CASE 4: N13-1267 (4048726-00)

Signalment:

1 year old male Arabian horse (Equus caballus)

History:

This colt presented with a 24 hour history of watery diarrhea, fever, and colic with worsening signs as time went on despite Banamine therapy. The colt arrived down and thrashing within the trailer, with large amounts of diarrhea present. Physical exam showed severe dehydration, purple mucous membranes, CRT >3 seconds, heart rate 90 bpm, and no gastrointestinal sounds. This colt was sedated, an IV catheter was placed, and he was anesthetized with Valium for transportation into the veterinary medical teaching hospital. A quick scan of the abdomen showed very large, stacked loops of non-motile small intestine. Humane euthanasia was elected due to worsening signs and poor prognosis. There was a postmortem interval of 2 days before necropsy was performed.

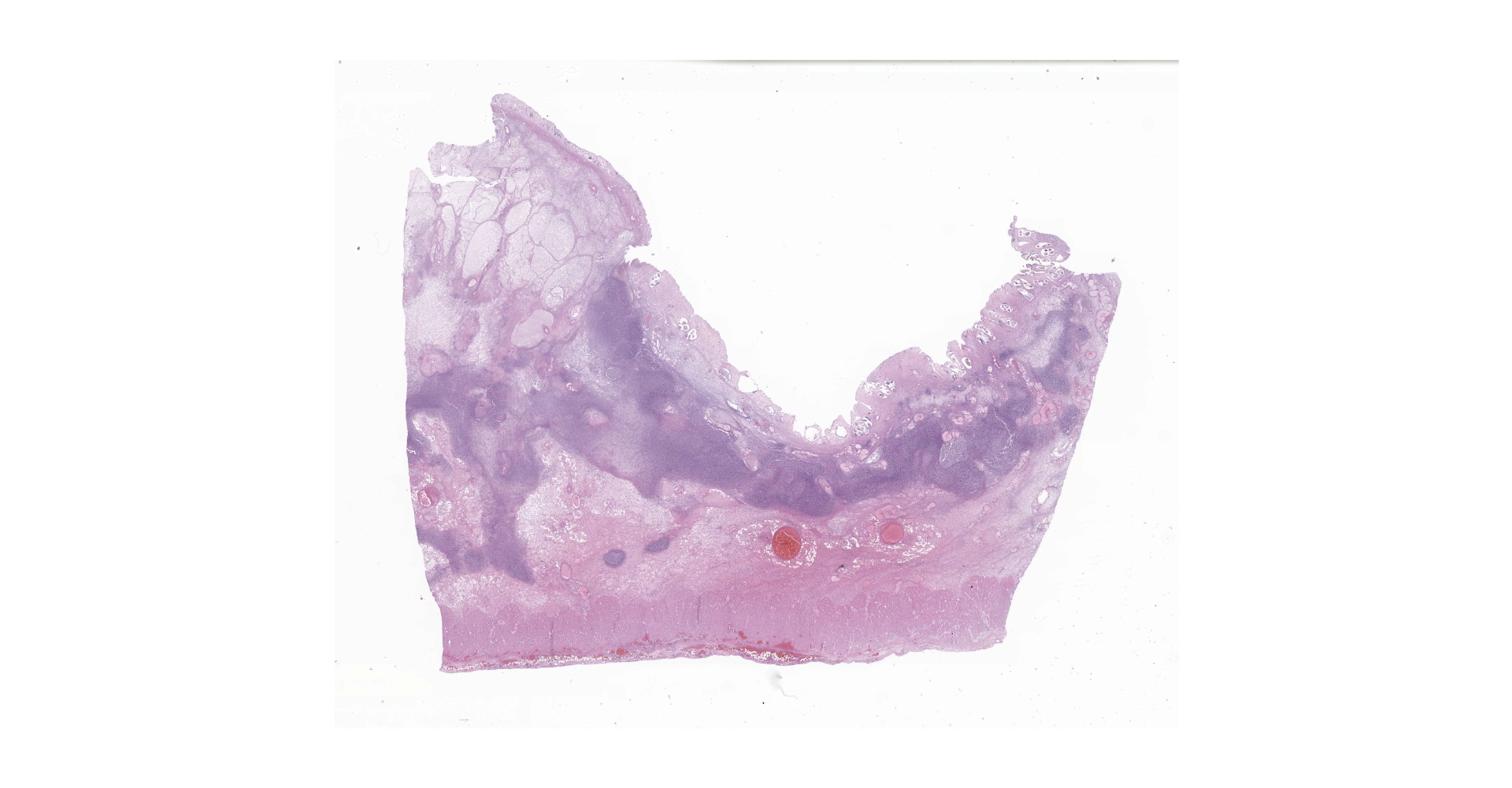

Gross Pathology:

