CASE II:

Signalment:

11-years-old, female, Miniature schnauzer, dog (Canis familiaris)

History:

The dog presented with subcutaneous mass in left submandibular area. The mass was resected, and submitted to pathological examination.

Gross Pathology:

The mass was solid. The cut surface of the mass was solid and firm, and brown-gray in color. The mass was considered as the mandibular gland because of the location adjacent to the parotid gland.

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory findings reported.

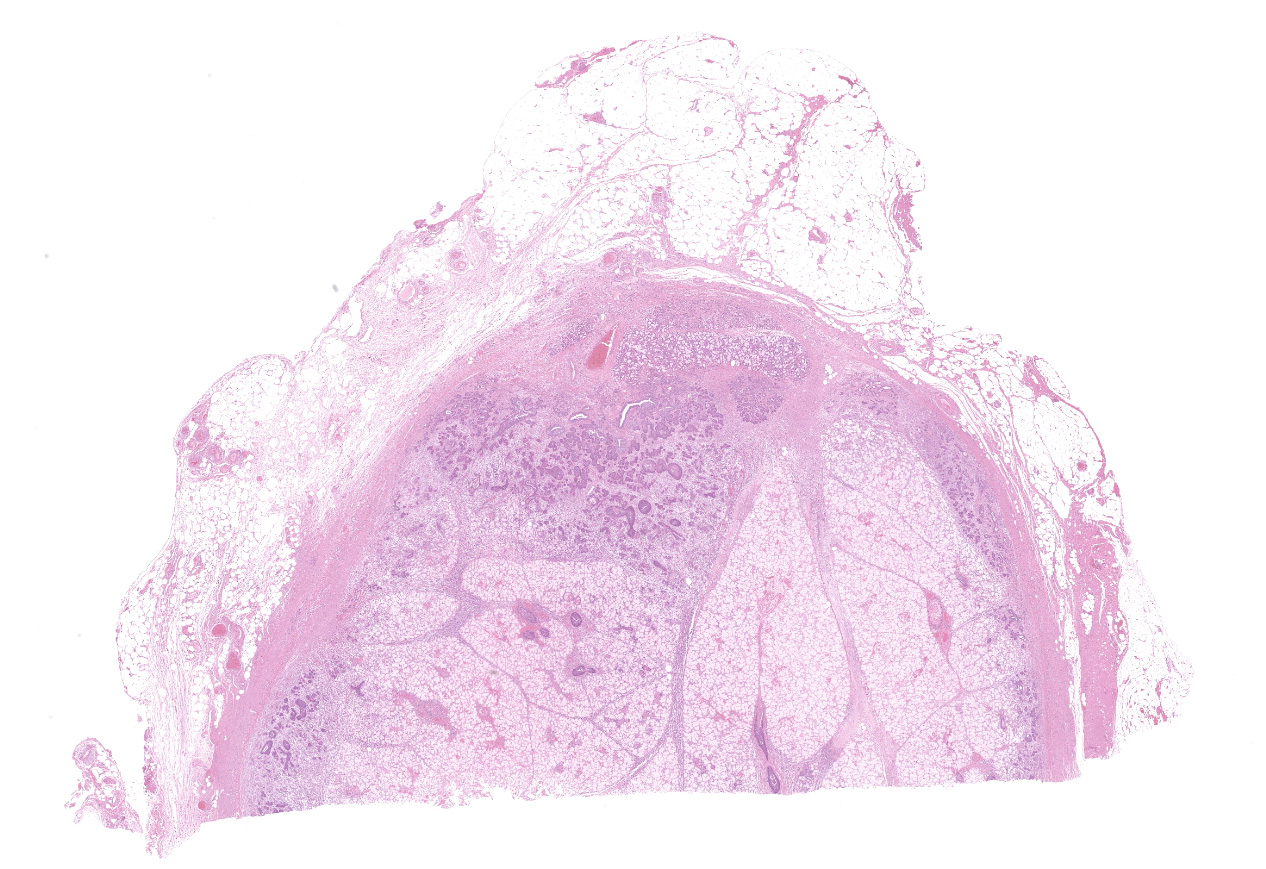

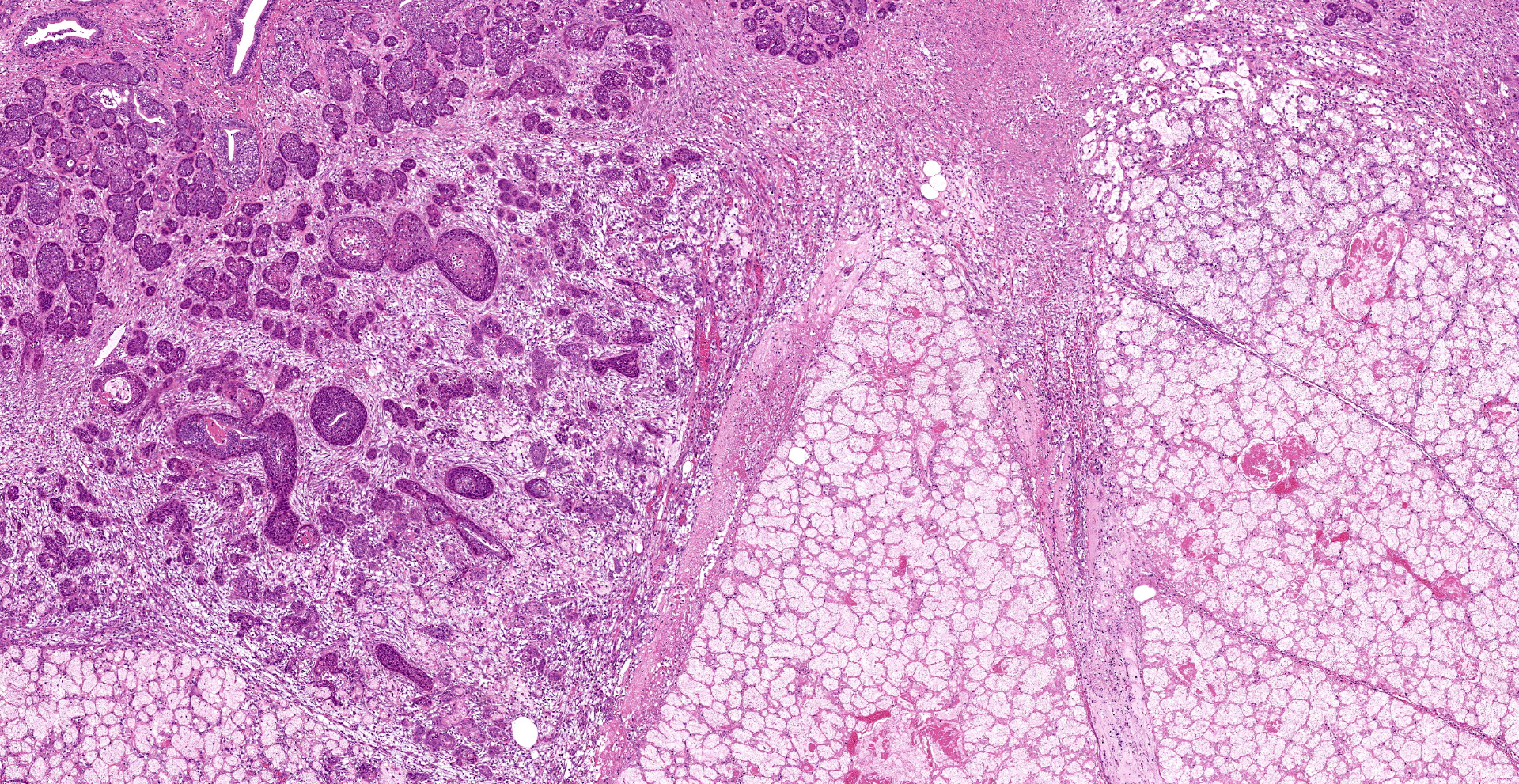

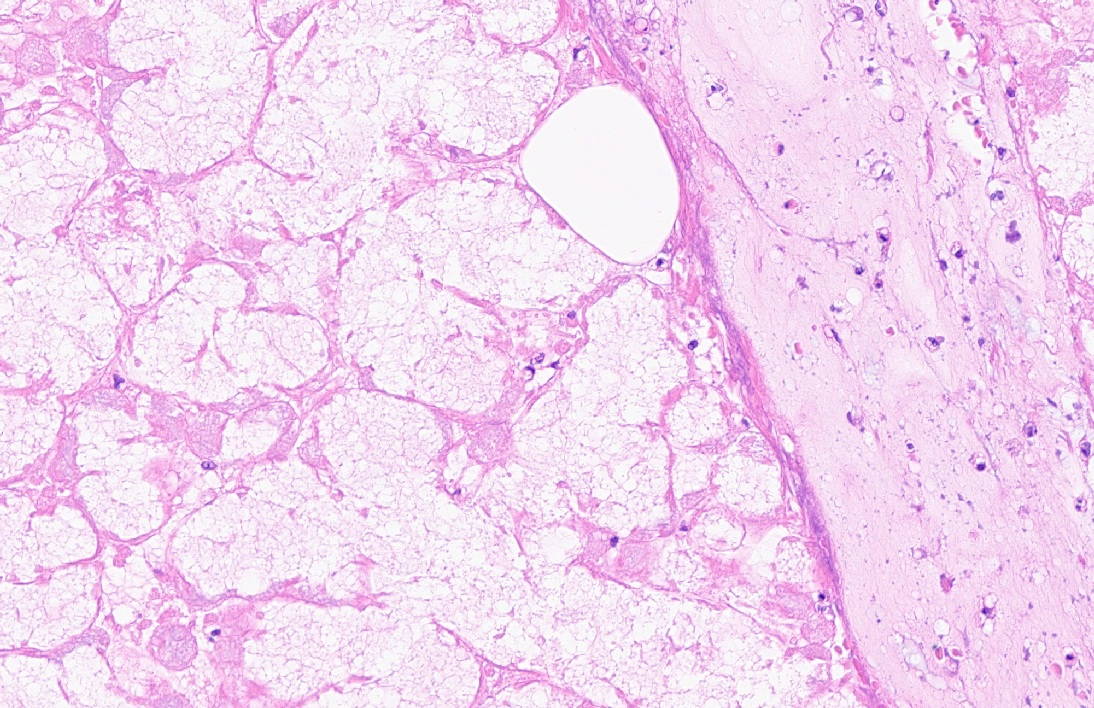

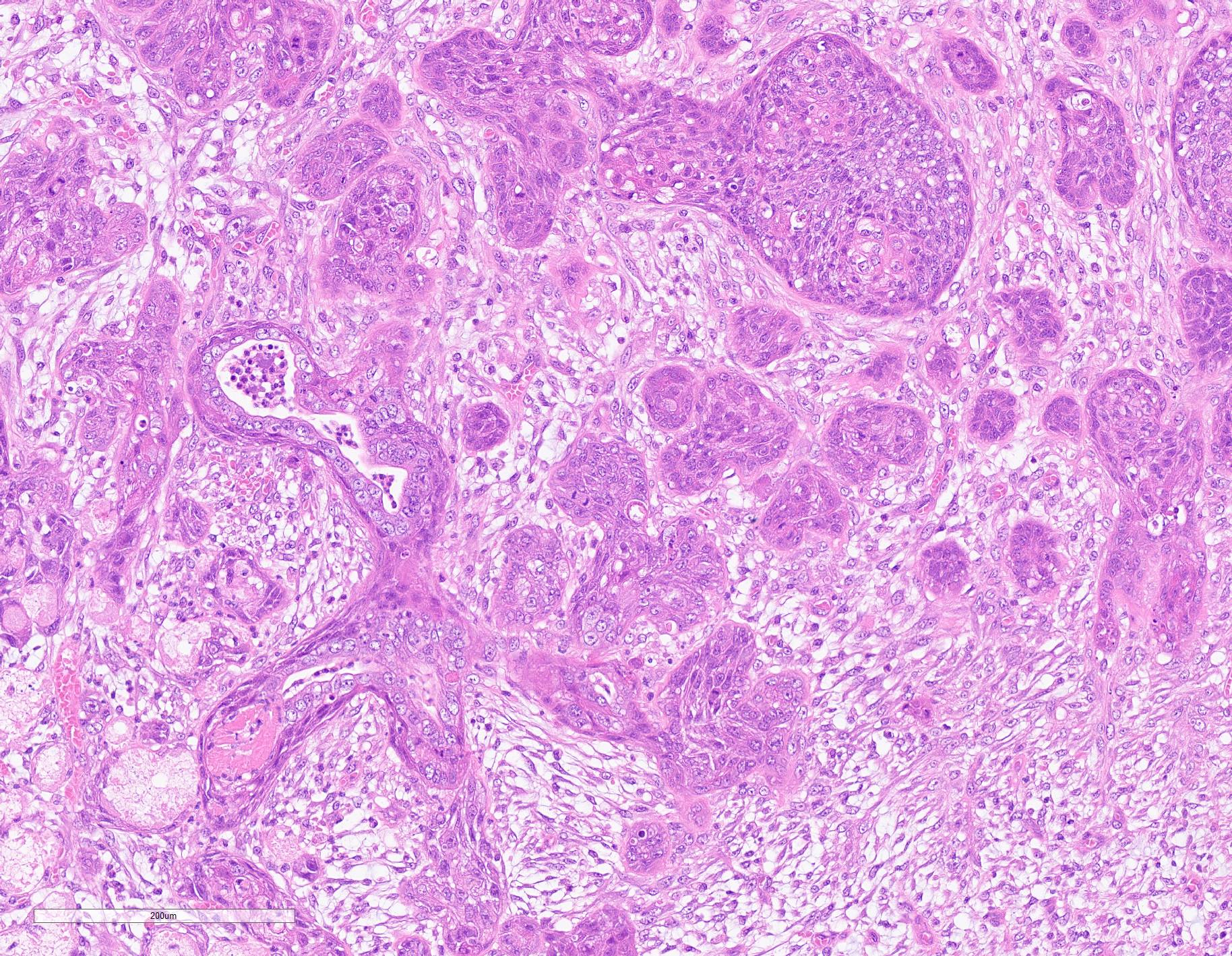

Microscopic Description:

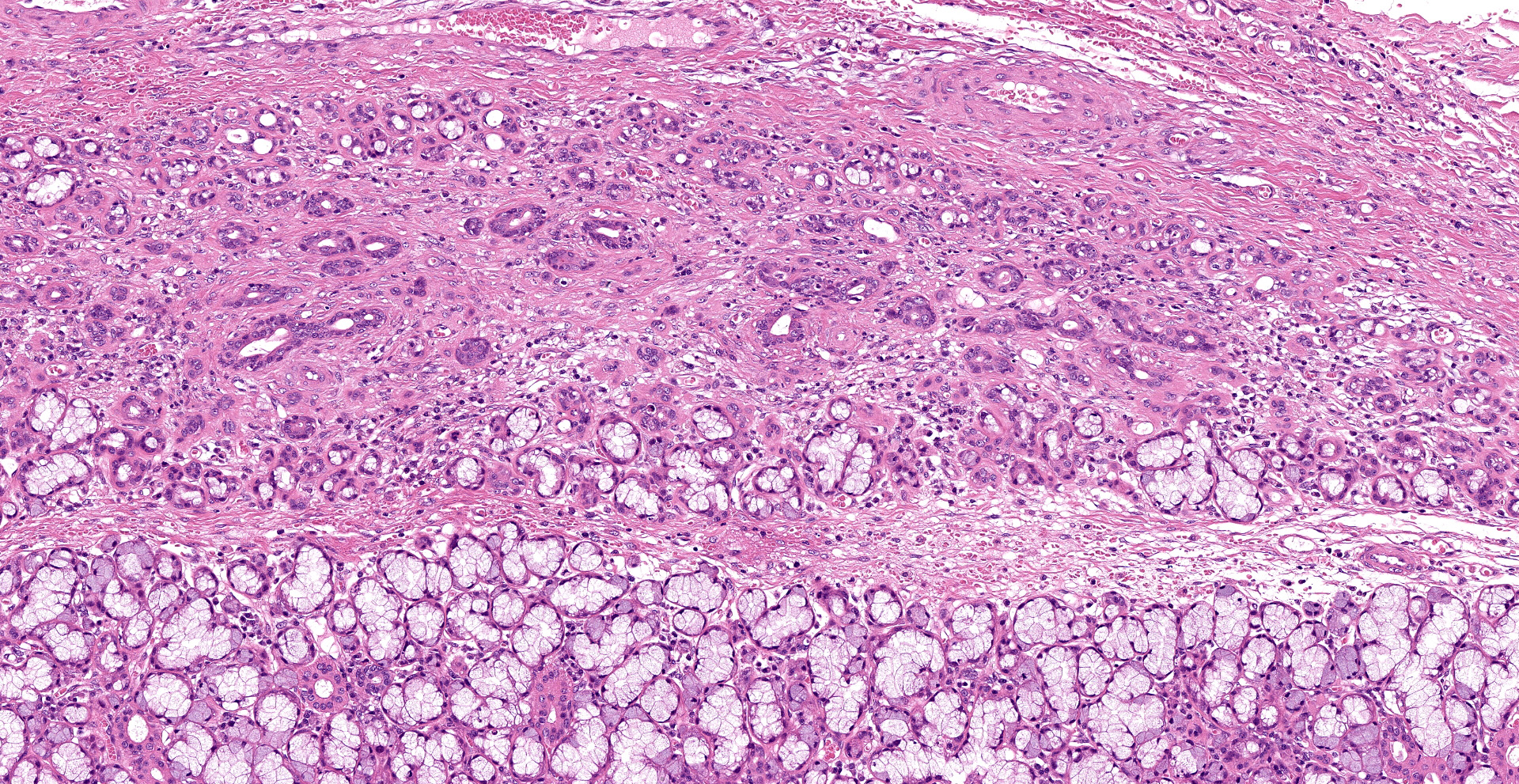

Extensive coagulative necrosis of the mandibular gland was observed with presentation of the lobular architecture. There was thrombosis of small and large vessels in the necrotic areas. The affected lobule of the mandibular gland was surrounded by thick fibrous capsule. In the peripheral area of lobule beneath fibrous capsule, there was ductal hyperplasia and squamous metaplasia of ductal epithelium with edema, hemorrhage and inflammatory cell infiltration. The hyperplastic ducts sometimes reached to fibular capsule. Ductal epithelium had vesicular nuclei with mild anisokaryosis and small number of mitoses, but no plemorphism or atypia. Hyperplastic ducts were lined by basement membranes and did not show any invasion to surrounding tissues. In the parotid gland adjacent to the mandibular gland, there was slight enlargement of ducts, however no necrosis or other histological abnormalities were found.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Necrotizing sialometaplasia.

Contributor's Comment:

Necrotizing sialometaplasia (NS) is rarely reported in animal, although naturally occurring cases have been reported in dogs and cats, in addition to one spontaneous case in rabbit and one experimentally induced case in a rat.1,3,5,7 NS has been reported to account for 6% (9/160) of canine salivary gland diseases and most cases were seen in small breed dogs, primarily terriers. NS most commonly affects the mandibular gland in dogs, although the parotid salivary gland was reported to be affected in one case.3,5 Any salivary gland may be affected In humans; most cases have been reported in the oral cavity, commonly at the junction of hard and soft plates.9

The exact etiology and pathogenesis NS is not known. The causes are thought to be vascular injury, type III hypersensitivity, Bartonella spp. infection, or immune mediated vasculitis.3,5,7 The most widely accepted theory explaining the etiology of NS is injury of the blood vessels, leading to ischemic and infarction of the salivary gland acini. It is unclear if the dog in this case had traumatic vascular injury, as vasculitis is not observed in the examined tissue sections.

