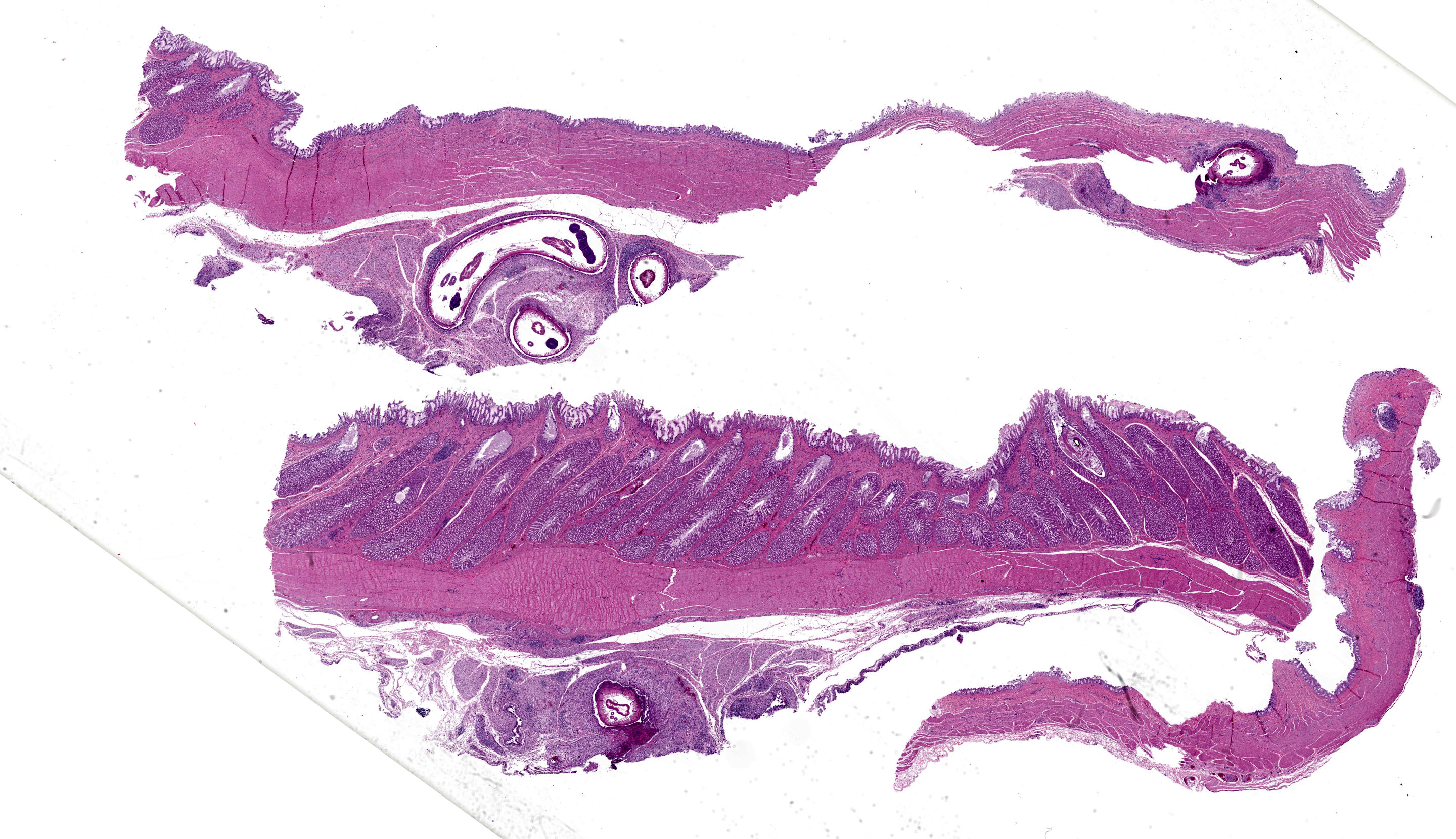

Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 19, Case 3

Signalment:

Adult great blue heron (Ardea herodias) of unknown sex

History:

The free-ranging heron was found dead on zoo premises. Blood was noted on the feet.

