Signalment:

Nearly two years prior to euthanasia, the mare presented with an approximately 10 cm diameter, rounded, boney tumor on the caudal aspect of the left mandible. The mandible was thickened in the horizontal plane, with a craterous depression immediately caudal to the mass. Radiographs revealed an altered trabecular pattern of bone extending dorsally into the mandibular cheek tooth roots.

Previous clinical history included a left-sided ethmoid hematoma diagnosed approximately eight years prior to euthanasia, which was treated with serial surgeries and formalin injection. Following complete recovery, the mare later developed a chronic, low-volume, bilateral, mucoid nasal discharge due to a mucocele, which resolved in response to 10% formalin injection. No further mucoid discharge or endoscopic changes to the ethmoid turbinates were observed following treatment. The reason for eventual euthanasia was not specified by the case contributor.

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

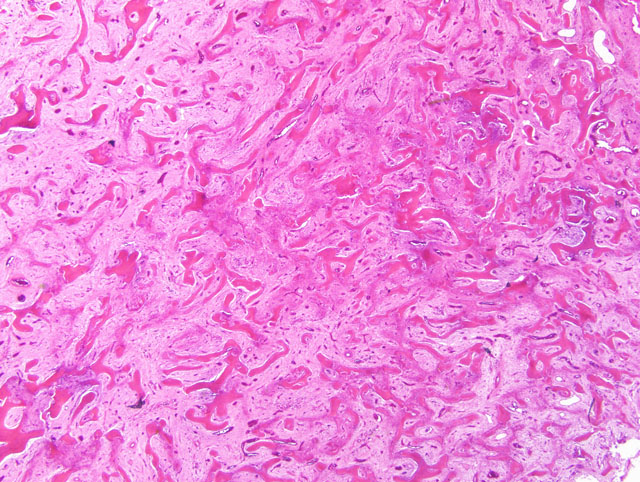

Microscopically, FOD is characterized by the triad of increased osteoclastic bone resorption, fibroplasia, and increased osteoblastic activity with the formation of trabeculae of woven bone; all three features are also seen in normal bone remodeling and certain stages of fracture repair, and are present in this case as well.(7) Therefore, the diagnosis requires correlation with the clinical and radiographic findings, and examination of sections of bone distant from sites of bone remodeling or fracture repair. The numerous osteoclasts present in this case compelled some participants to discount ossifying fibroma entirely in favor of a diagnosis of FOD; however, the conference moderator cautioned participants to remember that any mesenchymal cell can secrete RANK-L, resulting in osteoclast differentiation and activation. In this case, fibrous osteodystrophy can be excluded only in light of the clinical history and radiographic findings.

The foci of inflammation within marrow spaces seen in this case are unusual, and are not typical of FOD or ossifying fibroma, urging some participants to consider osteomyelitis in the differential diagnosis. While inflammation in the marrow spaces and reactive new bone growth may result from chronic, productive osteomyelitis, the conference moderator and participants noted several features that argue against osteomyelitis in this case: 1) inflammation in osteomyelitis would be expected to occur in larger pockets, whereas in this case the foci of inflammatory cells are small and generally confined to perivascular areas; 2) the reactive trabecular bone in osteomyelitis would generally exhibit a distinct orientation around pockets of inflammation, whereas in the examined slides the new bone is arranged haphazardly; and 3) productive osteomyelitis generally yields reactive periosteal new bone growth that is oriented perpendicular to the cortex initially (though it may orient parallel to the cortex after remodeling), and would not typically produce the degree of cortical osteoclasis seen in this case.

