Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 4, Case 3

Signalment:

Adult, female, Pantaneira, Ovis aries, sheep.History:

On July 24, 2018, the ewe presented with a mild nasal mucohemorrhagic discharge. When rechecked on July 28, 2018 the discharge had become more severe and the ewe was dyspneic and gasping. There was cranium facial asymmetry of the right eye due to exophthalmos. The protrusion of the eyeball resulted in keratitis and corneal ulceration. The ewe was treated with homeopathy with no success. Due to poor prognosis, the ewe was euthanized 34 days after the onset of clinical signs. During July-August, 2018, two more cases of the same disease occurred on the premises.Gross Pathology:

The cadaver denoted poor nutritional status. In the right orbital region, there was a severe increase in periocular volume caused by exophthalmos and resulting in marked cranial asymmetry.The eyeball was not visible since it was covered by reddish, swollen, ulcerated mucosa. At the cut surface, it was evident that the eyeball had been replaced by a white irregularly outlined mass that was sparsely sprinkled with red spots, with a greyish granular center (caseous material). In the subcutaneous region of the right nasal bone, there was a mass of 2x0.5 cm, the cut surface of which looked similar to that of the ocular mass, but without caseous spots. There was moderate to marked edema throughout the right periocular region.

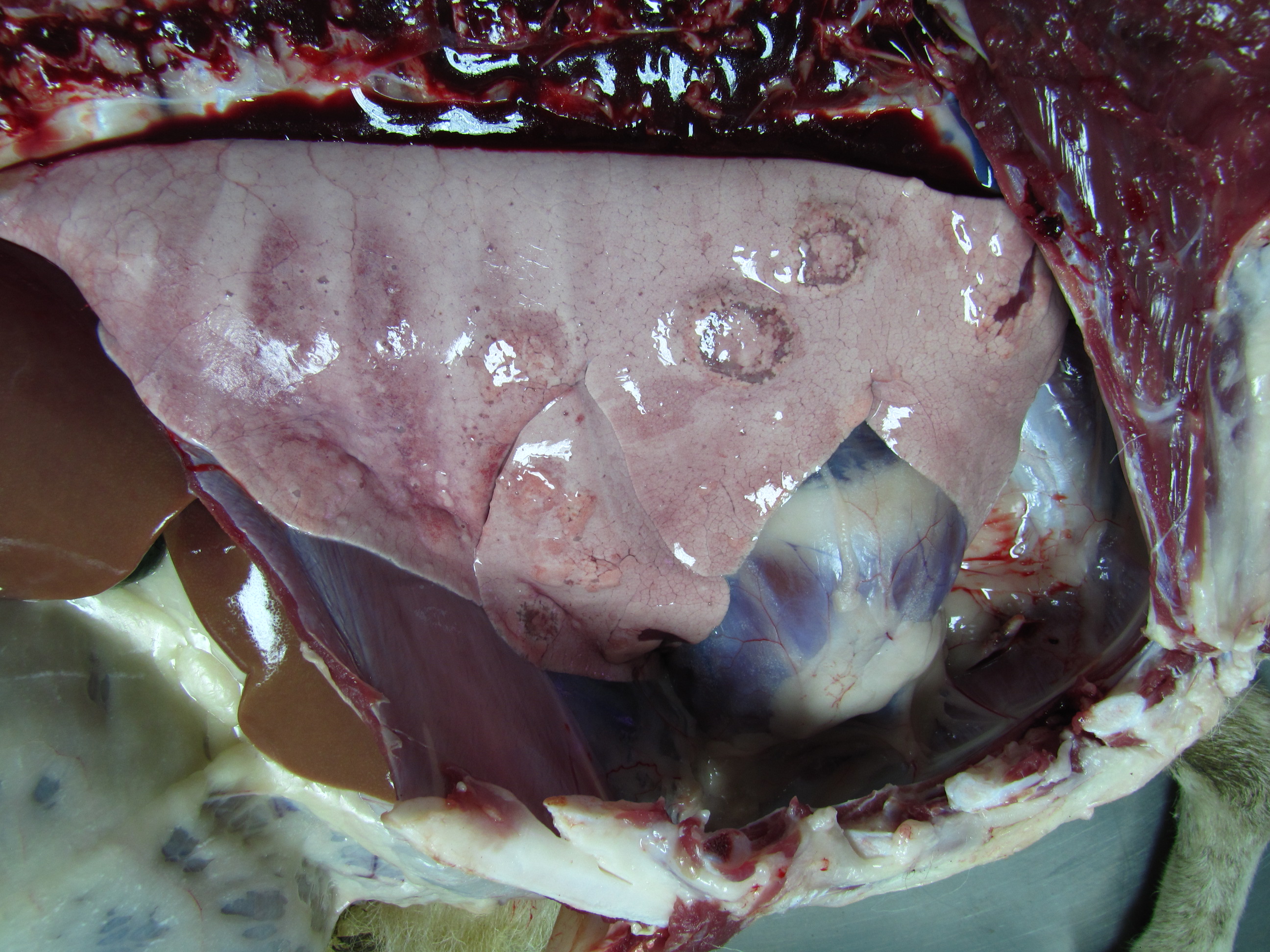

In the lung, there were several soft, yellowish subpleural nodules of variable sizes (0.5-2cm) and surrounded by a red rim.

The omentum had fair adipose tissue depots, but the serosa of intestines was pale. There were moderate numbers of small hard grey nodules in the serosal aspects of some intestinal loops (calcified nodules of Oesophagostomum sp. larvae). The liver was moderately pale, with evidence of the lobular pattern; in the left lobe, there was a firm-to-hard grey nodule interpreted as a calcified hydatid. In both kidneys, irregular pale areas were observed in the natural surface which extended to the cortical region, and in some points reaching the limit of the corticomedullary junction.

On mid-sagittal section of the head, the right side was completely destructed with loss of nasal conchae which are replaced by a large firm-to-soft, focally friable mass with irregular contours. The mass extended to the pharyngeal region and invaded the cranial cavity, destroying the turbinates and striking the frontal lobe of the brain. After the removal of the cartilage, it was observed that the conchae on the left side were intact but had moderate congestion. After removal of the right hemisphere, an increase in the volume of the olfactory bulb was observed, which was swollen, dark and with a caseous lesion at its junction with the frontal lobe. In the frontal portion of the right cerebral hemisphere, the meninges were thickened, and there was a focal loss of gray matter.

Laboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

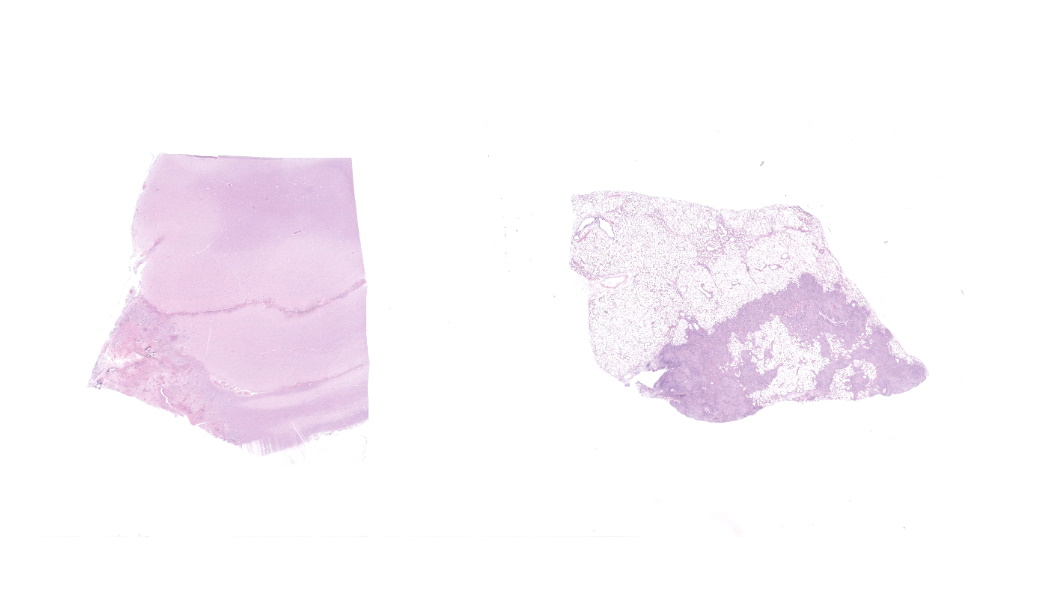

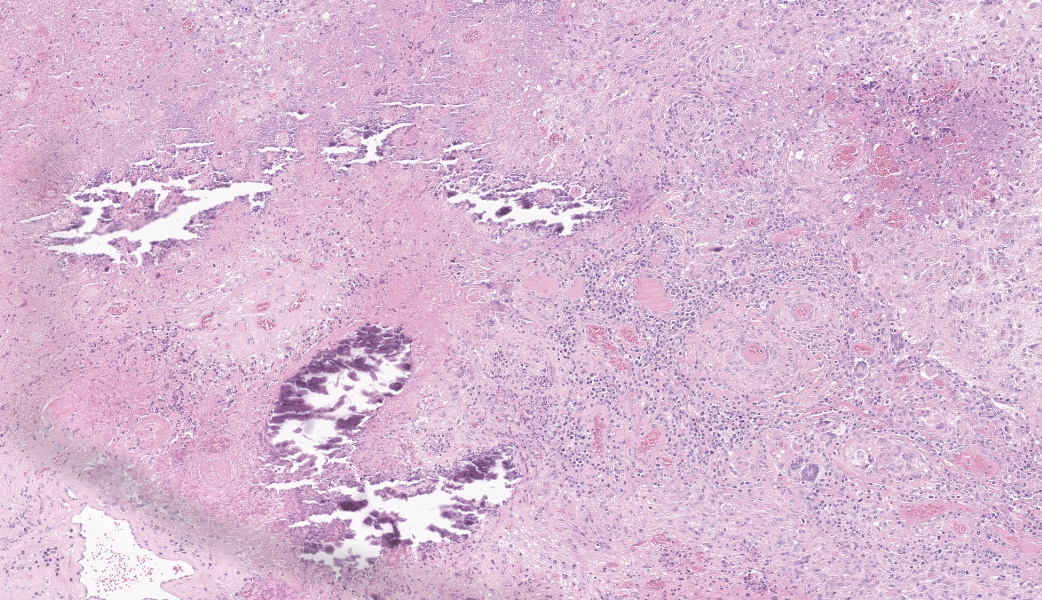

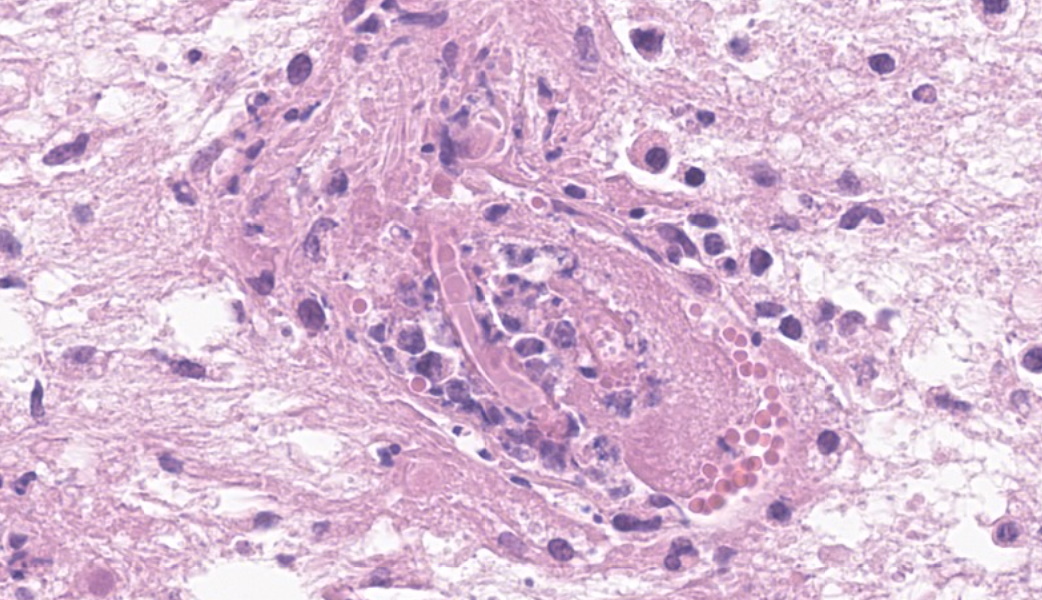

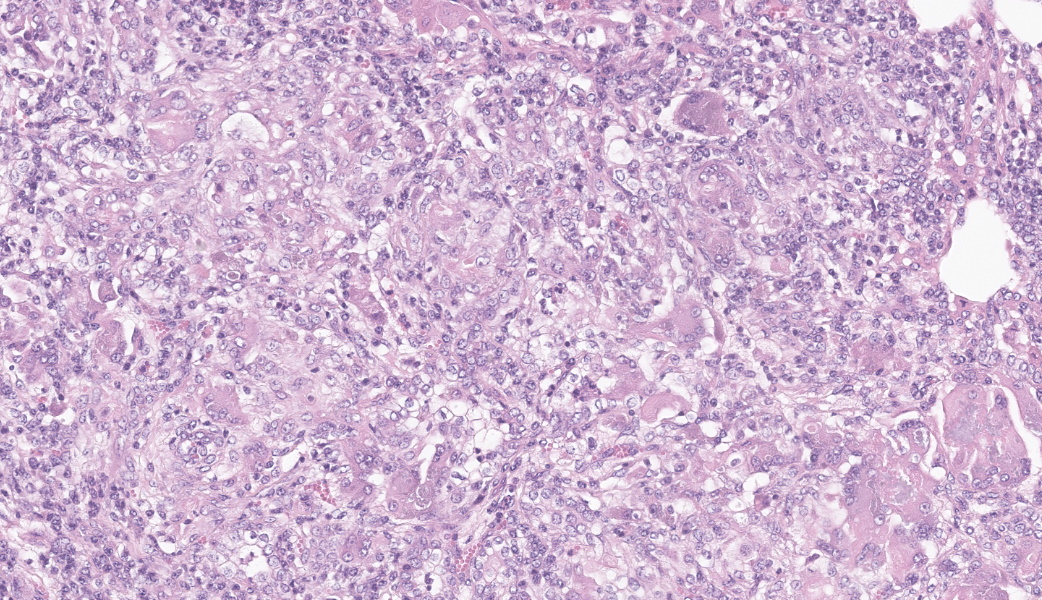

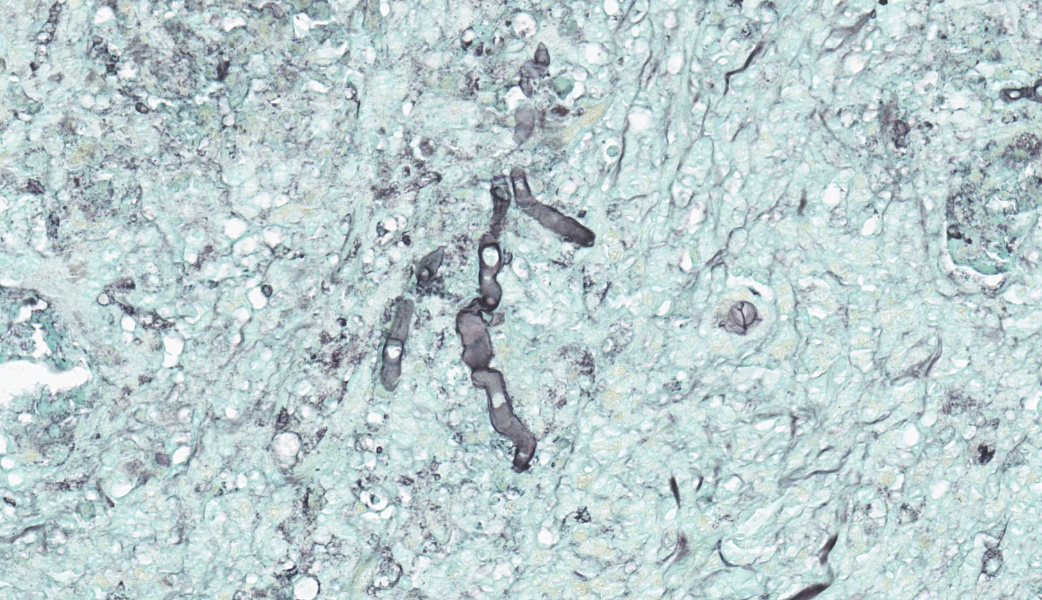

Brain, right frontal lobe: the leptomeninges are focally extensive and moderately expanded by pyogranulomatous exudate. The exudate is formed by nodular to coalescent (mild slide variation) collections of epithelioid macrophages, lesser eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells and few Langhans giant cells. The granulomatous component is admixed with plump fibroblasts, thin bundles of fibrous tissue, and multifocal aggregates of granular, deep basophilic and dense material (mineral). Among the cell debris or in the cytoplasm of the multinucleated cells there are tubularly elongated (when longitudinally sectioned), circular or oval (when transversally sectioned) structures barely stained and hard to visualize in hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stained slide ("negative" images of fungal hyphae). The hyphae are characterized by a body that is hollow or filled with eosinophilic or basophilic granular material and surrounded by varying, but mostly scarce, amounts of strongly eosinophilic, smooth or granular material (Splendore-Hoeppli reaction). The wall of medium-sized arteries in the affected areas is segmentally or cincunferentially expanded by acellular, bright eosinophilic and homogeneous material (fibrinoid necrosis) and occasionally there are hyphae infiltrating the vessel wall or associated with thrombosis in the vessel lumen. There is a focally extensive area of necrosis of