Gross Pathology:

The heron was in markedly autolyzed post-mortem and mildly decreased nutritional condition. Scant dried blood coated the feet. Intracoelomic and pulmonary hemorrhage were present. Embedded in the proventricular and ventricular serosa were seven, 1 mm diameter and 6-11 cm long, tan and red nematodes with tapered tails. A gill raker fragment was firmly embedded in the proventricular mucosa. Firm, cylindrical concretions of feces filled the colon and cloaca.

Laboratory Results:

Cloacal and oropharyngeal swabs were submitted for highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAIV) PCR test. HPAIV was not detected in the sample.

Microscopic Description:

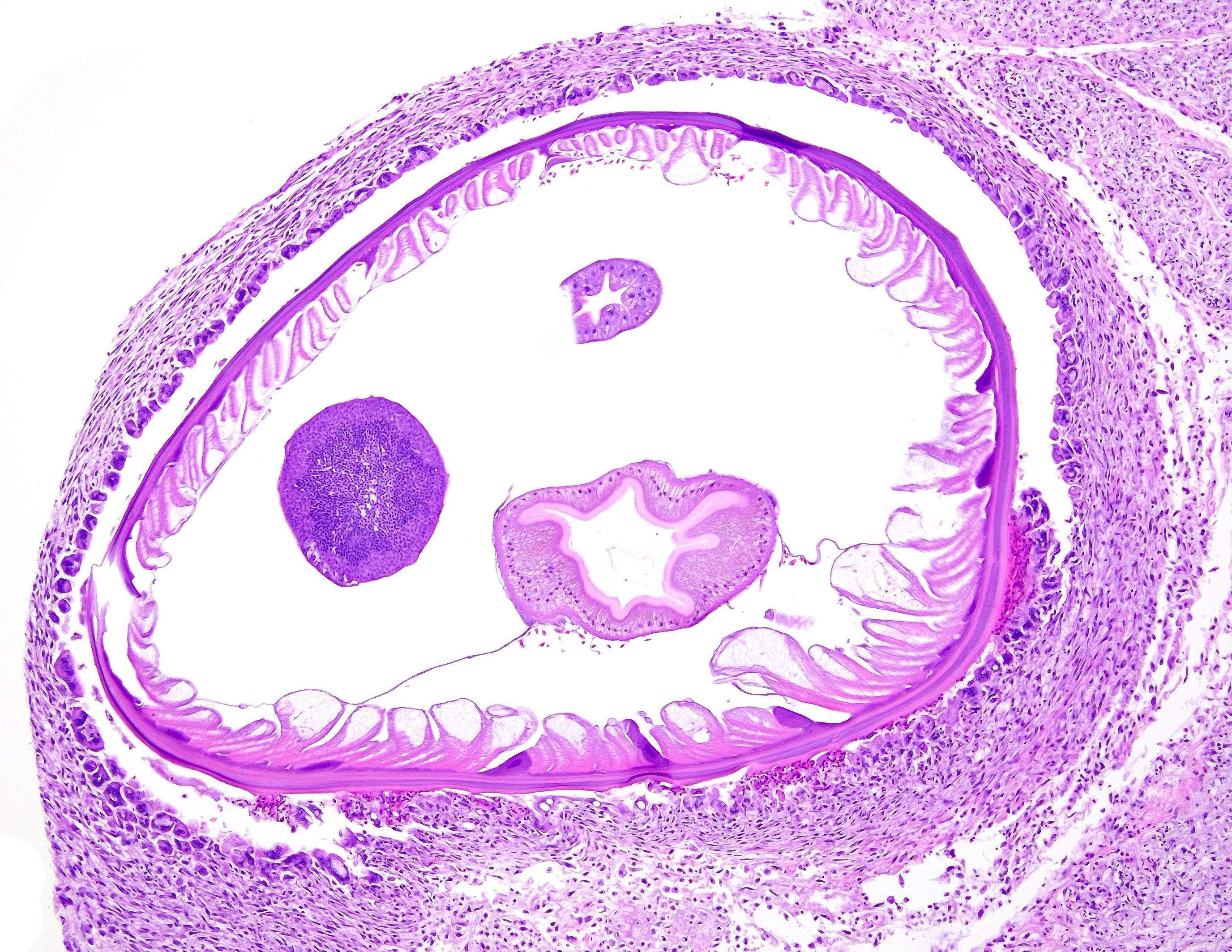

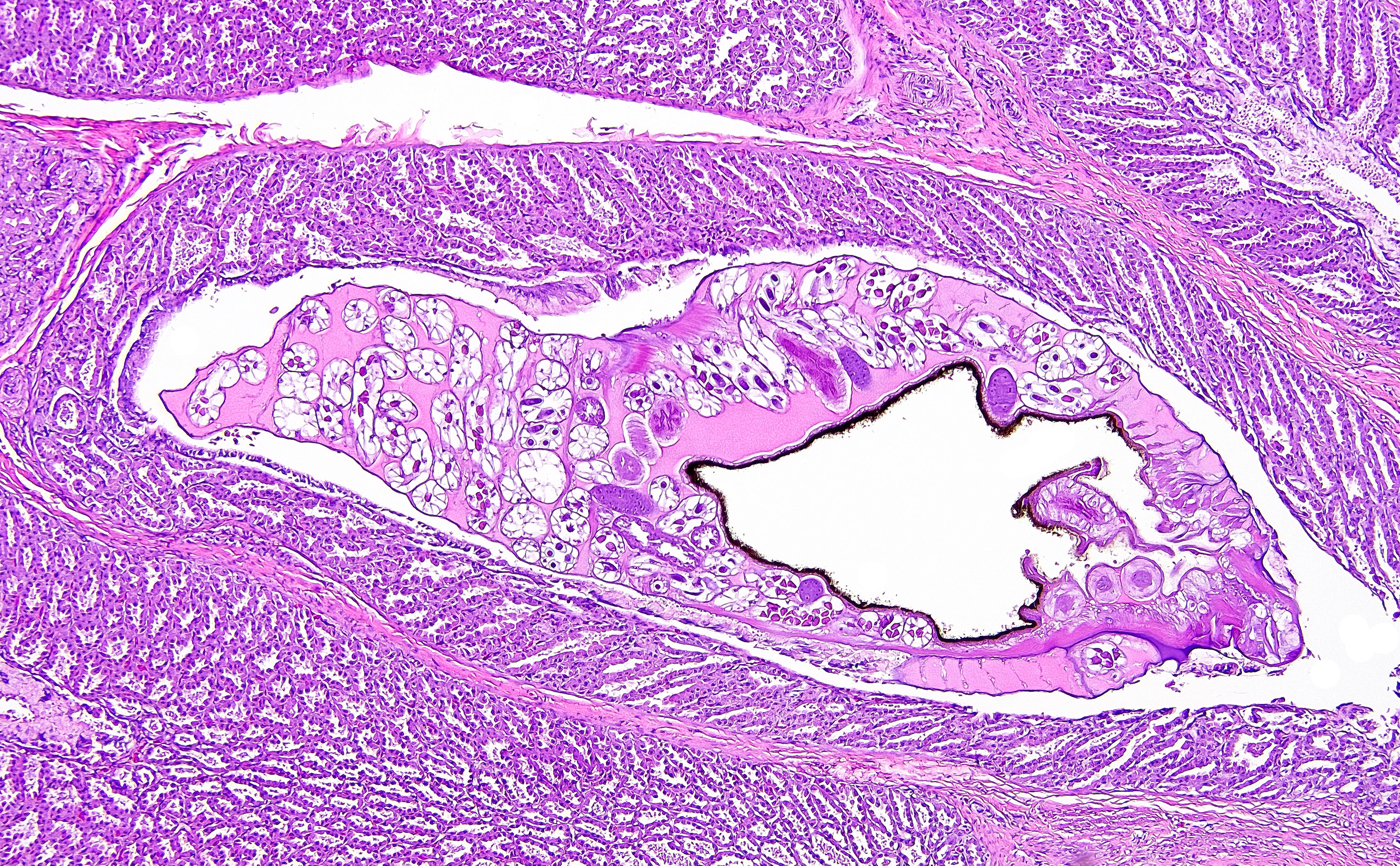

Proventriculus (1 section): The serosa and adjacent adipose are focally disrupted and expanded by a 2.5 mm-diameter granuloma centered on a single, 1 mm-diameter adult nematode that has a smooth eosinophilic cuticle, polymyarian-coelomyarian musculature, hypodermal nuclei, ventral nerve cords, a pseudocoelom, a glandular esophagus with associated pseudomembranes, a reproductive tract, and an intestinal tract lined by uninucleate, columnar epithelium with a prominent brush border (aphasmid). The nematode is surrounded by large numbers of fragmented heterophils, epithelioid macrophages, and multinucleated giant cells. The granuloma is circumscribed by concentric layers of loose fibrous connective tissue interspersed with many plump fibroblasts and small numbers of lymphocytes. The serosal vessels are multifocally cuffed by medium numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The adipose tissue is severely atrophied. A single proventricular gland is distended by an intraluminal, 0.5 x 1.5 mm adult nematode that has a