Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Hepatocutaneous

syndrome has been reported in humans, dogs, cats, and the black rhinoceros.1,2,5-7

Older small breed dogs are primarily affected. The long-term prognosis for

animals with hepatocutaneous syndrome is very poor. In cases of hepatocutaneous

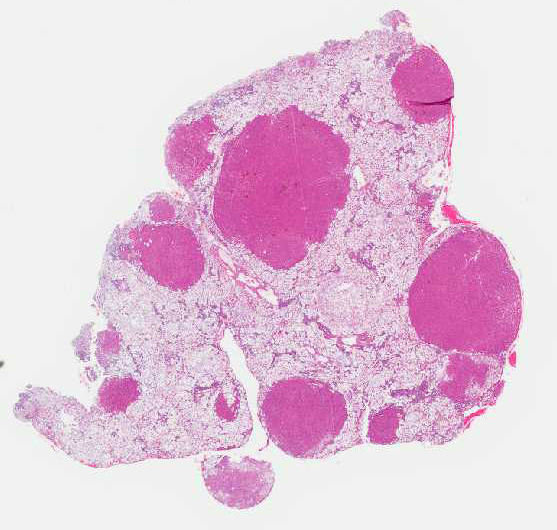

syndrome, the liver has a gross appearance resembling cirrhosis.

Histologically, there are foci of regenerative nodular hyperplasia separated by

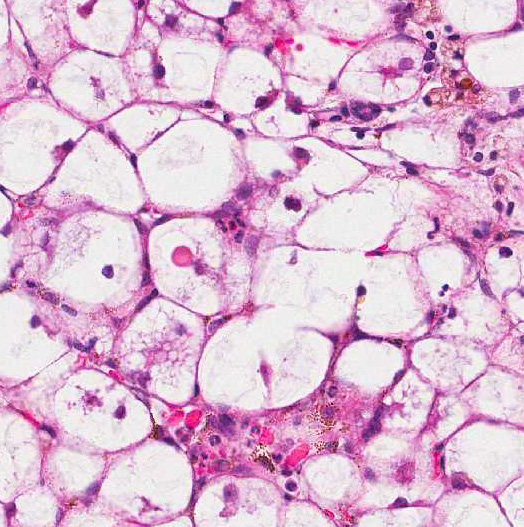

areas of parenchymal collapse ![]() containing heavily vacuolated

hepatocytes. Hepatic changes are considered idiopathic, but have been suggested

to be due to an underlying metabolic, hormonal, or toxic etiology. The

pathogenesis of the associated skin lesions is unknown, but hepatic dysfunction

with derangement of glucose and amino acid metabolism have been suggested.1,2,7

containing heavily vacuolated

hepatocytes. Hepatic changes are considered idiopathic, but have been suggested

to be due to an underlying metabolic, hormonal, or toxic etiology. The

pathogenesis of the associated skin lesions is unknown, but hepatic dysfunction

with derangement of glucose and amino acid metabolism have been suggested.1,2,7

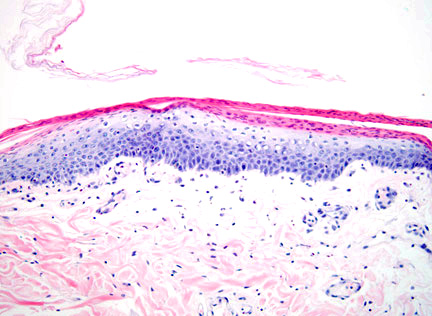

This disorder produces characteristic cutaneous changes that typically occur on the footpads, mucocutaneous junctions, and pressure points. Gross changes may include crusting, erosion/ulceration, erythema, alopecia, and exudation. The histologic appearance is often referred to as red, white and blue. (The red corresponds to superficial parakeratotic hyperkeratosis; white corresponds to pallor in the stratum spinosum which is due to intracellular edema; blue corresponds to basal cell hyperplasia.2 Depending on the duration of the disease, all of the classical components of the histologic lesion may or may not be seen and could also be obscured by secondary changes (e.g. erosion, ulceration, infection). Superficial necrolytic dermatitis (SNE), necrolytic migratory erythema (NME), and metabolic epidermal necrosis (MEN) have been terms used to refer to the cutaneous syndrome in humans.1 The majority of canine cases are associated with liver disease, whereas human cases are typically associated with a functional pancreatic glucagonomas. However, in animals, the cutaneous lesions have also been associated with glucagon secreting tumors, diabetes mellitus, pancreatic carcinoma, gastric carcinoma and thymic amyloidosis.5,7

