WSC 22-23:

Conference 4 Case 4

Signalment:

17-year-old, female spayed, domestic shorthair cat (Felis catus)

History:

The patient presented for evaluation of progressive weight loss and inappetence. Recent increase in seizure activity. Newly diagnosed pulmonary mass, presumptive pulmonary carcinoma. Historical small cell lymphoma, chronic rhinitis, hyperthyroidism, acute cerebral infarction.

Clinical Diagnosis:

- Historical acute cerebral infarction

- Stable small cell lymphoma

- Pulmonary carcinoma

- Hyperthyroidism

- Chronic idiopathic rhinitis

- Acute exacerbation of neurologic signs

- Progressive weight loss - metastatic disease

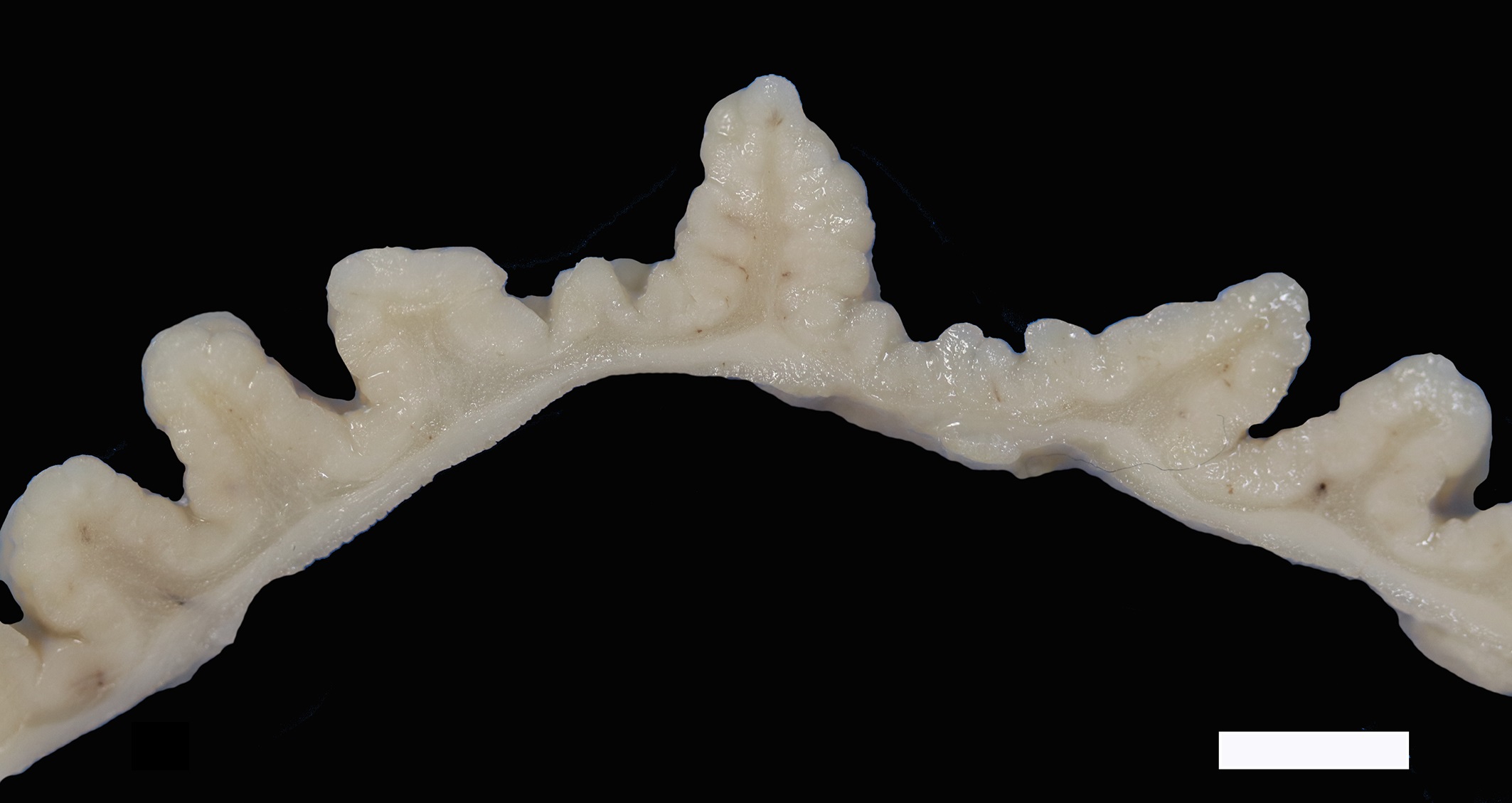

Gross Pathology:

The mucosa of the body of the stomach is markedly expanded by irregular, cobblestone-like thickening of the gastric rugae (rule out neoplasia vs proliferative gastritis vs lymphofollicular hyperplasia. The irregular mucosal thickening up to 2.5 mm can be appreciated within the mucosa upon sectioning of the fixed tissue.

