Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 4

18 September 2019

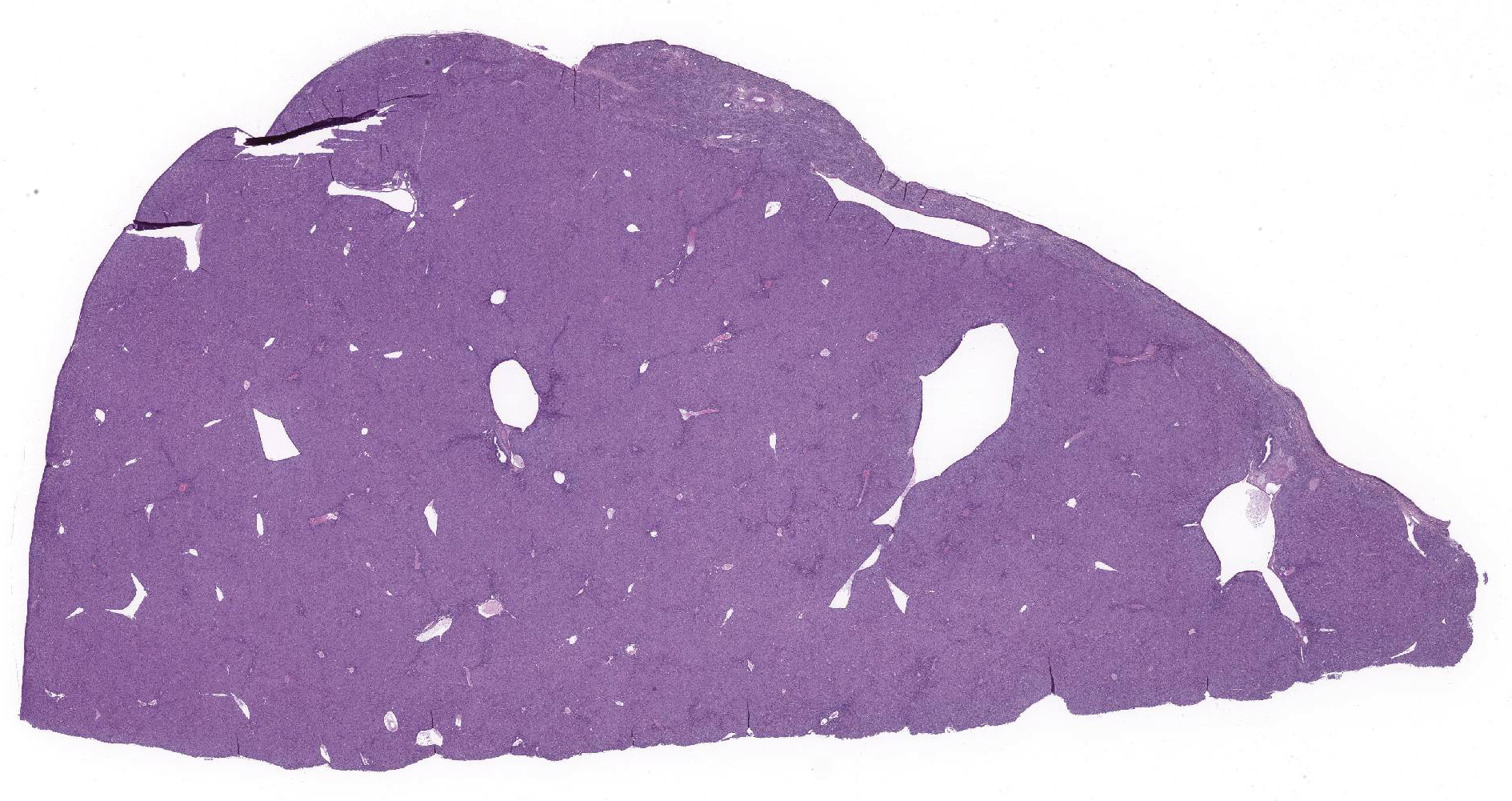

CASE II: 17-0894 (JPC 4111545).

