Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 25

1 May 2019

CASE II: 2014 Case 2 (JPC 4050143)

Signalment: Juvenile (<30 months), unreported gender, unreported breed, Bos taurus, bovine.

History: The bovine was presented for slaughter at a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) federally inspected slaughter facility and passed antemortem inspection. The carcass was retained for further diagnostic testing after lesions suspicious for bovine tuberculosis were observed in lymph nodes of the head, thoracic, and abdominal cavities and lungs during postmortem inspection.

Gross Pathology: None

Laboratory results: PCR from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were positive for IS6110 (Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex) and negative for IS900 (M. avium paratuberculosis) and 16S rDNA (M. avium complex). Culture recovered M. bovis.

Microscopic Description:

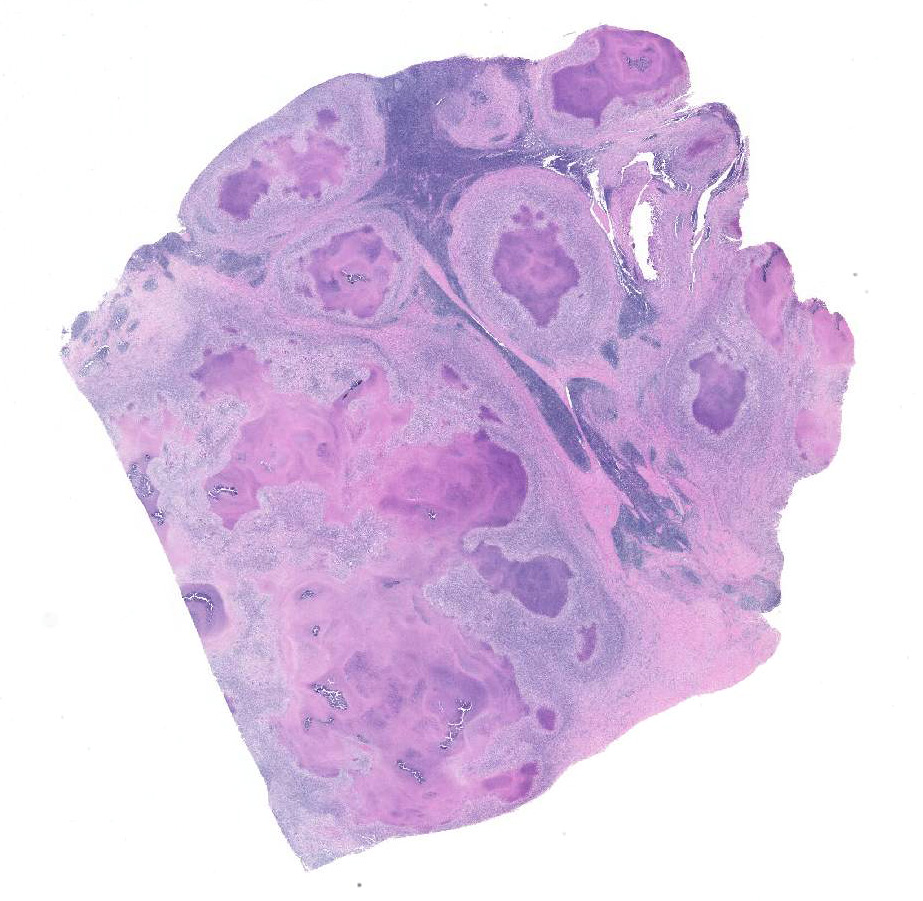

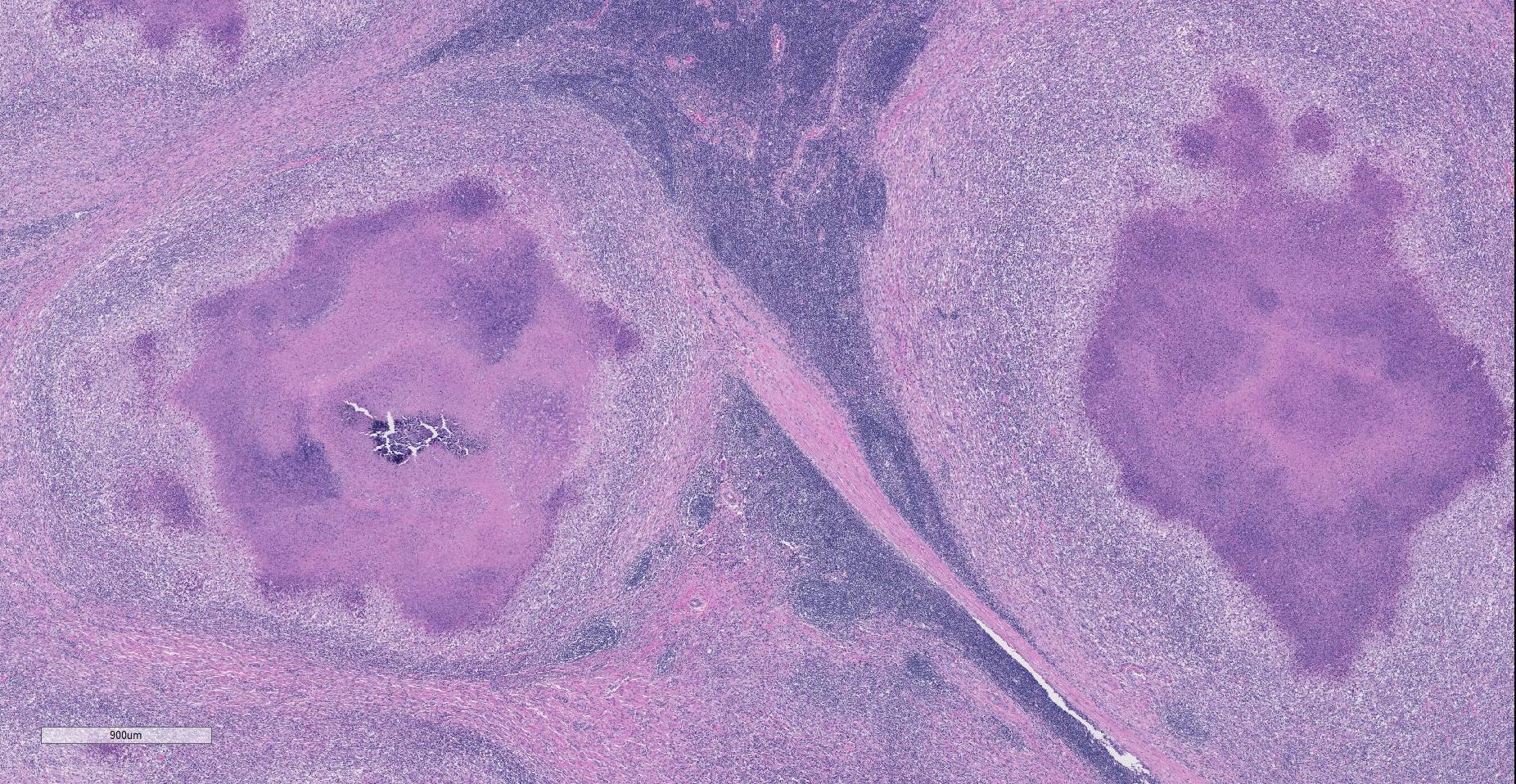

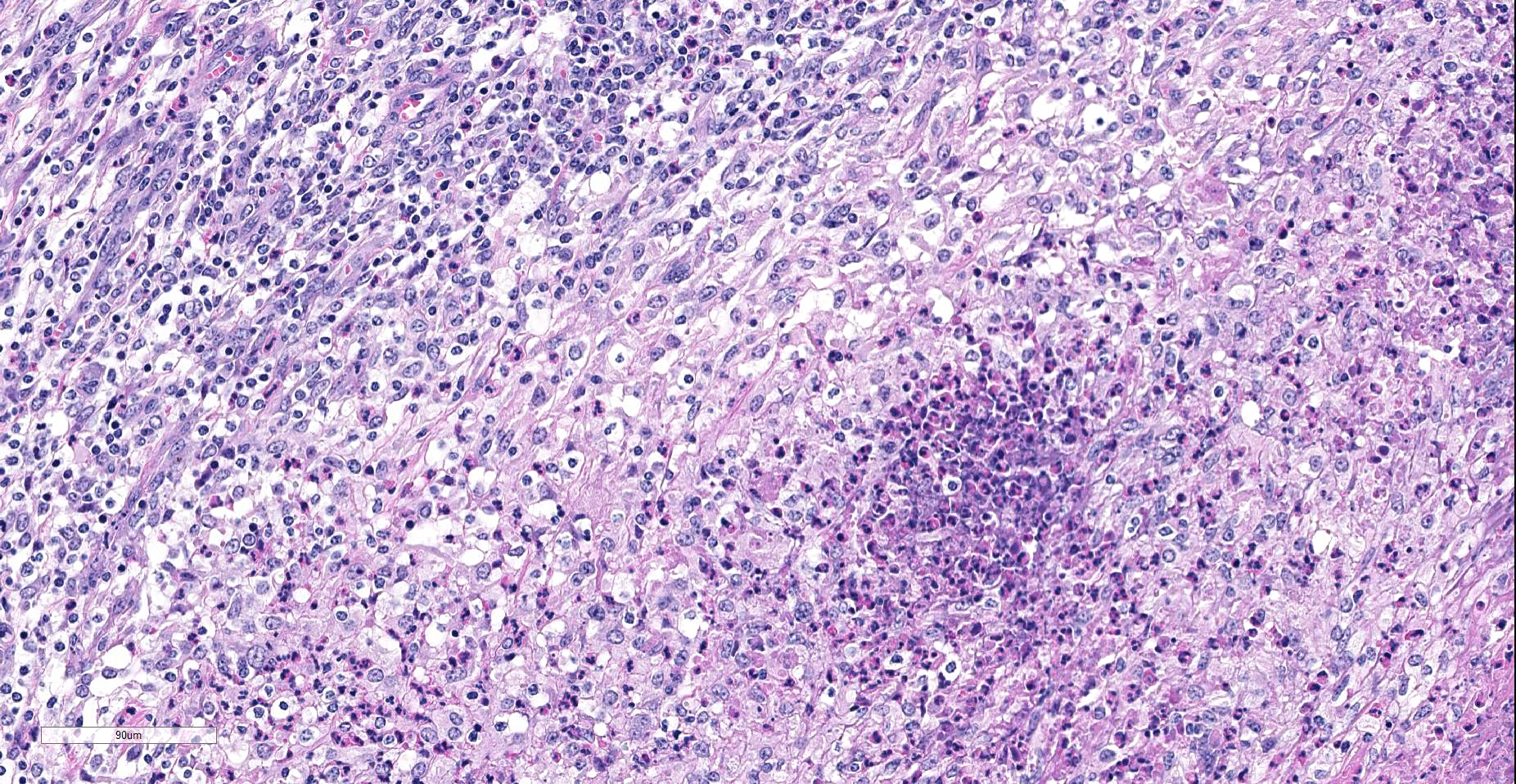

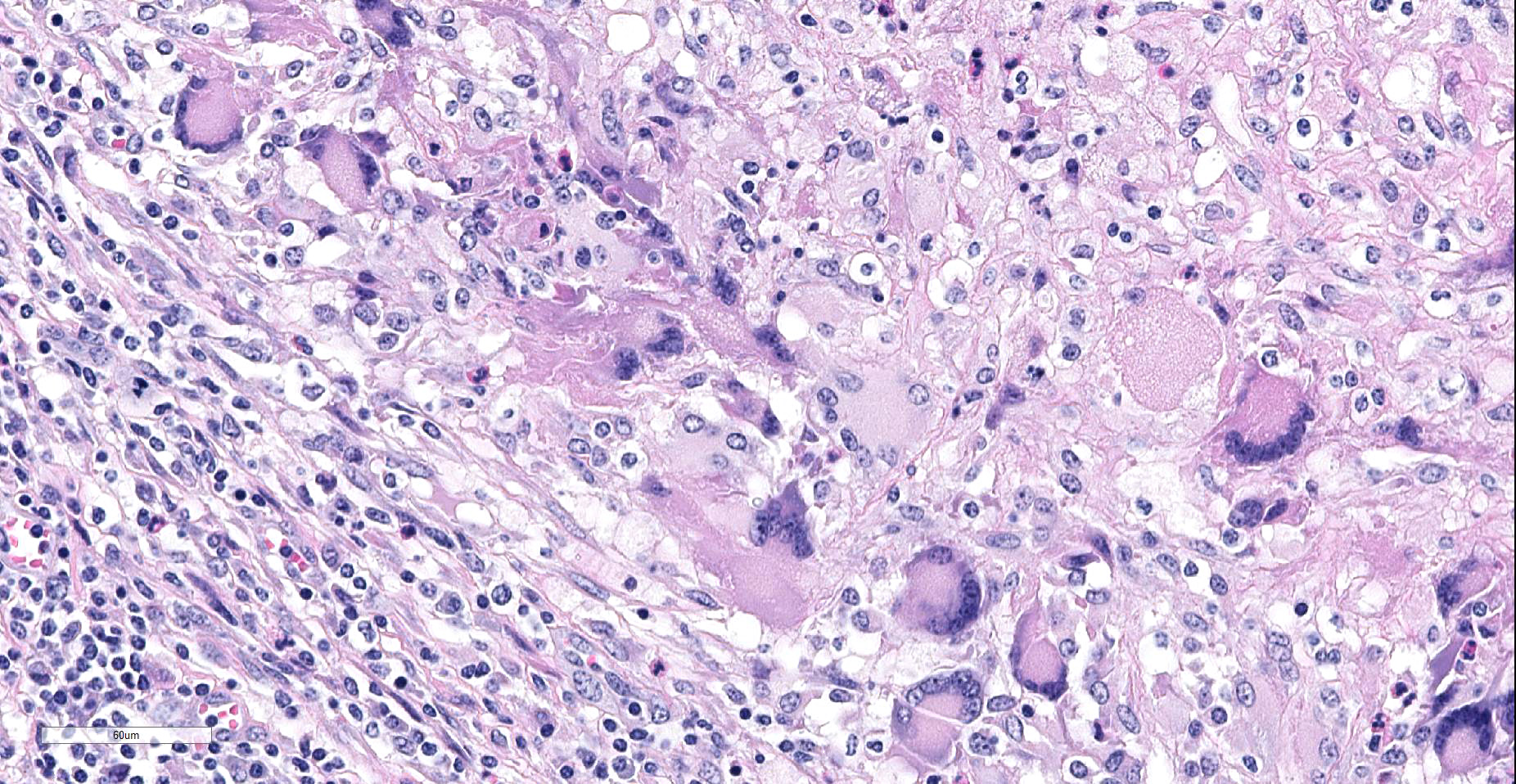

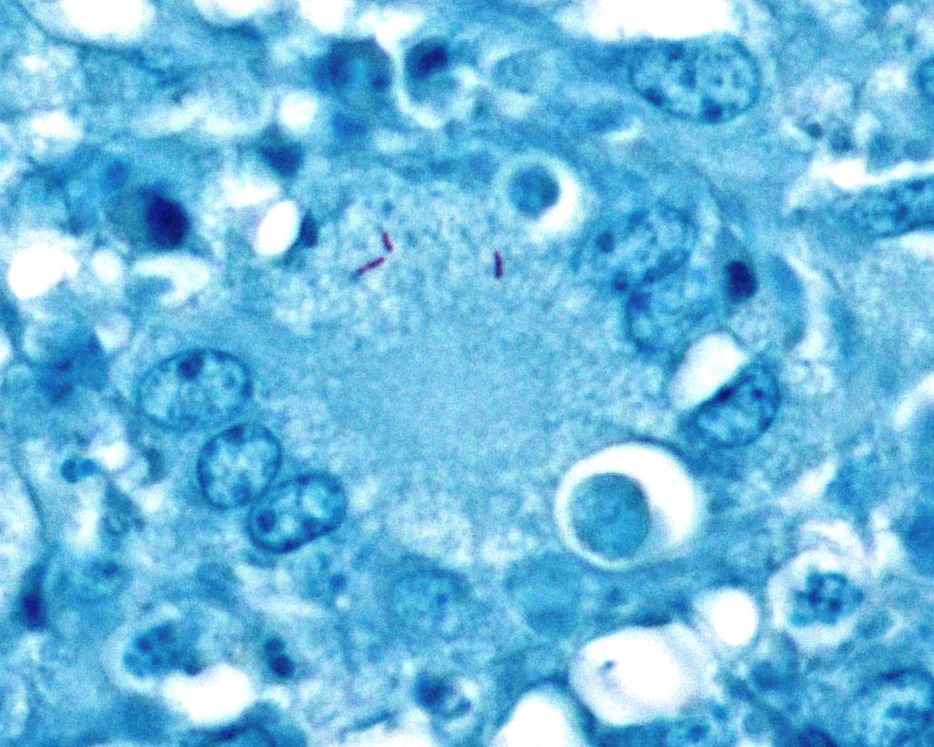