Laboratory Results:

Abdominal ultrasound of the stomach was normal.

Microscopic Description:

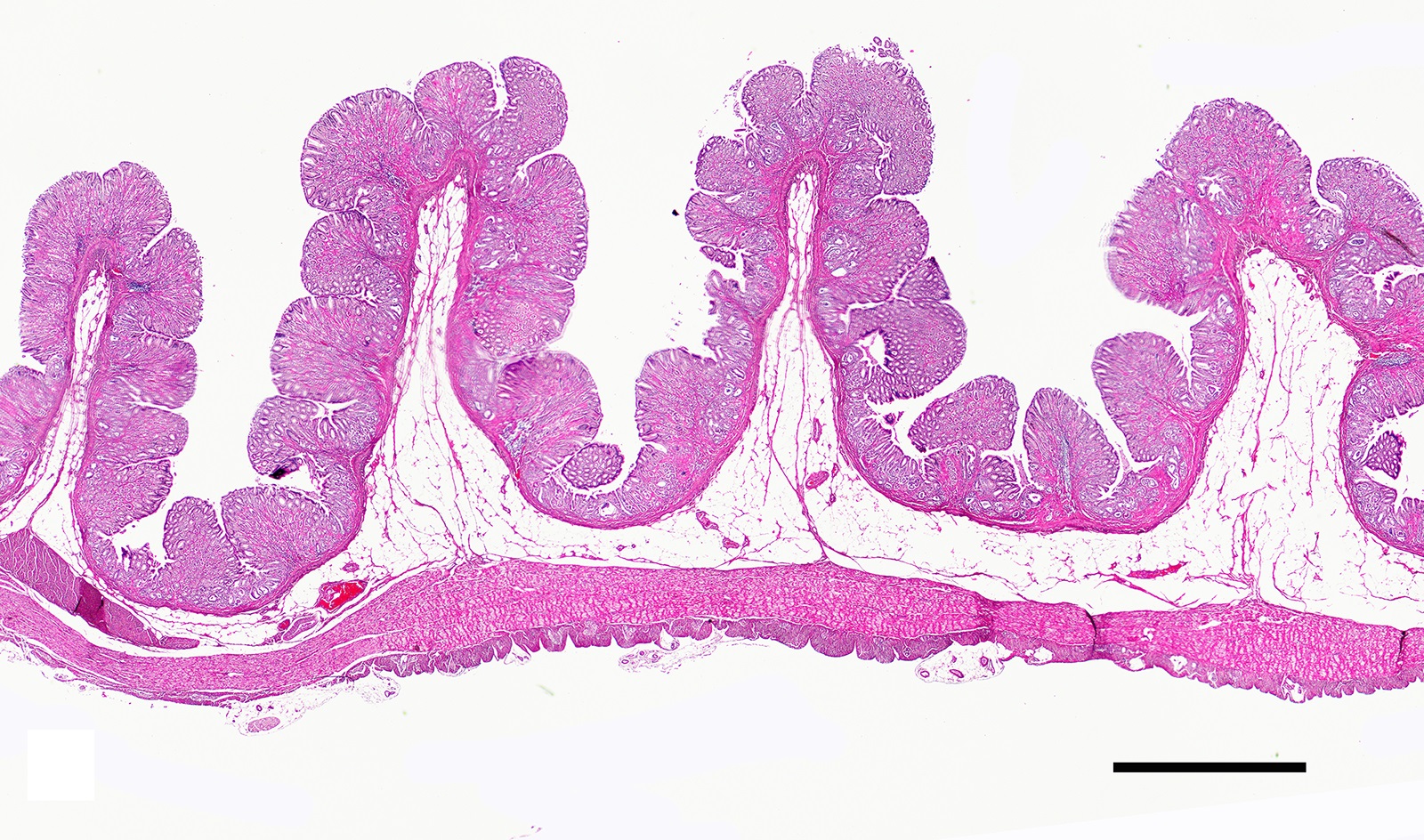

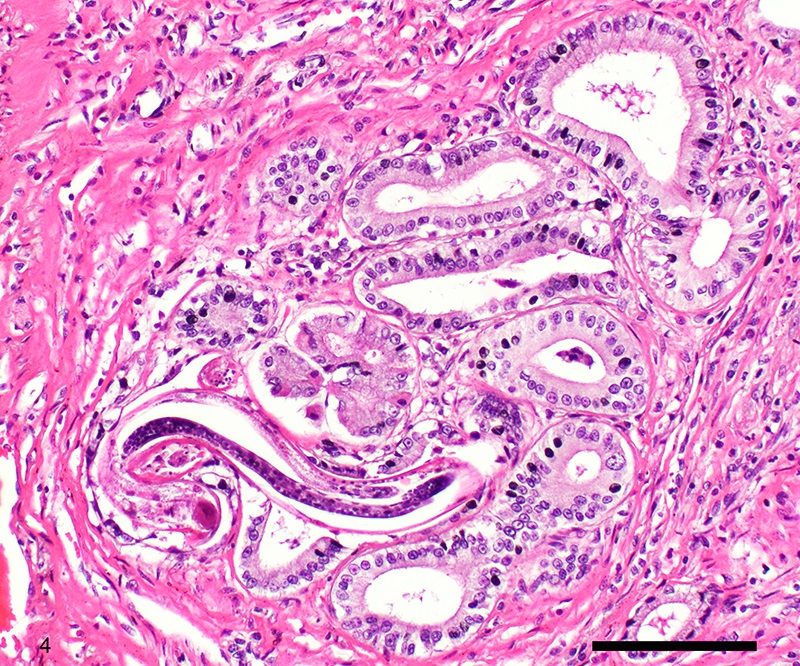

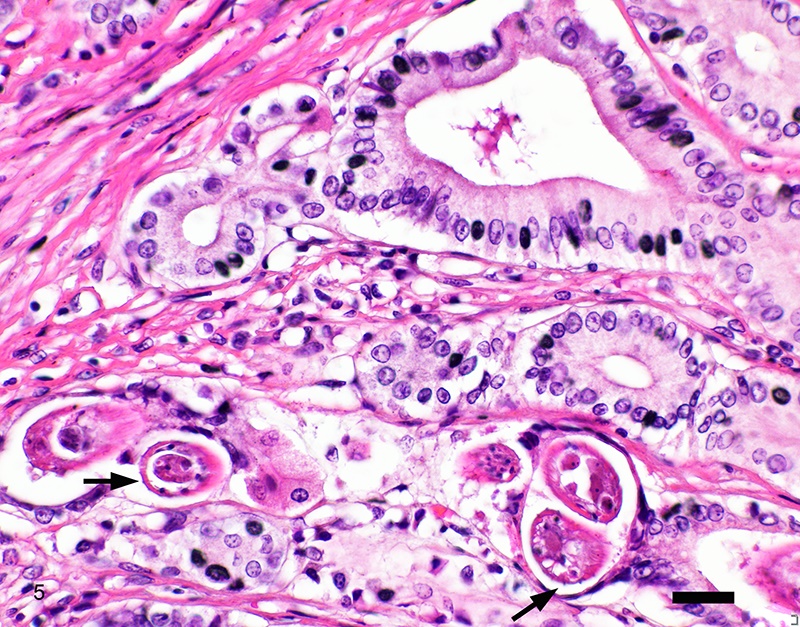

Two sections of gastric wall from the body/pylorus of the stomach are examined. The mucosa is highly folded and increased in thickness, measuring up to 2 mm. The thickened mucosa comprises increased numbers of gastric pits lined by abundant mucus containing epithelial cells (mucus neck cells) which are typically lined by a single epithelial cell, but multifocally pile up to 2-3 cell layers thick. Chief and parietal cells are present but comprise a minority of the mucosal area. There are increased numbers of inflammatory cells throughout the lamina propria, with ectatic gastric glands and frequent glandular and luminal nematode parasites. Nematode parasites range from 20-30 um in diameter, with regularly arranged, evenly spaced cuticular spicules. These parasites have platymyarian-meromyarian musculature, a pseudocoelom with a large intestine composed of few multinucleated cells and reproductive structures. Moderately increased amounts of fibrous connective tissue are noted throughout the lamina propria, sometimes concentrically surrounding and separating glands that contain nematode parasites. Inflammation consists of predominantly lymphocytes with fewer plasma cells, macrophages and eosinophils throughout the lamina propria. Lymphocyte aggregates are occasionally present without formation of follicular structures. Multifocally, ectatic gastric glands contain sloughed cells and necrotic cell debris with occasional nematode parasites. The lining glandular epithelium of these dilated glands is multifocally attenuated. The submucosa contains adipose tissue (within normal limits for spp).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Stomach: Gastritis, proliferative, lymphocytic, chronic, marked with fibrosis, luminal and glandular nematode parasites (morphology consistent with Ollulanis tricuspis)

