Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 19, Case 2

Signalment:

5-year-old, male, Bearded Dragon (Pogona vitticeps).

History:

Three-day history of anorexia, no defecation, and dull mentation. On physical exam: poor body condition score, severe dehydration, and palpable mass in the mid-left coelomic cavity, described as mobile, firm, and approximately 2 x 4 cm in size. No further diagnostics performed. Euthanasia was elected due to declining condition.

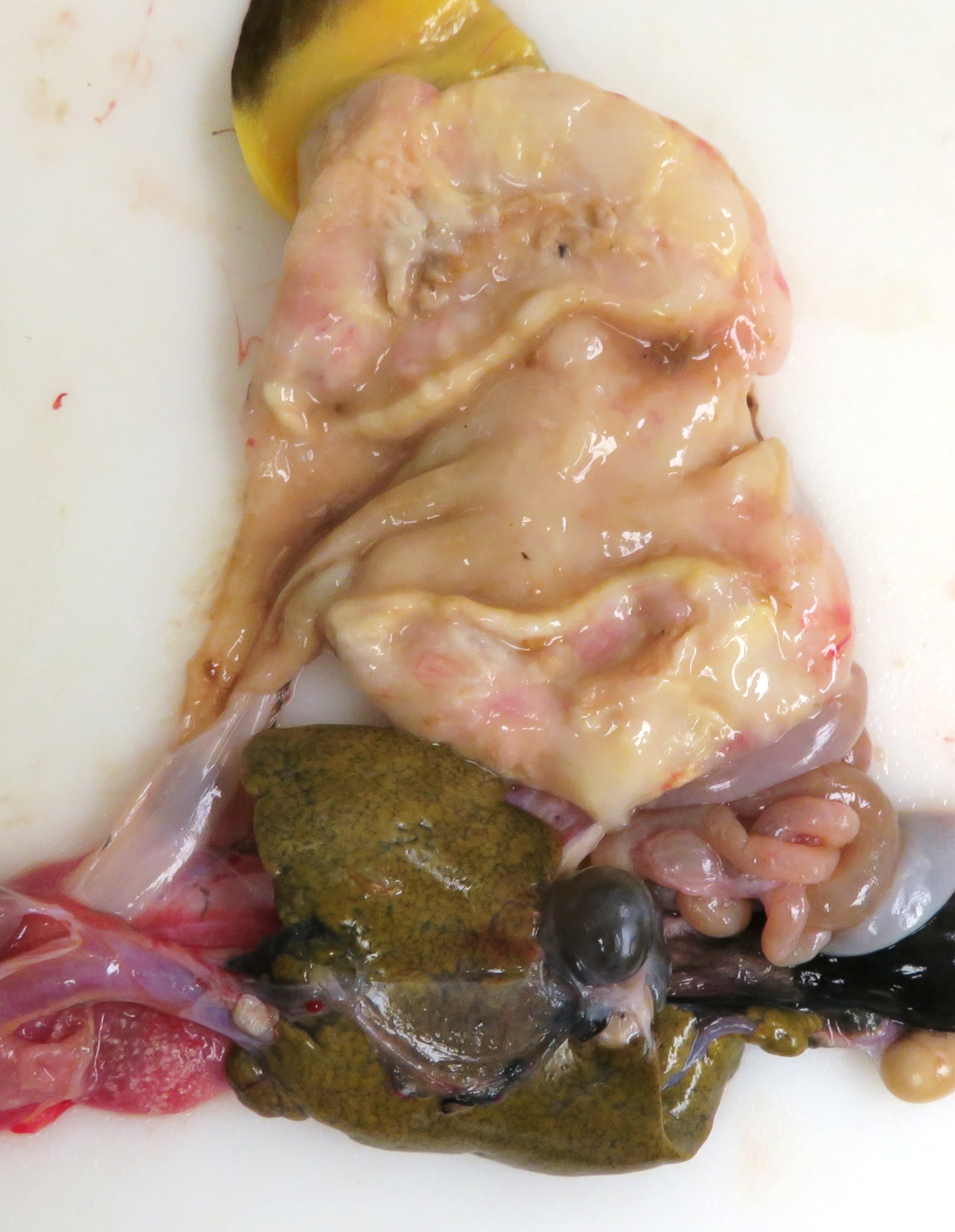

Gross Pathology:

The animal had moderate body fat stores and decreased muscle mass. The mucous membranes of the mouth were pale, and the tongue was pale yellow. The serosal surface of the stomach had multifocal, confluent, white-tan, firm, variably demarcated nodules, which extended to the adjacent fat pad, mesentery, and small intestine. On cut section, the gastric wall was diffusely thickened, white-tan, and firm.