The main histological features of NS observed in this case include extensive coagulative necrosis of salivary tissue, vasculopathy including vascular thrombosis and/or fibrinoid degeneration, squamous metaplasia of ducts and acini, and variable inflammation and fibrosis. These features are easily and often misinterpreted as malignant transformation. Hyperplastic ductal elements and squamous metaplasia are often mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. Some characteristics used to distinguish NS from squamous cell carcinoma include preservation of the general lobular structure of salivary gland and absence of atypical nuclei in the metaplastic squamous epithelium. Fibrinoid necrosis of arteries was not observed on our case, however, the histological features were identical to the characteristics of NS and sufficient to diagnose as NS.

Contributing Institution:

Laboratory of Pathology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Setsunan University,

45-1 Nagaotohge-cho, Hirakata, Osaka 573-0101, Japan

JPC Diagnosis:

Salivary gland, submandibular: Coagulative necrosis (infarct), focally extensive, with ductular degeneration, necrosis, and regeneration, and acinar atrophy.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a concise review of a unique lesion frequently mistaken for a neoplastic process by neophyte pathologists.

A recent retrospective study of salivary gland diseases in 179 dogs found only 2.2% of salivary glands submitted to be consistent with necrotizing sialometaplasia. In contrast, the most common diagnosis was non-specific sialoadenitis (49.7%), followed non-pathologic changes (23.4%), neoplasia (20.1%), and lipomatosis (3.9%). Nearly 70% of the lesions noted in this case series affected a major extraoral salivary gland, with the mandibular salivary gland being the most common.4