Contributor’s Comment:

The grossly identified cobblestone-like thickening of the stomach mucosa corresponds with proliferative gastritis and nematode parasitism. Numerous nematode parasites observed throughout the mucosa were histologically consistent with trichostronglyes, for which Ollulanus tricuspis is given primary consideration.6 Confirmatory ancillary tests were not performed. Ollulanis tricuspis is a small (0.7-1.0 mm length) trichostronglyid nematode with worldwide distribution.4 This parasite is typically found in the stomach of domestic cats but has been reported in large, non-domestic felids (including captive cheetah, tigers, lions and cougars), dogs, red foxes and pigs.2,4,5,7,10 Ollulanis tricuspis has a direct life cycle, transmitted by ingestion of infected vomitus.2,4,5,7-10 No paratenic or intermediate hosts have been identified.5 O. tricuspis is larviparous, third stage (L3) larvae developing in the uterus. L3s eliminated in the vomitus are thought to be infective and can remain viable for up to 12 days. A single sample of vomitus can contain 0 to greater than 170 parasites.5,7 Feral and colony-raised cats may have a higher likelihood of being infected due to the concentration of numerous cats in a small area.9 It has been suggested that infected long-haired cats are more likely to transmit the parasite because of more frequent vomiting due to a higher tendency to develop gastric trichobezoars.8,9

Infection with this parasite is frequently incidental.4 The parasite is thought to increase gastric mucus production.7 Clinical signs, when present include anorexia, weight loss and intermittent vomiting, however heavy infections can cause severe gastritis, neoplastic transformation and rarely death.4,10 Vomiting has been reported as the most common clinical sign.4 This patient had multiple concurrent comorbidities, some of which could also present with vomiting (e.g. intestinal small cell lymphoma), however, gastrointestinal signs were not listed as a prominent clinical concern in the historical summary. Despite the large numbers of parasites and prominence of the gastric mucosal proliferation, infection with this parasite was most likely incidental.

In felids with O. tricuspis parasitism, the gross appearance of the stomach can vary, depending upon the severity of the infection, ranging from macroscopically normal to grossly evident gastritis with mucosal hyperplasia and rugal thickening.8 In one study, only 1 of 26 cats infected with O. tricuspis had grossly visible gastric lesions.9 Reported histologic lesions include mucosal hyperplasia, mucosal erosion, fibrosis, increased mucosal lymphoid aggregates (some of which display large germinal centers) and increased globule leukocytes.7,8,9,12 In this case, gastritis predominantly comprised lymphocytes with lymphocyte aggregates but no formation of follicular structures. Increased globule leukocytes were not observed. Mucosal proliferation is attributed to hyperplasia of mucus containing epithelial cells of the gastric pits. Parasites were generally observed within gastric glands as well as the gastric lumen. Fibrosis was also noted, sometimes concentrically surrounding glands with luminal parasites. Fibrosis was more prominent in the deeper portions of the stomach, just superficial to the muscularis mucosa, as has been previously reported.8

Other nematode parasites reported in the stomach of cats include Gnathostoma sp, Cylicospirura felineus, Physaloptera, Cyathospirura sp, Aleurostrongylus abstrusus, Spirocerca lupi, Aonchotheca putorii, other Trichostronglyus spp and oxyurids of prey animals (e.g. mice).4,5,12 The demonstration of regular cuticular spicules is considered a key distinguishing morphologic feature of adult O. tricuspis.4,6,9 These small parasites can be easily overlooked (both at postmortem examination and clinical examination of vomitus), thus the occurrence may be underestimated, as parasites or eggs are not typically present in feces.4 Adult O. tricuspis usually die due to the high pH of the small intestine and are digested before excretion into the feces.5 Small worm burdens may lead to difficultly observing or identifying parasites in histologic samples. In studies involving postmortem examination of stomach samples, worms were only identified in half the cats with O. tricuspis in three histologic sections, however, all cats had inflammatory changes consistent with O. tricuspis infection.9 Thus, pathologists should carefully evaluate samples of gastric mucosa in which the typical histologic features of O. tricuspis infection are observed. A differential diagnosis in captive cheetah is infection with gastric spiral bacteria (Helicobacter spp) which can chronic gastritis.5 Antemortem methods of diagnosing infections with this parasite include antemortem gastric washings or gastric mucosal scrapings in addition to obtaining endoscopic biopsies. Postmortem peptic digestion of stomach samples can also be performed.5,7

