Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

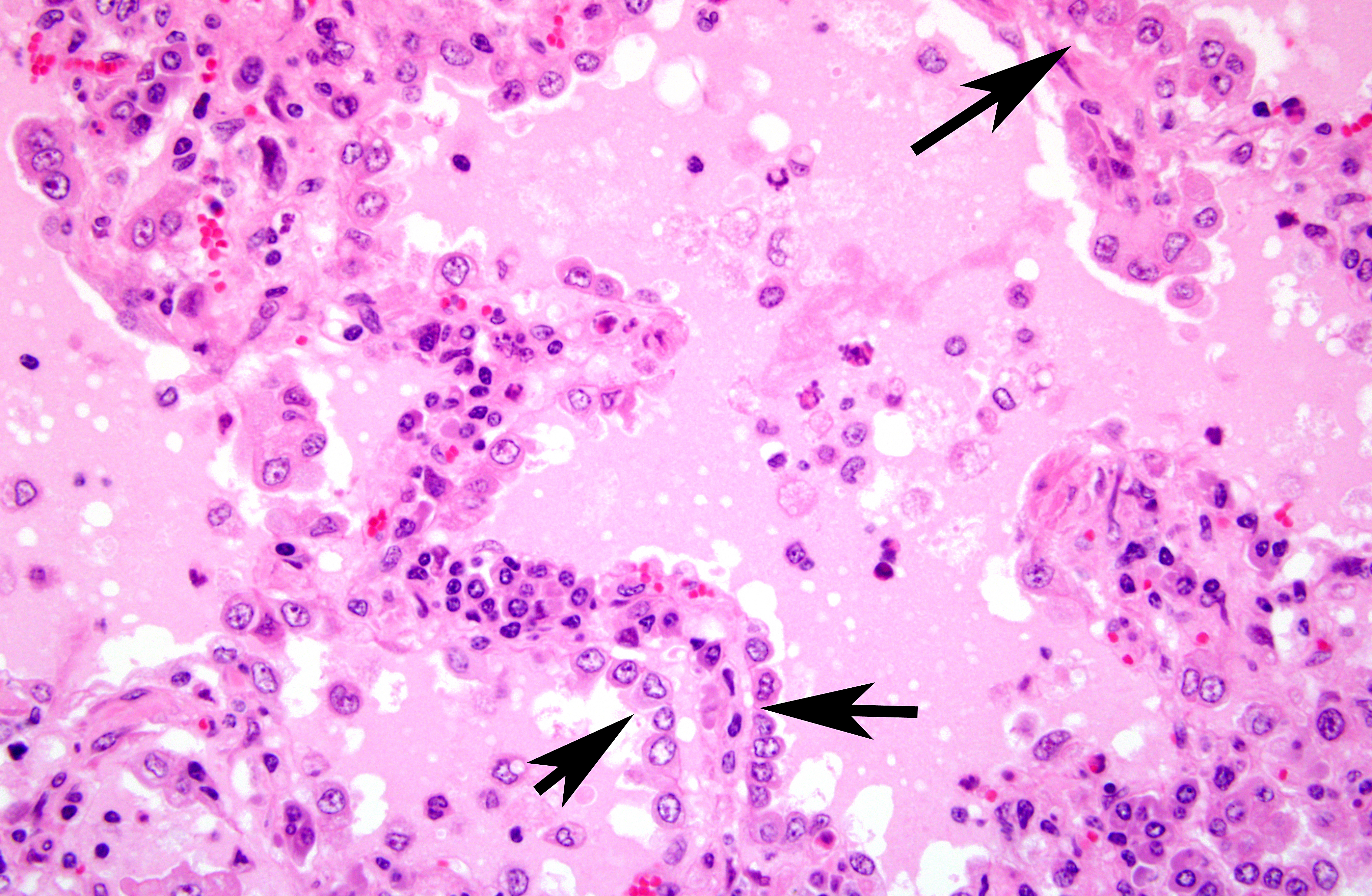

Alveolar septa were thickened with infiltrates of lymphocytes and the hyperplasia of type II pneumocytes. Alveoli were filled with eosinophilic fluid, small amounts of fibrin, neutrophils and macrophages. Occasionally, macrophages phagocytizing eosinophilic fluid were seen.

Both carpal joints had arthritis and periarthritis characterized by the villous proliferation of the synovial membrane, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and necrosis of the tendon sheath.

In mammary glands, periductal infiltration of lymphocytes and many abscesses were observed. No lesion was found in the central nervous system.

