WSC 2024 Conference 13, Case 1

Signalment:

12-year-old male neutered domestic shorthair cat (Felis catus)

History:

The cat was rescued from a hoarding situation in the year prior to euthanasia. The cat was evaluated for weight loss, hyporexia, icterus, diarrhea, polyuria, polydipsia, hypertension, neurologic signs (circling, head tilt, nystagmus, dullness), eyelid and ear canal masses, retinal detachment, anterior uveitis, and blindness. Lymphoma was suspected and the cat was euthanized.

Gross Pathology:

At necropsy the cat was icteric and the liver, spleen, intestinal walls, and mesenteric lymph nodes were enlarged. The capsular surface of the kidneys was pitted (chronic interstitial nephritis). As noted clinically, there were 4-8 mm raised cutaneous, variably ulcerated or alopecic nodules primarily concentrated around the face, paws and pinnae. There was bilateral axial corneal opacity and roughening (ulceration and edema). In the left eye, the anterior chamber contained flocculent white to yellow material (fibrin) and the iris was diffusely expanded by tan material. In both eyes, the retina and choroid were variably expanded by tan material.

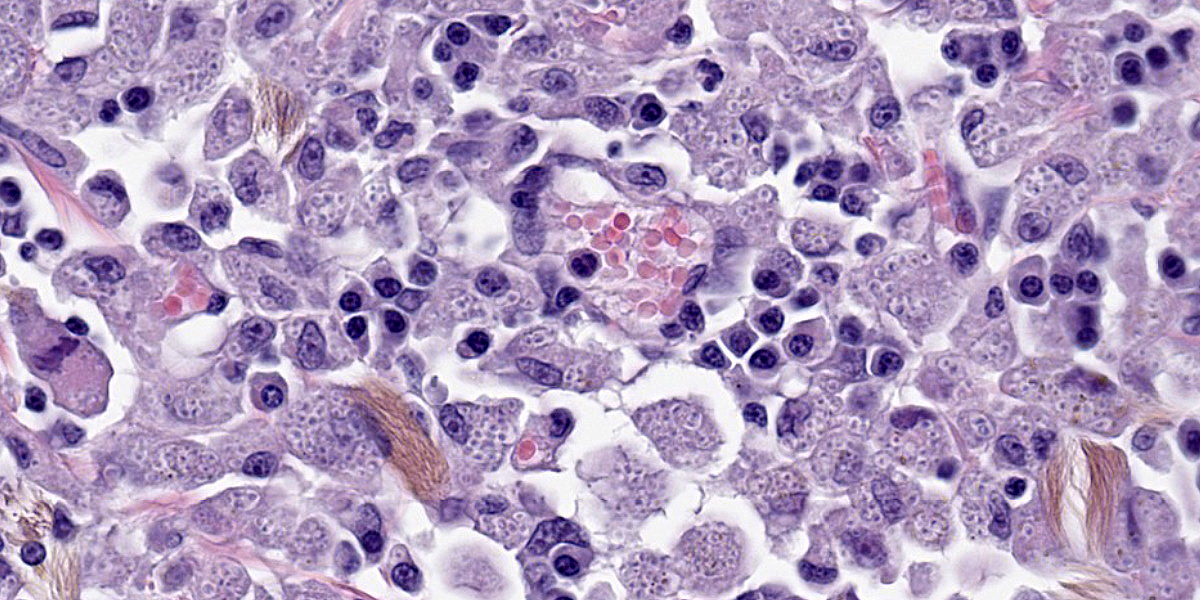

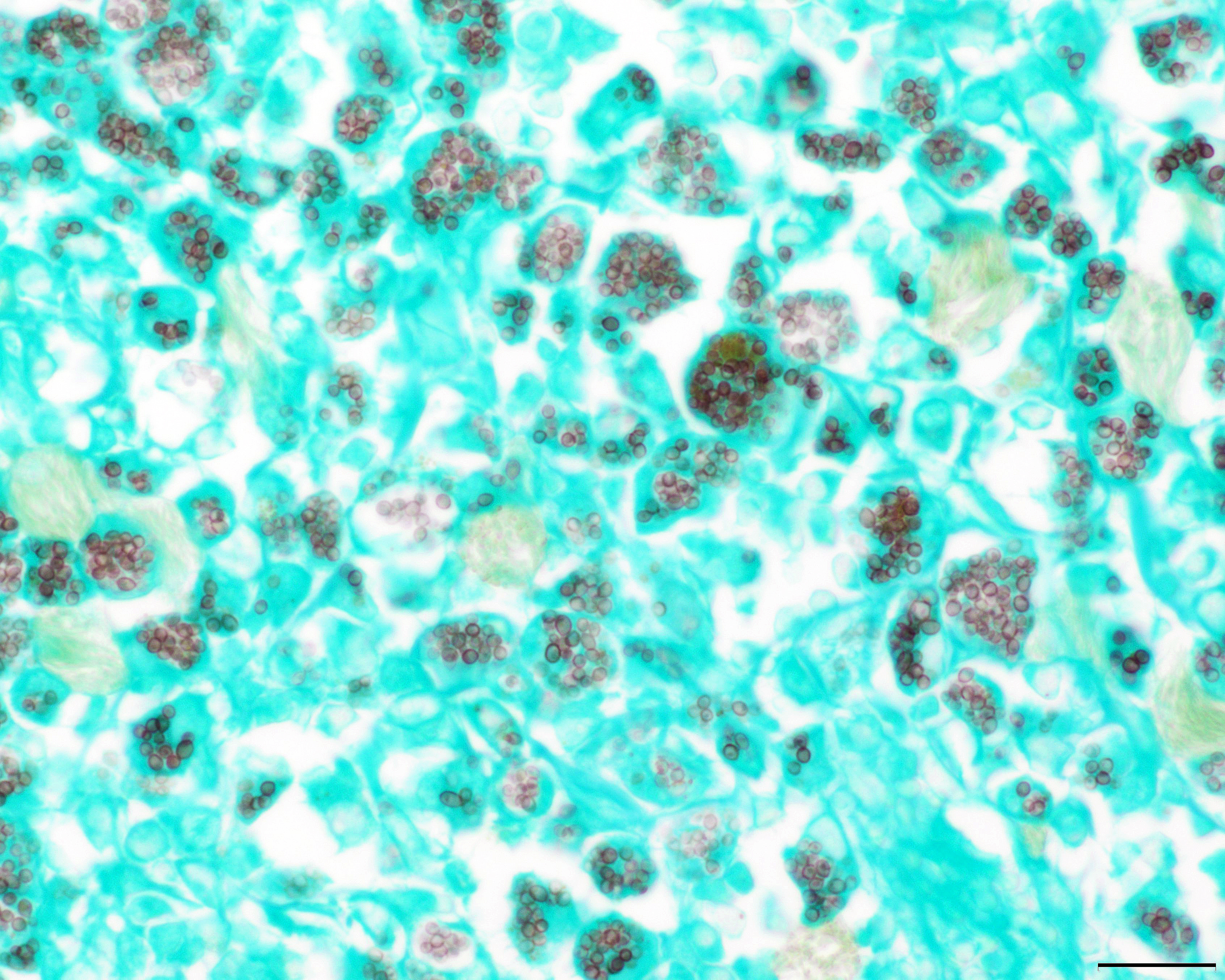

The left eye was more severely affected, but the following lesions are apparent in both eyes. The iris, ciliary body, trabecular meshwork, choroid and retina are variably expanded by sheets of large foamy macrophages that contain myriad, round to oval, 2-4 µm, basophilic yeast surrounded by a clear halo. There are associated lymphocytes and plasma cells. The retina is detached and there is loss of photoreceptor outer segments. There is thinning and mixing of all retinal layers (atrophy). Retinal blood vessels are often cuffed by lymphocytes (retinitis). In some sections, the subretinal space contains abundant fibrin with fewer lymphocytes and yeast-laden macrophages. The lens or lens capsule is present in some sections and exhibits mild peripheral lens fiber swelling and posterior migration of lens epithelial cells (cataract). There is mid-stromal and deep corneal vascularization. In some sections, there is axial corneal ulceration with associated bacterial colonies, fibrin and neutrophils; the adjacent intact corneal epithelium is attenuated.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Eye: Severe diffuse granulomatous endophthalmitis with intrahistiocytic yeasts, retinal detachment, cataract and corneal ulceration.