liquefaction, swelling of astrocytes and cavitation of nervous tissue, where the parenchyma has been replaced by proliferating microglial cells, many of which already differentiate into foamy macrophages (gitter cells). Perivascular cuffs containing up to three layers of lymphocytes are also observed. The organisms stain well by the GMS method as slightly branched hyphae with an irregular diameter of 7-10 μm, associated with foci of necrosis. Occasionally there is a rounded structure of larger diameter (up to approximately 15 μm) at the end of the hyphae.Lung: there are focal to coalescent areas of consolidation consisting of nodules or sheets of large numbers of epithelioid macrophages and Langhans giant cells admixed with numerous eosinophils and surrounded by fibroblasts and fibrous tissue. The macrophages encircle hyphae similar to that described in the brain that are surrounded by moderate to abundant Splendore-Hoeppli material. Throughout the lung parenchyma there are also small multifocal areas of necrosis containing hyphae. Mineralization is sparsely observed amid necrosis and inflammation. Diffusely, the reminiscent alveolar septa are mildly infiltrated by neutrophils and eosinophils.

Not submitted:

Pyogranulomatous inflammation associated with intralesional hyphae are also observed in the nasal conchae, multifocally in the kidneys and expanding eyelids, sclera and periocular tissues.

In the intestinal lamina propria there are small sparsely distributed foci of mineralization, probably mineralized nodules of Oesophagostomum sp.

The centrilobular hepatocytes have distended cytoplasm by a sizeable solitary vacuole that pushes the nucleus peripherally (centrilobular lipidosis).

