Signalment:

Gross Description:

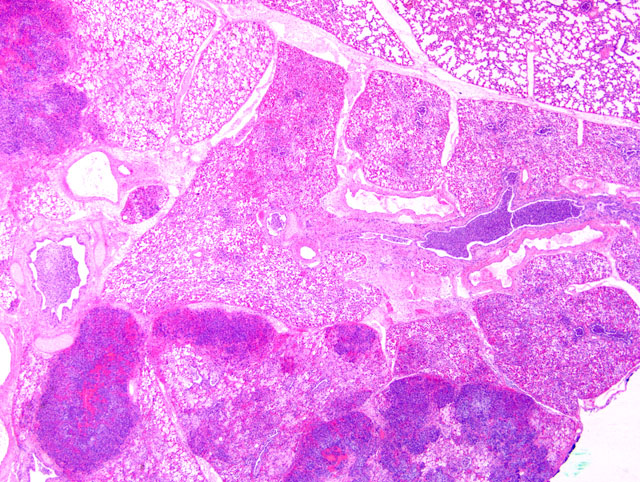

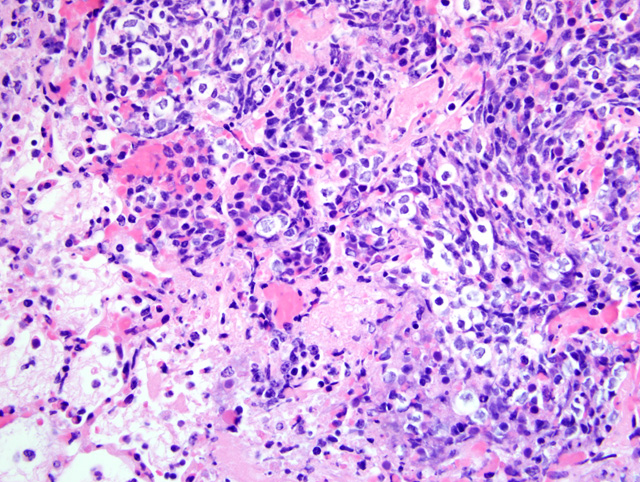

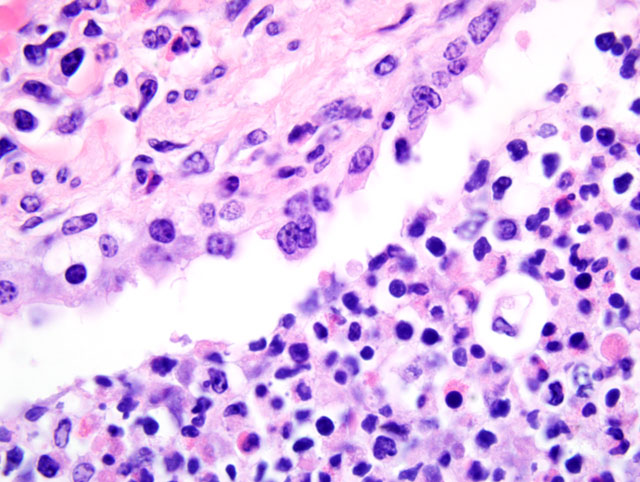

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The bronchopneumonia in the two Holstein calves reported here was similar to pneumonia described with M. haemolytica infection in that there was significant leukocyte necrosis as evidenced by oat cells, widespread accumulation of edema fluid, neutrophils, macrophages, fibrin, foci of hemorrhage and bacterial aggregates within alveolar spaces and airway lumina and interlobular septae were distended with serofibrinous exudate.(3) A similar lesion to M. haemolytica would be anticipated as it has been shown that M. granulomatis has leukotoxin activity in vitro.(2,7) However, large areas of coagulation necrosis surrounded by a thick rim of leukocytes, as is frequently observed with M. haemolytica pneumonia (3), were lacking in the M. granulomatis lesion. These observations suggest that, although both M. granulomatis and M. haemolytica share virulence factors (2,7), there may be subtle differences in pathological expression. However, more cases of M. granulomatis pneumonia would need to be examined before any conclusions could be drawn with regard to expression of virulence.Â