smooth thin eosinophilic cuticle, indistinct musculature, a pseudocoelom filled with eosinophilic homogeneous material, a reproductive tract containing many embryonated eggs, and an intestinal tract lined by uninucleate columnar epithelium (spirurid). The eggs are 20 x 30 um and ovoid with a smooth, thick shell. Remaining glands multifocally contain eosinophilic flocculent material. The overlying lamina propria is infiltrated by small numbers of eosinophils.

Ventriculus (2 sections): The muscularis and serosa are multifocally disrupted by large, multifocal to coalescing granulomas centered on four sections of an adult aphasmid nematode similar to that previously described in the proventriculus. The granulomas are similarly circumscribed by fibrous connective tissue interspersed with medium numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. The adjacent adipose is severely atrophied.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Proventriculus and ventriculus: Severe, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, granulomatous proventricular serositis and mural ventriculitis with adult aphasmid nematodes

Proventriculus: Moderate, focal glandular ectasia with intraglandular adult spirurid nematode and mild eosinophilic proventriculitis

Contributor’s Comment:

Eustrongylidosis is a condition of fish-eating birds caused by infection with aphasmid nematodes in the genus Eustrongylides, which has 3 recognized species E. ignotus, E. tubifex, and E. excisus.5 Eustrongylides spp. are found globally, except for arctic and subarctic regions, and E. ignotus and E. tubifex are the two species most often reported in the USA. 1,5 Classically, E. ignotus affects the ventriculus of Ciconiiformes, whereas E. tubifex affects the esophagus and proventriculus of mergansers, loons, and cormorants.1,2