The cytoplasm of the cardiomyocytes is expanded by single, oval structures up to 300 μm in length, filled with elongate banana-like organisms (tachyzoites) consistent with protozoal cysts (Sarcocystis sp., most likely S. bovis).

Other sections of the brain, spleen, rumen, omasum, and reticulum have no histopathological changes.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Brain, pyogranulomatous meningoencephalitis, focally extensive, with fibrinoid vasculitis and trombi, associated with intralesional fungal hyphae, morphology consistent with Conidiobolus sp.Lung, pyogranulomatous pneumonia, multifocal to coalescent, associated with intralesional fungal hyphae, morphology consistent with Conidiobolus sp.

Contributor's Comment:

The lesions presented by this ewe are consistent with nasal zygomycosis of sheep which is a common disease in the semiarid Region of Northeastern and Midwestern Brazil.The fungi of Phylum Zygomycota (zygomycetes) that are of importance as cause of animal disease belong to three orders; Mucorales, Mortierellales, and Entomophtorales.19 Zygomycetes include widely distributed saprophytes capable of producing opportunistic diseases in animals, and the term zygomycosis is used to describe the illnesses caused by these fungi. Fungi within the order Entomophtorales (entomophthoromycosis) causing animal diseases include (1) Basidiobolus spp. reported as a cause of cutaneous granulomas in horses,5,15,16 and dogs9,10 and (2) Conidiobolus spp. reported as responsible for granulomatous inflammation in the subcutaneous tissue of horses;12,15 subcutaneous, gastrointestinal and pulmonary granulomas in dogs10 and nasal granulomas in sheep4,13 and horses.12