These calves also had focal infection with BRSV which was confirmed by PCR and immunohistochemistry. Viral BRSV lesions were not present in all tissue sections submitted. Pulmonary BRSV infection likely predisposed these calves to bacterial pneumonia. While P. multocida and M. haemolytica are reported to be commensal in the bovine nasopharynx (3), it is unclear how these two calves became infected with M. granulomatis.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Leukotoxin, mentioned by the contributor, is an important virulence factor of M. haemolytica. A member of the repeats in toxin (RTX) family, leukotoxin is secreted during the log phase of growth, and its receptor is CD18.(3) At low concentrations, leukotoxin activates bovine platelets and leukocytes or induces their apoptosis (4), while at high concentrations it induces leukocyte lysis, resulting in the characteristic nuclear streaming noted microscopically in areas of necrosis.(3) Lipopolysaccharide, another important virulence factor, is synergistic with leukotoxin because it induces increased expression of β2-integrins on leukocytes which contain the CD18 receptor. Other important bacterial virulence factors include a polysaccharide capsule that assists in attachment and impairs phagocytosis, iron-regulated outer membrane proteins that bind transferrin and alter neutrophil function, adhesins that mediate attachment, and neuraminidase that decreases both respiratory mucus viscosity and repellant negative charge on host cells. Cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 are particularly important components of the complex inflammatory milieu produced in pneumonic mannheimiosis.(8)

Bovine parainfluenza virus 3, bovine herpesvirus 1, and BRSV all increase susceptibility to M. haemolytica, and presumably other respiratory pathogens, by infecting ciliated epithelium and reducing mucociliary clearance; the latter two also infect and impair alveolar macrophages. Of note, bovine herpesvirus 1 is also thought to increase susceptibility to the effects of M. haemolytica by upregulating CD18 expression in neutrophils.(3)

As mentioned by the contributor, there is some slide variation with respect to the presence of viral syncytia. In a few sections, participants noted viral syncytia in bronchioles with multifocal bronchiolar epithelial necrosis, consistent with bronchointerstitial pneumonia due to BRSV infection. Additionally, lymphatic vessel lumina within interlobular septa are multifocally occluded by coagula of fibrin and mixed inflammatory cells. There are rare intravascular megakaryocytes in some sections, which participants speculated may be associated with terminal bone marrow hypoxia. Intravascular megakaryocytes in the human lung were first described in 1893, and it has since been demonstrated that under normal conditions, intact megakaryocytes leave the bone marrow and reach the pulmonary capillary bed, where they release platelets by fragmentation of their cytoplasm.(9)

References:

2. Bojesen AM, Larsen J, Pedersen AG, Morner T, Mattson R, Bisgaard M: Identification of a novel Mannheimia granulomatis lineage from lesions in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). J Wildl Dis 43:345-352, 2007

3. Caswell JL, Williams KJ: Respiratory system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 601-605. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

4. Cudd LA, Ownby CL, Clarke CR, Sun Y, Clinkenbeard KD: Effects of Mannheimia haemolytica leukotoxin on apoptosis and oncosis of bovine neutrophils. Am J Vet Res 62:136-140, 2001

5. Devriese LA, Bisgaard M, Hommez J, Uyttebroek E, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F: Taxon 20 (Fam. Pasteurellaceae) in European brown hares (Lepus europaeus). J Wildl Dis 27:685-687, 1991

6. Riet-Correa F, Mendez MC, Schild AL, Ribeiro GA, Almeida SM: Bovine focal proliferative fibrogranulomatous panniculitis (lechiguana) associated with Pasteurella granulomatis. Vet Pathol 29:93-103, 1992

7. Veit HP, Wise DJ, Carter GR, Chengappa MM: Toxin production by Pasteurella granulomatis. Ann NY Acad Sci 849:479-484, 1998

8. Wollums AR, Ames TR, Baker JC: The bronchopneumonias (respiratory disease complex of cattle, sheep, and goats). In: Large Animal Internal Medicine, ed. Smith BP, 4th ed., pp. 613-617. Mosby Elsevier, St. Louis, MO 2009

9. Zucker-Franklin D, Philipp CS: Platelet production in the pulmonary capillary bed: new ultrastructural evidence for an old concept. Am J Pathol 157:69-74, 2000