In regard to neoplastic disease, 88.8% of neoplasms were epithelial, followed by round cell (5.5%), carcinosarcoma (2.7%), and undetermined (2.7%). Of the 36 epithelial neoplasms, the most common type was adenocarcinoma (14/36), followed by mucoepidermoid carcinoma (10/36), acinic cell carcinoma (7/36), and squamous cell carcinoma (1/36). Lipomatosis was characterized by widespread expansion of salivary glands by adipocytes with secondary lobular atrophy.4

Patients affected by necrotizing sialometaplasia may present with mild to severe clinical signs. Mild cases are typically characterized by unilateral swelling of the affected salivary gland with occasional pyrexia and anorexia. These cases typically resolve within 10 days regardless of medical intervention. In contrast, severe cases manifest with extreme pain, nausea, dysphagia, anorexia, gagging, and vomiting. These cases are rare and nearly always affect young small terrier breeds. Unfortunately, excision of the affected gland is not curative in these severe cases and euthanasia is often elected due to intractable pain and vomiting. Although both the mild and severe forms have identical histologic features, some authors suggest using the term "salivary gland infarction" to define patients with clinical signs consistent with the mild form of the disease whereas "necrotizing sialometaplasia" should be reserved for small terrier breeds demonstrating severe clinical signs.6

As noted by the contributor, necrotizing sialometaplasia in histologic sections is characterized by extensive, well-demarcated areas of coagulative necrosis bordered by mixed inflammatory cells and fibrosis, vascular thrombosis, and hyperplastic ducts with squamous metaplasia. Necrotizing sialometaplasia can closely resemble salivary gland carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, particularly if only small tissue sections are examined. However, key distinguishing features consistent with necrotizing sialometaplasia include extensive, well-demarcated regions of infarction with normal adjacent salivary gland tissue with a lack of solid acinar proliferation.4

Humans are similarly affected by necrotizing sialometaplasia, though the distribution differs from those described in companion animals. In humans, necrotizing sialometaplasia most commonly affects the minor salivary glands of the hard palate whereas the mandibular salivary gland is most commonly affected in canines and felines. As in veterinary species, the underlying pathogenesis is unclear but the disease is believed to occur due to ischemia of the salivary gland lobules with subsequent infarction. Potential causes of ischemia identified in humans include direct trauma, alcohol and cocaine use, radiation, administration local anesthetics with vasoconstriction agents, surgical procedures, tobacco products, and bulimia. In humans, immunohistochemical stains for cytokeratin 7 (CK7) and α-smooth muscle actin are often used to definitively differentiate necrotizing sialometaplasia from neoplastic disease. Squamous cells associated with necrotizing sialometaplasia are commonly immunopositive for CK7 while most squamous cell carcinomas are not. In cases of necrotizing squamous metaplasia, islands of epithelial cells are typically surrounded by a residual layer of myoepithelial cells immunoreactive to α-smooth muscle actin whereas most squamous cell carcinomas and mucoepidermoid carcinomas are negative.2

References:

1. Brown PJ, Bradshaw JM, Sozmen M, Campbell RH: Feline necrotising sialometaplasia: a report of two cases. J Feline Med Surg 2004:6(4):279-281.

2. Chateaubriand SL, de Amorim Carvalho EJ, Leite AA, da Silva Leonel ACL, Prado JD, da Cruz Perez DE. Necrotizing sialometaplasia: A diagnostic challenge. Oral Oncol. 2021;118:105349.

3. Kim HY, Woo GH, Bae YC, Park YH, Joo YS: Necrotizing sialometaplasia of the parotid gland in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest 2010:22(6):975-977.

4. Lieske DE, Rissi DR. A retrospective study of salivary gland diseases in 179 dogs (2010-2018). J Vet Diagn Invest. 2020;32(4):604-610.

5. Mukaratirwa S, Petterino C, Bradley A: Spontaneous necrotizing sialometaplasia of the submandibular salivary gland in a Beagle dog. J Toxicol Pathol 2015:28(3):177-180.

6. Munday JS, Lohr CV, Kiupel M. Tumors of the alimentary tract. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Press; 2017:548.

7. Saunders GK, Monroe WE: Systemic granulomatous disease and sialometaplasia in a dog with Bartonella infection. Vet Pathol 2006:43(3):391-392.

8. Villano JS, Cooper TK: Mandibular fracture and necrotizing sialometaplasia in a rabbit. Comp Med 2013:63(1):67-70.

9. Ylikontiola L, Siponen M, Salo T, Sandor GK: Sialometaplasia of the soft palate in a 2-year-old girl. J Can Dent Assoc 2007:73(4):333-336.