WSC 22-23

Conference 21

Case III:

Signalment:

9-year-old spayed female canine (Canis familiaris)

History:

Patient presented 6 months before for a mass in the ventral neck. It was diagnosed as a possible abscess and Clavamox and Baytril were prescribed.

Today, patient presented for recheck with no improvement noted. She has difficulty walking, generalized weakness and is hesitant to move. She is painful (4/5) and anxious (4/5). Differential diagnosis includes IVDD.

Gross Pathology:

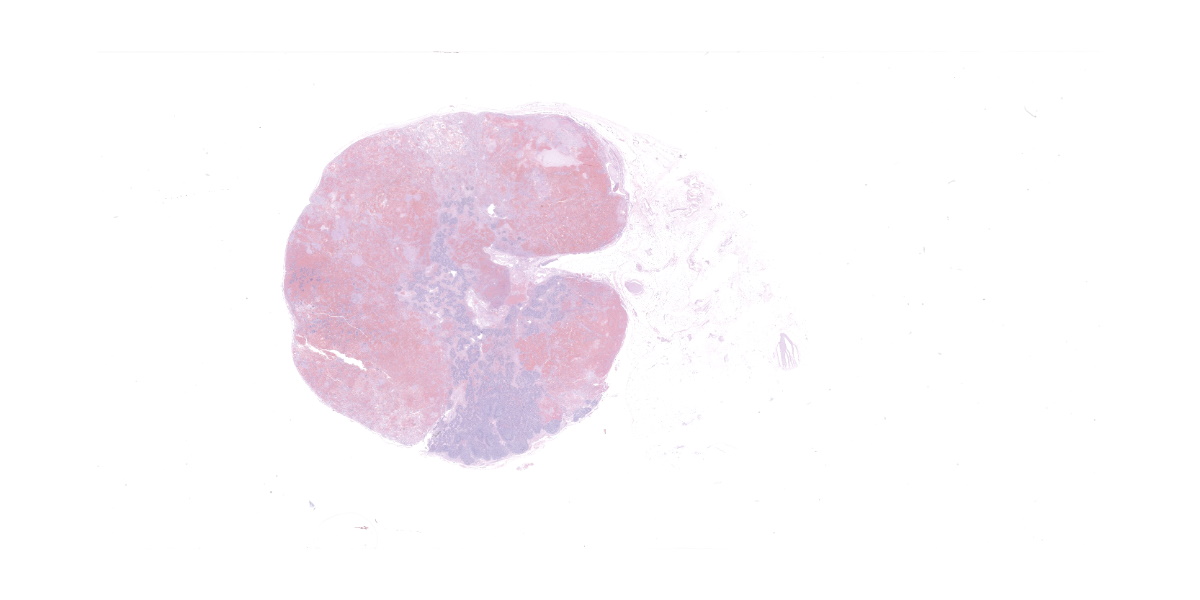

The submandibular lymph nodes are enlarged bilaterally and asymmetrically. The left lymph node (7 x 3 x 2 cm) starts at the mandibular ramus, is firm, movable and dark red in color. The right lymph node (4 x 1.5 x 1 cm) has the same appearance. The cranial mediastinal lymph nodes are dark red in color, firm and enlarged (3 x 1, 5 x 4 cm nodules). On cut section, all the affected lymph nodes are solid, firm, and diffusely red. The lymph node architecture is partially effaced.

Severe degree of spondylosis T13-L1, L2-L3, L4-L5 and L-S junction, extending into the vertebral canal. The ventral thoracic vertebrae also show a mild degree of spondylosis. No IVDD was found.

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory results reported.

Microscopic Description:

