Signalment:

Gross Description:

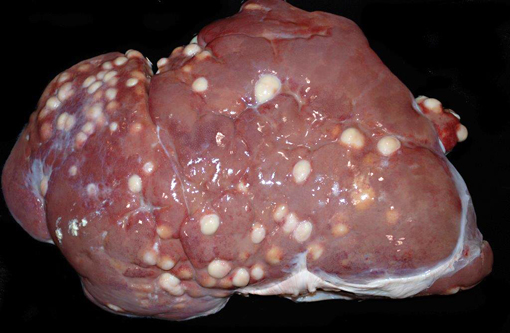

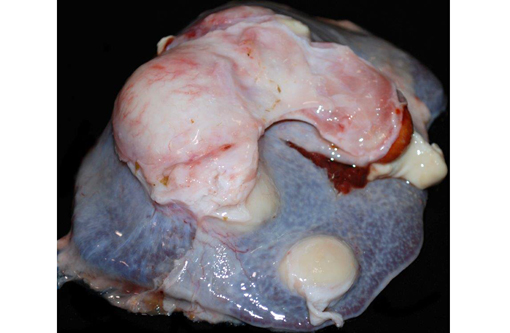

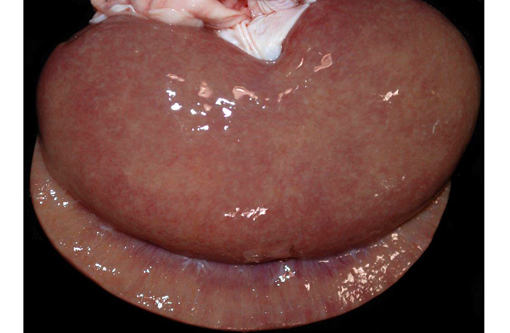

The mediastinal lymph nodes are expanded by abundant amounts of caseous material. Scattered throughout the liver and spleen are dozens of variably-sized abscesses. The kidneys are slightly tan to grey, and the subcapsular surface is slightly granular and mottled with pinpoint, tan foci.

Histopathologic Description:

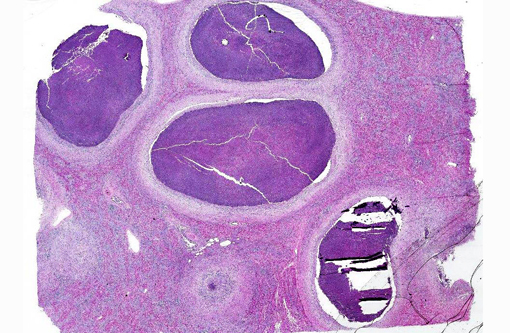

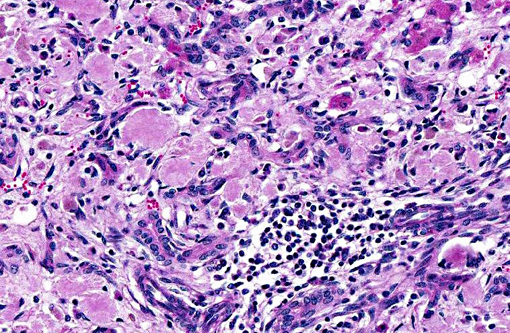

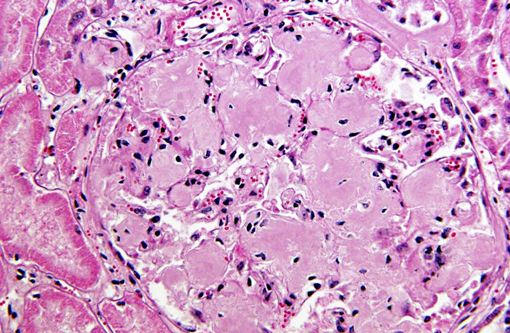

Within the spleen are numerous large abscesses, and surrounding periarteriolar lymphoid aggregates are large aggregates of amyloid. Amyloid distends glomerular tufts. Histochemical staining with Congo red confirms the presence of amyloid as congophilic material that is birefringent and apple green on polarization.