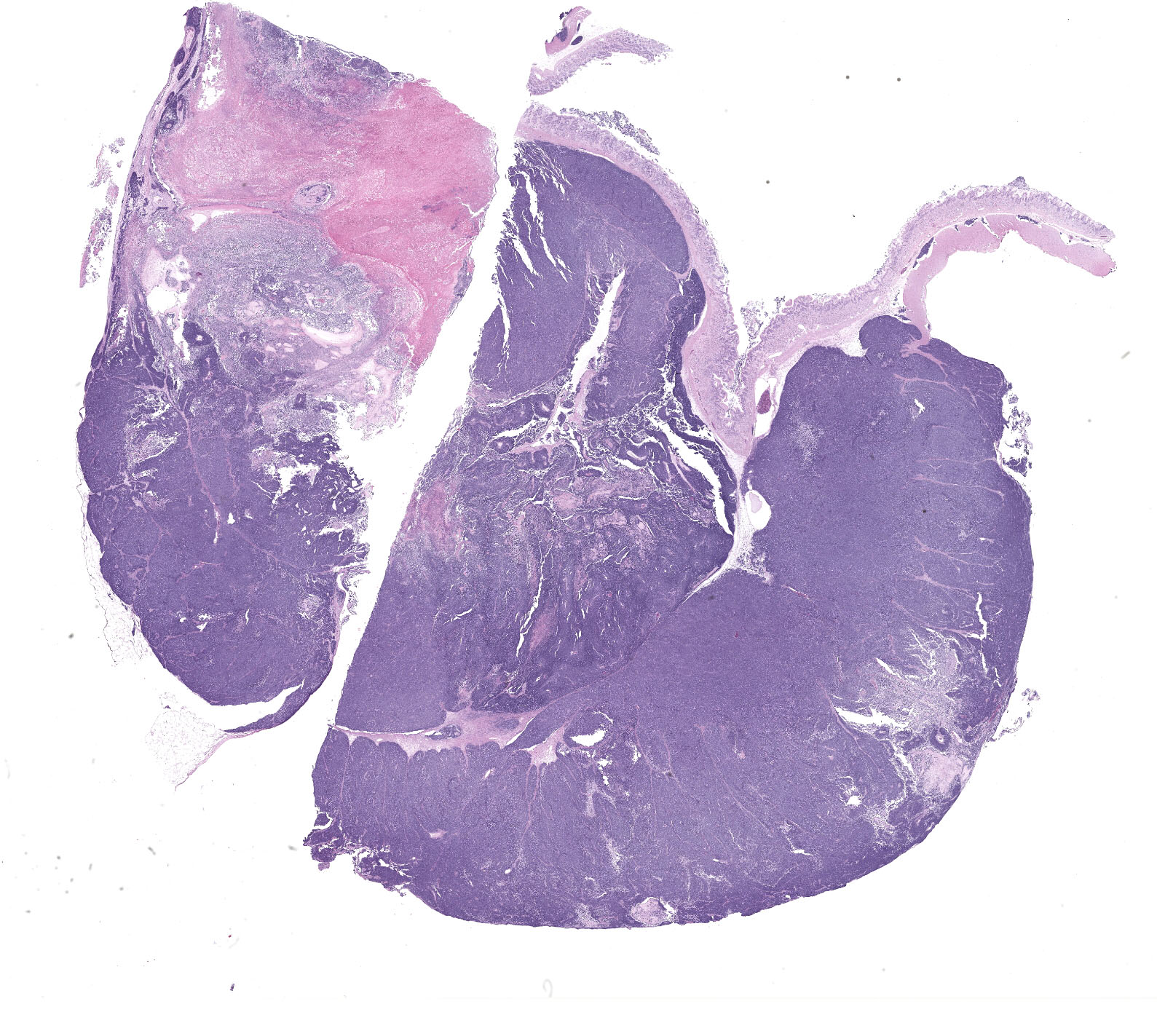

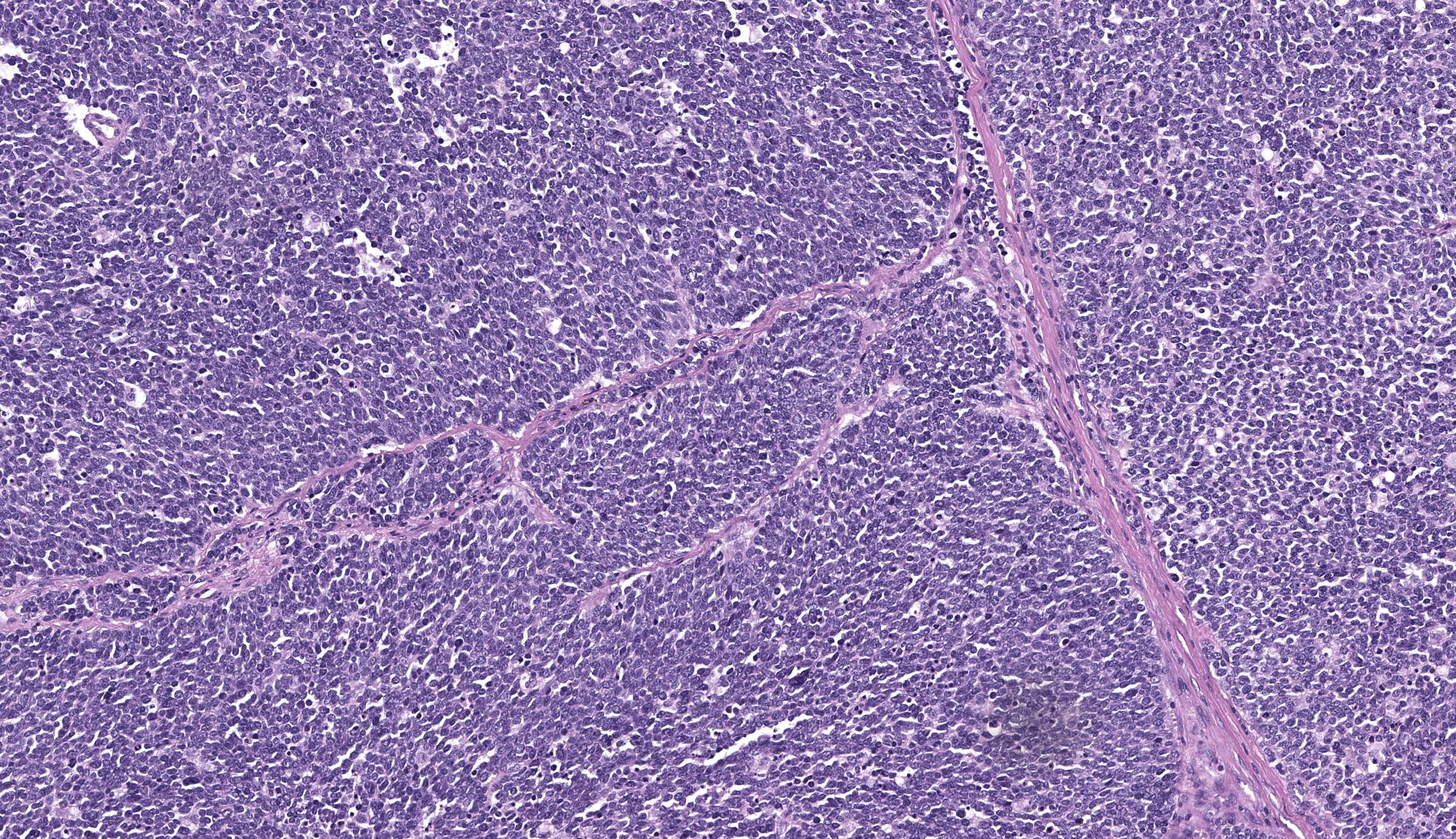

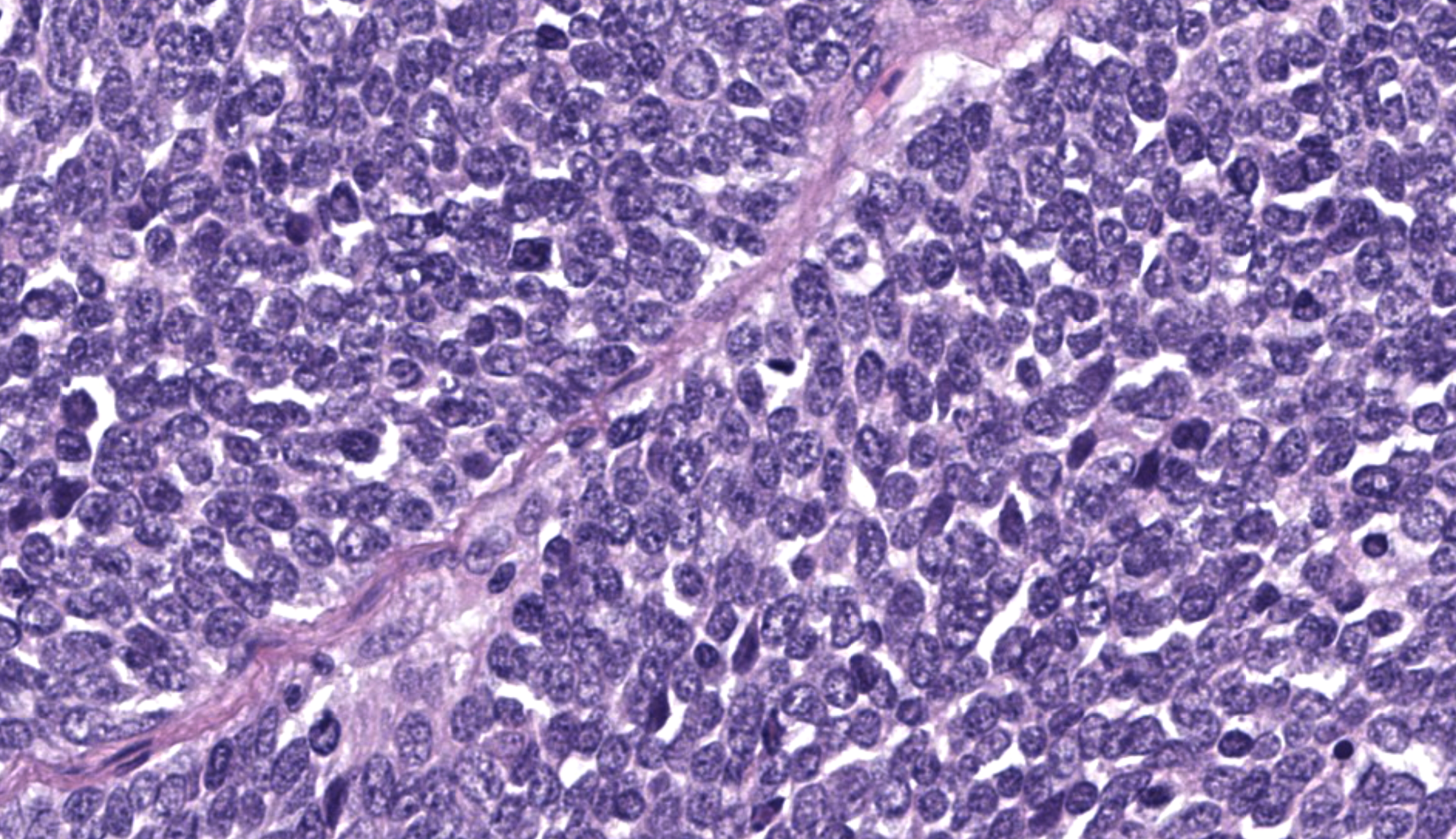

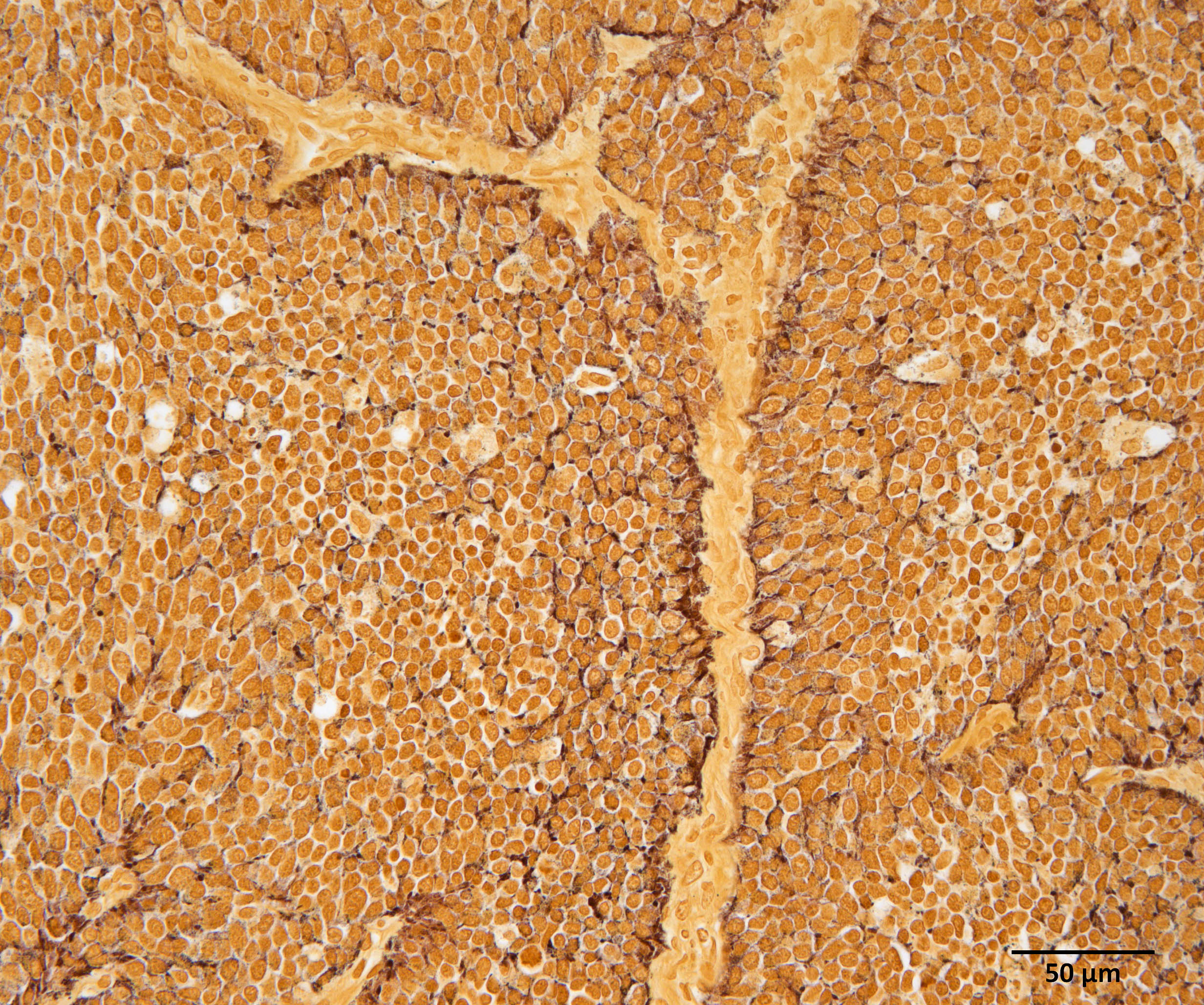

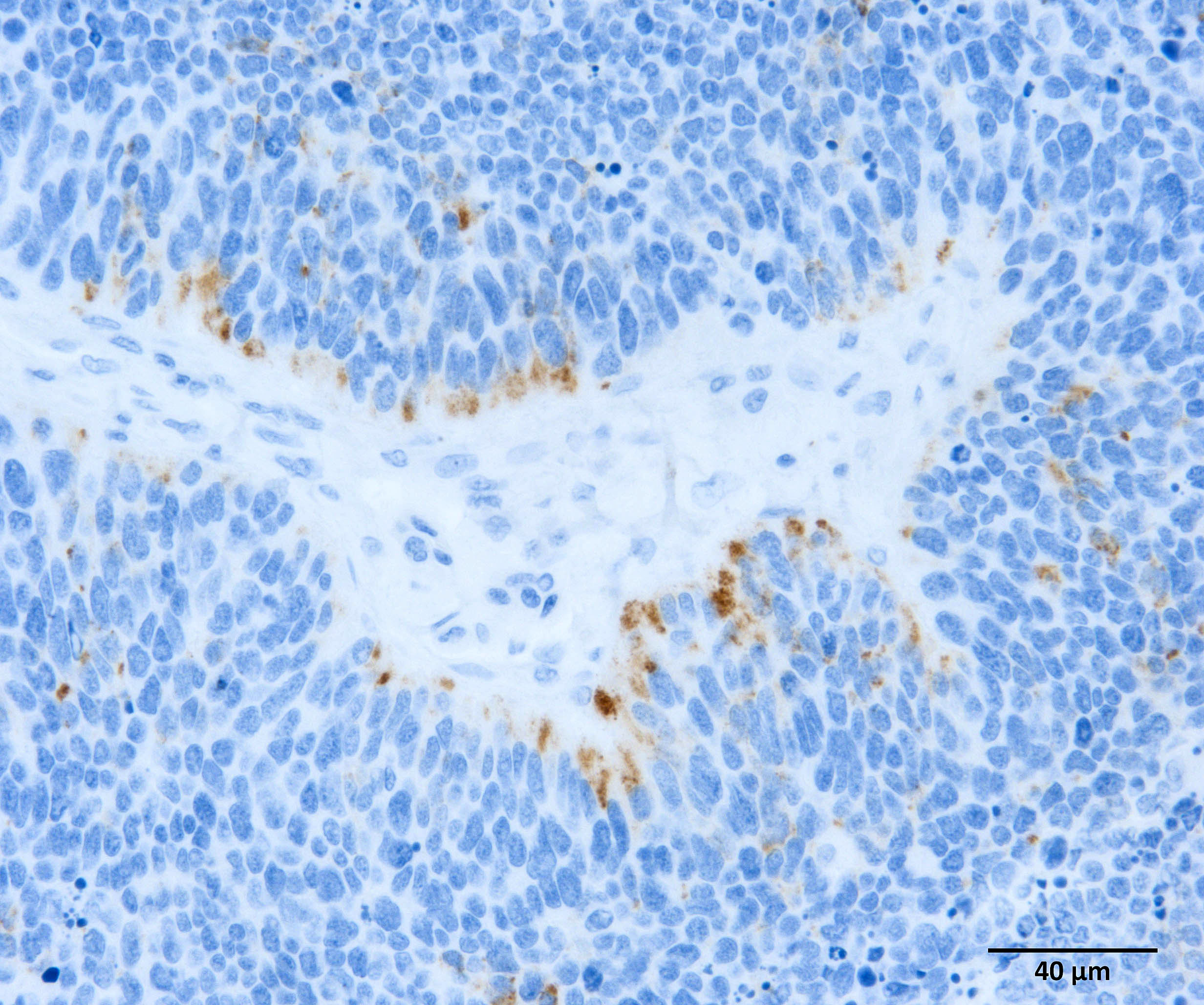

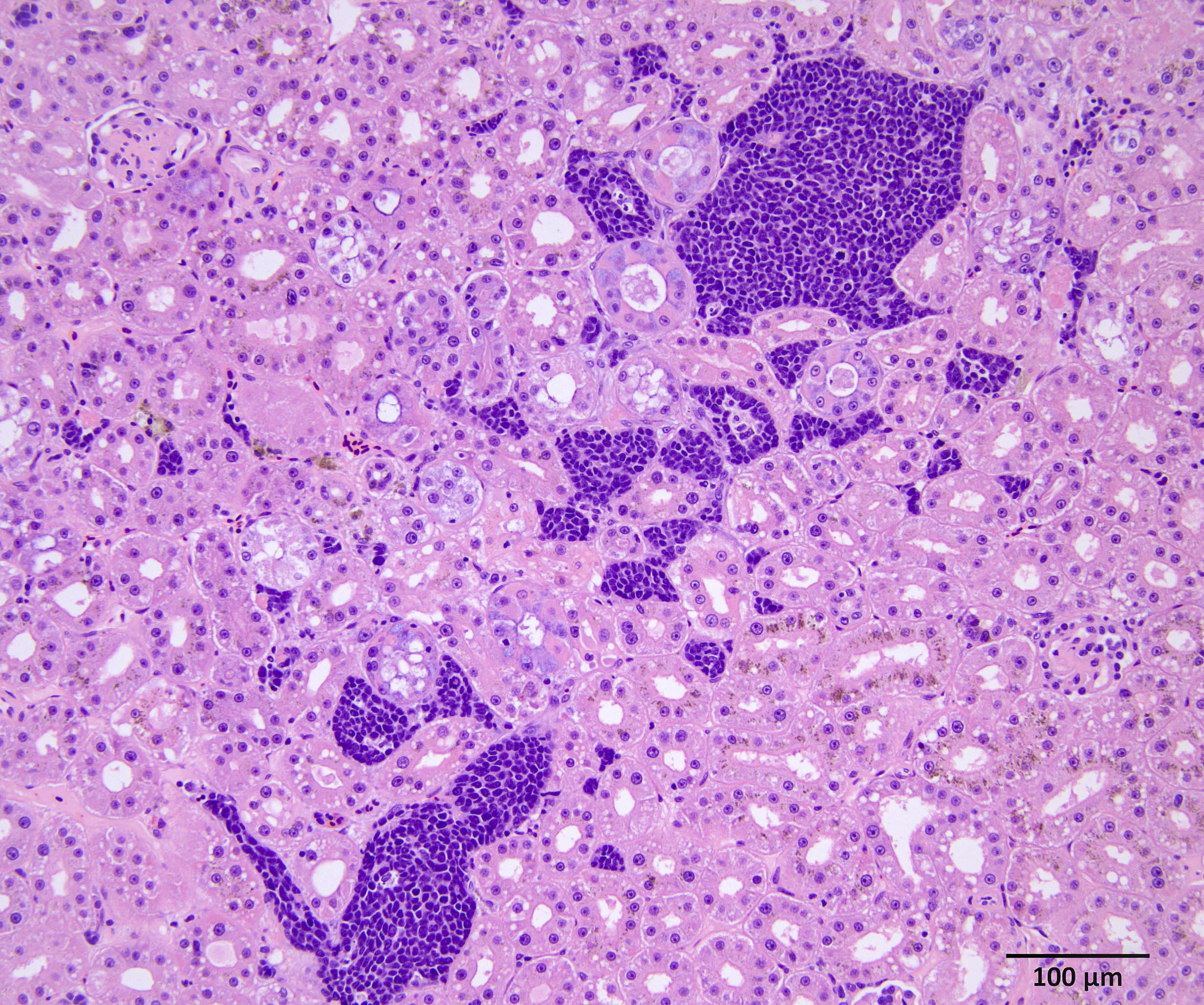

Microscopic Description:

Gastric tumor: Expanding and effacing the gastric submucosa, tunica muscularis, and serosa, there is a well-demarcated, unencapsulated, multi-lobular, infiltrative, and densely cellular neoplasm. The growth is composed of