Signalment: Merino, Female, 12 months old

History: 14 of 130 twelve month old lambs died during a two week period in late Autumn. Sheep were grazing pastures containing witchgrass (Panicum capillare)

Gross Pathology: Cutaneous photosensitization of eyelids, muzzle and coronet bands. Severe generalized jaundice, very swollen yellow and firm liver with enhanced lobular pattern. Dark yellow-brown staining of kidneys.

Laboratory results: None performed.

Microscopic Description:

Microscopic Description:

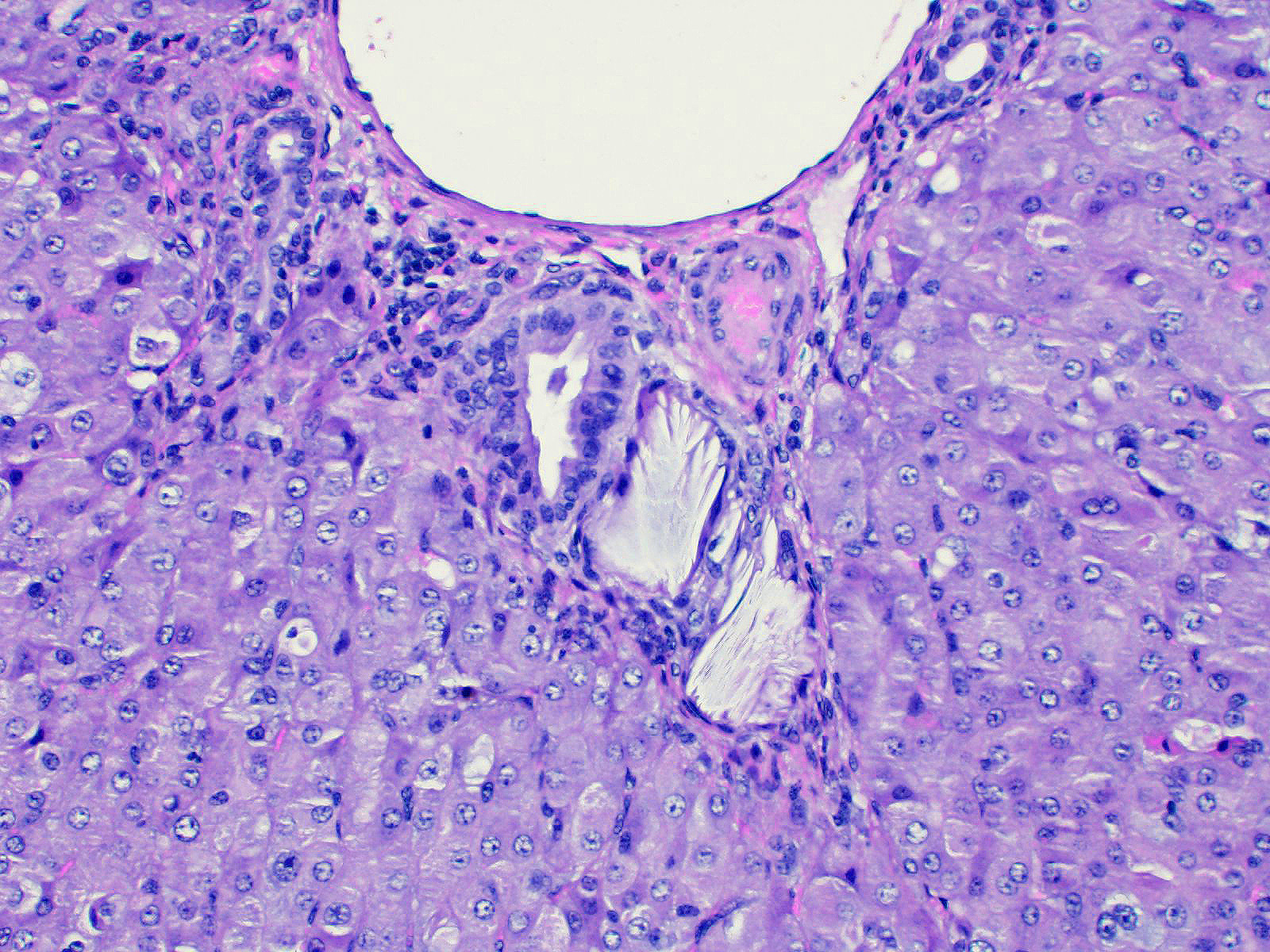

Liver: Lobar borders of liver are rounded. There is mild to moderate infiltration of periportal interstitium by lymphocytes, macrophages, and variable neutrophils, mild to moderate expansion of periportal fibrocollagenous connective tissue, and mild to moderate bile duct hyperplasia. Within periportal interstitium there are clear acicular clefts (crystal ghosts) surrounded by fibroblasts and collagen. Rare crystal ghosts are present in the bile ducts associated with tubular epithelial degeneration and attenuation, and less often present in the sinusoids. Diffusely, there is moderate hepatocellular swelling characterized by feathery to vacuolar cytoplasm and scattered individual cell necrosis, most notably in periportal regions. Kupffer cells are often enlarged with vacuolar to lightly pigmented cytoplasm, or clear cytoplasm. Bile canaliculi are sometimes distended by light brown-orange pigment (bile plugs).

Microscopic findings in other tissues included myocardial sarcocystosis, moderate to severe neutrophilic bronchointerstitial pneumonia, and renal tubular epithelial degeneration and cytoplasmic pigmentation (bilirubin, other) with pigmented tubular casts.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: chronic-active mixed cholangiohepatitis with cholestasis, periportal fibrosis and crystal ghosts (crystal cholangiohepatopathy).

Contributor Comment: Crystal-associated hepatopathy and secondary photosensitization in these lambs developed following exposure to witchgrass (Panicum capillare) in pasture. No crystals were observed under direct nor polarized light, however acicular clefts (crystal ghosts) were identified in the periportal interstitium, bile ducts and rarely in the