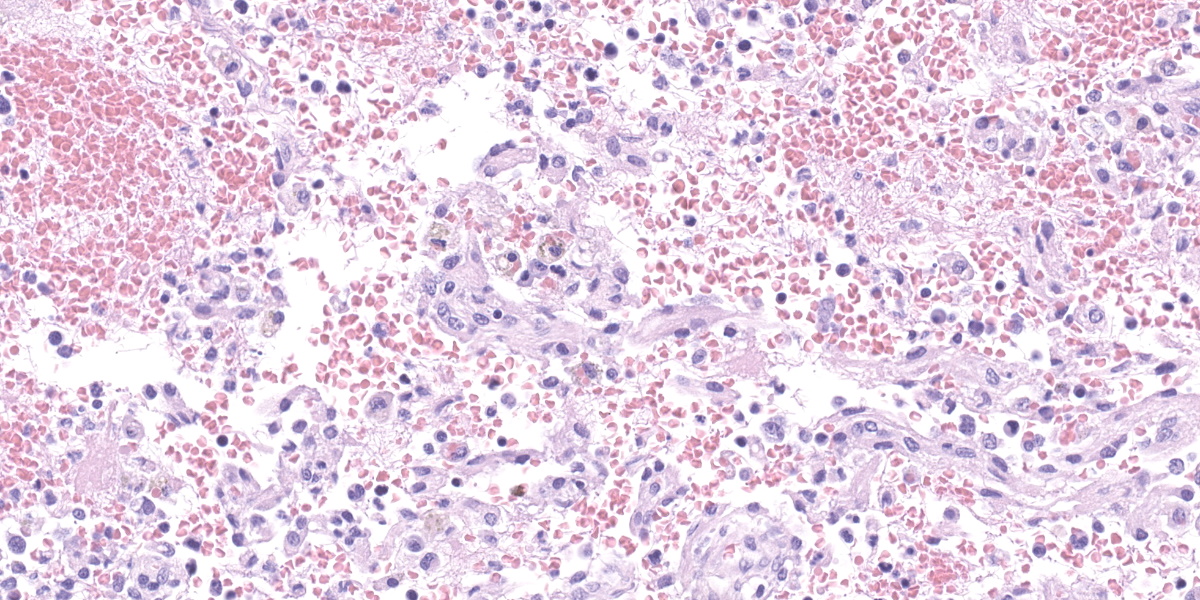

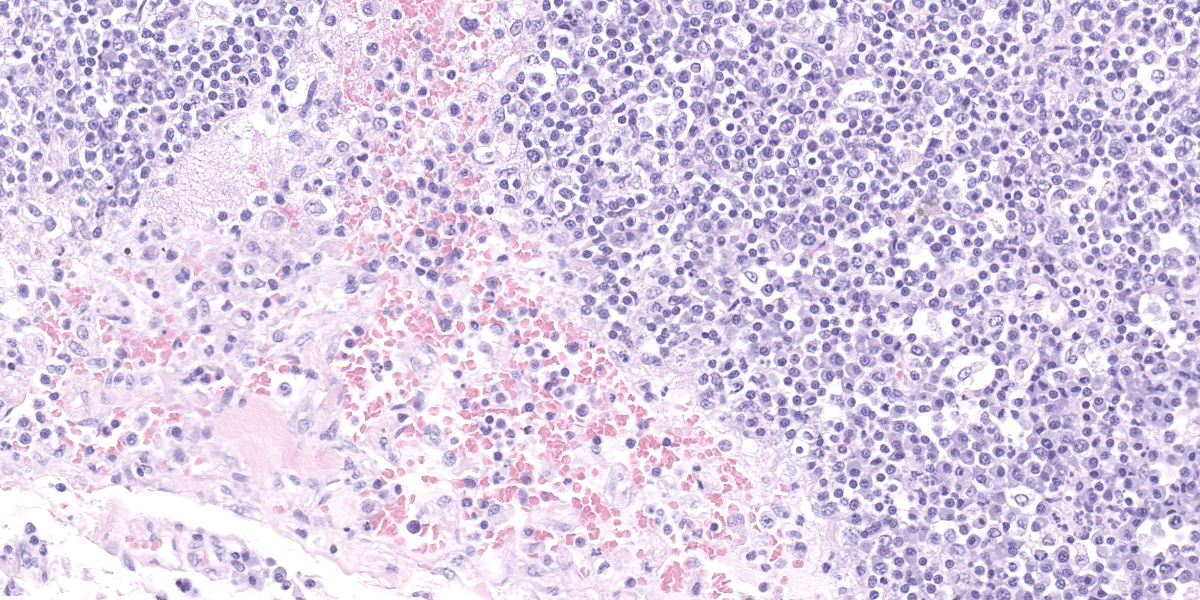

Lymph node, one section. Approximately 90% of the entire architecture is effaced by an expansile area characterized by locally extensive proliferation of anastomosing, variable sized and dilated slit openings resembling vascular channels. These channels are lined by plump endothelial cells. There are small areas of necrosis, characterized by intense eosinophilic, amorphous material, admixed with scattered macrophages, rare lymphocytes and plasma cells. These vascular channels are filled with RBCs and scattered clusters of neutrophils and macrophages. Pigment-laden macrophages are common throughout (hemosiderin). The remaining normal nodal architecture is compressed with cortex and paracortex characterized by coalescing lymphoid follicles with starry sky appearance (tingible body macrophages). The lymphoid follicles have prominent germinative centers.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

DDX: Lymph node: locally extensive vascular proliferation with lymphoid atrophy compatible with nodal plexiform vasculopathy.