Other differential diagnoses to consider for parakeratotic skin diseases include zinc-responsive dermatosis, generic dog food dermatosis, lethal acrodermatitis of bull terriers, irritant contact dermatitis, and thallium toxicosis.1,2 The signalment, clinical history, and ancillary diagnostic tests, in combination with histologic findings, should easily differentiate between these potential differentials.

Conference Comment:

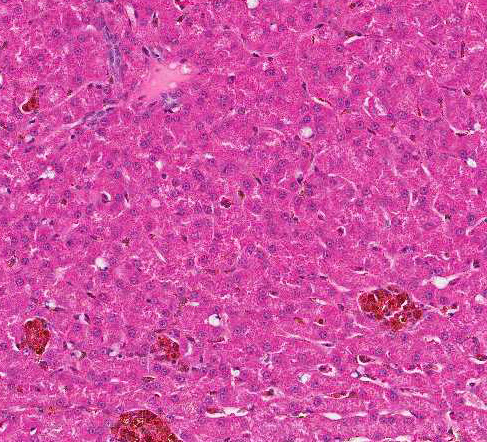

The moderator commented that this syndrome is very difficult to diagnose correctly based solely on the histologic hepatic lesions. The conference histologic description was very similar to the contributors description above. There is a sharp line of demarcation between de-generative and regenerative areas; sinusoids are compressed and largely obscured in the areas of vacuolar degeneration. Low numbers of binucleate hepatocytes, as well as rare mitoses within the foci of hepatocellular regeneration.

The moderator commented on the atypical appearance of the regenerative nodules, noting that in regeneration, hepatic cords are most often arranged in double rows, while in this case they are singly arranged. The presence of one portal area per regenerative nodule is typical and is seen in some of the regenerative foci in this case. Conference participants also commented on the relative absence of fibrosis in the H&E stained section. The excellent gross image provided by the contributor was also discussed and the moderator noted that the gross cluster of grapes appearance imparted by the regenerative nodules is classic for this condition.

Similar cutaneous lesions may be seen (without liver lesions), with glucagon-secreting pancreatic tumors. There is also a single case report of superficial necrolytic dermatitis associated with an insulin producing tumor in a dog.4

References:

1. Byrne KP. Metabolic epidermal necrosis-hepatocutaneous syndrome. Vet Clin

North Am Sm Anim Pract. 1999; 29(6):1337-1355.

2. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK. Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat.

2nd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing Professional; 2005:86-91.

3. Hall-Fonte DL, Center SA, McDonough SP, Peters-Kennedy J et al. Hepatocutaneous syndrome in Shih Tzus: 31 cases (1996-2014). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2016; 248(7):802-813.

4. Isidoro-Ayza M, Lloret A, Bardagi M, Ferrer L, Martinez J. Superficial necrolytic dermatitis in a dog with an insulin-producing pancreatic islet cell carcinoma. Vet Pathol. 2014; 51(4):805-808.

5. Kimmel SE, Christiansen W, Byrne KP. Clinicopathological, ultrasonographic,

and histopathological findings of superficial necrolytic dermatitis with hepatopathy in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2003; 39:23-27.

6. Munson L, Koehler JW, Wilkinson JE, Miller RE. Vesicular and ulcerative

dermatopathy resembling superficial necrolytic dermatitis in captive black

rhinoceroses (Diceros bicornis). Vet Pathol. 1998; 35:31-42.

7. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:332.