There is approximately 2 liters of non-clotting serosanguineous fluid in the abdomen. The right ventral colon is markedly thickened, and the serosa is diffusely red-purple to black. The mucosa of the right ventral colon is thrown into markedly thickened and edematous, polypoid to nodular folds each measuring approximately 5 cm x 3.5 cm x 4 cm and are multifocally black mottled white (necrotic). The left ventral colon is also severely edematous (approximately 1 cm thick). The left ventral colon and cecum contain small numbers of tapeworms (Anoplocephala perfoliata) and approximately 10-15 proglottids. The serosa of the cecal apex is diffusely red-purple but is unremarkable on cut section. The colonic lymph nodes are moderately enlarged. There are two ulcers in the stomach located at the Margo plicatus. One is circular (approximately 5 cm x 3 cm) while the other is linear (approximately 9 cm x 0.5 cm).

Laboratory results:

N/A

Microscopic description:

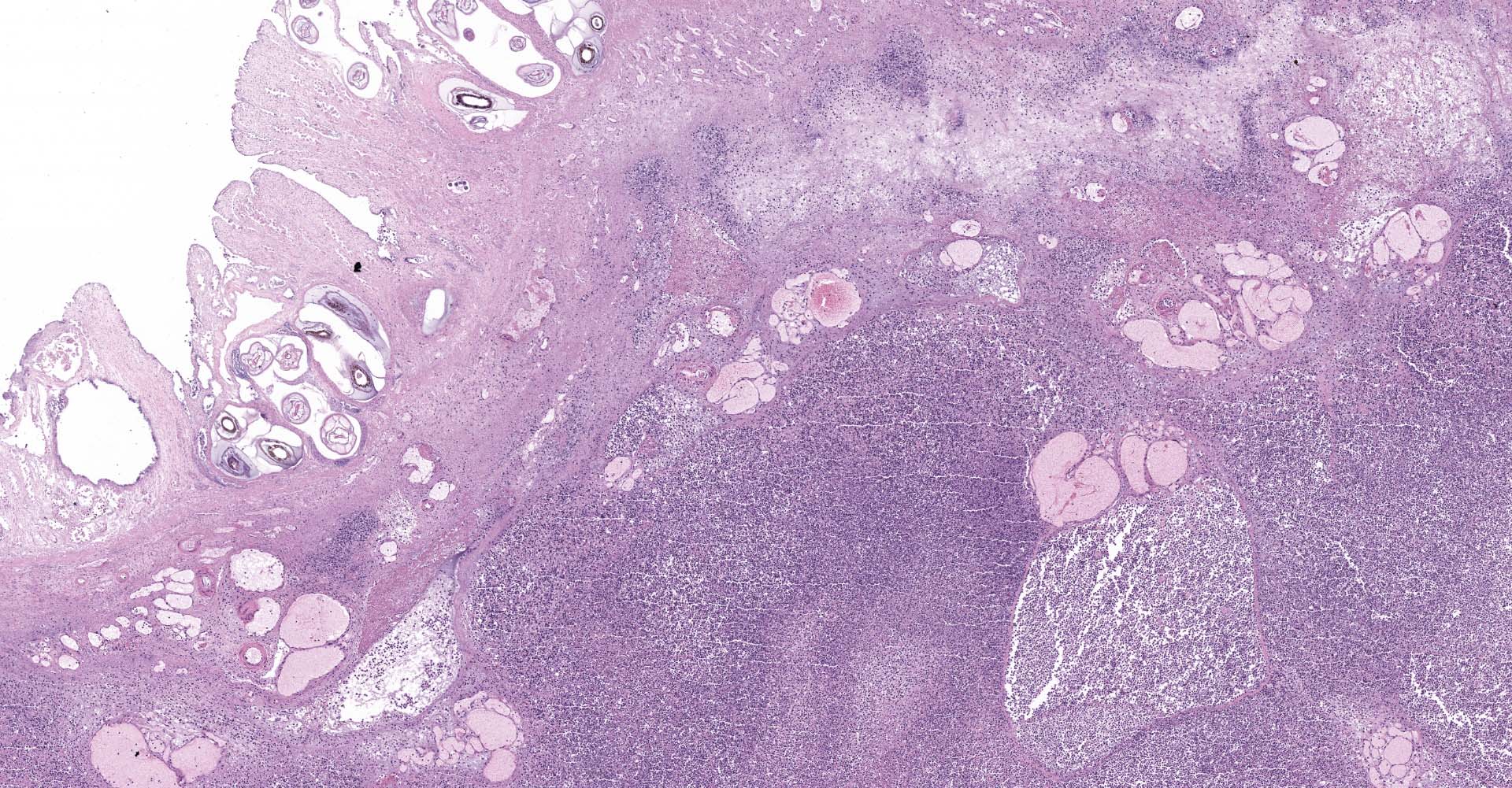

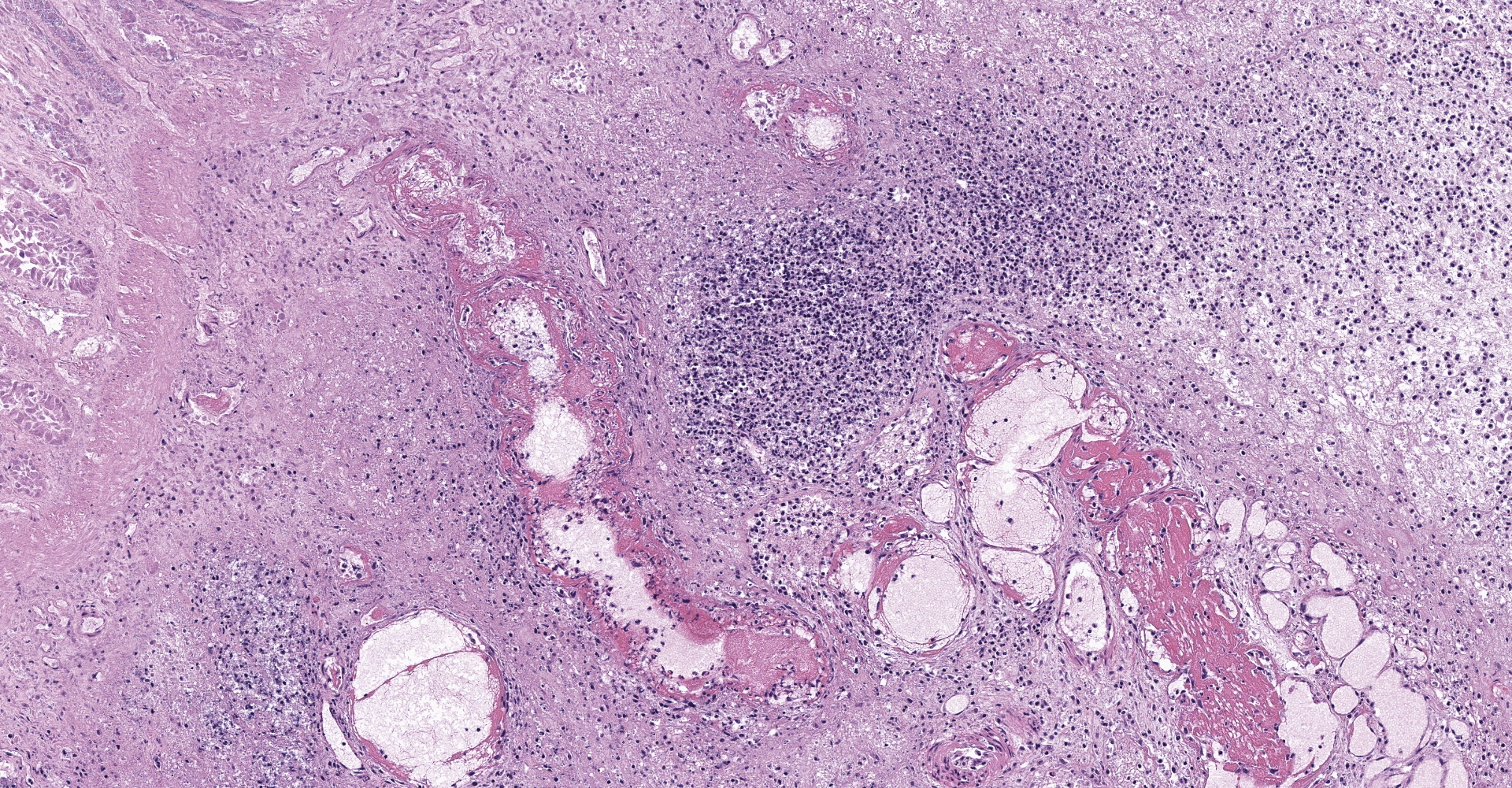

Right ventral colon: The submucosa is markedly thickened (up to 1.8 cm) by clear space (edema), abundant extracellular eosinophilic fibrillar material (fibrin), and multifocal areas of eosinophilic cellular and karyorrhectic debris (necrosis). Many macrophages intermixed with and surrounding large nodules to vast coalescing sheets of numerous of degenerate and non-degenerate neutrophils densely infiltrate the submucosa. The submucosal and tunica muscularis blood vessels are largely intact and congested, with a few scattered blood vessels containing partially occlusive fibrin thrombi. Often the thrombosed blood vessel walls segmentally contain brightly eosinophilic smudgy material with a loss of distinct wall layers (fibrinoid vascular necrosis). Incidentally, the tunica intima of muscular arteries often contains multiple irregular mineralized nodules that protrude into the lumen and are lined by endothelial cells (intimal bodies). There are multifocal foci of moderate amounts of hemorrhage, necrotic debris and inflammatory cells within the serosa. There is infiltration by numerous short and long bacilli bacteria, predominately in the mucosa but also scattered throughout the submucosa, tunica media, and serosa.

