Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 10, Case 3

Signalment:

14-year-old male intact Golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia)History:

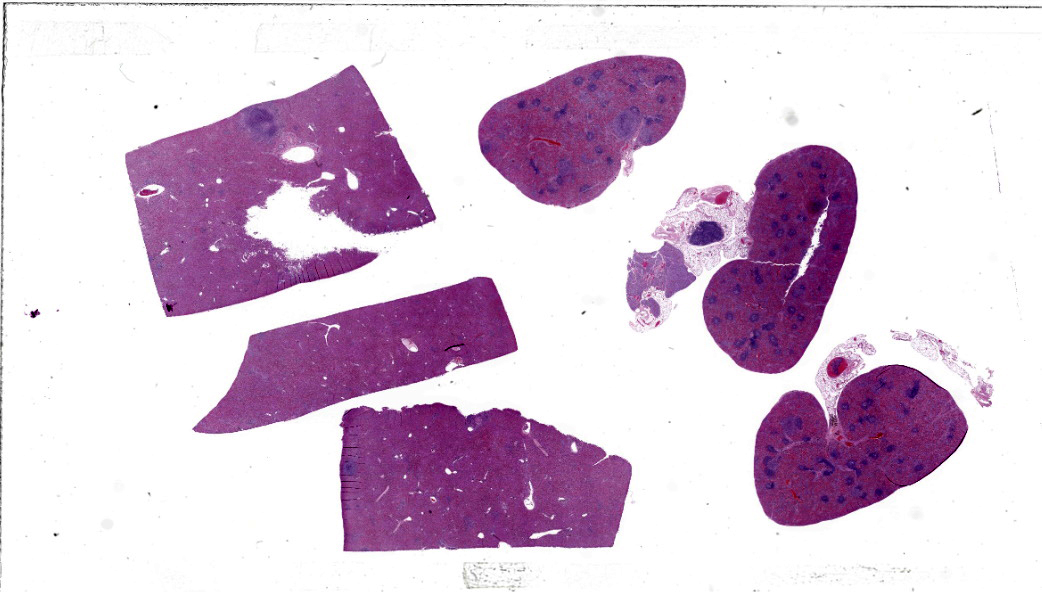

Gross Pathology: Approximately 20% of the hepatic and splenic parenchyma was effaced by approximately 30-40 pale tan, soft, well-demarcated foci ranging from pinpoint to 3 mm in diameter. The moderately distended gall bladder contained eight dark green choleliths ranging from 1 mm to 3 mm in diameter. Multiple lymph nodes (right mandibular, mesenteric, hepatic) were enlarged and oozed abundant pale tan purulent material on cut surface. Both kidneys had 10-15 multifocal to coalescing cystic dilations in the corticomedullary junction and medulla ranging from 2 to 5 mm in diameter. The cortex and medulla had approximately 20 multifocal punctate tan foci.Laboratory Results:

Postmortem aerobic culture of pooled mandibular lymph node and liver grew Listeria monocytogenes.Microscopic Description:

