CASE II: SP-18-1795 (JPC 4117534)

Signalment:

4-year-old female marine toad (Rhinella marina)

History:

The toad had a coelomic mass of unknown duration.

Gross Pathology:

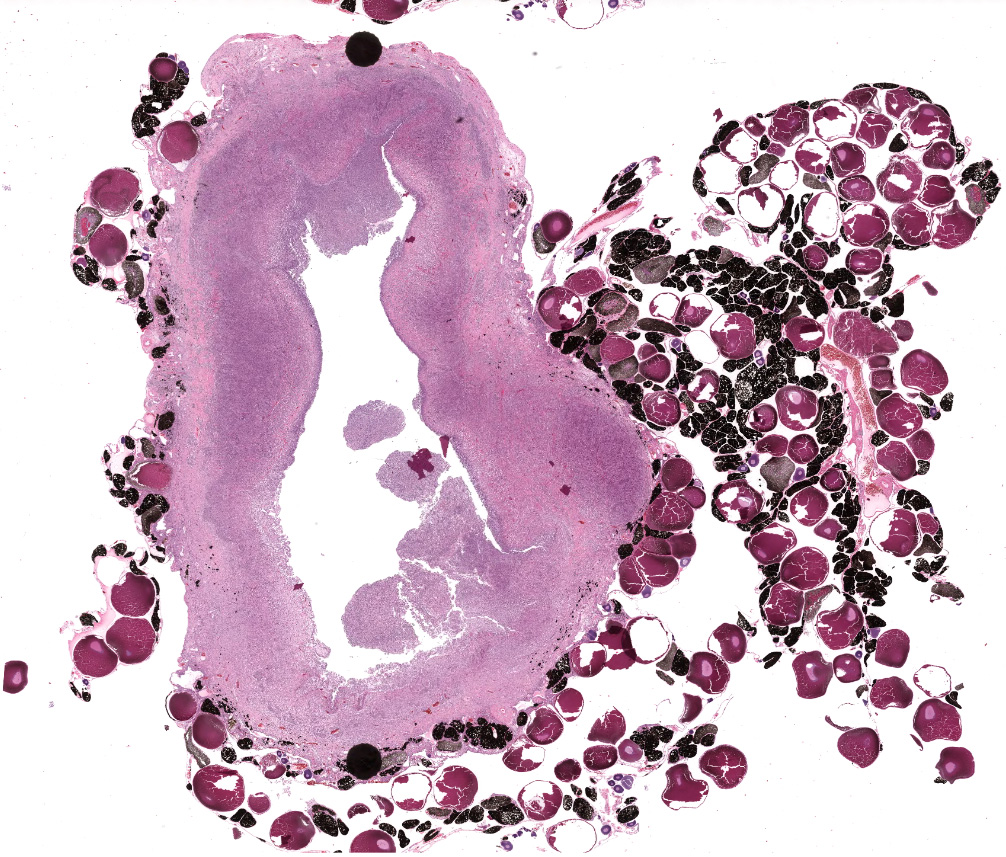

This toad had an approximately 3 cm encapsulated mass present on the left ovary, as well as a 1.5 cm subcutaneous mass.

Laboratory Results:

Numerous Brucella spp. were isolated from the ovarian mass. Brucella isolates were identified to the genus level using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Partial 16s rDNA sequencing was performed and confirmed a Brucella inopinata- like spp.

Microscopic Description:

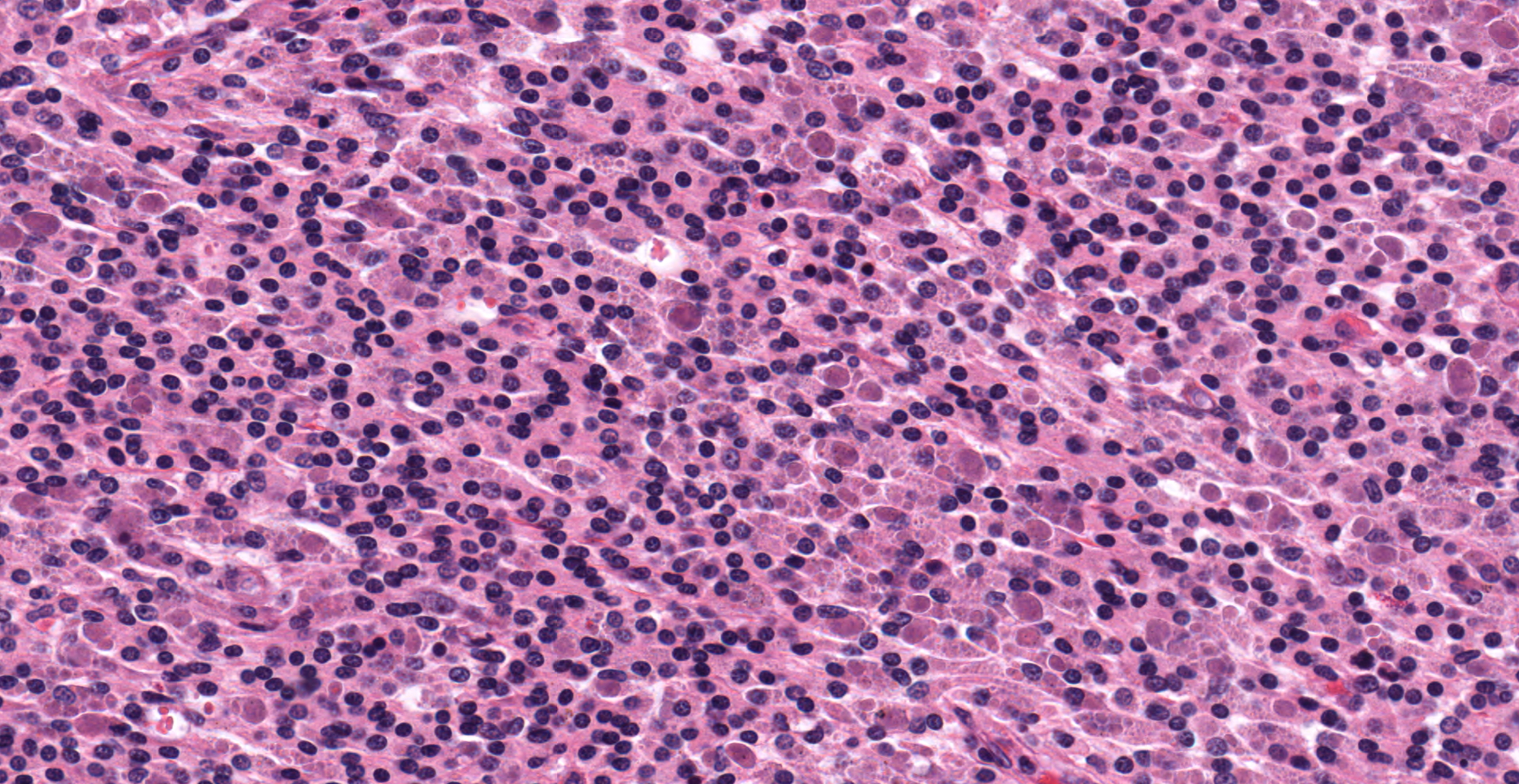

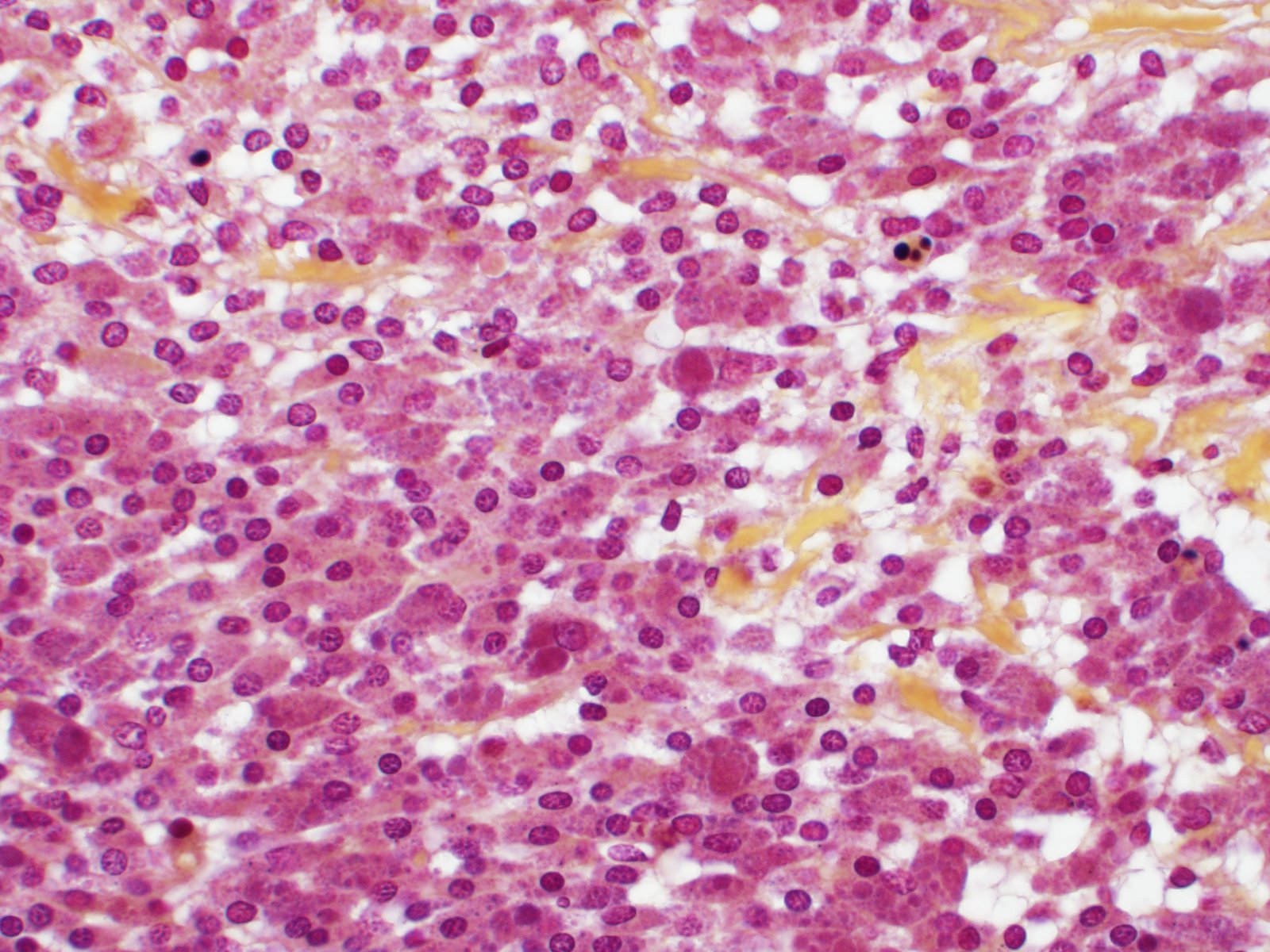

Effacing the normal ovarian architecture and compressing normal ova is a large mass primarily composed of sheets of histiocytes mixed with scattered lymphocytes and heterophils. There are multifocal to coalescing areas of necrosis characterized by degenerate cells with pyknotic nuclei and eosinophilic and karyorrhectic cellular debris. Contained within the cytoplasm of histiocytes and often freely within necrotic foci are numerous Gram negative 1-2 um diameter small bacilli. Surrounding necrotic areas are large numbers of reactive fibroblasts and epithelial macrophages interspersed by bands of collagen. The ovary contains abundant multifocal melanin pigment. Organisms are acid fast negative.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Ovary: Granulomatous oophoritis with numerous intracytoplasmic Gram negative bacilli.

Contributor's Comment:

Brucella spp. are an important worldwide zoonotic pathogen of both human and veterinary medical significance. This genus was previous classified into six "classical" species based on preferential mammalian hosts including Brucella melitensis (goats), Brucella suis (suidae), Brucella abortus (cows), Brucella ovis (sheep), Brucella canis (dogs), and Brucella neotomae (desert rats).5 Newly identified marine mammal species include Brucella ceti (cetaceae) and Brucella pinnipedialis (pinnipeds).3 More recently, 'atypical' Brucella strains have been isolated from non-mammalian hosts including amphibians; a big-eyed tree frog, several African bullfrogs, a White's tree frog and a Pac-Man frog,1,2,8 however to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously described in toads.

