Signalment:

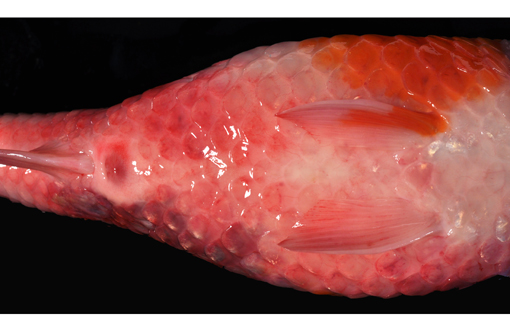

Upon clinical examination, ulceration on the lateral trunk and prominent edema of the gills were noted. Post mortem gill biopsy and skin scrapings were done using light microscopy immediately on arrival, and revealed gill flukes (Dactylogyrus sp.). Skin scraping did not reveal additional findings.

The fish was submitted for full necropsy to rule out viral, including koi herpes virus (KHV, Cyprinid herpesvirus 3), spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV), or bacterial infections. Fresh samples of gill and kidney were tested for KHV and carp edema virus (CEV). The molecular techniques used were PCR as described by Oyamatsu T. et al., for CEV and Taqman - PCR for KHV by Bercovier H. et al. A sample of water from the pond was submitted for toxicological and other water quality analyses.

Gross Description:

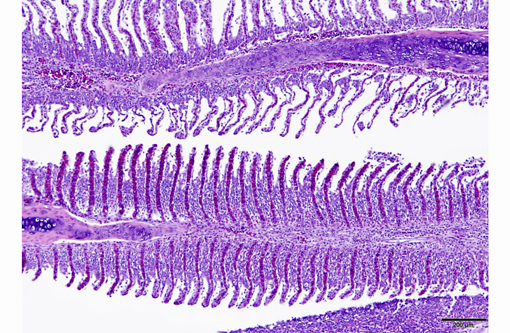

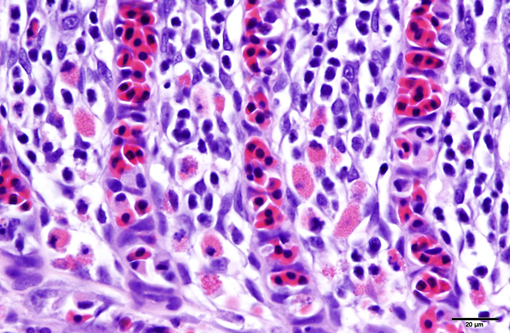

Histopathologic Description:

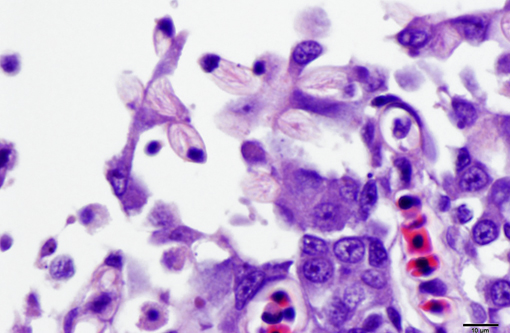

Skin (slide not provided): Associated with superficial areas of ulceration are small, gram-negative bacterial aggregates (presumed Aeromonas sp.) mixed in with rare gram-positive larger rods. Adjacent to the ulcerated regions, on the intact epidermal surface, there were thin pyriform protozoa attached by thin stalks (flagella), approximately 6x5 μm (similar in size to a red blood cell), consistent with Ichthyobodo sp., (formerly known as Costia sp.). The scales are elevated above the dermis by clear spaces (edema). Skeletal muscles in the region of skin ulceration are inflamed and necrotic. The myocytes have fragmented, vacuolated or pale eosinophilic sarcoplasm with loss of distinct striations. Mononuclear inflammatory, often fragmented cells aggregate between myocytes, and along with erythrocytes spill onto the exposed surface.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

2. Integument, mid left dorso-lateral body wall: Severe multifocal subacute regionally extensive ulcerative and fibrinohemorrhagic dermatitis and necrotizing myositis with epidermal protozoal parasites (probable Ichthyobodo sp.).