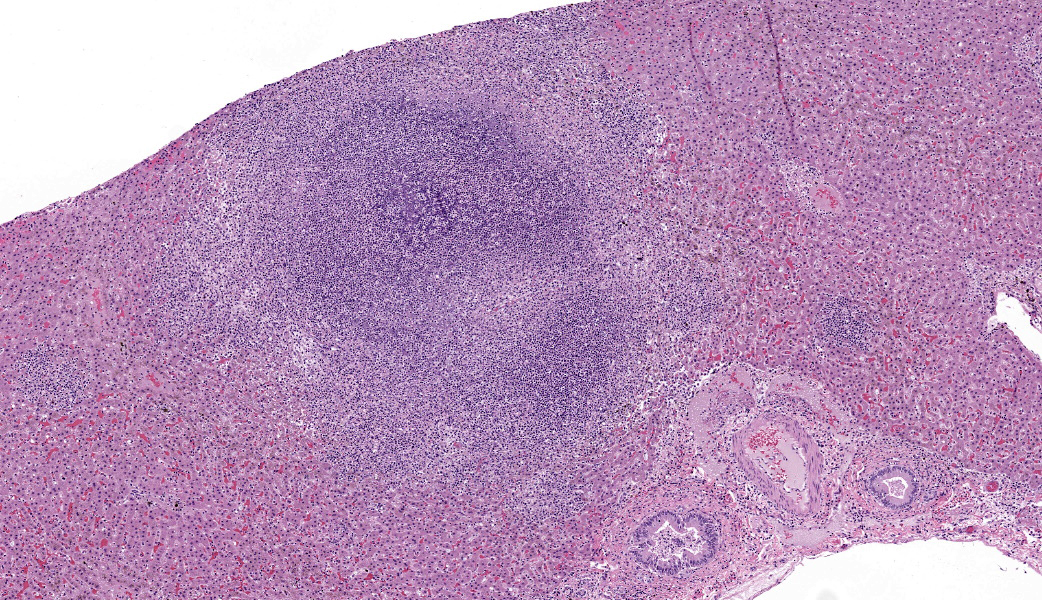

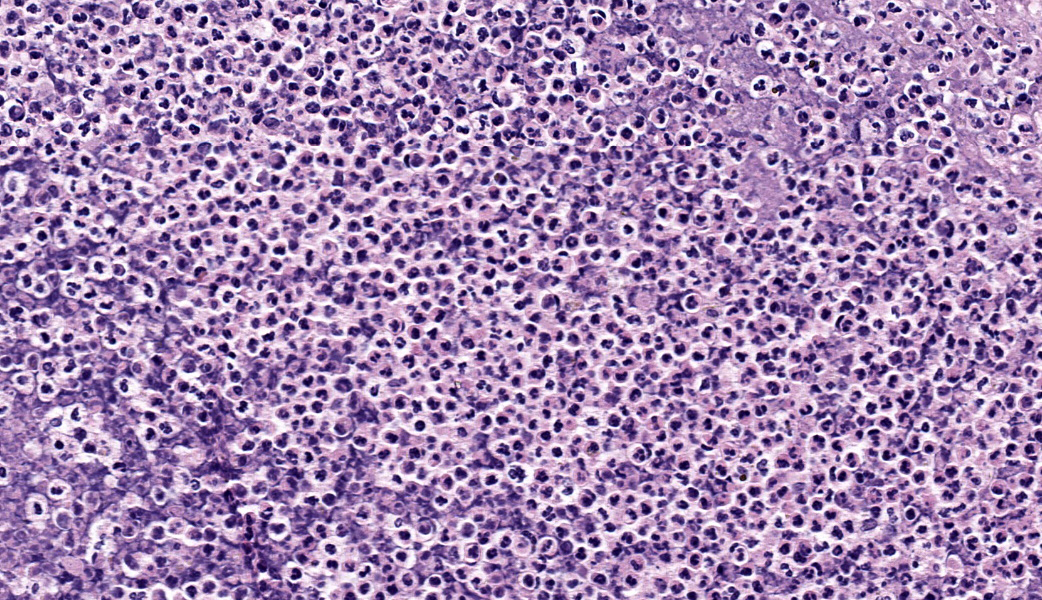

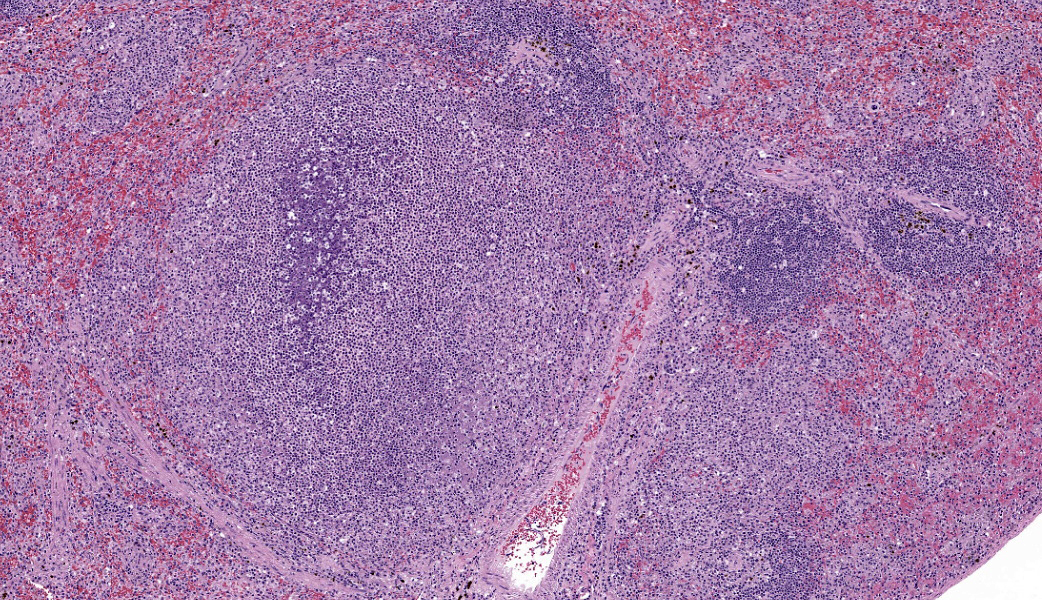

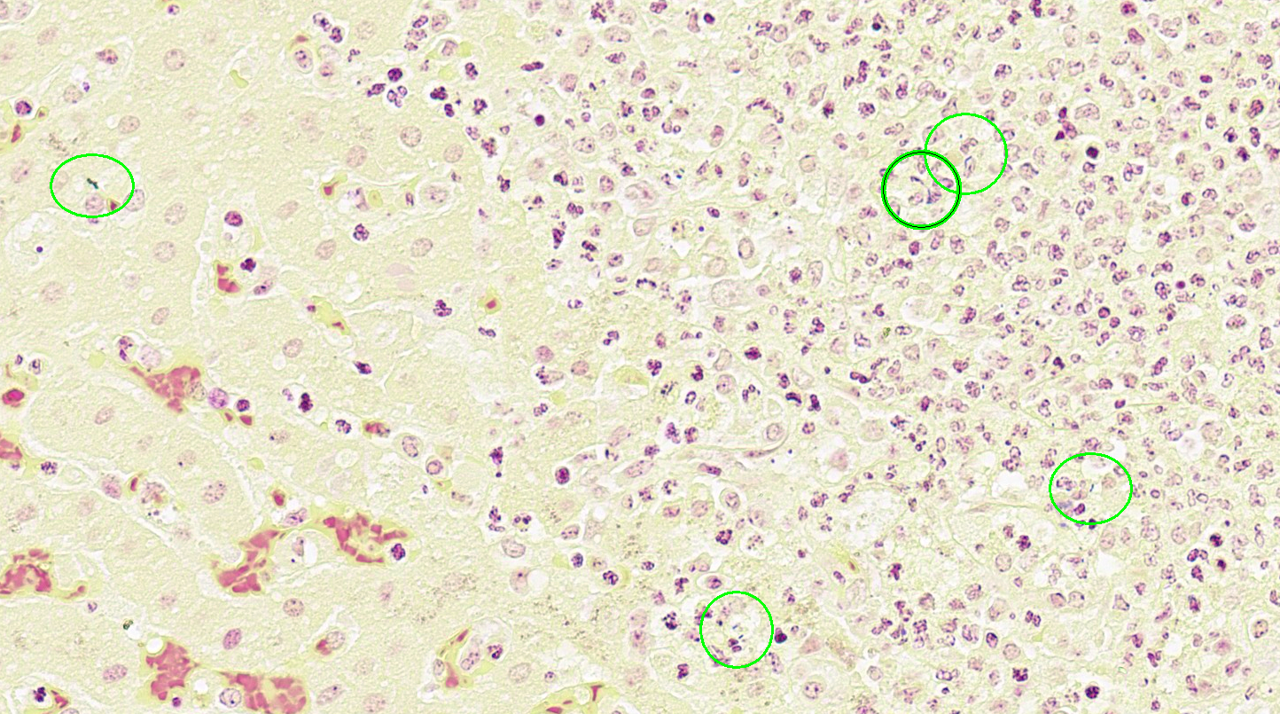

Liver: Approximately 40% of the hepatic lobular architecture is effaced by multifocal periportal to random discrete foci of lytic necrosis. Foci are composed of cellular debris, fibrin, myriad intact and fragmented neutrophils and moderate numbers of macrophages. There are small numbers of macrophages with tan to brown cytoplasmic pigment (hemosiderin vs. lipofuscin). Portal triads contain up to four biliary duct profiles (biliary hyperplasia) and are surrounded by moderate numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages. Moderate numbers of scattered hepatocytes contain brown granular cytoplasmic pigment (lipofuscin vs. hemosiderin) and cytoplasmic large discrete vacuoles. Multifocally, small hepatic vessels are partially occluded by aggregates of eosinophilic homogenous material interspersed with pyknotic debris, fragmented neutrophils, and macrophages (fibrin thrombi). Hepatic sinusoids are variably expanded with moderate numbers of erythrocytes (congestion), similar inflammatory infiltrates, and fibrin thrombi.Spleen: Approximately 20% of the splenic parenchyma is effaced by multifocal to coalescing foci of necrosis and inflammation (similar to those described in the liver). Multifocally, the center of lymphoid follicles is hypocellular with eosinophilic karyorrhectic debris, extracellular yellow brown pigment globules (hematoidin), and moderate numbers of macrophages containing yellow brown cytoplasmic pigment (suspect hemosiderin). Splenic vessels are multifocally partially occluded by fibrin thrombi.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Liver: Moderate subacute multifocal random necrosuppurative hepatitis with periportal lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic cholangiohepatitis and mild biliary hyperplasia