Lymph node. Up to 80% of the parenchyma (there is some slide variability) is effaced by coalescing to locally extensive granulomas. Granulomas are composed of central areas of caseous necrosis and variable amounts of basophilic granular material (mineral) rimmed by large numbers of epithelioid macrophages and multinucleated giant cells surrounded peripherally by lower numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, fibroblasts, and fibrous connective tissue. Giant cells have up to 10 peripheral nuclei (Langhans type). There are rare, ~5µm long, acid-fast bacilli within areas of necrosis and the cytoplasm of macrophages and giant cells.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Lymph node: Lymphadenitis, necrogranulomatous, locally extensive, chronic, severe, Bos taurus.

Contributor’s Comment: Mycobacterium bovis causes tuberculosis in many mammals, including cattle and is a zoonotic disease. Cattle slaughtered for consumption in the United States in federally inspected abattoirs undergo inspection by personnel from the Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS) of the USDA to insure they are safe and wholesome for entry into the market. In accordance with the USDA’s Bovine Tuberculosis Eradication Program, FSIS personnel retain carcasses when lesions resembling tuberculosis are identified. Suspect granulomas from these cattle are collected and submitted to the National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL) for histopathology and culture.8

Microscopic lesions consistent with tuberculosis in cattle are often multicentric and coalescing with central areas of caseous necrosis and mineral. Epithelioid macrophages with small to moderate numbers of Langhans-type multinucleated giant cells surround the necrosis with smaller numbers of peripheral lymphocytes, plasma cells, and occasional neutrophils. 2 The typical tuberculous lesion caused by Mycobacterium bovis has rare to occasionally moderate numbers of acid-fast bacteria present within the cytoplasm of macrophages and giant cells as well as in areas of necrosis 2

Bovine cases that are histologically compatible with tuberculosis undergo additional testing at NVSL by means of PCR on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue to test for mycobacterial DNA. Because the scope of the TB eradication program is focused on identifying M. bovis, primers used in the PCR are limited to those for M. tuberculosis complex (MTBC, of which M. bovis is a member), M. avium complex (MAC, common environmental mycobacteria) and M. avium paratuberculosis (MAP, the bacterium that causes Johne’s disease in cattle). A recent report7 of mycobacteria cultured from clinical samples submitted to the NVSL stated that the majority of mycobacteria cultured from cattle were M. bovis (32%) followed by M. avium complex (25.5%). The next most common species, M. fortuitum/M. fortuitum complex, comprised 10.1%.7