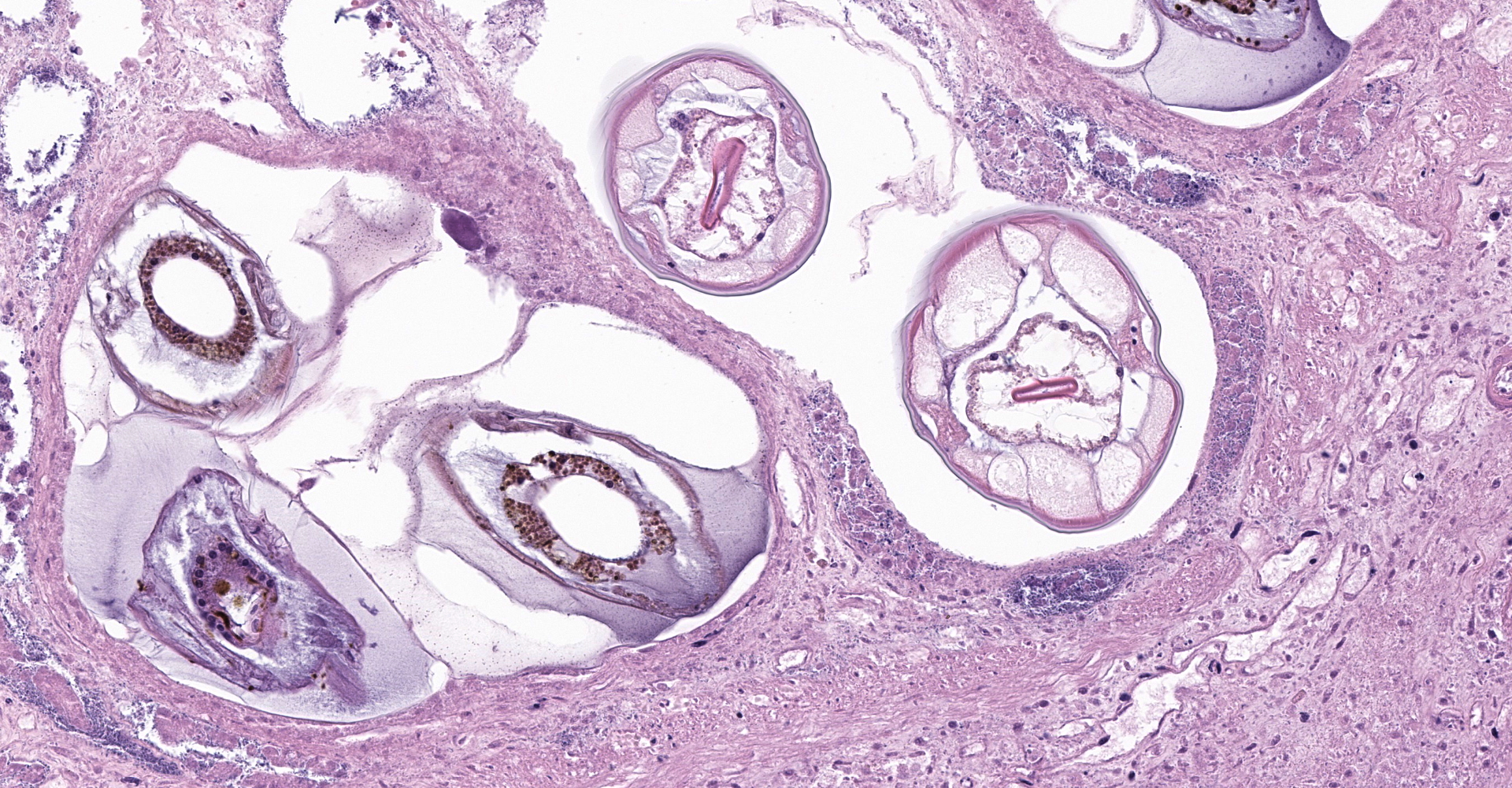

The overlying mucosa is multifocally elevated into wide polypoid folds. Diffusely the surface epithelium and multifocally the muscularis mucosa are effaced by necrotic material, with a few scattered remaining glands sometimes outlined by deeply basophilic granular material (mineralization). The mucosa is also diffusely infiltrated by numerous cavitated spaces containing 1-4 cross and longitudinal sections of larval nematode parasites. These larvae are ~200 um in diameter and up to 1.5 mm in length, have a thin to thick eosinophilic cuticle, platymyarian musculature, vacuolated lateral cords, and a large diameter intestine composed of a few multinucleated cells that occasionally contains brown iron pigment and are lined by a brush border. Rarely a muscular esophagus and part of a cuticularized buccal capsule are visible in longitudinal sections.

Similar, though less severe changes were found in the left ventral colon and the cecum (tissues not submitted). The colonic lymph node (tissue not submitted) showed moderate numbers of lymphoid follicles in the cortex and extending down into the medulla, as well as numerous degenerate and non-degenerate neutrophils and many macrophages occasionally exhibiting erythrophagocytosis expanding the subcapsular and medullary sinuses.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Right ventral colon: Severe necrosuppurative fibrinous colitis with submucosal edema, vascular thrombosis, and numerous intramucosal larval strongyles.

Contributor's comment:

The small strongyles of horses, also known as cyathostomins, are considered to be one of the most important pathogenic parasites in horses today. Over 40 species of cyasthostomins parasitize the cecum and colon of horses and individual hosts often are infected by 15 to 20 species at once during times of disease.1 Clinical disease is often negligible in cases with a few worms; however, when there is infection by large numbers of hypobiotic larvae significant disease sometimes leading to death can occur as a result of mass emergence.1,2 Emergence of larvae causes rupture of the muscularis mucosa and intense inflammation and edema.2 This clinical syndrome is most commonly observed during late fall, winter, or early spring.1 Clinical signs can be variable, but most commonly consist of persistent diarrhea, decreased levels of performance, ill thrift, edema, pyrexia, weight loss (sometimes to the point of emaciation), and colic.1,6 There is often a marked hypoalbuminemia with a neutrophilia, and hyperglobulinemia.1,4 Necropsy findings show inflammation of colon and/or cecum with mucosal hyperemia, hemorrhage, ulceration, or necrosis in the acute stages. More chronic cases sometimes only have mucosal thickening due to edema, and irregular areas of congestion.4 On close examination, there may be numerous mucosal nodules often only a few millimeters in diameter, which are raised red to black and can be umbilicated.2 The nodules within the cecum and colon within the submitted horse are much larger than commonly reported with cyathostomins, likely due to the intense inflammation and edema.