sinusoids. The duration that lambs had been grazing this pasture prior to the onset of clinical signs was not recorded in the submission. Onset of hepatotoxicity in sheep experimentally exposed to another Panicum species, kleingrass (Panicumn coloraturum), was variable, occurring as early as three days to several weeks post initial exposure 1. Following natural exposure of sheep to P. schinzii, the clinical appearance of hepatotoxicity was reported to have occurred within five days of the flock being moved onto affected pastures 2.

Crystal hepatopathy has been reported in ruminants and horses following exposure to Panicum grasses 1, as well as Brachiaria 3,4, and Narthecium14 grass species. These plants contain steroidal saponins and affected ruminants often develop bile crystals composed of the calcium salts of steroidal saponin glucuronides.6,8-10

Hepatic lesions described in natural and experimental Panicum grass toxicity in sheep and horses include patchy or scattered hepatocellular necrosis, vacuolation and swelling, nuclear chromatin clumping, presence of birefringent crystals in small bile ducts, bile canaliculi or within sinusoidal phagocytes, fibrosis, bile duct proliferation, and lymphocytic hepatitis.1,7 Crystals may not always be observed; no crystals were identified in affected livers of horses and sheep following exposure to Panicum dichotomiflorum, 7 and this was thought to be to the short exposure time to the grasses (feeding trials only lasted 12 days). In experimental work done elsewhere, sheep grazing kleingrass for less than 10 days did not have observable crystals in the liver 1. In kleingrass toxicity, crystals are reportedly soluble in acidified ethyl alcohol, acetic acid, pyridine, chloral hydrate, and methanol, but not in xylene, petroleum ether, diethyl ether, acetone, water, or cold ethyl alcohol. 1

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

School of Animal and Veterinary Sciences

The University of Adelaide,

Roseworthy, South Australia, 5371, Australia

JPC Diagnosis: Liver:

Cholangiohepatitis, necrotizing and histiocytic , multifocal, mild, with mild

bridging portal fibrosis, biliary hyperplasia, subcapsular hepatocellular loss

intrahistiocytic and intraductal crystal formation.

