Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 18, Case 3

Signalment:

13-year-old male elegant crested tinamou (Eudromia elegans.

History:

This elegant crested tinamou (Eudromia elegans) was housed in a zoological collection, and was euthanized due to marked weight loss and declining clinical condition. He had a history of chronic articular gout of the right third digit and mild lateral deviation of the rhinotheca resulting in malocclusion (“scissor beak”).

Gross Pathology:

Gross examination confirmed beak malocclusion and a focal swelling over the proximal aspect of the right third digit that exuded white chalky to pasty material from cut surfaces. The animal was in thin body condition, with scant subcutaneous and intracavitary adipose tissue stores. The crop was moderately distended with fresh vegetables, the proventriculus was empty, and the ventriculus was filled with vegetable ingesta, small pebbles, and a small amount of green, pasty material. The intestines and ceca contained a small amount of green-brown, pasty digesta.

Laboratory Results:

Cytologic evaluation of liver, spleen, and lung impression smears was unremarkable.

Microscopic Description:

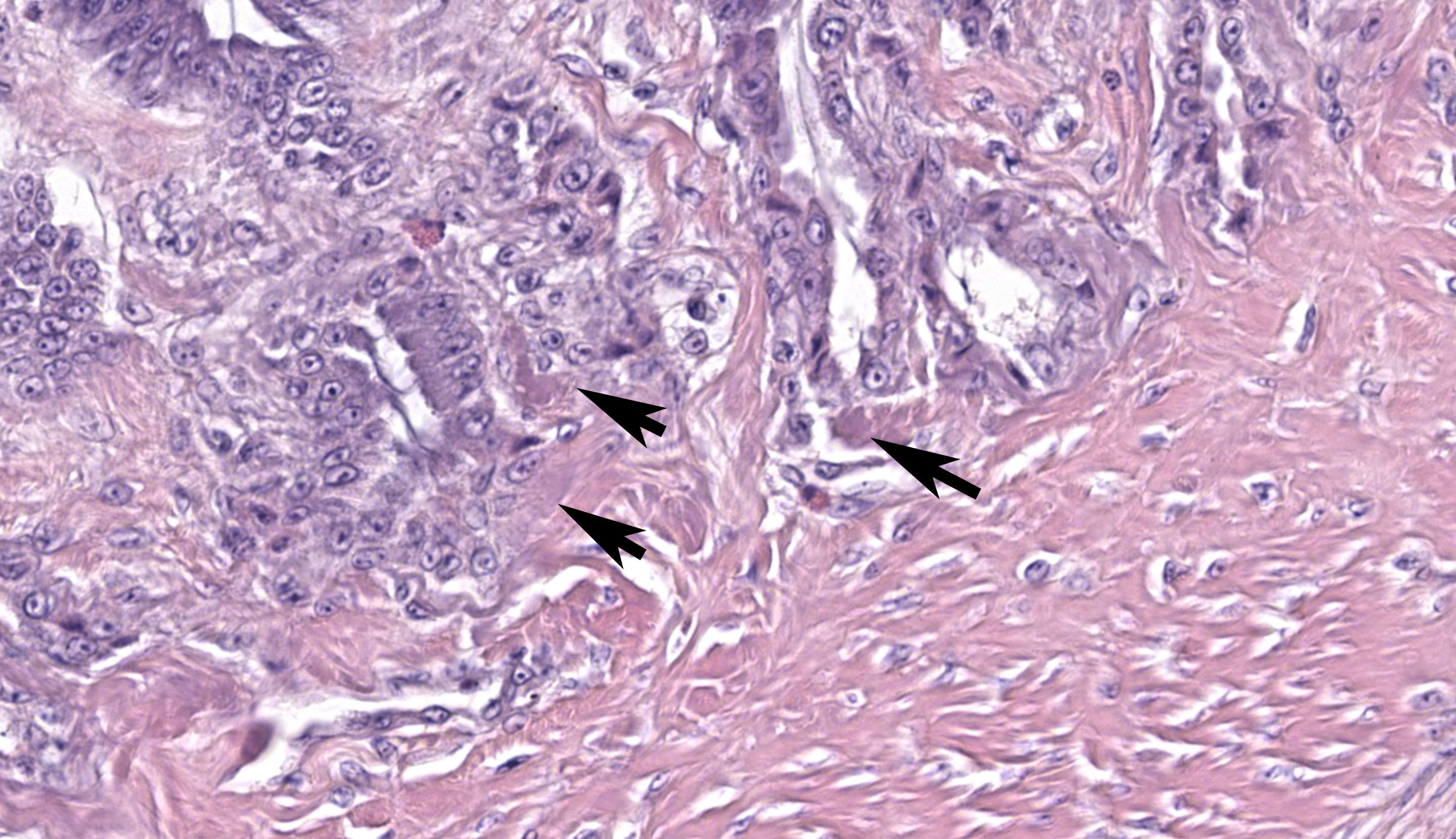

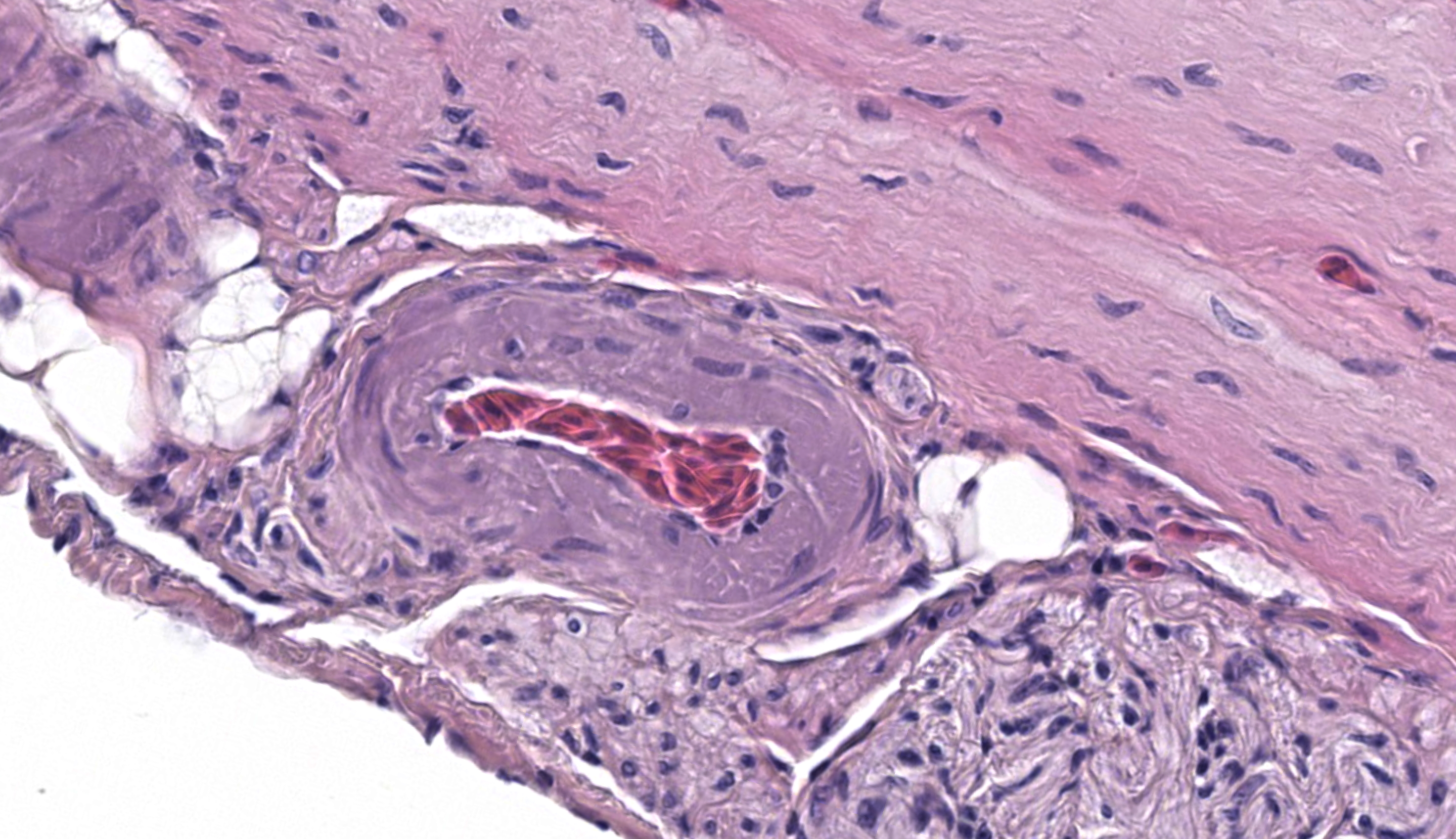

Ventriculus: Throughout the section, the koilin layer is diffusely, superficially disrupted and separated by a dense mat of elongate yeasts. The yeasts are approximately 2-3 micrometers wide and 20-40 micrometers long. They aggregate in haphazard orientations on the surface, and also stream into ventricular glands in roughly parallel-oriented, ‘logjam-like’ arrangements, rarely reaching the deepest portions of the glands. The lamina propria contains a scant infiltrate of granulocytes and rare lymphocytes that rarely extends into the mucosal epithelium. Small, subepithelial pools of eosinophilic to amphophilic, smudgy, acellular material are scattered throughout the lamina propria. Small-caliber blood vessels in the mucosa and tunica muscularis are multifocally surrounded by low numbers of mononuclear cells. Arterioles throughout the tunica muscularis and subtending the serosal surface are variably expanded by smudgy, eosinophilic, acellular material that partially or wholly obscures normal cellular detail in the arteriolar walls.