Contributor’s Comment:

The morphology of the yeasts is most consistent with Histoplasma spp. At necropsy, gross lesions were also identified in the skin, liver, spleen, intestines and lymph nodes, and microscopic examination identified similar lesions and yeast in those tissues as well as in the kidneys and lungs.

In the United States, histoplasmosis is usually due to Histoplasma capsulatum and cases occur most commonly in midwestern and southern states. Bird and bat feces are a common source of infection. Histoplasma spp. are dimorphic fungi and infection is usually acquired by inhalation of microconidia. In the lungs, the microconidia take on the yeast form. The yeast are phagocytized and proliferate by budding intracellularly. The yeast can then spread via the blood and lymphatics to distant sites resulting in systemic infection. Although the lungs are usually the primary site of infection, the skin and gastrointestinal tracts may also be primary sites of infection.

As with many fungal infections, immunocompromised individuals are more susceptible to infection and dissemination. In some immunocompetent hosts, Histoplasma spp. can be dormant until reactivation during times of immunosuppression.1

Clinical signs and lesions depend on the organs affected. As in this case, the lungs, liver, spleen and lymph nodes are commonly affected in systemic histoplasmosis.1

Ocular involvement may be present in about 24% of cats and may include blepharitis, conjunctivitis, chorioretinitis, panuveitis, panophthalmitis, retinal detachment, and optic neuritis.1,2

Contributing Institution:

University of Tennessee

College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences, http://www.vet.utk.edu/departments/path/index.php

JPC Diagnosis:

Eye: Endophthalmitis, granulomatous, diffuse, severe, with retinal detachment and atrophy, and numerous intrahistiocytic yeasts.