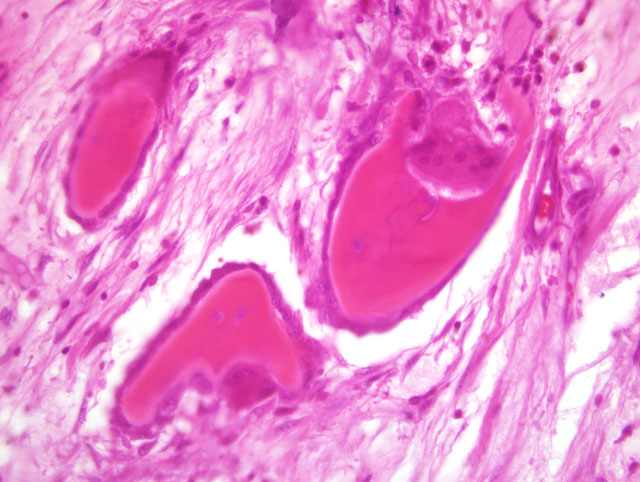

Microscopically, ossifying fibroma is often described as intermediate between fibrous dysplasia and osteoma, two other benign bone-forming tumors considered by conference attendees and discussed during the conference. Fibrous dysplasia has been ascribed to a mesenchymal developmental abnormality, hamartomatous anomaly, or neoplastic process. While relatively common in humans, it has been only rarely reported in the horse, including once in the accessory carpal bone causing sudden-onset lameness,(2) and once in the nasal cavity causing epistaxis.(3) Fibrous dysplasia closely resembles ossifying fibroma in all respects except one: while spicules of bone in ossifying fibroma are lined by a single layer of plump osteoblasts which apparently arise from the proliferating mesenchymal cells that separate them, spicules of bone in fibrous dysplasia form directly from mesenchymal cells and are not lined by osteoblasts.(2-4,6-8) At the other end of the spectrum, osteomas are composed primarily of dense trabeculae of woven bone that, as in ossifying fibroma, are lined by a layer of plump osteoblasts; however, osteomas generally project from the surface of the bone, and their bony trabeculae are more separated by smaller spaces with more loosely-arranged mesenchymal tissue than is present in ossifying fibroma.(4,6,8)

Because reports of fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, and osteoma in horses remain sparse, differences in prognosis among these benign fibro-osseous proliferations are not yet apparent, and the more practically important duty of the veterinary histopathologist is distinction between these proliferative lesions and malignant neoplasia. Affirming this, the submitting clinicians working diagnosis, based on the gross and radiographic findings, included osteosarcoma and fibrosarcoma. Osteosarcoma, while less common than ossifying fibroma in horses, is occasionally reported in the bones of the face and jaw and shares with ossifying fibroma the tendency to replace alveolar and cortical bone, causing tooth loosening and increased susceptibility to pathological fracture. Osteosarcoma is excluded in this case by the presence of regularly-spaced, irregularly-shaped spicules of welldifferentiated woven bone, a feature characteristic of ossifying fibroma but not osteosarcoma. Moreover, the spicules of bone are lined by plump osteoblasts that are clearly distinct from the proliferating mesenchymal cells that separate the bone trabeculae. In contrast to the usually overtly malignant neoplastic cells of osteosarcoma, the proliferating mesenchymal cells in this case are microscopically bland, with a low mitotic rate, minimal anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, and absence of osteoid.(4,5,7,8) Similarly, fibrosarcoma is excluded based on the bland microscopic features of the proliferating mesenchymal cells and the gradual transition between the proliferative cell population and adjacent tissue.

Finally, though not associated with the degree of cortical lysis present in this case, idiopathic enostosis-like lesions have been reported in the long bones of horses(1) and should be considered when a proliferation of woven bone is encountered in a diagnostic setting. An example from the right distal humerus of a Swedish Warmblood riding horse was reviewed in WSC 2008-2009, Conference 21, case IV.

References:

2. Jones NY, Patterson-Kane JC: Fibrous dysplasia in the accessory carpal bones of a horse. Equine Vet J 36:93-95, 2004

3. Livesey MA, Keane DP, Sarmiento J: Epistaxis in a standardbred weanling caused by fibrous dysplasia. Equine Vet J 16:144-146, 1984

4. Miller MA, Towle HAM, Heng HG, Greenberg CB, Pool RR: Mandibular ossifying fibroma in a dog. Vet Pathol 45:203-206, 2008

5. Mirkovic TK, Shmon CL, Allen AL: Urinary obstruction secondary to an ossifying fibroma of the os penis in a dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 40:152-156, 2004

6. Speltz MC, Pool RR, Hayden DW: Pathology in practice: ossifying fibroma of the right mandible. J Am Vet Med Assoc 235:1283-1285, 2009

7. Thompson K: Bones and joints. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 82-88, 110-124. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

8. Thompson KG, Pool RR: Tumors of bones. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals, ed. Meuten DJ, 4th ed., pp. 248-255, Iowa State Univ. Press, Ames, IA, 2002