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Ventriculus: Ventriculitis, heterophilic and lymphocytic, chronic, multifocal, mild, with superficial koilin disruption and myriad surface-associated yeasts

Ventriculus: Amyloidosis, arteriolar and subepithelial, chronic, multifocal, mild to moderate

Contributor’s Comment:

Histopathology in this elegant crested tinamou revealed florid superficial colonization of the mucosal surface of the proventricular-ventricular isthmus and ventricular koilin by elongate yeasts. The morphology and tissue distribution of the yeasts are characteristic of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster. Arteriolar and subepithelial amyloid deposition, while relatively mild in sections of the gastrointestinal tract, were manifestations of multi-organ amyloidosis that was considered to be the most important factor in this bird’s clinical decline.

Macrorhabdiosis, or ‘avian gastric yeast’ infection, is a well-recognized condition in various avian species. The causative organism, Macrorhabdus ornithogaster, was famously misinterpreted to be a large bacterium (“megabacteria”) after its discovery but is now recognized as an ascomycetous yeast.9 The yeasts have a distinctive elongate morphology, measuring approximately 2-3 micrometers wide and 20-40 micrometers long, and are often arranged in densely packed clusters or streams, sometimes referred to as ‘haystack,’ ‘matchstick,’ or ‘logjam’ arrangements.7,9 Infections occur at the mucosal surface of the proventricular-ventricular isthmus, with organisms sometimes penetrating into isthmus glands and extending into the koilin layer of the ventriculus. Organisms can be detected in cytologic preparations of feces or scrapings from the isthmus. Although staining characteristics can be variable, they are typically gram-positive and stain dark blue with rapid Romanowsky stains (e.g., Diff-Quik).4 In histologic sections, the yeasts are eosinophilic and often readily identifiable with routine hematoxylin and eosin staining. They also stain positively with silver stains and Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain.