Contributing Institution:

Animal Medical Center, 510 East 62nd St. New York, NY 10065, www.amcny.org

JPC Diagnosis:

Stomach, pylorus: Gastritis, proliferative, chronic, diffuse, moderate, with mucous neck cell hyperplasia, glandular atrophy, and luminal and intraglandular trichostrongyle adults and larvae.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a thorough report on this nematode in the stomach of cats. As the contributor mentions, low O. tricuspis burdens can make histopathologic examination an insensitive means of detection of the parasite, and the absence of parasites in histologic sections may lead pathologists searching for other differentials. One rare non-parasitic differential which causes similar histologic lesions is chronic hypertrophic gastritis, or Ménétrier’s-like disease. In this condition, gastric rugae are diffusely thickened with variable cystic glandular dilation.1, 11 Histologically, there is mucous cell hyperplasia and atrophy of the oxyntic glands coupled with a mononuclear infiltrate within the mucosa.1, 11 While Ménétrier’s disease and its canine equivalent are rarely reported, there is only a single report of a similar condition in a cat.1 The patient was a young adult domestic shorthair cat with a history of chronic weight loss and increased appetite.1 Gastric biopsies showed mucosal hypertrophy with variable cystic glandular dilation, glandular atrophy, fibrosis, and lymphoplasmacytic inflammation.1 While no evidence of parasitism was observed on histology, the patient in this report was euthanized without necropsy, so the authors were unable to conduct ancillary testing to rule out O. tricuspis. 1

As the contributor mentions, Ollulanis nematodes and eggs are rarely found in feces; thus, a few unique methods can be used to detect infection. Antemortem diagnosis typically involves cytologic examination of gastric fluid collected through gastric lavage or induction of emesis.3 The specimen is centrifuged or filtered through a Baermann apparatus prior to cytologic examination, which has an estimated sensitivity of 70%.3 In post-mortem specimens, rice-grain sized scrapings collected from various areas of the gastric mucosa are mixed with saline (and KOH if needed) and examined cytologically.3 Peptide-digestion can also be conducted, but is more laborious and involves everting and soaking the entire stomach in pepsin digestion fluid at 37 degrees Celsius for up to 8 hours and examining the sediment for nematodes.3

References:

- Barker EN, Holdsworth AS, Hibbert A, Brown PJ, Hayward NJ. Hyperplastic and fibrosing gastropathy resembling Ménétrier disease in a cat. JFMS Open Rep. 2019;5(2)1-7.

- Bell AG. Ollulanus tricuspis in a cat colony. N Z Vet J. 1984 Jun;32(6):85-7.

- Bowman DB, Hendrix CM, Lindsay DS, Barr SC. Feline Clinical Parasitology. Ames, IO: Iowa State University Press. 2002; 263.

- Cecchi R, Wills SJ, Dean R et al. Demonstration of Ollulanis tricuspis in the stomach of domestic cats by biopsy. J Comp Pathol 2006. 134:374-77.

- Collett MG, Pomroy WE, Guilford WG, et al. Gastric Ollulanus tricuspis infection identified in captive cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) with chronic vomiting. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2000 Dec;71(4):251-5.

- Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology;1999:22-26.

- Guy, P A. Ollulanis tricuspis in domestic cats – prevalence and methods of postmortem diagnosis. New Zealand Vet J. 1984. 32(6):81-84.

- Hargis AM, Prieur DJ, Blanchard JL. Prevalence, lesions and differential diagnosis of Ollulanis tricuspis infection in cats. Vet Pathol. 1983. 20:71-79.

- Hargis, A M, Prieur DJ, Blanchard JL, et al. Chronic fibrosing gastritis associated with Ollulanus tricuspis in a cat. Vet Pathol 1982. 19: 320-323.

- Kato D, Oishi M, Ohno K, et al. The first report of the ante-mortem diagnosis of Ollulanis tricuspis infection in two dogs. J Vet Med Sci. 2015. 77(11):1499-1502.

- Uzal FA, Plannter BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2013; 53.

- Veterinary Systemic Pathology Online: https://www.askjpc.org/vspo/show_page.php?id=ejYyVGcraFE3alY5cGFWeXJtdVVzZz09