JPC

Comment: The genus Panicum is a large group of grasses containing

up to 600 different species of grasses in tropical and temperate regions around

the world.13 The majority may be used as forage for livestock;

however a limited number of species such as those mentioned above, may result

in crystal associated hepatopathy, with the formation of crystals within bile

ducts and resultant hepatic damage as the most important lesion. The

biotransformed saponins within these plants are conjugated with gluruconic acid

and excreted in the bile, where they may complex with calcium to form an

insoluble salt. Photosensitization in affected animals is usually the result

of biliary damage and inability to conjugate phytoporphyrins (phylloerythrin),

a chlorophyll derivative produced by bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract.

Phylloerythrin is a photoactive compound which is excited by ultraviolet light

in lightly pigmented and poorly haired areas of the body.

A recent article by Sillman et al12 details toxicity in 3-month Boer

goats clearing a weedy livestock lot. After a month of the lot, affected

animals developed icterus and inappetence with marked hyperbilirubinemia,

elevated aspartate aminotransferase and variable levels of alanine

aminotransferase. Examination of the lot showed a tremendous growth of Panicum

dichotomiflorum. At autopsy, portal areas were mildly fibrotic and

contained clusters of macrophages centered on large, acicular crystals. Mild

hepatocellular vacuolation and biliary hyperplasia were also noted. Previous

reports of P. dichotomiflorum described intoxication in a variety of

species, including nursing and juvenile lambs and horses, although many reports

note that other animals of various species, breeds, or ages grazing the same

forage were unaffected. The report by Sillman et al. also notes the presence of

tubular nephrosis in the goat, which had not been previously described.

Evidence of photosensitization was not noted in these cases. 12

Another recent report describes the first instance of hepatogenous photosensitization due to steroidal saponin toxicity in macropods. Steventon et al.13 describes an outbreak of blindness or photophobia in 95 grey kangaroos in New South Wales, Australia. Affected animals developed icterus, photophobia (abnormal shade seeking behavior), and blindness resulting with severe corneal edema and inflammation and necrotizing dermatitis of the eyelids, pinnae, and forearms. Examination of the liver of affected animals revealed crystal formation in small bile ducts with mild granulomatous inflammation and portal fibrosis. The presence of crystal-associated damage and inflammation with bile ducts prompted examination of the site of the outbreak, which was dominated by a heavy growth of Panicum gilvum ("sweetgrass(" or ("sweet panic(".)13

Sporidesmin, a plant saponin from spores of Pithomyces chartarum which causes a well-known syndrome of photosensitization (("facial eczema(") and severe hepatic damage in New Zealand. The excretion of unconjugated sporidesmin in the bile results in oxidative injury to the biliary epithelium, leakage of biliary components into the surrounding tissue, and occasionally necrosis of vessels in adjacent parenchyma.4 When complemented with concurrent ingestion of saponins of Tribulus terrestris a condition known as ("geeldikkop(" is created, in which crystal formation within bile ducts and within the whitish contents of the gallbladder is noted.4

Conference

participants were impressed by the significant icterus demonstrated in the

gross lesions in this case as compared with the relative lack of significant

fibrosis and hepatocellular damage. While information about possible exposure

to copper was not mentioned, a JPC-run rhodamine stain was considered

unremarkable in this case.