Cyathostomins have a direct life cycle. Eggs containing embryos in the morula stage of development are shed within the feces of an infected animal. Within the feces the egg hatches into the 1st larval stage (L1). The 1st and 2nd larval stages (L1 & L2) stay in the feces feeding on bacteria. The 3rd larval stage (L3), the infective stage, migrates from the feces into the soil and is ingested by a host. Next, larva migrate and develop in the deep mucosa or submucosa of large intestines (mainly cecum and ventral colon). L3 larvae can remain within the intestinal wall for periods ranging from about 4 months to as long as 2 years.4 Finally, they emerge to the lumen to develop into adults. Adults are mainly found in the dorsal and ventral colon and tend to cause few clinical problems.1 New eggs may be passed in the feces onto the pasture within 5-6 weeks.4

There is debate about the significance of increased resistance to anthelmintics causing increased cases of cyathostominosis. Currently, there is widespread resistance to benzimidazoles, and to a lesser extent pyrantel, as well as an emerging resistance to macrocyclic lactones.6 Anthelmintic treatment and specific husbandry were not reported in this case.

In the sections examined, there are large numbers of short and long bacilli bacteria that infiltrate the mucosa and submucosa. Given the extensive damage and inflammation within the intestinal wall, these may be opportunistic gastrointestinal flora causing a secondary bacterial infection or they may represent postmortem overgrowth given the 2 day postmortem interval.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathobiological Sciences

University of Wisconsin-Madison

School of Veterinary Medicine

2015 Linden Drive West

Madison, WI 53706

JPC diagnosis:

1. Colon: Colitis, necrosuppurative, multifocal to coalescing, with Peyer's patch necrosis, necrotizing vasculitis, fibrin thrombi, and severe submucosal edema.

2. Colon, mucosa: Cyathostome larvae, numerous.

3. Mesenteric and serosal arteries: Intimal bodies, multiple.

JPC comment:

The contributor provides a good review of cyathostomins in the horse. In addition to the horse, different species within the Cyathostominae subfamily parasitize the large intestine of elephants, pigs, marsupials, and turtles. While large strongyles may migrate beyond the mucosa of the cecum and colon, cyathostomin do not.3 A heavy cyathostomin larval burden, along with tapeworms, has been associated with cecocolic intussusception.5

As stated by the contributor, a number of anthelminthics are no longer effective against cyathostomin, such as phenothiazine, thiabendazole, cambendazole, mebendazole, fenbendazole, oxfendazole, and febantel. There are rare reports of treatment success by combining anthelminthic treatment with corticosteroids to target inflammation.3

Intimal bodies occur primarily in the small arteries and arterioles of horses, most often in the brain, placenta, and submucosa of the intestine. All age horses are affected and arise from degeneration and mineralization of subendothelial smooth muscle cells and intercellular material. They are considered a background lesion and have no functional significance.7

Small cyathostomes rarely cause this severity of pathology, and there are extensive areas of inflammation not centered on larvae. We speculate that a component of the colitis may be due to pathogenic bacteria, such as Clostridium spp or Salmonella spp. The reported clinical history of colic and diarrhea may support an acute insult on top of the cyathostome burden. A culture of the gastrointestinal contents may have provided additional information in this case. This horse was also administered flunixin meglumine (Banamine) non-steroidal anti-inflammatory therapy. This section of tissue is from the right ventral colon, but NSAID injuries may present in locations other than the right dorsal colon.

References:

1. Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML, Alcaraz, A In: Bowman DD, ed. Georgis' Parasitology for Veterinarians. 8th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2003:158-159, 177-178.

2. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:248-9.

3. Coles TB, Eberhard ML, Lightowlers MW, Lynn RC, Little SE. Family Strongylidae; Subfamily Cyathostominae. In: Bowman DD, ed. Georgis' Parasitology for Veterinarians, 10th Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2014:175-176.

4. Corning S. Equine cyathostomins: a review of biology, clinical significance and therapy. Parasit Vectors. 2009;2 (Suppl 2): S1.

5. Marshall JF, Blikslager AT. Surgical Disorders of the Large Intestine. In: Smith BP, ed. Large Animal Internal Medicine, 5th Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2015:719.

6. Peregrine AS, Molento MB, Kaplan RM, Nielsen, MK. Anthelmintic resistance in important parasites of horses: does it really matter?. Vet Parasitol. 2014;201(1-2):1-8.

7. Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, Vol 3, 6th Ed. St. Louis, MO:Elsevier. 2016:61.