and Joints. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:101.

3. Fagan DA, Oosterhius JE, Benirschke K. "Lumpy jaw" in exotic hoofstock: A histopathologic interpretation with a treatment proposal. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2005; 36(1):36-43.

4. Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Rakich PM. Skin and appendages, In: Maxie MG. ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol1. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier-Saunders; 2007: 553-781.

5. Grist A. Conditions encountered at bovine post mortem inspection (non parasitic). In: Ibid. eds. Bovine Meat Inspection. 2nd ed. Nottingham, UK: Nottingham University Press; 2008: 160-239.

6. Miller M, Haddad AJ. Cervicofacial actinomycosis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1998;85:496-508.

7. Soto E, Arauz M, Gallagher CA, Illanes O. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica as the causative agent of mandibular osteomyelitis (lumpy jaw) in a cat. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2014; 26(4):580-584.

8. Tessele B, Martins TB, Vielmo A et al. 2014. LesÕes granulomatosas Encon–tradas em bovinos abatidos para consumo. [Granulomatous lesions found in cattle slaughtered for meat production.] Pesq Vet Bras. 2014; 34:763-769.

9. Thompson K. Inflammatory diseases of bones In: Maxie MG. ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol1. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier-Saunders; 2007: 92-105.

10. Till DH and Palmer FPA. A review of actinobacillosis with a study of the causal organism. Vet Rec. 1960; 72:527-543.

11. Wilson DW, Dungworth DL. Tumors of the respiratory tract, In: Tumors in Domestic Animals. ed. Meuten DJ. 4th. Ames, IA: Iowa State Press; 2002:365-374.

12. Wilson WG. Wilson's Practical Meat Inspection. 7th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. 2005.

13. Zachary J.F. Mechanisms of microbial infections, In: Zachary JF and McGavin MD. eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier-Saunders. 2012:147-241: 2012.