The microscopic features of the current case were consistent with bovine tuberculosis and FFPE tissue was tested by PCR for mycobacterial DNA using our primers for MTBC, MAC, and MAP. PCR was positive for the MTBC primer sets and negative for MAC and MAP. False negative results for mycobacterial DNA can occur in some cases. The more common reasons for false negative PCR results include tissue being fixed in formalin for an extended period of time (>7 days) and and/or extremely low numbers of AFB present in the lesion or tissue section. Formalin fixation causes irreversible cross-linking between DNA and protein, which becomes worse as the tissue fixes over time.3

Culture, which is considered the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis2 and can take up to 10 weeks to complete with slow-growing mycobacteria, recovered M. bovis.

Mycobacterium bovis is a member of the M. tuberculosis complex, which includes M. tuberculosis, M. africanum, M. canettii, M. pinnipedii, M. caprae, M. microti,5 and the newly described M. mungi.1 M. bovis can cause disease in cattle as well as humans and other domesticated and wild mammals. Currently, M. bovis is endemic in various populations of wildlife and are a source for re-infection of domesticated animals in regions of the United States (white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus), Spain (wild boar, Sus scrofa), United Kingdom (Eurasian badgers, Meles meles), and New Zealand (brushtail possums, Trichosurus vulpecula).6

Disease manifestation can vary, but M. bovis typically causes granulomatous inflammation in the lungs and lymph nodes of the head (retropharyngeal), chest (tracheobronchial and mediastinal) and/or abdomen (mesenteric), often reflecting the route of transmission (inhalation or ingestion).2,7 Grossly, the classic tubercle is encapsulated, pale yellow, and often has a caseous core that may be variably mineralized.2 Clinically, the only sign of infection may be chronic weight loss (wasting), weakness, loss of appetite, fluctuating fever, cough, exercise intolerance, and lymphadenomegaly.9 Most animals that are infected with M. bovis do not develop clinical disease.2

Contributing Institution:

National Centers for Animal Health, Ames, IA

http://www.ars.usda.gov/main/site_main.htm?modecode=36-25-30-00

http://www.aphis.usda.gov/nvsl

JPC Diagnosis: Lymph node: Lymphadenitis, granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with diffuse moderate follicular and paracortical hyperplasia.