neoplastic polygonal cells arranged in packets, sheets, and occasional pseudorosettes with nuclear palisading around blood vessels, all supported by a delicate fibrovascular stroma. The neoplastic cells have scant, poorly defined, amphophilic, finely granular cytoplasm; their nuclei are round to oval with finely stippled chromatin, and small to inconspicuous nucleoli. There is mild to moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. A total of 37 mitotic figures (sometimes atypical) are counted in 10 consecutive HPF (x400). Many lymphatic vessels are occluded by neoplastic cells. There are multifocal areas of necrosis characterized by eosinophilic cellular and basophilic karyorrhectic debris and eosinophilic smooth to slightly fibrillar deposits (fibrin); sometimes intermixed with colonies of coccobacilli. There are numerous apoptotic cells and variably sized aggregates of granulocytes, lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells within the mass. The gastric mucosal epithelium and glands are usually spared. Approximately 10% of the neoplastic cells have argyrophilic cytoplasmic granules (confirmed with Grimelius stain).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for somatostatin on section of gastric tumor: cytoplasmic immunoreactivity in approximately 10% of neoplastic cells.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma (suspected malignant somatostatinoma)

Contributor’s Comment:

Neuroendocrine (NE) tumors (also called carcinoids) of the alimentary tract arise from dispersed enteroendocrine cells.5 There are many types of enteroendocrine cells which have differences in anatomic location and hormonal mediator produced (e.g. G cells are located in the pylorus and produce gastrin), and NE tumors can be further subclassified based on these properties. NE tumors may be benign or malignant, well-differentiated or poorly differentiated, functional or non-functional, and exhibit single or multi-hormonal expression of secretory mediators.5,9