The term zygomycosis is used to describe the diseases caused by fungi mentioned above. In the past, the term phycomycosis was used to refer to infections induced both by zygomycetes and by the fungus-like organism Pythium insidiosum,5,15,16 now classified as an Oomycete from the kingdom Chromista.19P. insidiosum is a well-known cause of eosinophilic subcutaneous and pulmonary granulomas in horses1,14 and of similar lesions in several other anatomical sites,7,14 including granulomatous rhinitis in sheep21,24 and horses.19

In Brazil, granulomatous rhinitis produced by Conidiobolus spp. is a common affection of sheep with the highest prevalence in the Northeast3,18,20,22,23,27 and Midwest,2,6,26 but also occurring, although less frequently, in the South.8,17 The disease can cause significant losses in sheep due to its high lethality rate, that can reach 100%.2,3

Infection may occur through spore implantation in the nasal cavity by small traumas as insect bites, as was described in C. coronatus infection.11 Inhalation of fungal conidia from the pasture or possibly inoculation by the sharp-pointed plant parts is the presumed means of infection of the nasal cavity. From there, the microorganism invades adjacent tissues by direct dissemination.13,26 The extension of the inflammatory reaction to the orbit causes exophthalmia and other injuries of the eye.1

The invasion of the olfactory bulb and frontal lobe of the brain occurs through destruction of the ethmoid bone by the inflammatory process. This has been reported in relation to the rhinopharyngeal form of Conidiobolus spp. infection2,13,26 with a prevalence of about 20%26 to 40 %.22 In this report the spread also occurred to the lungs, which occurs in this disease in the disease with a prevalence of about 15% of the cases,8,20,26 and probably due to aspiration.26 The strong effort to breathe may cause fragments of the granulomatous mass to detach and lodge in the lungs, developing new granulomatous foci there.22 However, dissemination to distant organs such as the kidney, which is reported here, has probably occurred by lymphatic or hematogenous spread. There is evidence for hematogenous dissemination, including mycotic lesions in the vessel walls and invasion of the lumen of vessels associated with thrombosis.

The fungal or fungal-like produced granulomatous rhinitis in sheep occurs in two forms: (1) rhinofacial presentation that affects the nose and the entrance of the nasal fossae and the upper lip,20,21,26 and (2) rhinopharyngeal presentation that affects the turbinates, paranasal sinuses hard, and soft palates and pharynx.20,22,23,26 Over 85% of cases of rhinofacial presentation are caused by P. insidiosum and over 90% of the cases of rhinopharyngeal presentation are caused by Conidiobolus spp.26 In Brazil, C. lamprauges6,8,26,27 and C. coronatus3,22 have been isolated from these rhinopharyngeal conidiobolomycosis.

Clinical signs consist of serous nasal discharge that evolves to mucous or mucohemorrhagic; the disease is associated with difficult breathing with stridor, anorexia, and swollen of the anterior or posterior nasal cavity.4,13

The tissues of the case reported here were formalin-fixed when they arrived at the laboratory, precluding fungal cultures. Immunohistochemistry and PCR26 would be the best options to confirm the diagnosis. They were not available to us at the time. So, we had to engage in a diagnostic exercise the allowed us to reach etiology with a reasonably good margin of certainty. A comprehensive review of the lesions affecting the nasal cavity of ruminants in Brazil18 listed the following five in small ruminants: rhinopharyngeal conidiobolomycosis, rhinofacial pythiosis, aspergillosis, protothecosis and neoplasia (myxoma and enzootic intranasal tumors). After the histopathological examination, only the first two diseases presented a challenge in the differential diagnosis. However, there are significant clinical and pathological differences between rhinopharyngeal conidiobolomycosis and rhinofacial pythiosis that will allow one to reach a final diagnosis. The clinical sign of exophthalmos, due to the presence of retrobulbar granuloma, is a useful indication of rhinopharyngeal zygomycosis.2,3,4,8,13,17,20,22,26 Although both causal agents may be associated with rhinopharyngeal or rhinofacial presentation of rhinitis in sheep, the location of gross lesions provides a good indicator for the for diagnosis. Disease produced by infection of Conidiobolus spp. are almost always rhinopharyngeal and appear as a firm yellow or white mass; pythiosis, almost always located in the rhinofacial region producing a necrotic and friable cellular exudate. Histologically, important morphological differences between the two diseases include the morphology of the two microorganisms. The hyphae in pythiosis have thick walls, almost parallel, and sparsely septate. The hyphae of Conidiobolus spp. are thin-walled, non-parallel, and sparsely septate, with ballooning dilations in their extremities.