Gross lesions can include emaciation, excessive proventricular mucus production, and mucosal erosions or ulcerations with hemorrhage. Histologic examination reveals variable associated inflammation and goblet cell hyperplasia in addition to the characteristic organisms. In the ventriculus, colonization can be associated with marked disruption and attenuation of the koilin layer, with variable inflammation. An association with proventricular adenocarcinoma in budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulates) has been proposed, but the mechanism of this association is not well understood.5

Macrorhabdiosis can be subclinical or can be associated with a chronic, progressive, and fatal wasting syndrome.7 Clinically significant or fatal disease associated with Macrorhabdus ornithogaster infection is most often diagnosed in psittacine, passerine, and gallinaceous species, but has also been reported in paleognaths such as ostriches and rheas.1,2,3,6,8,10 While not, to our knowledge, previously reported in tinamous (also paleognaths), macrorhabdiosis has been diagnosed in one previous case from our zoological collection.

In some cases, an underlying stressor may be needed to trigger the development of clinically significant disease.6,7 Yeasts were abundant in multiple sections of the orad ventriculus from this case, but no clear indications of chronicity, such as chronic inflammation or goblet cell hyperplasia, were observed. We suspect that the yeast overgrowth may have occurred in a relatively short period prior to death, potentially as a consequence of debilitation due to underlying disease. This tinamou’s clinical decline was attributed primarily to multi-organ amyloidosis involving the liver, spleen, kidneys, myocardium, and arteries in multiple tissues, confirmed by Congo red staining of selected tissues. While suspected to be a sequela of chronic inflammation, a specific inciting cause for amyloidosis was not determined. The contribution of macrorhabdiosis to this tinamou’s clinical decline is unclear.