Gastric neuroendocrine carcinomas are a highly malignant emerging entity in young bearded dragons, and are frequently metastasized to the liver upon presentation.9,4,7,11 Commonly observed clinical signs include anorexia, vomiting, weight loss, and lethargy.4,7,9,11 Reported clinical pathologic abnormalities include hyperglycemia and anemia.7,9,11 Grossly, gastric tumors are described as variable in size, multinodular but often well demarcated, pale tan to white, firm, with protrusion into the gastric lumen and ulceration of the associated gastric mucosa.9 Occasional cases report no masses identified grossly.9 Histopathology of these tumors are characteristic of neuroendocrine neoplasms, and they are primarily located in the gastric submucosa.4,7,9,11 In one publication, extended IHC analysis of five cases revealed consistent immunoreactivity for somatostatin (n=5), along with varying immunoreactivity for gastrin (n=3), synaptophysin (n=2), pancreatic polypeptide (n=2), chromogranins A and B (n=1), and glucagon (n=1); and therefore further characterized the neoplasms as malignant somatostatinomas.9

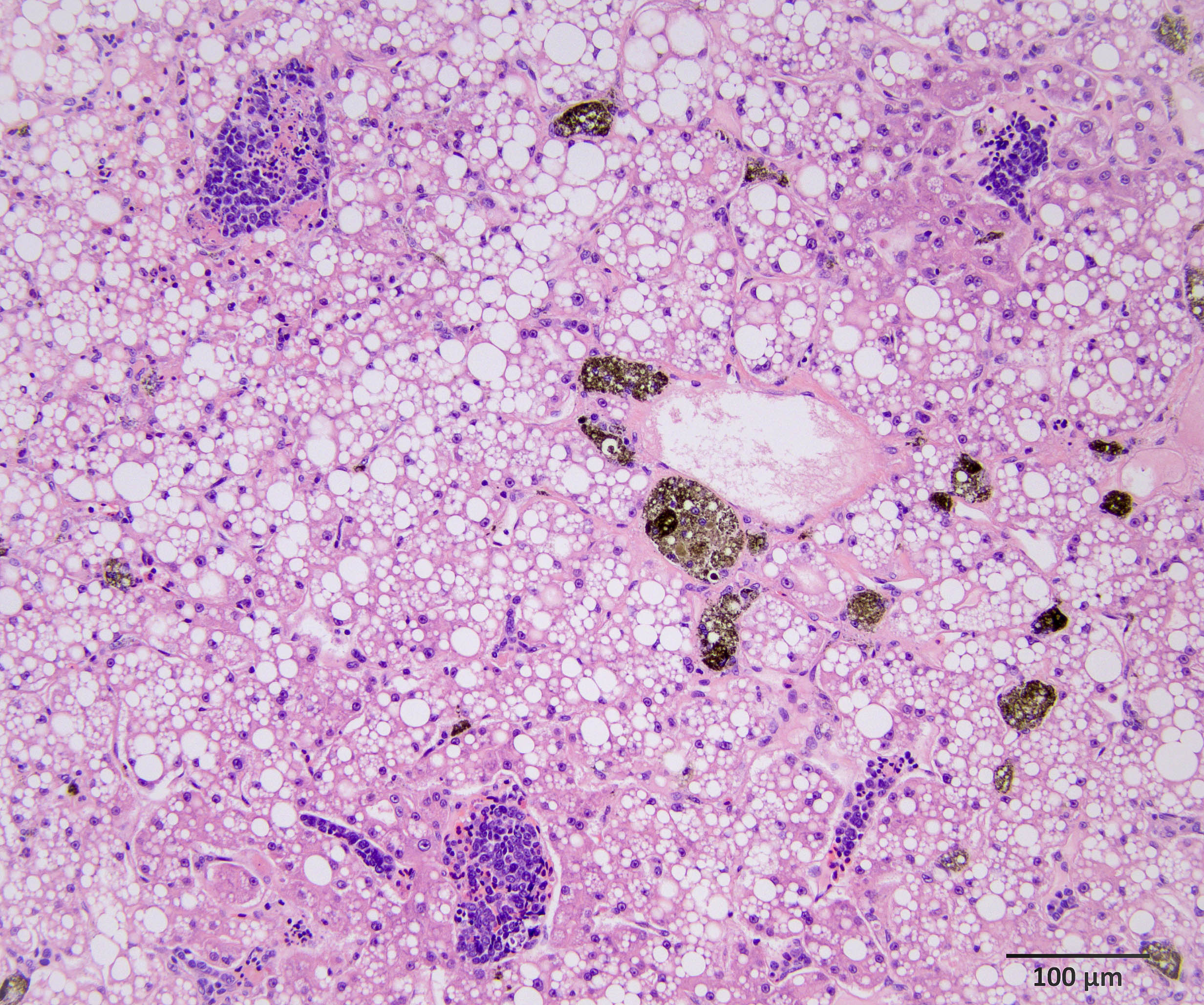

In our individual, there was widespread microscopic metastasis in the heart, lung, liver (with concurrent hepatic lipidosis), small intestine, kidney, adrenal gland, and testes. Cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for somatostatin was observed in a proportion of neoplastic cells and is similarly supportive of a more specific diagnosis of malignant somatostatinoma. However, IHC for other hormonal mediators was not pursued in our case, so the possibility of multi-hormonal expression was not assessed.