Brucella spp. are facultative intracellular bacteria which exhibit a variety of lesions in amphibians, ranging from localized manifestations (e.g. subcutaneous abscess, skin lesions, swollen paravertebral ganglia, panopthalmitis) to systemic infection with high mortality in zoological exhibitions.6 In some species, however, the lack of pathogenic lesions suggests that Brucella spp. may be a commensal microorganism or at least a facultative pathogen. The precise epidemiology and pathogenesis of brucellosis in amphibians remains largely unknown, and limited data is available for the zoonotic potential of novel or 'atypical' members of the Brucella genus.

The marine toad, also known as the cane toad, is considered to be the most

widely introduced species in the world (Global Invasive Species Database. http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd).

Originally used to control insect pests of sugarcane and other crops, it is now

considered to be a pest species itself as it preys on and outcompetes native

amphibians. Its toxic secretions (bufotoxin) are known to cause illness and

death in dogs, cats, wildlife, and humans. This particular female toad and her

mate were used in a zoo outreach and education program. Due to the unknown

zoonotic disease risk of Brucella inopinata- like spp. in humans, all

exposed personnel were administered prophylactic antibiotics. This animal and

two others from the same shipment were culled. One of the other animals was

also infected with Brucella inopinata- like spp.

Contributing Institution:

Michigan State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

College of Veterinary Medicine

4125 Beaumont Road, Lansing, MI 48910

Phone: (517) 353-1683

animalhealth.msu.edu

JPC Diagnosis:

Ovary: Granuloma, focal.

JPC Comment:

As noted by the contributor, this case represents one of multiple recent discoveries of Brucella spp. in non-domestic species, particularly amphibians.

Brucella sp. are small (0.6 µm x 0.6-1.5 µm) gram-negative bacilli or coccobacilli that are typically intracellular, associated with chronic infections and abortion in both domestic and wildlife species.6

Host adapted species of Brucella have been emerging for millennia since the domestication of canines and ungulates. However, the disease now known as brucellosis was not identified until British Royal Army Medical Corps officers serving on the island of Malta during the 1850s noted British servicemen were developing fevers of unknown origin. In 1861 Dr. Jeffrey Alan Marston, a British Army surgeon, described the features of typhoid fever, differentiating it from the 'Undulant Fever' he observed on Malta during the previous decade. Over two decades later, David Bruce and Lady Bruce, with the assistance of Guiseppe Caruna Scicluna, first cultured and discovered the genus now known as Brucella. However, the source and route of infection remained unknown until Dr. Themistocles Zammit, a Maltese microbiologist, discovered the bacteria in the urine, blood, and milk of goats on the island in 1904. Further investigation found approximately 50% of Maltese goats to be seropositive, with approximately 10% secreting the pathogen into the milk. This was significant given the British military procured goat milk for consumption by its service members. The British military subsequently banned procurement of goat milk in 1906, resulting in a drop from 3631 cases between 1900 and 1906 to only 21 in 1907 and zero by 1909. Despite this early success, brucellosis persisted on Malta until the island was finally declared brucellosis free in 2005, nearly a century after Zammit's discoveries. This issue was largely due to approximately two-thirds of the goats on the island belonging to back-yard breeders with only one or two goats and exempt from or failed to cooperate with government driven eradication efforts.9

As noted by the contributor, Brucella sp. may be classified as 'typical' or 'atypical', with the former representing 'classical' or 'core' species such as B. melitensis as well as additional species such as B. pinnipedialis, B. ceti, and B. papionis that share >99% of the genome with identical or nearly identical 16S rRNA and recA gene sequences. In contrast, atypical species remain within the proposed species boundary of 95-96% nucleotide similarity but resemble members of genus Ochrobactrum, the nearest genetic neighbor within family Brucellaceae. Atypical species are often motile due to the presence of flagella and also demonstrate an increased ability to survive in low pH environments due to the presence of a glutamate decarboxylase-dependent system, a useful marker for distinguishing between typical and atypical genera.6