JPC Comment:

Histoplasma capsulatum is found primarily in soils enriched in bird and bat guano where it exists as a conidia-forming mold. Once inhaled, the pleasant 37 C temperature of the host converts the organism to a yeast phase composed of 2 to 4µm oval budding yeasts that can be found both extracellularly and within macrophages.3 There are three varieties of Histoplasma capsulatum of veterinary importance: Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum, the most common variant and the subject of this comment; Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii, which primarily causes cutaneous disease in humans and baboons in Africa; and Histoplasma capsulatum var. farciminosum, which causes epizootic lymphangitis, or “pseudoglanders,” in equids.

Exposure to Histoplasma spp. in endemic areas is common, but disease is rare. As the contributor notes, disease, when present, primarily affects the lungs; systemic disease typically results only when the exposed host lacks sufficient cell-mediated immunity to arrest the macrophage-associated spread of yeast throughout the body. Localized, pulmonary, and disseminated histoplasmosis have been described in both domestic and wild felids, and histoplasmosis is reported to be the second most common systemic fungal infection in cats (second only to cryptococcosis).5 The most common body systems affected are the respiratory tract, eyes, musculoskeletal system, hemolymphatic organs, and the skin.5

It is unclear how commonly feline histoplasmosis affects the eyes. In one case series, all cats with confirmed disseminated histoplasmosis had ocular lesions discovered on ophthalmic evaluation, while more recent reports place this number at 24%.2,5 Typical ocular signs include optic neuritis, anterior uveitis, panuveitis, endophthalmitis, choroiditis/chorioretinitis, often with retinal detachment, and secondary glaucoma.5

Research in humans and in animal models has shown that H. capsulatum organisms can persist in tissues in a dormant state for many years.5 In immune-competent animals, the immune system retards or eliminates the organisms’ ability to replicate but does not kill them, leading to the granulomatous lesions that are characteristic of the disease.5 Reactivation of disease may occur with immune suppression, with disseminated disease occurring many years after the host has been removed from exposure to the organism.5 This has implications for ocular histoplasmosis as the eye is an immunologically sequestered tissue that is separated from the rest of the body by the blood-aqueous and blood-retinal barriers.5 While sequestration of H. capsulatum in the eye and subsequent systemic dissemination after discontinuation of antifungal therapy has not been definitively proven, studies of ocular Blastomyces spp. infections suggest that fungal persistence in the eye can delay clearance of the organism and perhaps serve as a reservoir for recrudescent infection.5 The ability to effectively treat ocular histoplasmosis is further complicated by the poor sensitivity of current laboratory tests, such as serial urine and serum antigen assays, at detecting histoplasmosis that is restricted to ocular tissues.5

Detecting the organism was not a particular challenge in this case, however, which delighted conference participants with its somewhat ostentatious display of yeast-laden macrophages. The florid nature of the infection frustrated resident attempts to pinpoint exactly which ocular structures were involved. Our moderator for the week, Dr. Rachel Neto, Assistant Clinical Professor at Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine and ocular pathology enthusiast, allowed that there might be scattered inflammation within the sclera, but felt that this was primarily a uveocentric disease process and preferred to describe the lesion as an endophthalmitis rather than a panophthalmitis.

A considerable amount of discussion centered on the need to read through processing and sectioning artifacts. Dr. Neto particularly noted that she would be cautious in interpreting changes to the drainage angle based on the examined section alone as the section did not include the pupil and was likely a parasagittal cut.Neoplasia should be included on any differential list that is based solely on gross appearance. As this is a cat (evidenced here by the many melanocytes containing filamentous, golden pheomelanin), feline diffuse iris melanoma, lymphoma, and post-traumatic sarcoma should be on the list. Infectious differentials include FIP, Toxoplasma, and the dimorphic fungi. On histologic exam, however, the size, morphology, and intrahistiocytic location of the organism narrows the list considerably to Histoplasma and Leishmania. Dr. Neto also discussed a dimorphic fungus, Blastomyces helicus, that looks virtually identical to Histoplasma capsulatum, is a recently-described cause of feline pneumonitis, and should be considered when confronted with Histoplasma-like organisms in cats.4

References:

- Bromel C, Greene CE. Chapter 58: Histoplasmosis. In: Green CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Ewald MM, Rankin AJ, Meekins JM, McCool ES. Disseminated histoplasmosis with ocular adnexal involvement in seven cats. Vet Ophthalmol. 2020;23: 905-912.

- Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(1):115-132.

- Martinez CR, Jensen TD, Bradley AM, Bohn AA. Pathology in Practice. JAVMA. 202;256(8):1895-1897.

- Smith KM, Strom AR, Gilmour MA, et al. Utility of antigen testing for the diagnosis of ocular histoplasmosis in four cats: a case series and literature review. J Feline Med Surg. 2017;19(10)1110-1118.