Enzootic intranasal tumors of ruminants are occasionally diagnosed in cattle and sheep in Brazil,18 and rhinopharyngitis caused by Conidiobolus spp. infection has been mistakenly diagnosed as enzootic intranasal tumor. Although these two conditions have some similar aspects, they can be easily differentiated on histological examination.25

Contributing Institution:

Laboratory of Anatomic Pathology, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, https://www.ufms.br/JPC Diagnoses:

- Cerebrum: Meningoencephalitis, pyogranulomatous and necrotizing, chronic, focally extensive, severe, with vasculitis, thrombosis, and numerous intravascular and intrahistiocytic fungal hyphae.

- Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, pyogranulomatous, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with vasculitis and intrahistiocytic fungal hyphae.

JPC Comment:

This is another exceptional write-up by a contributor for this conference. Despite not having ancillary diagnostics available to them, they took on this challenge and presented a clear, concise, and well-organized argument for their diagnosis of Conidiobolus spp. as the causative agent in this case. The pathologist will not always have additional diagnostics at their disposal in real-world situations, so being able to reason through a case, reach a logical conclusion, and present differentials given the case findings is critical to the profession. Additionally, they provided a succinct overview of the pathogenesis of Conidiobolus spp. infections. As far as the case goes, it’s almost as if it read the textbook for lesions while providing a diagnostic challenge to conference-goers.Participants experienced a wide range of emotions during this case presentation due to the difficulty in locating the fungal hyphae on H&E. They are certainly there, but required some squinting to locate and were best found in the sections of cerebrum. Upon revealing the cause, some participants were high-fiving one another out of mutual success while others audibly groaned in dismay.

Discussion focused on indicative features of a zygomycete histologically, which include a broad diameter ranging from 5-15um, non-parallel thin walls, rare septations, asymmetric acute-angle branching, and potentially a terminal bulb. Zygomycetes are typically weakly PAS-positive and more strongly GMS-positive. This correlated nicely with the PAS and GMS stains run in-house. Other differentials mirrored those discussed by the contributor, including oomycetes like Pythium insidiosum, which would be PAS-negative and GMS-positive, as well as Basidiobolus spp., another member of the Entomophthoramycota family alongside Conidiobolus. However, Basidiobolus spp. typically affect the thorax, trunk, limbs, intestinal tract, and, in atypical cases, can cause systemic infection.28Conidiobolus is far more commonly seen localized to face and nostrils. Using a variety of proteases (including elastase and collagenase), lipases, esterases, and glycoside hydrolases at their disposal, Conidiobolus spp. can wreak havoc to the nasal and facial bones and surrounding soft tissues24. Ultimately, they may eat through the cribriform plate and enter the brain.28,29 It’s pretty much “game over” at that point.

References:

- Bianchi MV, Mello LS, De Lorenzo C, et al. Lung lesions of slaughtered horses in southern Brazil. Pesq Vet Bras. 2018;38(11):2056-2064.

- Boabaid FM, Ferreira EV, Arruda LP, et al. Conidiobolomicose em ovinos no Estado de Mato Grosso [Conidiobolomycosis in sheep in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil]. Pesq Vet Bras. 2008;28(1):77-81.

- Câmara ACL, Soto-Blanco B, Batista JS, Vale AM, Feijó FMC, Olinda RG. Rhinocerebral and rhinopharyngeal conidiobolomycosis in sheep. Cienc Rural. 2011;41(5):862-868.

- Carrigan MJ, Small AC, Perry GH. Ovine nasal zygomycosis caused by Conidiobolus incongruous. Aust Vet J. 1992;69(10):237-240.

- Connole MD. Equine phycomycosis. Aust Vet J. 1973;49:215-216.

- de Paula DAJ, Oliveira-Filho JX, Silva MC, et al. Molecular characterization of ovine zygomycosis in central western Brazil. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2010;22:274–277.

- Frade MTS, Diniz PVN, Olinda RG, et al. Pythiosis in dogs in the semiarid region of Northeast Brazil. Pesq Vet Bras. 2017;37(5):485-490.