For E. ignotus, the definitive hosts are multiple genera of herons and egrets in the family Ardeidae.10 Intermediate hosts include a variety of fish species and oligochaete worms.2,9 Birds shed eggs into the environment via their feces, and eggs are consumed by the first intermediate host, an oligochaete worm.1,5 First and second stage larvae mature within the worm.5 The first intermediate hosts are then ingested by fish and larvae migrate through the body after penetrating the intestinal wall. Within the fish, larvae mature to the third and fourth stages and can be found in muscle, hepatopancreas, and gonads.5 Amphibians, reptiles, and predatory fish can also serve as paratenic hosts.1 Birds then consume parasitized fish or other paratenic hosts and infective fourth stage Eustrongylides larvae reach the stomach wall within 3-5 hours of ingestion.5 Larvae mature over the next 10-15 days, and start producing eggs between 10-25 days post ingestion.1,5 Eggs are excreted into the environment, where they can survive for several years. 5 Non-patent infections with E. ignotus have been reported in Pelecaniformes and non-ardeid Ciconiiforme birds, and birds of prey can also be parasitized.1,10

The prevalence of Eustrongylides spp. varies between studies and may be related to regional variation in parasite prevalence, increased prevalence in birds submitted to rehabilitation centers or for necropsy, age group studied, and affected avian species. One study in birds at a North California wildlife rehabilitation center found Eustrongylides sp. in 30% of necropsied herons and egrets.6 An earlier study found only 6% of wild nestlings collected from a colony in Northern California were infected, compared to 4% of nestlings in a Rhode Island colony and 35% in a Texas colony.3