- Spleen: Moderate subacute multifocal necrosuppurative splenitis with lymphoid necrosis

Slides not submitted:

- Kidney: Moderate acute multifocal suppurative nephritis, severe chronic diffuse cystic nephropathy and glomerulosclerosis with tubular proteinosis and mineralization

- Gallbladder: Moderate cholelithiasis with mixed bacteria

- Lymph node, mesenteric: Severe acute subacute multifocal necrosuppurative lymphadenitis

Contributor's Comment:

The combined gross findings, aerobic culture results, and histologic changes are consistent with necrotizing hepatitis, splenitis, nephritis, and lymphadenitis secondary to Listeria monocytogenes (sections of kidney and lymph node not included in submission). Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive, facultative anaerobic, bacillary bacterium that is abundant in soil and an opportunistic foodborne pathogen. In humans, common sources of infection include dairy products and processed fruits and vegetables. In this tamarin, contaminated fruit is postulated as the source of infection.Infection in susceptible species can lead to various clinical syndromes, including gastroenteritis, septicemia, meningoencephalitis, abortion, and conjunctivitis. Reports of listeriosis in nonhuman primates are primarily focused on animal models of human abortion and fetal infection.5 Spontaneous listeriosis is rarely reported.2,6 Necrotizing hepatitis has been reported in a free-ranging Kenyan colubus monkey, and more recently, septicemic listeriosis was reported in a captive white-faced saki, which resulted in meningoencephalitis and hepatitis.2,6 Similarly, Listeria-associated hepatitis is rarely reported in humans.8 When reported in both humans and nonhuman primates, gross and histologic