Contributing Institution:

Wildlife Conservation Society, Zoological Health Program

https://oneworldonehealth.wcs.org

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Ventriculus: Koilin loss, diffuse, severe with myriad elongate yeast and mild granulocytic ventriculitis

2. Ventriculus (lamina propria and blood vessels): Amyloidosis, chronic, multifocal, mild

3. Adipose tissue: Atrophy, subacute, diffuse, mild

JPC Comment:

Case 3 offers a synopsis of classic avian lesions. We differ slightly from the contributor in identifying the primary lesion as koilin loss (which was substantial) though we agree that there is mild inflammation of the ventriculus. We added an additional morphologic diagnosis for the atrophy of fat (best observed at the serosal surface) as adipocytes are small with variably sized lipid vacuoles. Amyloid deposition in this case is subtle and easily overlooked on H&E. On this slide, amyloid is most discernable within sagittal sections of larger vessels and multifocally within the lamina propria as lightly eosinophilic to amphophilic material. In birds, common locations for amyloid deposition include the kidney (glomerulus and basement membrane), the liver (within the space of Disse), and the spleen. While we searched for a urate tophus (i.e. gout) to connect back to the clinical picture outlined by the contributor, we were unable to make this case a ‘four-fer’.

The long sagittal sections of peripheral nerves (likely a nerve plexus) prompted a short group discussion. In a vacuum, this might resemble ganglioneuritis (i.e. avian bornavirus). As Dr. Ladouceur noted, avian nervous tissue is highly cellular and satellite cells could be confused for infiltrating T-lymphocytes. Once again, considering avian type is helpful as avian bornavirus affects psittacine birds (and rarely passerines) and not tinamiforms such as this tinamou. If this were a psittacine, CD3 IHC can be useful in differentiating satellite cells from infiltrating T lymphocytes in cases of suspected avian bornavirus. Screening HE sections for plasma cells is also useful (none were noted in the nerves in this case).

References:

- Crespo R, França MS, Fenton H, Shivaprasad HL. Galliformes and Columbiformes. In: Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J, eds. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier; 2018: 747–73.

- Huchzermeyer FW, Henton MM, Keffen RH. High mortality associated with megabacteriosis of proventriculus and gizzard in ostrich chicks. Vet Rec. 1993; 133: 143-144.

- Martins NRS, Horta AC, Siqueira AM, Lopes SQ, Resende JS, et al. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in ostrich, rhea, canary, zebra finch, free range chicken, turkey, guinea-fowl, columbina pigeon, toucan, chuckar partridge and experimental infection in chicken, japanese quail and mice. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2006; 58(3): 291-298.

- Phalen DN. Update on the diagnosis and management of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster (formerly Megabacteria) in avian patients). Vet Clin Exot Anim. 2014; 17: 203-210.

- Powers LV, Mitchell MA, Garner, MM. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster Infection and Spontaneous Proventricular Adenocarcinoma in Budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulates). Vet Pathol. 2019; 56(3): 486-493.

- Reavill DR, Dorrestein G. Psittacines, Coliiformes, Musophagiformes, Cuculiformes. In: Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J, eds. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier; 2018: 775-798.

- Schmidt RE, Reavill DR, Phalen DN. Gastrointestinal System and Pancreas. In: Schmidt RE, Reavill DR, Phalen DN. eds. Pathology of Pet and Aviary Birds, Second Edition. Iowa State Press. Ames, Iowa. 2015: 65, 70, 81.

- Smith DA. Palaeognathae: Apterygiformes, Casuariiformes, Rheiformes, Struthioniformes; Tinamiformes. In: Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J, eds. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier; 2018: 633-648.

- Tomaszewski EK, Logan KS, Snowden KF, et al. 2003. Phylogenetic analysis identifies the “megabacterium” of birds as a novel anamorphic ascomycetous yeast, Macrorhabdus ornithogaster nov., sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003; 53(4):1201–1205.

- Trupkiewicz J, Garner MM, Juan-Sallés C. Passeriformes, Caprimulgiformes, Coraciiformes, Piciformes, Bucerotiformes, and Apodiformes. In: Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J, eds. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier; 2018: 799-823.