In affected herons and egrets, low burdens are typically subclinical whereas higher parasite burdens can contribute to individual morbidity and mortality, especially in younger birds.6 Associated clinical signs include hypothermia, anorexia, regurgitation, weakness, and weight loss.6,10 Multiple epizootics have been reported in wild Ardeidae, especially in nestlings in coastal rookeries.1,9 Fatal cases are associated with severe coelomitis and sepsis when penetration of the ventriculus wall by larval eustrongylids leads to bacterial translocation.2,9

Acute lesions are found in birds as young as 2 days, as well as adults, and are most often associated with fourth-stage larvae, with rarer non-gravid adults.9 Parasites are typically found below the serosa of the ventricle or on the ventral aspect of the serosal surface.9 Less often, parasites and/or associated lesions can be found in the air sacs, liver, pericardium, body wall, intestine, or other caudal coelomic organs.9 Chronic lesions occur in birds over 1 week old, and the majority involve adult parasites.9 Tortuous, yellow-tan, tubular tunnels containing tan to red nematodes extend across the ventriculus surface, sometimes extending to the intestines and liver.6,9 Air sacs, gallbladder, proventriculus, cloaca, body wall, and pancreas are less often involved, with esophagus, spleen, kidney and lung rarely affected.9 More chronic and/or severe cases can have coelomitis, air sacculitis, fibrinous and fibrous adhesions, and inflammatory nodules in multiple organs.9 For both acute and chronic cases, a subset are associated with subserosal hematomas.9

The most common microscopic findings in acute cases are parasite larvae associated with minimal hemorrhage, eosinophilic inflammation, and pyknotic cellular debris.9 With chronicity, changes include granulomatous inflammation, necrosis, and fibrosis accompanied by bacterial colonies and eustrongylid eggs. 9 Fibrinous to fibrous tunnels connect to the ventriculus lumen and contain a single, adult parasite, with variable intramural mineralization, eosinophilic infiltrates, and bacteria.9 Aphasmid nematodes are distinguished by bacillary bands and a single genital tract in adult females.4 Eustrongylides spp. have thick-shelled, operculated eggs, a glandular esophagus, a smooth cuticle, coelomyarian musculature, and pseudomembranes.4

In waterbirds, a specific coelomic palpation protocol is a useful antemortem diagnostic technique, especially for more chronic cases with tunnel lesions.8 Mineralization of parasite tunnels in the ventriculus may be visible radiographically.10 Post-mortem diagnosis is typically by observation of characteristic lesions and identification of larvae or adult parasites, although molecular-genetic techniques are also reported.5 Human eustrongylidosis is rare, reported most often in the USA in individuals with a history of ingesting live or raw fish.5

Tetrameres spp. are spirurid nematodes belonging to the Tetrameridae family, a group which includes three genera (Tetrameres, Microtetrameres, and Geopetitia) and dozens of species.2,7 For Tetrameres, female parasites are found within proventriculus glands; males are either associated with females or within the lumen, although some species encyst within the muscular wall.7 Sexual dimorphism is a prominent feature for Tetrameridae and females may be globular and less filiform than males due to marked uterine distention.7 Tetrameres lifecycles vary based on species, but the definitive host is usually an aquatic bird and the intermediate host is usually a crustacean.7 For parasites primarily affecting terrestrial birds, the intermediate host are typically orthopteran or coleopteran insects.7 Prevalence varies based on species and geographic location; prevalence and intensity can also vary substantially by year and study.7 Infection is often considered incidental, but overcrowding and high intensity infections can contribute to morbidity and/or mortality.2 In domestic species, typical clinical signs of Tetrameres sp. infection include hyporexia, diarrhea, and emaciation, and clinical signs in wild birds are less defined.7 Aquatic birds are most often affected (e.g. Anseriformes, Ardeiformes, Gruiformes, and Charadriiformes), although Passeriformes and Galliformes can be parasitized by some species.7 Microtetrameres spp. more often parasitize terrestrial birds or those feeding on land, whereas Geopetitia can parasitize a wide variety of wild birds globally.7 For this case, Microtetrameres sp. remains a differential based on histologic features. Classic gross findings of Tetrameres sp. infection include red nodules in the proventricular mucosa containing red, female adult worms, which can be visible from the serosal surface, mucosal hyperplasia, necrotic material coating the proventricular mucosa, mucoid material coating the small intestinal mucosa, and green to golden-brown discoloration of small intestinal contents.2,7 Histologically, parasites show typical features of spirurid parasites including coelomyarian musculature, large intestines lined by uninucleate cells, eosinophilic fluid within the pseudocoelom, prominent lateral chords, and small characteristic spirurid eggs within adult females.4 Proventricular glands are distended by adult female nematodes, which can cause compressive changes in adjacent tissue, and there is variable mucosal inflammation.7 Fecal examination may reveal ovoid, thick-shelled, larvated ova; however, these are challenging to differentiate from other spirurid eggs.7 Typically, diagnosis is via post-mortem detection of classic lesions and worms, and speciation is primarily via examination of male worms.7 Tetrameres spp. can infect both domestic and wild birds, but is not known to infect humans.7

