Signalment:

Gross Description:

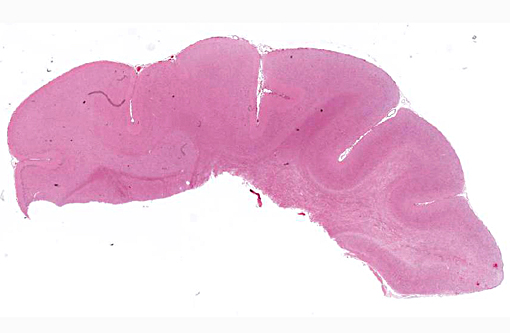

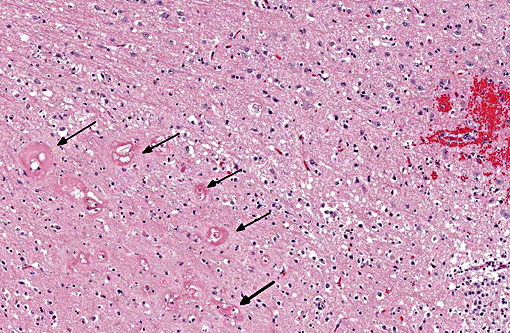

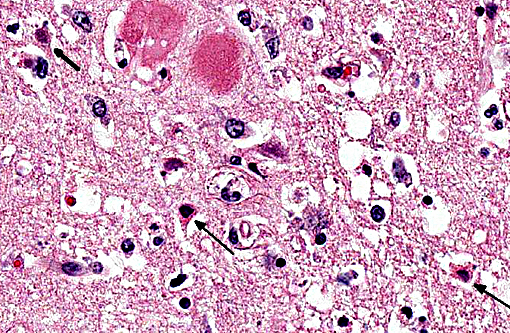

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

- Stress-induced (white coat) hypertension: transitory artifactual increase (median rise of 17.6 + 5.9 mmHg) secondary to activation of the sympathetic nervous system in the classical fight or flight response;

- Secondary hypertension: most common and associated with systemic diseases or treatments including chronic renal disease, hyperthyroidism, primary hyperaldosteronism, pheochromocytoma, diabetes mellitus and erythropoietin treatment; and

- Idiopathic (primary or essential) hypertension: about 20% of hypertension in cats occurs in the absence of other demonstrable disease conditions.

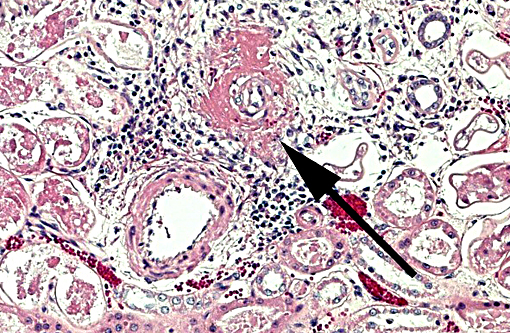

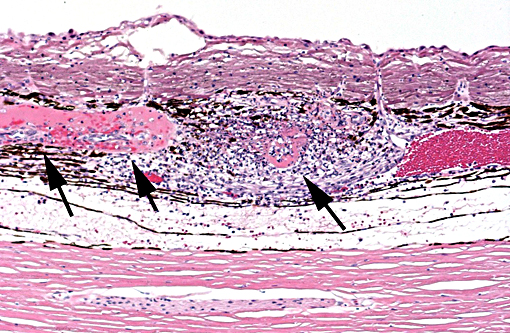

Target organ damage (TOD) is a risk in the face of uncontrolled hypertension with the heart, brain, eyes and kidneys being at greatest risk. The cat of this report showed TOD in the brain as described above. Changes in the eyes and kidneys were also focused largely on vascular structures, specifically arterioles, with similar effacement by amorphous eosinophilic material with small amounts of nuclear debris, commonly known as fibrinoid change or necrosis. This cat presented with acute onset of blindness and an anxious demeanor with rapid deterioration to seizuring and stupor. This is a classical presentation for target organ damage in a hypertensive cat with the first noted sign often being acute blindness associated with catastrophic effusive retinal detachment (Fig. 2). Sudden onset of intracranial neurological signs is also common. Renal and cardiac changes are generally more insidious. Accelerated progression of chronic kidney disease and development of congestive heart failure associated with left ventricular hypertrophy, respectively, are reported.(3) Pathogenesis of the insidious conditions is poorly understood, particularly regarding cause and effect.

The risk of target organ damage rises as the blood pressure rises.(4,5) Risk is minimal at <150mmHg, mild at 150-159mmHg, moderate at 160-179mmHg and severe at >180mmHg. This cat had a recorded pressure of 230mmHg at presentation. The vascular lesions in the brain, eyes and kidneys are acute suggesting a relatively short course of hypertension in this cat. There is no evidence to suggest hyperplastic vascular changes that would be seen as a response to sustained hypertension. It has been suggested that vascular remodeling can occur within 14 days of onset of hypertension.(1)

Hypertension in this cat was considered idiopathic despite being younger than reported age of >12 years for development of idiopathic hypertension.(5) Complete histological evaluation did not show pathology consistent with any of the conditions associated with secondary hypertension. Secondary hypertension is most commonly seen in cats with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or with hyperthyroidism. Many cats with systemic hypertension show some degree of CKD. It is often unclear whether the hypertension initiates renal damage or systemic hypertension develops as a consequence of reduced renal function.

Hyperthyroidism has been considered a risk factor for systemic hypertension with recent information suggesting this risk may be overstated.(3)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The moderator discussed duration of injury as determined by relative populations of glial cells. It generally takes approximately 4-5 days to see a prominent astrocyte response; in this case there is a mild increase in the number of astrocytes, and a much more prominent increase in the number of microglial cells. Microglial cells respond more rapidly to CNS injury, generally increasing in number within 24 hours, and consequently there was speculation this lesion was approximately 2-3 days duration, which corresponds to the contributors comment above regarding the acute nature of changes in the brain.

Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow normally prevents excesses of pressure and flow within the brain that can result in excess pressure related damage; however, there are upper limits on this autoregulatory mechanism. When this mechanism fails in cases of prolonged and/or excessive systemic blood pressure, vessels become distended and endothelial tight junctions open, resulting in extravascular leakage of fluid, and edema is the end result. Depending on the severity, cerebral edema may be visible grossly along with widening and flattening of the cerebral gyri, and caudal herniation of the cerebellum through the foramen magnum due to increased intracranial pressure. Histologically, as seen in this case, vacuolation of the neuropil is present, and may be predominantly in the white matter. Vascular lesions can include arteriolar hyalinosis, which may reflect endothelial damage, and leakage of fibrin and other plasma components into the vessel wall and extravascular space; this change may occur prior to onset of fibrinoid vascular necrosis. Hyperplastic arteriosclerosis, microhemorrhages and perivascular cuffing by inflammatory cells may also be seen depending on degree and duration of hypertension.(1,4)

References:

1. Brown CA, Munday JS, Mathur S and Brown SA. Hypertensive encephalopathy in cats with reduced renal function. Vet Pathol. 2005;42:642-649.

2. Brown S, Atkins C, Bagley R, et al. ACVIM consensus statement: Guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and management of systemic hypertension in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:542-558.

3. Jepson R. Feline hypertension: Classification and pathogenesis. J Feline Med Surg. 2011;13:25-34.

4. Kent M. The cat with neurological manifestations of systemic disease: Key conditions impacting on the CNS. J Feline Med Surg. 2009;11:395-407.

5. Stepien RL. Feline hypertension: Diagnosis and management. J Feline Med Surg. 2011;13:35-43.