The similarity between atypical Brucella sp. and Ochrobactrum sp. has resulted in the former being misidentified as the latter when rapid identification techniques (e.g. API® 20NE test strips) are utilized. Ochrabactrum anthropi is an opportunistic pathogen associated with severe Brucella-like disease in immunocompromised patients and is closely related to Brucella sp. Therefore, real-time or conventional PCR targeting the IS711 insertion sequence common to all Brucella species or 16S rRNA sequencing should be considered following the diagnosis of Ochrobacterum sp. by conventional methods to rule out atypical Brucella.4

It is currently unknown if amphibian brucellosis occurs as the result of a commensal or facultative pathogen or as the result of direct pathogenicity. Furthermore, host species, geographic range, and range of affected species are currently unknown. Including this case, atypical Brucella isolates have been identified in at least ten amphibian species native to North and South America, Australia, and Africa. These isolates were obtained from zoologic collections (as in this case), wild caught specimens, private breeders, and pet stores. Given the emergence of brucellosis within amphibians, personnel responsible for care and treatment of these animals should not only be aware of the risk of brucellosis as a cause of morbidity and mortality in these species, but also the potential risk of zoonotic infection, though no reports of transmission have been reported.4

Based on the moderator's experience, anuran brucellosis frequently manifests as a musculoskeletal abscess associated with spherical foci of discoloration of the overlying skin, although coelomitis, and/or visceral abscesses may also be seen, such as in this case.

Brucella sp. in this case are readily identified using Gram stains (i.e. Brown-Hopps), however, this gram negative organism is often poorly discernable in tissue sections stained with both standard histochemical stains such as hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) as well as Gram stains. The moderator suggested performing acid-fast stains in such cases to exclude mycobacteria (which can cause similar lesions), followed by PCR as previously described.

Although intrahistocytic eosinophilic material is present within macrophages, participants agreed that coccobacilli could not be readily identified on H&E stained sections and therefore could not rule out other phagocytized material. In addition, participants preferred the morphologic diagnosis of "granuloma" rather than "oophoritis" due to the focally extensive distribution of the lesion, which was centered on regions of dropout interpreted to be necrosis, as well as features of granulomas, such as epitheliod macrophages surrounded by peripheral fibrosis and lymphocytes.

References:

1. Al Dahouk S, Köhler S, Occhialini A, et al. Brucella spp. of amphibians comprise genomically diverse motile strains competent for replication in macrophages and survival in mammalian hosts. Sci Rep. 2017; 7:44420.

2. Eisenberg T, Hamann HP, Kaim U, et al. Isolation of Potentially Novel Brucella spp. from Frogs. J Appl Microbiol. 2012; 78: 3753-3755.

3. Foster G, Osterman BS, Godfroid J, Jacques I, Cloeckaert A. Brucella ceti sp. nov. and Brucella pinnipedialis sp. nov. for Brucella strains with cetaceans and seals as their preferred hosts. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007; 57:2688-93.

4. Helmick KE, Garner MM, Rhyan J, Bradway D. CLINICOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES OF INFECTION WITH NOVEL BRUCELLA ORGANISMS IN CAPTIVE WAXY TREE FROGS ( PHYLLOMEDUSA SAUVAGII) AND COLORADO RIVER TOADS ( INCILIUS ALVARIUS). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2018;49(1):153-161.

5. Moreno, E. Retrospective and prospective perspectives on zoonotic brucellosis. Front Microbiol. 2014; 5: 213.

6. Mühldorfer K, Wibbelt G, Szentiks CA, et al. The role of 'atypical' Brucella in amphibians: are we facing novel emerging pathogens? J Appl Microbiol. 2017;122:40-53.

7. Schlafer DH, Foster RA. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2016:402-406.

8. Soler-Lloréns PF, Quance CR, Lawhon SD, et al. A Brucella spp. Isolate from a Pac-Man Frog (Ceratophrys ornata) Reveals Characteristics Departing from Classical Brucellae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016; 6:116.

9. Wyatt HV. Lessons from the history of brucellosis. Rev Sci Tech. 2013;32(1):17-25.