findings are similar to those described here. Grossly, the liver has multifocal pinpoint tan foci, which histologically correlate to multifocal areas of hepatic necrosis with infiltration of large numbers of neutrophils. Bacteria are not always histologically evident; therefore, culture is necessary for confirmatory diagnosis.2,6.8

As L. monocytogenes is an opportunistic pathogen, most infections are mild or subclinical. Multiple host risk factors contribute to severity of clinical disease. Neonates, pregnant animals, aged animals, and immunocompromised animals are most at risk for clinically significant disease. Chronic disease, including renal disease (as in this patient), liver disease, diabetes, and concurrent neoplasia all contribute to a poorer clinical presentation and prognosis.9

Infection occurs through ingestion and direct infection of enterocytes or invasion through Peyer’s patches.7 Gastroenteritis is a possible consequence of intestinal colonization, but not essential for systemic infection to occur. Rodent studies demonstrate that bacteria can cross the intestinal barrier within minutes of infection, and systemic infection can occur without histologically evident gastroenteritis.3,4 Following intestinal infection, L. monocytogenes spreads to the liver through portal circulation, where it infects and proliferates within Kupffer cells and hepatocytes. In immunocompetent patients, infection is usually limited in the liver by activated macrophages and cytotoxic T-cells.9 In acute infection, NK cells produce INF-γ, activating macrophages, which act to eliminate bacteria. In chronic infection, cytotoxic T-cells act to eliminate cells infected with L. monocytogenes.1 In immunocompromised patients, infection can persist, and in some cases, become multisystemic through bacteremia and subsequent septicemia, as reported here.