Contributor’s Comment:

Benign, non-neoplastic and neoplastic vascular proliferations in the lymph nodes have been described in different animal species.

The differential diagnosis for vascular proliferations in a lymph node includes nodal angiomatosis, plexiform vasculopathy, nodal hemangioma, nodal vascular hamartoma, and nodal telangiectasis. All of them are of unknown cause and usually present as incidental, benign proliferations that will efface and replace the normal lymphoid architecture.

Plexiform vasculopathy, also known as vascular transformation of lymph nodes, is an endothelial proliferation within lymph nodes and has been reported in humans, cats, and one dog with thyroidal carcinoma.5 It is an uncommon lesion, and it is still unknown whether the proliferating endothelial cells are of lymphatic or blood origin. The literature describes it as a lymphadenopathy with vasoproliferation and lymphoid atrophy.7 The lesions are usually focal but can involve most of the lymphoid tissue. The lesions are distinct from more common findings such as lymphosarcoma, reactive lymphadenopathies, and normal lymph nodes.

The pathogenesis of this disease is unclear in both the human and animal literature. The description of plexiform vasculopathy has been limited to cats. The human equivalent to this disease is nodal angiomatosis. There is one paper that describes a lymphadenopathy in a dog associated with thyroid carcinoma. The histological description was similar to that of nodal angiomatosis and plexiform vasculopathy.3

Clinical signs are nonspecific and generally present as secondary signs to some sort of lymphadenopathy in the cervical or inguinal region. Lymph nodes are enlarged and in cross section they have a fleshy tan to purple appearance.7 Some of these signs include dyspnea, nonpainful masses, and difficulty swallowing. Histopathology shows severe loss of lymphoid tissue distributed throughout the lymph node and replaced by accumulations of erythrocytes within a capillary-like proliferation of endothelial cells. The endothelial cells are characterized by small, elongated, basophilic nuclei and inconspicuous cytoplasm. Mitotic figures were rare throughout.5,7

Cytoplasmic expression of CD31 and factor VIII-related antigens were found via immunohistochemistry in all proliferated intranodal endothelial cells. A recent study used the lymphendothelial-specific marker, Prox-1, to determine the origin of the intranodal endothelial cells. The results of this study determined that the proliferative endothelial cells were of lymphatic origin.5

There are a variety of possible pathogenic explanations for plexiform vasculopathy including disturbances in drainage caused by tumors in the lymph node, thrombosis, severe congestive heart failure, or angiogenic factors released by a neoplastic process. A similar lesion of lymphatic proliferation has been experimentally induced in rabbits via incomplete occlusion of veins combined with complete obstruction of lymphatics, or just by the complete obstruction of lymphatics.5 The later stages of human Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) is characterized by progressive lymphoid atrophy with vascular proliferation. However, the vascular proliferation associated with AIDS involves post-capillary venules with subsequent severe immune deficiency which does not occur in plexiform vasculopathy.7

Differentials should include other intranodal vascular proliferations such as angiomatous hamartoma, nodal lymphangiomatosis, hemolymph nodes, and nodal hemangiomas. However, none of these have been described in dogs.

Welsh et al. (1999) reported that complete excision of a retropharyngeal lymph node appears curative. Post-operative complications appeared to be limited to edema in the region of the excised lymph node.

Contributing Institution:

College of Veterinary Medicine, Western University of Health Sciences, 309 E. Second street

Pomona, California 91766

http://www.westernu.edu/xp/edu/veterinary/staff.xml

JPC Diagnosis:

Lymph node: Vasculopathy and hemorrhage, severe, with marked fibrin deposition and extramedullary hematopoiesis.

