Signalment:

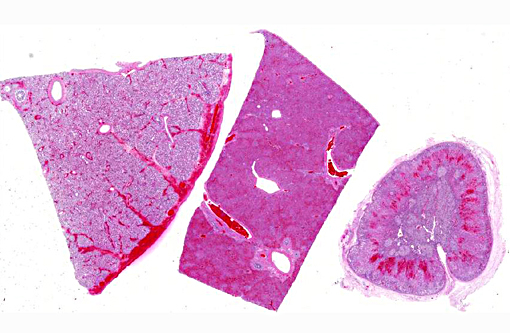

Gross Description:

The abdomen contained approximately 500-700 mls of yellow-brown cloudy fluid. The liver was diffusely dark red-brown with slightly rounded edges with many, small, randomly scattered, pinpoint white foci scattered throughout. The spleen was moderately enlarged, dark red-black and oozed blood on cut surface. Frequent tiny petechia were scattered on the serosa of the gastro-intestinal tract.

Histopathologic Description:

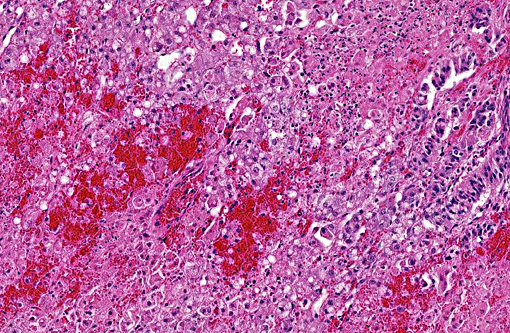

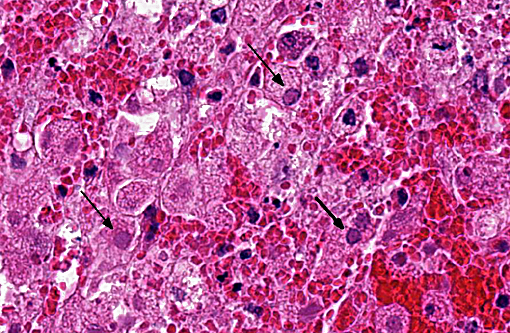

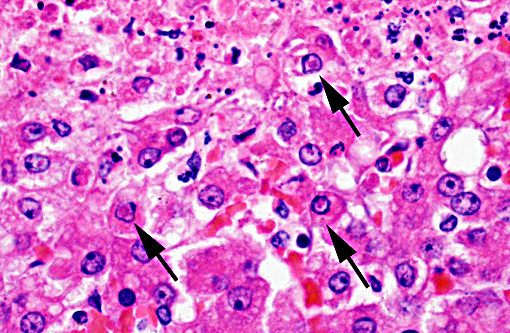

Hepatic sinusoids were often mildly congested. Frequent, randomly scattered foci of lytic necrosis were present throughout the sections. Within these foci, hepatocytes were replaced by pale proteinaceous debris admixed with sparse karyorrhectic debris. Hepatocytes at the margins of these foci sometimes contained pale pink, intranuclear inclusions. Rare dense aggregates of bacteria were noted within sinusoids.

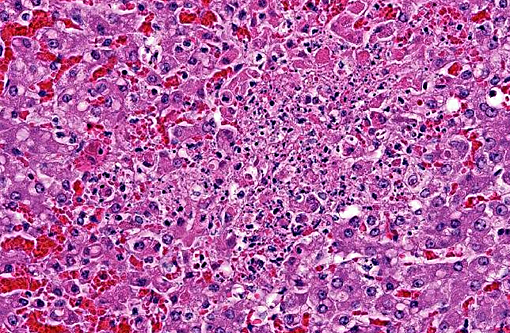

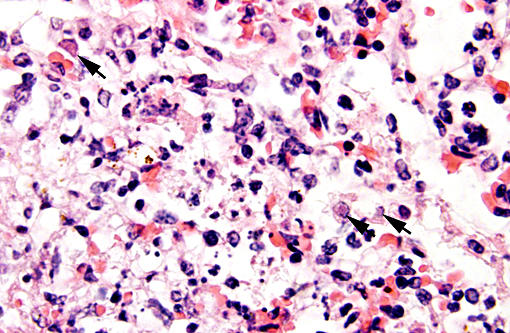

There were frequent, multifocal to coalescing areas of hemorrhage and lytic necrosis within the adrenal cortex. Adrenocortical cells at the periphery of areas of necrosis also often contain INIBs similar to those described above. Small foci of acute lytic necrosis were noted in the spleen and thymus.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Lung: Severe, diffuse, acute, pulmonary congestion and edema with frequent foci of hemorrhage and occasional, mild, multifocal (embolic), fibrinonecrotizing, pneumonia with rare intranuclear inclusion bodies (INIBs).