Histologic examination of the lungs revealed an acute, neutrophilic interstitial pneumonia.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis is a gram-positive, pleomorphic, facultative, anaerobic bacillus that commonly causes disease in several domestic species, including goats, sheep, cattle, and horses. In small ruminants, C. pesudotuberculosis is a common cause of lymphadenitis (caseous lymphadenitis), and it may cause pectoral muscle abscesses in horses (pigeon fever) and ulcerative lymphangitis in cattle. In addition, C. pseudotuberculosis may cause subcutaneous abscesses, splenic abscesses, embolic nephritis, and orchitis.(6) As in this case, C. pseudotuberculosis infection is occasionally associated with systemic amyloidosis in small ruminants.(4,7)

Systemic amyloidosis refers to the deposition of amyloid in multiple organs, as opposed to localized amyloidosis, where amyloid is deposited in a single organ. Systemic amyloidosis may result from an immunocyte dyscrasia (primary systemic amyloidosis) or from chronic inflammation (secondary systemic amyloidosis). Amyloid deposited in secondary systemic amyloidosis is composed of AA (amyloid-associated) protein that forms β-pleated sheets. AA protein is derived from serum amyloid-associated (SAA) protein which is produced by the liver as an acute phase reaction to inflammation.(6)

In small ruminants, secondary systemic amyloidosis has been reported to most commonly result from pneumonia,(5,7) though it may also occur in association with nephritis,(5) polyarthritis, urolithaisis, and mastitis.(7) Typically, small ruminants with secondary systemic amyloidosis may have deposits of amyloid in the kidneys, spleen, liver, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, adrenal gland, and vascular tunica media.(2,7)

As in this case, renal glomeruli may be more effected than the renal medulla, and amyloid may form aggregates surrounding splenic periarteriolar lymphoid aggregates.(7) In contrast to this case, hepatic amyloidosis in small ruminants, is more commonly associated with expansion of the sinusoids rather than the portal triads.(4,7)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Based on the microscopic findings in this case, Fusobacterium necrophorum was suggested as a possible etiologic agent. Hepatic necrobacillosis in ruminants typically occurs when this opportunistic, gram-negative bacterium enters portal circulation as a sequela to toxic rumenitis.(6) Gram-negative septicemia, due to agents such as E. coli or Salmonella spp., could also result in hepatic abscessation. In this case, a Massons trichrome and a Gram stain reveal thick connective tissue capsules surrounding multiple abscesses containing numerous gram-positive bacilli. This, in combination with the culture results as reported by the contributor, identifies C. pseudotuberculosis as the underlying cause.

The contributor provides an excellent summary of both Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis (which is a potential zoonosis) and systemic amyloidosis in ruminants. Although C. pseudotuberculosis is relatively poorly characterized, some virulence determinants include the following: the leukotoxic phospholipase D exoprotein (PLD) contributes to the destruction of caprine macrophages during infection; the fagABC operon and the fagD gene play a role in virulence and are involved in iron acquisition; the high cell wall concentration of lipids aids in resistance to enzymatic digestion, allowing the bacterium to persist as a facultative intracellular parasite; and CP40, an immunogenic protein that exhibits proteolytic activity as a serine protease.(9) Additionally, recent studies have demonstrated that serum concentrations of haptoglobin (Hp), serum amyloid A and α1 acid glycoprotein are increased in experimental models of ovine caseous lymphadenitis due to C. pseudotuberculosis, which may predispose affected animals to systemic amyloidosis.(1) Readers are urged to review WSC 2013-2014, conference 6, case 4 for a more detailed discussion of amyloidosis.

References:

1. Bastos BL, Loureiro D, Raynal JT, et al. Association between haptoglobin and IgM levels and the clinical progression of caseous lymphadenitis in sheep. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9(1):254-262.Â

2. Biescas E, Jiron W, Climent S, Fernandez A, Perez M, Weiss DT, et al. AA amyloidosis induced in sheep principally affects the gastrointestinal tract. J Comp Pathol. 2009;140:238-246.

3. Crawford JM, Burt AD. Anatomy, pathophysiology and basic mechanisms of disease. Burt AD, Portmann BC, Ferrell LD, eds. MacSweens Pathology of the Liver. 6th ed. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone Elesvier; 2012:45-48.

4. Farnsworth GA, Miller S. An unusual morphologic form of hepatic amyloidosis in a goat. Vet Pathol. 1985;22:184-186.

5. Kingston RS, Shih MS, Snyder SP. Secondary amyloidosis in Dall's sheep. J Wildl Dis. 1982;18:381-383.

6. McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:36-38, 182-189, 284-288, 429-432, 627-628, 758-764, 1031-1032, 1141-1142.Â

7. Mensua C, Carrasco L, Bautista MJ, Biescas E, Fernandez A, Murphy CL, et al. Pathology of AA amyloidosis in domestic sheep and goats. Vet Pathol. 2003;40:71-80.

8. Nakanuma Y, Zen Y, Portmann BC. Diseases of the bile ducts. Burt AD, Portmann BC, Ferrell LD, eds. MacSweens Pathology of the Liver. 6th ed. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone Elesvier; 2012:495-497.

9. Pinto AC, de S+�-� PH, Ramos RT, et al. Differential transcriptional profile of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis in response to abiotic stresses. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1-14.