3. Integument: Severe diffuse edema, petechiation, scale loss and lymphocytic and granulocytic dermatitis.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In this case, the diagnosis of carp edema virus was made on the characteristic gross and histologic findings with confirmation by PCR. No virions were identified in gill tissue by electron microscopy; however, the tissue was not optimally preserved. Combination of CEV, protozoal, and bacterial infections may have played a role in the skin ulceration. The latter two could potentially be opportunistic pathogens infecting the compromised host.Â

Based on the history (mild water temperature, season, age of affected fish) and gross lesions (skin ulcerations and petechiae), differentials for this case would include KHV and SVC. The pronounced branchial edema distinguishes the CEV infection, grossly. As a brief review, KHV is characterized grossly by necrotizing branchitis and is a reportable disease of wild and cultured common carp. Histological findings include epithelial proliferation, fusion of the gill lamellae, and epithelial necrosis (cytopathic effect of the virus). Typical of KHV, there are intranuclear inclusions in many cell types, including but not limited to respiratory epithelial cells, macrophages, hematopoietic cells in the kidney, and cardiac myocytes. Electron microscopy demonstrates enveloped herpes virus with mature nucleocapsids measuring up to 117nm and mature enveloped nucleocapsids up to 180nm in the affected cells.(7) KHV virus can be isolated from multiple organs and confirmed with PCR and immunohistochemistry.(2,5) Spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) from the family Rhabdoviridae, genus Vesiculovirus, is the causative agent of another reportable, contagious, fatal disease of farmed carp and related species. The virus causes petechial hemorrhages in the gill and skin, as well as internal hemorrhage in the kidneys, spleen and liver, and exophthalmia. SVCV targets the swim bladder, resulting in edema and inflammation, as well as ascites.(1,3) Skin ulceration can also be caused by parasitic infection such as Ichthyobodo sp. (formerly known as Costia sp.) that may also affect the gills.(4,9) The latter agent can be seen on scrapings from gills and skin lesions, and on histological examination. Koi ulcer disease (also known as summer ulcer disease and carp erythrodermatitis), associated with bacterial pathogens such as Aeromonas spp., can also present similarly.(4,9)

JPC Diagnosis:

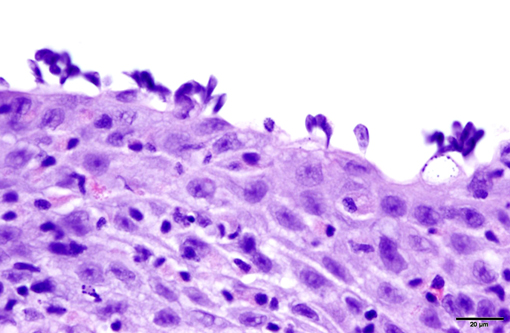

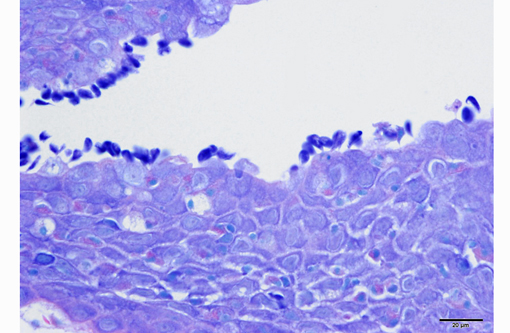

1. Gill: Branchitis, proliferative, diffuse, severe, with marked epithelial hypertrophy and hyperplasia, lamellar fusion, arteriolar fibrin thrombi and mild goblet cell hyperplasia.

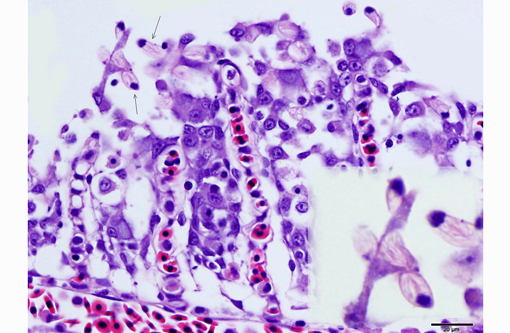

2. Oral mucosa: Stomatitis, proliferative and lymphocytic, diffuse, mild, with numerous intraepithelial intranuclear inclusions.