Hyperglycemia has been observed in some bearded dragons with these tumors9,7,11 and is also noted in a proportion of people with somatostatinomas.6 The pathogenesis of hyperglycemia is due to excessive production of somatostatin, which inhibits secretion of most pancreatic and gut hormones including insulin, leading to decreased glucose intake into cells and therefore elevation of glucose levels in the blood. In people, clinical disease due to excessive somatostatin production from NE tumors is called “somatostatin syndrome”, and is characterized by diabetes mellitus, cholelithiasis, and diarrhea/steatorrhea.6 It is possible that a similar syndrome is occurring in bearded dragons with gastric neuroendocrine carcinomas, however further investigation is needed.

In terms of comparative pathology, gastric NE tumors have been rarely reported in the dog,3,5,8 cat,5,10 and ferret.1 In addition, there is a published case series of benign gastric NE tumors in three captive snow leopards.2

Contributing Institution:

Western College of Veterinary Medicine

University of Saskatchewan

52 Campus Dr, Saskatoon, SK, Canada S7N 5B4

https://wcvm.usask.ca/departments/vet-pathology.php

JPC Diagnosis:

Stomach: Neuroendocrine carcinoma

JPC Comment:

Case 2 is a classic neuroendocrine neoplasm in a bearded dragon. We attempted to characterize it further, although the JPC’s IHCs (aside from a weakly reactive chromogranin) were negative or non-contributory. Dr. Peiffer emphasized the need for an antibody-specific control in addition to a species tissue control in evaluating the performance of assays that have not been validated in a particular species. This is a frequent consideration for us given that we share laboratory services with a larger human hospital, and few of our antibodies have been validated for exotic species. The Grimelius stain employed by the contributor is a creative way to assess for neuroendocrine cells producing CCK or somatostatin as these characteristically lack an argyrophil reaction.12 That stated, it is difficult to interpret this stain without a matched control to assess stain performance. Finally, conference participants discussed the somatostatin IHC result – we considered whether the lower proportion of immunoreactive cells could reflect a different neuroendocrine neoplasm producing multiple hormones. For this reason, we settled on a neuroendocrine carcinoma as the most appropriate morphologic diagnosis for this case.

The gross images from this case are excellent and merit a short sidebar discussion. Recognizing normal anatomy is critical when interpreting lesions in zoo animals and wildlife. As the liver of reptiles contains melanomacrophages, the darkened color of the liver in this case is normal and is perhaps accentuated by the histologic finding of lipidosis reported by the contributor. Melanomacrophages are pigment-laden macrophages that contain melanin granules, though they may also contain hemosiderin and/or lipofuscin which cannot be distinguished on H&E alone. Melanomacrophages are also present in fish and amphibians. Melanomacrophage hyperplasia is a non-specific feature that can be appreciated microscopically and in some cases, grossly. Conference participants also discussed the abdominal fat pads and far caudal position of the kidneys in this species (not visible in the provided photo, unfortunately).

References:

- Bousquet T, Bravo-Araya M, Davies JL. Gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma (carcinoid) in a ferret (Mustela putorius furo). Can Vet J. 2022;63(11):1109-1113.

- Dobson EC, Naydan DK, Raphael BL et al. Benign gastric neuroendocrine tumors in three snow leopards (Panthera uncia). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2013;44(2):441-446.

- Herbach N, Unterer S, Hermanns W. Gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma in a dog. Open J Pathol. 2012;2:162-165.

- Lyons JA, Newman SJ, Greenacre CB et al. A gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma expressing somatostatin in a bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). J Vet Diagn Invest. 2010;22:316-320.

- Munday JS, Löhr CV, Kiupel M. Tumors of the alimentary tract. In: Meuten DJ, 5th edition. Tumors in domestic animals. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2017:559.

- Nesi G, Marcucci T, Rubio CA et al. Somatostatinoma: clinico-pathological features of three cases and literature reviewed. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(4):521-526.

- Perpiñán D, Addante K, Driskell E. Gastrointestinal disturbances in a bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). J Herpetol Med Surg. 2010;20(2-3):54-57.

- Ovigstad G, Kolbjørnsen Ø, Skancke E et al. Gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma associated with atrophic gastritis in the norwegian lundehund. J Comp Pathol. 2008;139(4):194-201.

- Ritter JM, Garner MM, JA Chilton et al. Gastric neuroendocrine carcinomas in bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). Vet Pathol. 2009;46:1109-1116.

- Rossmeisl JH Jr, Forrester SD, Robertson JL et al. Chronic vomiting associated with a gastric carcinoid in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2002;38(1):61-66.

- Thebeau JM, Martinson SA, Clancey NP et al. Pathology in practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2022;259(S2):1-4.

- Grimelius L. Methods in neuroendocrine histopathology, a methodological overview. Ups J Med Sci. 2008;113(3):243-60.