Listeria monocytogenes has multiple key virulence factors involved in epithelial cell invasion (Internalin1A and Internalin1B), intracellular survival (hemolysin/lysteriolysin O), and cell-to-cell spread (ActA).9,10 Internalin1A and Internalin 1B allows L. monocytogenes to infect non-phagocytic cells by interacting with lysteriolysin O to form a membrane pore through which the bacteria can enter the cell.1,10 When engulfed by phagocytic cells, L. monocytogenes evades destruction by escaping the phagolysosome with listeriolysin O and phospholipases.1,10 Once the bacteria are cytoplasmic, replication can occur. The virulence factor ActA then aids in cell-cell transfer by altering the cell cytoskeleton (actin filaments) to facilitate transfer of bacteria between cells.1,10 In addition to aiding in phagolysosome escape, listeriolysin O and phospholipases aid in formation of bacteria-filled extracellular vesicles, which can be phagocytized by neighboring cells, leading to infection.1,10

Contributing Institution:

University of Wisconsin – Madison, School of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathobiological Sciences

JPC Diagnoses:

- Liver: Hepatitis, necrosuppurative, acute, multifocal, moderate, with fibrin thrombi.

- Spleen: Splenitis, necrosuppurative, acute, multifocal, moderate, with fibrin thrombi.

JPC Comment:

The contributor of this case wrote an excellent comment about Listeria monocytogenes; many topics of conference discussion focused on points from their write-up. Because the organisms were not visible without gram staining, this case proved challenging for conference participants, which some wondering about a protozoal cause for the lesions and others tentatively speculating about bacterial sepsis. Gram stains were performed in house at the JPC and revealed scattered, usually individualized, gram-positive bacilli, consistent with the Listeria monocytogenes identified by the contributor in this case.Listeria monocytogenes is a resistant creature that is capable of withstanding harsh environments. It is not an organism one ever hopes to encounter in real life, but nevertheless, it occasionally finds a way to make headlines. Listeria is an intracellular pathogen that, as participants found, is very difficult to see on routine H&E staining. It is known to cause encephalitis and abortions but can also cause septicemia in some affected animals. It has an arsenal of virulence factors at its disposal that were nicely covered by the contributor and could make for easy boards-fodder.

LTC Cudd recounted a story about one of these virulence factors that may assist other residents in committing it to memory. She said that, during her residency, a resident-mate of hers found a video on YouTube of Listeria monocytogenes bacteria moving around within a cell using their ActA protein, which co-opts host cell actin to facilitate intracellular movement of the bacterium, as well as to transfer bacteria from cell to cell. The polymerized actin tails look like tiny “comets” or “rockets.” In light of this, they adopted the term “Actin-A rockets” for Listeria. Having since watched this video, the bacteria do, in fact, look like microscopic rockets complete with fiery tails shooting around inside of the infected host cell. For educational (and entertainment) purposes alike, consider it recommended to go watch the video.

References:

- Coelho C, Brown L, Maryam M, et al. Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors, including listeriolysin O, are secreted in biologically active extracellular vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(4):1202-1217.

- Kock ND, Kock RA, Wambua E, et al. Listeriosis in a free-ranging colobus monkey (Colubus guereza caudatus) in Kenya. The Vet Rec. 2003:152:141-142.

- Marco AJ, Prats N, Ramos JA, et al. A microbiological, histopathological and immunohistological study of the intragastric inoculation of Listeria monocytogenes in mice. J Comp Pathol. 1992;107(1):1-9.

- Pron B, Boumalia C, Jaubert F, et al. Comprehensive study of the intestinal stage of listeriosis in a rat ligated ileal loop system. Infect Immun. 1998;66(2):747-755.

- Schuppler M, Loessner M. The Opportunistic Pathogen Listeria monocytogenes: Pathogenicity and Interaction with the Mucosal Immune System. Int J Inflam. 2010:704321.

- Smith MA, Takeuchi K, Brackett RE, et al. Nonhuman primate model for Listeria monocytogenes-induced stillbirths. Infect Immun. 2003;71(3):1574-1579.

- Struthers JD, Kucerova Z, Finley A, Goe A, Huffman J, Phair K. Septicaemic Listeriosis in a White-Faced Saki (Pithecia pithecia). J Comp Pathol. 2022;194:7-13.

- Vargas V, Alemán C, de Torres I, et al. Listeria monocytogenes-associated acute hepatitis in a liver transplant recipient. Liver. 1998;18(3):213-215.

- Vazquez-Boland JA, Kuhn M, Berche P, et al. Listeria Pathogenesis and Molecular Virulence Determinants. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(3):584-640.

- Zachary JF. Mechanisms of Microbial Infections. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2022.