Contributing Institution:

University of Wisconsin

School of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Pathobiological Sciences

2015 Linden Drive

Madison, WI 53706

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Proventriculus and ventriculus: Serositis, granulomatous, diffuse, marked with adult aphasmid nematodes

2. Proventriculus: Glandular ectasia, focal, moderate to marked, with intraglandular adult spirurid nematode

3. Adipose tissue: Atrophy, diffuse, marked

JPC Comment:

We thank the contributor for the detailed writeup and presentation of these two nematodes in section. Identifying Eustrongylides was not much of a diagnostic mystery as characteristic structures were easy to appreciate (and its large size helps a bit as well). The single Tetrameres was slightly more problematic though careful examination and comparison to Eustrongylides allowed conference participants to appreciate the different features. The eosinophilic fluid within the pseudocoelom was helpful as the overall shape of the nematode is not as globoid (or filled with ova) as we have seen previously which may reflect some degeneration. Incidentally, we also noticed the eosinophils the contributor describes in the adjacent portion of the proventriculus. Distinguishing granulocytes is difficult in birds, though the round granules (and adjacent metazoan parasite) are supportive. In contrast, heterophils have more elongate granules. We also added an additional morphologic diagnosis for the atrophy of fat which was quite pronounced in this case.

References:

- Eustrongylidosis. In: Friend M, Franson JC, eds.?Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases: General Field Procedures and Diseases of Birds. US Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division. 1999; 223-228.

- Fenton H, McManamon R, Howerth EW. Anseriformes, Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, and Gruiformes.?In: Terio KA, McAloose D, St Leger J eds. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. Associated Press; 2019.

- Franson JC, Custer TW. Prevalence of eustrongylidosis in wading birds from colonies in California, Texas, and Rhode Island, USA. Col Waterbirds. 1994;17(2):168-172.

- Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. In: An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1999.

- Honcharoy SL, Soroka NM, Galat MV, Zhurenko OV, Dubovyi AI, Dzhmil VI. Eustrongylides (Nematoda: Dioctophymatidae): Epizootiology and special characteristics of the development biology. Helminthologia. 2022;59(2):127-142.

- Horgan M, Duerr R. Gross pathology of herons and egrets (family Ardeidae) at a wildlife rehabilitation centre in Northern California. J Wildl Rehabil. 2021;37(1):29-41.

- Kinsella JM, Forrester DJ. Tetrameridosis. In: Atkinson CT, Thomas NJ, Hunter DB, eds. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds. John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

- Spalding MG. Antemortem diagnosis of eustrongylidosis in wading birds (Ciconiiformes). Col Waterbirds. 1990;13(1):75-77.

- Spalding MG, Bancroft GT, Forrester DJ. The epizootiology of eustrongylidosis in wading birds (Ciconiiformes) in Florida. J Wildl Dis. 1993;29(2):237-249.

- Spalding MG, Forrester DJ. Pathogenesis of Eustrongylides ignotus (Nematoda: Dioctophymatoidea) in Ciconiiformes. J Wildl Dis. 1993;29(2):250-260.