Conference Comment:

Gas exchange occurs via countercurrent exchange at the surface of the secondary lamellae, which are lined by overlapping squamous epithelial cells, usually one layer thick, surrounding numerous capillaries that are supported by rows of pillar cells. Where the pillar cells encroach on the basement membrane, they spread to coalesce with neighboring pillar cells to complete the lining of lamellar blood channels. Pillar cells contain contractile protein elements that resist distension and support the lamellar blood spaces. The surface of the lamellar epithelium gives rise to microvilli that aid in attachment of the epidermal (cuticular) mucus. This mucus, in addition to providing protection against abrasion and infection, is important in the exchange of gas, water and ions. The combined thickness of the cuticle, respiratory epithelium and flanges of the pillar cells (which is the total diffusion distance for gas exchange) ranges from 0.5 to 4 μm. Low to moderate numbers of goblet cells are scattered among lamellar squamous epithelial cells of both primary and secondary lamellae.(8)

Much like mammalian lungs, the gill epithelium is thin with a large surface area in order to maximize the exposure of gill capillaries to water. While this is an important factor for efficient gas exchange, it is a fairly ineffective physical barrier and results in increased branchial vulnerability to inflammation and infection. Gills also play an essential role in regulating the exchange of salt and water, as well as the excretion of the nitrogenous wastes (primarily ammonia). Thus, even minimal damage can result in significant osmoregulatory and respiratory difficulties.(8)

As noted by the contributor, the proliferative nature of these microscopic lesions is striking, with marked epithelial cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia leading to lamellar fusion; however, many conference participants also identified moderate numbers of fairly prominent, eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusions within the epithelium of the (presumed) oral mucosa, which appear to peripheralize the chromatin. After scrupulous examination of H&E sections, and consideration of the laboratory results reported by the contributor (molecular analysis for koi herpes virus was negative), we are unable to elucidate the nature of these inclusions. There is also some slide variation - not all sections contain fibrin thrombi within arterioles of the gill arch, as reflected in the JPC morphologic diagnosis. Furthermore, the moderator observed that cartilage of the gill arch appears somewhat irregular and deformed, which may suggest a previous nutritional deficiency, but is probably unrelated to the current disease process.

References:

1. Ahne W, Bjorklund HV, Essbauer S, et al. Spring viremia of carp (SVC). Dis of Aquat Org. 2002;52:261272.Â

2. Bercovier H, Fishman Y, Nahary R, et al. Cloning of the koi herpesvirus (KHV) gene encoding thymidine kinase and its use for a highly sensitive PCR based diagnosis. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:13.

3. Dikkeboom AL, Radi C, Toohey-Kurth K, et al. First report of spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) in wild common carp in North America. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health. 2004;16:169178.

4. Ferguson HW. Systemic Pathology of Fish. 2nd ed. London, UK: Scotian Press; 2006:55, 72-73.

5. Ilouze M, Dishon A, Kotler M. Characterization of a novel virus causing a lethal disease in carp and koi. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2006;70:147156.

6. Miyazaki T, Isshiki T, Katsuyuki H. Histopathological and electron microscopy studies on sleepy disease of koi (Cyprinus carpio koi) in Japan. Dis of Aquat Org. 2005;65:197207.

7. Miyazaki T, Kuzuya Y, Yasumoto S, et al. Histopathological and ultrastructural features of koi herpesvirus (KHV)-infected carp Cyprinus carpio, and the morphology and morphogenesis of KHV. Dis of Aquat Org. 2008;80:111.

8. Mumford S, Heidel J, Smith C, Morrison J, MacConnell B, Blazer V. Fish Histology and Histopathology. US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Conservation Training Center. http://nctc.fws.gov/resources/course-resources/fish-histology/index.html. Accessed April 26, 2014.

9. Noga EJ. Fish Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. St. Louis, MO: Wiley-Blackwell; 1996:108-110, 141-146.