Immunohistochemically, the eosinophilic materials in alveoli were positive for anti-surfactant protein A antibody (Chemicon). Furthermore, immnohistochemical examination with anti-CD3 (DAKO), anti-CD79a (DAKO), anti- CD68 (DAKO) antibodies showed that the most of lymphocytes around blood vessels and airways were Tlymphocytes that can relate to the cell-mediated immunity. Pasteurella multocida antigens were detected in the area of bronchopneumonia. Immunohistochemical detection of CAE virus antigens was not successful.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Etiology: CAE

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The lesions of the lung in the present case consisted of those of typical CAE which are characterized by the lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in septa with the type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, infiltration of lymphocytes around blood vessels, bronchi, and bronchioles, and eosinophilic exudates in alveoli(1,4). Distinctive eosinophilic fluid is an important finding for differential diagnosis between CAE and maedi(4).

The present case had lymphoplasmacytic arthritis and periarthritis with villous proliferation of the synovium, which are suggestive of CAE(6). In the mammary gland, many abscesses and periductal cuffs consisting of lymphocytes were seen. Unlike abscesses caused by Arcanobacterium progenies infection, the infiltration of lymphocytes around ducts was a characteristic finding of the nonsuppurative mastitis caused by CAE virus(5).

Although the serum was weakly positive for CAE virus antibody by AGID test, pathological findings in this case were identical to those of CAE virus infection. Pasteurella multocidainfection of the lung might be a secondary infection to CAE.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Conference participants discussed the primary differential diagnosis for nonsuppurative interstitial pneumonia in sheep and goats, and a primary consideration for many was ovine progressive pneumonia (OPP) - also known as maedi, to which goats are also susceptible, and which is more common than the pneumonia form of CAE in the United States. One difference between OPP and CAE is that type II hyperplasia and eosinophilic alveolar fluid is not a prominent feature of OPP. Additionally, type II pneumocyte hyperplasia is not prominent in OPP because the type I pneumocytes remain uninjured(4). Both have a typical gross appearance of heavy, rubbery, pale gray lungs that fail to collapse. Another consideration for the florid type II pneumocyte hyperplasia seen in this case is ovine pulmonary adenomatosis caused by ovine retrovirus (also known as jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus - JSRV), which rarely affects goats(1). An associated clinical sign of jaagsiekte is the drainage of fluid from the nose following elevation of the hind limbs. A final cause of lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia in sheep and goats is parasitic pneumonia caused by Meullerius capillaries.

The section of lung in this case demonstrates a typical histologic appearance of CAE and other lentiviruses affecting sheep and goats, with a sharp demarcation between affected and unaffected lung. The copious proteinaceous fluid filling the alveoli in this section is visually distinct from edema fluid, and is also very characteristic of this disease. The moderator pointed out that there was no corroborative evidence to attribute the prominent eosinophilic fluid to hydrostatic edema, such as dilated lymphatics and rarefaction around blood vessels. This fluid has been shown to contain pulmonary surfactant, which is consistent with the abundant type II pneumocyte hyperplasia. As the virus destroys type I pneumocytes, and type II pneumocytes proliferate, the local environment becomes hypoxic due the thickening of the interstitium, which also fills with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages. As the diffusion capacity of the lung decreases, cells release hypoxia-induced factor-1α, which activates the transcription of vascular endothelial growth factor, increasing vascular permeability and the leakage of high protein plasma fluid(3). The interstitial pneumonia seen with CAE results from infected macrophages expressing IL-8, which recruits additional inflammatory cells, perpetuating the inflammatory cycle(8).

References:

2. Konishi M, Tsuduku S, Haritani M, Murakami K, Tuboi T, Kobayashi C, Yoshikawa K, Kimura K and Sentsi H: An epidemic of caprine atthritis-encephalitis in Japan: Isolation of the virus. J Vet Med Sci 66: 911-917, 2004

3. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fauster N, Aster JC. Cellular response to stress and toxic insults: adaptation, injury, and death. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fauster N, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA:Saunders Elsevier; 2010:45.

4. L³pez A. Respiratory system, mediastinum, and pleura. In: McGavin MD, Zachry JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO:Mosby; 2011:517-18.

5. Phelps SL and Smith MC: Caprine arthritis-encephalitis virus infection. J Am Vet Med Assoc 203:1663-1666, 1993

6. Thompson K: Viral arthritis. In: Pathology of domestic animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th eds., vol. 1, pp. 170-171. Saunders, Edinburgh, UK, 2007

7. World Organisation for Animal Health: Caprine arthritis-encephalitis and Maedi-visna. In: OIE manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals 2008, Chapter 2.7.3/4. [cited 2009 Jun 1]. Available from http://www.oie.int/eng/normes/mmanual/2008/pdf/2.07.03-04_CAE_MV.pdf

8. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infections. In: McGavin MD, Zachry JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO:Mosby; 2011:216.