2. Liver: Moderate, acute, multifocal and random, necrotizing hepatitis with intrahepa-tocellular INIBs.

3. Adrenal gland: Severe, acute, multifocal to coalescing, necrotizing and hemorrhagic, adrenalitis with INIBs.

Lab Results:

Antemortem blood cultures - Actinobacillus equuli and Streptococcus sp. were isolated.

Fecal culture (antemortem sample) - no Salmonella sp. isolated

Aerobic cultures of lung and liver (postmortem samples) - no microbial growth

RT-PCR on pooled liver and lung samples - positive for Equine herpesvirus-1

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Generalized neonatal disease, as demonstrated in this case, is also reported where foals infected in utero may be born alive. As in this case, infected foals generally die in the first few days of life due to acute interstitial pneumonia, pulmonary edema, and secondary septicemia. Actinobacillus equuli and Streptococcus sp. are commonly isolated agents. Interestingly, one reference(2) indicated that while areas of hepatic necrosis are common in aborted fetuses, such lesions are generally not present in neonatal foals succumbing to systemic EHV-1 infection. However, in this 5 day old foal, hepatic necrosis with INIBs was a prominent finding.

In natural disease conditions, EHV-1 infects epithelial cells in the upper respiratory tract which may cause mucosal damage, predisposing affected horses to infection with other respiratory pathogens (bacteria, fungi, etc). Subsequent infection of circulating leukocytes (typically monocytes and T cells) enables the virus to disseminate to other organs including the uterus and central nervous system. Infection of endothelial cells in the gravid uterus and CNS (in neurologic cases) may result in vasculitis and thrombosis. Acute and severe disruption of placental circulation is likely responsible for the sudden death and expulsion of fresh fetuses which is characteristic of EHV-1 abortion.(1)

Exposure to EHV-1 is very common in most horse populations. Horses, including foals and young horses, in large breeding/training facilities are often seropositive for EHV-1, with or without any signs of respiratory disease.(1) Infections are usually acquired via nasal secretions from the dam, other foals, pasture mates, and/or from contact with fomites. Latent infections are common; the virus may be harbored in the trigeminal ganglia or in lymphoid cells. Latently infected horses do not shed virus and are clinically normal. However, under certain conditions, there may be reactivation of the virus and recrudescence of infection. The virus can be reactivated experimentally in horses by admi-nistration of high doses of glucocorticoids. Stressful situations such as transport, sales, competitions, or mixing of horses, as well as immunocompromise due to concurrent disease, are thought to be factors leading to recrudescence of disease. In closed herds, abortions due to EHV-1 infection are often attributed to recrudescence of infection in individuals, which may or may not be accompanied by clinical disease, and who subsequently may shed virus and act as a source of infection to other exposed, susceptible horses.(1) There was frequent movement of horses within the barn that this mare and foal originated from, so both late gestational infection and/or recrudescence of infection in the mare are possibilities in this case.

JPC Diagnosis:

Adrenal gland: Adrenalitis, necrotizing and hemorrhagic, multifocal to coalescing, severe with intranuclear viral inclusion bodies.

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, multifocal and random, marked with intranuclear viral inclusion bodies.

Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, necrotizing, diffuse, mild with necrotizing vasculitis and intranuclear viral inclusion bodies.

Conference Comment:

Equine herpesvirus infection within the central nervous system is less common than the respiratory and abortive manifestations of EHV-1, only occurring in a small percentage of infected horses. However, the neurologic form can be particularly devastating, ultimately resulting in a vascular origin myeloencephalitis, which begins with an upper respiratory infection as described above. The precise factors determining why some horses develop neurologic signs is not well understood, but may be related to infection with certain virus strains. In contrast to CNS herpes viral infections in some other domestic species (bovine IBR, porcine pseudorabies), EHV-1 is not neuronotropic, although neurons and astrocytes may become infected, and the CNS form of the disease is more commonly seen in adult horses. Circulating infected cells, primarily T lymphocytes and monocytes, spread the virus to endothelial cells of small vessels of the CNS resulting in vasculitis, thrombosis and infarction of tissues supplied by those vessels. Lesions can occur throughout the CNS, including the spinal cord, but inclusion bodies within the CNS are generally not seen.(5) Gross lesions consist of randomly distributed areas of malacia with accompanying hemorrhage and edema,(4) reflecting the vascular nature of the lesion.

References:

1. Njaa, BL. Disorders of horses. Viral causes of abortion and neonatal loss. In: Kirkbride's Diagnosis of Abortion and Neonatal Loss in Animals. 4th ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell;2012:154-157.

2. Maxie MG. Equid herpesvirus 1 abortion in horses. In: Maxie MG ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:532-533. .

3. Dunowska M. A review of equid herpesvirus 1 for the veterinary practitioner. Part B: Pathogenesis and epidemiology. N Z Vet J. 2014;62(4):179-188.

4. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of Microbial Infections. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:228-229.

5. Zachary JF. Nervous System. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:840-841.