JPC Comment: The contributor does an excellent job reviewing the thorough protocol used to investigate tissue suspected of Mycobacterium bovis infection at the National Veterinary Services Laboratory, an important link in food safety in the United States

M. bovis is a member of the growing M. tuberculosis complex as described above. A recent publication4 noted the divergent pathogeneses in non-bovine hosts in several countries of the world which have been incriminated in maintaining infection in local livestock.

In the North America, the white-tailed deer, and to a lesser extent, elk harbor the infection and potentiate the infection though contact with cattle in their pasturing area. Infected lymph nodes in deer often have soft centers, resembling abscesses; however neutrophils, as seen in cattle, are not a feature of the lesion. 4 Approximately 30-35% of infections exhibit spread to the thoracic viscera, and often the pleural surfaces, where they form pearlescent nodules reminiscent of mesothelioma.

In England and Ireland, the Eurasian badger (Meles meles) has been indicted as a major factor in outbreaks of cattle with bovine tuberculosis. In the badger, respiratory infection is most common with 50% cases showing pulmonary infection, and 35% of cases involving lymph nodes. Elongate radial lesions may be seen in the kidneys, and miliary lesions may be seen in the liver and spleen. Many infected badgers show no visible gross lesions.4

In western Europe, wild boars serve as wildlife reservoirs of Mycobacterium bovis. This species, well known as highly susceptible to M. bovis, has been used as a sentinel species to screen for M. bovis in Hawaii and New Zealand. Disseminated infection is the rule in this species, with lesions in multiple anatomic regions, including cranial lymph nodes and mandibular lymph nodes, lungs, liver, and spleen.4

In New Zealand, the brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) is considered a source of infection for cattle. Highly susceptible, they manifest the disease by infection of subcutaneous lymph nodes, forming draining fistulous tracts. Terminally ill possums attract cattle by wandering erratically across pastures, and curious cattle may sniff and lick them, thereby receiving exposure to the bacteria. In these regions, infected wild ferrets may also be infected, but their role in spreading the infection to cattle is controversial – a reduction in possum population in these areas results in a proportional decrease in infection of this carnivore, suggesting that the ferret is a spillover host at best.4

The participants agreed that an alternate JPC diagnosis of multiple lymph node granulomas would be acceptable as well. As this was the last conference of the 2018-2019 year, the box containing the age-old discussion of “granulomatous versus granuloma” was quickly slammed shut.

References:

- Alexander KA, Laver PN, Michel AL, Williams M, van Helden PD, Warren RM, Gey van Pittius NC: Novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex pathogen, M. mungi. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 1296-1299, 2010

- Caswell JL, Williams KJ: Respiratory system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, pp. 523-653. Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, 2007

- Fang SG, Wan QH, Fujihara N: Formalin removal from archival tissue by critical point drying. Biotechniques 33: 604-611, 2002

- Fitzgerald SD and Kaneene JB. Wildlife reservoirs of bovine tuberculosis worldwide: hosts, pathology, surveillance, and control. Vet Pathol 2013; 50(3):488-499.

- Olsen I, Barletta RG, Thoen CO: Mycobacterium. In: Pathogenesis of Bacterial Infections in Animals, pp. 113-132. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010

- Palmer MV, Thacker TC, Waters WR, Gortázar C, Corner LAL: Mycobacterium bovis: A model pathogen at the interface of livestock, wildlife, and humans. Vet Med Int 2012: 17, 2012

- Palmer MV, Waters WR: Advances in bovine tuberculosis diagnosis and pathogenesis: What policy makers need to know. Vet Microbiol 112: 181-190, 2006

- Thacker T, Robbe-Austerman S, Harris B, Palmer MV, Waters WR: Isolation of mycobacteria from clinical samples collected in the United States from 2004 to 2011. BMC Vet Res 9:100, 2013

- Thoen CO: Overview of tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infections. In: The Merck Veterinary Manual Online, eds. Aiello SE, Moses MA. 2012