- Furlan FH, Lucioli J, Veronezi LO, et al. Conidiobolomicose causada por Conidiobolus lamprauges em ovinos no Estado de Santa Catarina [Conidiobolomycosis caused by Conidiobolus lamprauges in sheep in the state of Santa Catarina, Brazil]. Pesq Vet Bras. 2010;30(7):529-532.

- Greene CE, Brockus CW, Currin MP, Jones CJ. Infection by Basidiobolus ranarum in two dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;221:528-532.

- Grooters AM. Pythiosis, lagenidiosis, and zygomicosis in small animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2003;33:695-720.

- Gugnani H. Entomophthoromycosis due to Conidiobolus. Eur J Epidemiol. 1992;8:391-396.

- Humber RA, Brown CC, Kornegay RW. Equine zygomycosis caused by Conidiobolus lamprauges. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:573-576.

- Ketterer PJ, Kelly MA, Connole MD, Ajello L. Rhinocerebral and nasal zygomycosis in sheep caused by Conidiobolus incongruus. Aust Vet J. 1992;69:85-87.

- Martins TB, Kommers GD, Trost ME, Inkelmann MA, Fighera RA, Schild AL. A comparative study of the histopathology and immunohistochemistry of pythiosis in horses, dogs and cattle. J Comp Pathol. 2012;146(2-3):122-131.

- Miller R, Campbell RSF. The comparative pathology of equine cutaneous phycomycosis. Vet Pathol. 1984;21:325-332.

- Miller R, Pott B. Phycomycosis of the horse caused by Basidiobolus haptosporus. Aust Vet J. 1980;56:224-227.

- Pedroso PMO, Dalto AGC, Raymundo DL, et al. Rinite micótica nasofaríngea em um ovino Texel no Rio Grande do Sul [Rhinopharyngeal mycotic rhinitis in a Texel sheep in Rio Grande do Sul]. Acta Sci Vet. 2009;37(2):181-185.

- Portela RA, Riet-Correa F, Garino-Junior F, Dantas AFM, Simões SVD, Silva SMS. Doenças da cavidade nasal em ruminantes no Brasil [Diseases of the nasal cavity of ruminants in Brazil]. Pesq Vet Bras. 2010;30(10):844-854.

- Quinn PJ, Markey BK, Leonard FC, FitzPatrick ES, Fanning S, Hartigan PJ. Zygomycetes of veterinary importance. In: Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Diseases. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell; 2011:466-451.

- Riet-Correa F, Dantas AFM, Azevedo EO, et al. Outbreaks of rhinofacial and rhinopharingeal zygomycosis in sheep in Paraíba, northeastern Brazil. Pesq Vet Bras. 2008;28(1): 29-35.

- Santurio JM, Argenta JS, Schwendler SE, et al. Granulomatous rhinitis associated with Pythium insidiosum infection in sheep. Vet Rec. 2008;163(9):276-277.

- Silva SMMS, Castro RS, Costa FAL, et al. Conidiobolomycosis in sheep in Brazil. Vet Pathol. 2007a;44:314-319.

- Silva SMMS, Castro SC, Costa FAL, et al. Epidemiologia e sinais clínicos da conidiobolomicose em ovinos no Estado do Piauí [Epidemiology and symptoms of conidiobolomycosis in sheep in the State of Piauí, Brazil]. Pesq Vet Bras. 2007b;27(4):184-190.

- Shaikh N, Hussain KA, Petraitiene R, Schuetz AN, Walsh TJ. Entomophthoramycosis: a neglected tropical mycosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(8):688-94.

- Tabosa IM, Riet-Correa F, Nobre VMT, Azevedo EO, Reis-Junior JL, Medeiros RM. Outbreaks of pythiosis in two flocks of sheep in northeastern Brazil. Vet Pathol. 2004;41:412-415.

- Teifke JP, Klopfleisch R, Czerwinski G, et al. Morphologische, immunhistologische und molekulare Untersuchungen zur Pathogenese der enzootischen Nasentumoren beim Schaf. Tierärztl Prax. 2007;35:264-272.

- Ubiali DG, Cruz RAS, de Paula DAJ, et al. Pathology of nasal infection caused by Conidioboulus lamprauges and Pythium insidiosum in sheep. J Comp Pathol. 2013;149:13