Additional discussion centered on a second lesion at the edge of the capsule, in which there is a sharply demarcated area of hepatocellular loss, with retention and mild proliferation of bile ductules, and marked fibrosis. Dr. John Cullen of NC State University was consulted on the potential etiology of this lesion. He believes that it represents an area of ischemia which may be seen at the edge of the liver of ruminants. While never proven, it may be seen adjacent to the rumen in ruminants and cecum in horses, suggesting that distention of these organs may compromise venous return in these focal area, resulting in hepatocellular death. The preservation and even mild duplication of bile ductules is potentially the result of their nourishment by branches of the hepatic artery which may not be as susceptible to potential compression-induced ischemia. This lesion does not resemble a ductal plate abnormality, or an extension of the toxic process seen in the rest of the section.

References:

1 Bridges CH, Camp BJ, Livingston CW, Bailey EM: Kleingrass (Panicum coloratum L.) poisoning in sheep. Vet Pathol 1987:24(6):525-531.

2 Button C, Paynter DI, Shiel MJ, Colson AR, Paterson PJ, Lyford RL: Crystal-Associated Cholangiohepatopathy and Photosensitization in Lambs. Australian Veterinary Journal 1987:64(6):176-180.

3 Cruz C, Driemeier D, Pires VS, Schenkel EP: Experimentally induced cholangiohepatopathy by dosing sheep with fractionated extracts from Brachiaria decumbens. J Vet Diagn Invest 2001:13(2):170-172.

4. Cullen JM, Stalker MA. Liver and Biliary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb Kennedy and Palmers' Pathology of Domestic Animals, 6th Edition. St. Louis MO, Elsevier. Vol 2, , 338-340.

4 Graydon RJ, Hamid H, Zahari P, Gardiner C: Photosensitization and Crystal-Associated Cholangiohepatopathy in Sheep Grazing Brachiaria-Decumbens. Australian Veterinary Journal 1991:68(7):234-236.

5 Holland PT, Miles CO, Mortimer PH, Wilkins AL, Hawkes AD, Smith BL: Isolation of the Steroidal Sapogenin Epismilagenin from the Bile of Sheep Affected by Panicum-Dichotomiflorum Toxicosis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1991:39(11):1963-1965.

6 Johnson AL, Divers TJ, Freckleton ML, McKenzie HC, Mitchell E, Cullen JM, et al.: Fall panicum (Panicum dichotomiflorum) hepatotoxicosis in horses and sheep. J Vet Intern Med 2006:20(6):1414-1421.

7 Lancaster MJ, Vit I, Lyford RL: Analysis of Bile Crystals from Sheep Grazing Panicum-Schinzii (Sweet Grass). Australian Veterinary Journal 1991:68(8):281-281.

8 Miles CO, Munday SC, Holland PT, Lancaster MJ, Wilkins AL: Further Analysis of Bile Crystals from Sheep Grazing Panicum-Schinzii (Sweet Grass). Australian Veterinary Journal 1992:69(2):34-34.

9 Munday SC, Wilkins AL, Miles CO, Holland PT: Isolation and Structure Elucidation of Dichotomin, a Furostanol Saponin Implicated in Hepatogenous Photosensitization of Sheep Grazing Panicum-Dichotomiflorum. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1993:41(2):267-271.

10 Regnault TR: Secondary photosensitisation of sheep grazing bambatsi grass (Panicum coloratum var makarikariense). Aust Vet J 1990:67(11):419.

11. Sillman SJ, Lee ST, Clabrn J, Borush H, Harris SP. Fall panicum (Panicum dichotomiflorum) toxicosis in three juvenile goats. J Vet Diagn Investig 31(1):90-93.

12. Steventon CA, RAidal SR, Quinn JC, Peters A. Steroidal saponin toxicity in Eastern grey kangaroos;: A novel clinicotahologic presentation of hepatogenous photosensitizationJ Wild Dis 2019; 54(3):491-502.

13 Uhlig S, Wisloff H, Petersen D: Identification of cytotoxic constituents of Narthecium ossifragum using bioassay-guided fractionation. J Agric Food Chem 2007:55(15):6018-6026.