JPC Comment:

Two major categories of non-neoplastic vascular proliferations within lymph nodes are angiomyomatous hamartoma and vascular transformation of sinuses.8 In vascular transformation of sinuses, there is capillary proliferation within subcapsular and intermediate sinuses accompanied by variable amounts of fibrosis and lymphoid atrophy.8 Variants of vascular transformation of sinuses include plexiform vasculopathy, nodal angiomatosis in humans, and angiomatous hyperplasia in Wistar rats.8 While not completely known, vascular transformation of sinuses is thought to occur due to occlusion of lymphatic or efferent veins which causes edema in the draining region. Plexiform vasculopathy is most commonly documented in the cervical lymph nodes of cats,5,9 and in some cases, has been associated with malignant transformation to angiosarcoma.9

Angiomyomatous hamartoma, which has been documented in humans, a cynomolgus macaque, and a dog, involves proliferation of vessels with muscular walls within the cortex of the lymph node. The pathogenesis of angiomyomatous hamartoma is unknown. A recent report described the incidence of both angiomyomatous hamartoma within the hilus and vascular transformation within the subcapsular and medullary sinuses in the cranial mediastinal lymph nodes of a 1-year-old beagle in a toxicity study.8

This case generated significant discussion among the moderator and conference participants. In some regions of the node, the presence of well-defined plexiform channels is consistent with nodular plexiform vasculopathy. In other regions, collagen and smooth muscle actin within vascular walls (confirmed via histochemical and immunohistochemical staining) are more prominent than would be expected in plexiform vasculopathy but not enough to be consistent with a diagnosis of angiomyomatous hamartoma. The moderator and conference participants also discussed another prominent feature of this case: hemorrhage and fibrin thrombi. Participants discussed how polymerized fibrin can induce endothelial proliferation and fibrosis, and in this case, might serve as a potential cause for secondary vasculopathy within the node. Thus, hypercoagulability (i.e. due to protein losing nephropathy) was discussed as a potential differential.

Another differential considered less likely by the moderator and participants is neoplastic transformation. Hemangiomas are generally well circumscribed and expansile,8 features which are lacking in this case. Hemangioendothelioma and hemangiosarcoma also feature a high mitotic rate, cellular atypia, and invasion.8 Additionally, primary vascular neoplasia within lymph nodes is uncommon; in a study of 439 vascular tumors in dogs, only one primary tumor occurred in a lymph node, and only 2 of 63 angiosarcomas metastasized to lymph nodes.2 In a separate study of 175 beagles that were controls in a toxicology study, however, hemangiomas were found incidentally in 9 popliteal and 1 hepatic lymph node, demonstrating that these may not be as uncommon as the literature suggests.4

Another feature discussed by the moderator and participants in this case is extramedullary hematopoiesis, consisting of lymphoid and erythroid precursors, megakaryocytes, and nurse cells.

References:

- Fuji RN, Patton KM, Steinbach TJ, Schulman FY, Bradley GA, Brown TT, Wilson EA, Summers BA. Feline systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis: eight cases and literature review. Vet Pathol. 42: 608-17.

- Gamlem H, Nordstoga K, Arnesen K. Canine vascular neoplasia - a population based clinicopathologic study of 439 tumors and tumour-like lesions in 420 dogs. APMIS. 2018; Suppl 125: 41-54.

- Gelberg HB, Valentine BA. Diagnostic exercise: Lymphadenopathy associated with thyroid carcinoma in a dog. Vet Pathol. 2011; 48(2), 530-534.

- HogenEsch H, Hahn FF. Primary vascular neoplasms of lymph nodes in the dog. Vet Pathol.1998; 35(1): 74-76.

- Jungwirth N, Junginger J, Andrijczuk C, Baumgärtner W, Wohlsein P. Plexiform vasculopathy in feline cervical lymph nodes. Vet Pathol. 2018; 55 (3), 453-456.

- Karim MS, Ensslin CJ, Dowd ML, Samie FH. Angiomyomatous hamartoma in a postauricular lymph node: A rare entity masquerading as a cyst. JAAD Case Reports. 2021; 7:131.

- Lucke V, Davies JD, Wood CM, Whitbread TJ. Plexiform vascularization of lymph nodes: an unusual but distinctive lymphadenopathy in cats. J Comp Pathol. 1987; 97: 109-119.

- Nelissen S, Chamanza R. An Angiomyomatous Hamartoma With Features of Vascular Transformation of Sinuses in the Mediastinal Lymph Node of a Beagle Dog. Toxicol Pathol. 2020; 48(8), 1017-1024.

- Roof-Wages E, Spangler T, Spangler WL, Siedlecki CT. Histology and clinical outcome of benign and malignant vascular lesions primary to feline cervical lymph nodes. Vet Pathol. 2015; 52(2), 331-337.

- Welsh EM, Griffon D, Whitbread TJ. Plexiform vascularization of a retropharyngeal lymph node in a cat. J Small Anim Pract. 1999; 40(6):291.